An Esthetics of Injury: the Narrative Wound from Baudelaire to Haneke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A QUIET EVENING of DANCE by WILLIAM FORSYTHE Pääyhteistyökumppanit / Partners / Partners Sponsorit / Sponsors / Sponsorer Thu–Fri 22.–23.8

©Bill Cooper #juhlaviikot #helsinkifestival The visit is produced in collaboration with Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation and Dance House Helsinki. A Sadler´s Wells London Production JANE and AATOS ERKKO FOUNDATION A QUIET EVENING OF DANCE BY WILLIAM FORSYTHE Pääyhteistyökumppanit / Partners / Partners Sponsorit / Sponsors / Sponsorer Thu–Fri 22.–23.8. Finnish National Opera and ballet, Almi Hall PRODUCTION CREDITS Dancers: Brigel Gjoka, Jill Johnson, Christopher Roman (understudied by Brit Rodemund in Helsinki), Parvaneh Scharafali, Riley Watts, Rauf “RubberLegz“ Yasit, Ander Zabala Composer/Music: Morton Feldman, Nature Pieces from Piano No.1. From, First Recordings (1950s) – The Turfan Ensemble, Philipp Vandré © Mode (for Epilogue) A Sadler’s Wells London Production Composer/Music: Jean‐Philippe Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie: Ritournelle, from A Quiet Evening of Dance Une Symphonie Imaginaire, Marc Minkowski & Les Musiciens du Louvre © 2005 By William Forsythe Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin (for Seventeen/Twenty One) and Lighting Design: Tanja Rühl and William Forsythe Brigel Gjoka, Jill Johnson, Christopher Roman, Parvaneh Scharafali, Riley Watts, Rauf “RubberLegz” Yasit and Ander Zabala. Costume Design: Dorothee Merg and William Forsythe Co-produced with Théâtre de la Ville, Paris; Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris; Festival d’Automne Sound Design: Niels Lanz à Paris; Festival Montpellier Danse 2019; Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg; The Shed, New York; Onassis Cultural Centre, Athens; deSingel international arts campus, Antwerp. For Sadler’s Wells Artistic Director & Chief Executive: Alistair Spalding CBE First performed at Sadler’s Wells London on 4 October 2018. Executive Producer: Suzanne Walker Head of Producing & Touring: Bia Oliveira Winner of the FEDORA - VAN CLEEF & ARPELS Prize for Ballet 2018. -

Über Gegenwartsliteratur About Contemporary Literature

Leseprobe Über Gegenwartsliteratur Interpretationen und Interventionen Festschrift für Paul Michael Lützeler zum 65. Geburtstag von ehemaligen StudentInnen Herausgegeben von Mark W. Rectanus About Contemporary Literature Interpretations and Interventions A Festschrift for Paul Michael Lützeler on his 65th Birthday from former Students Edited by Mark W. Rectanus AISTHESIS VERLAG ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Bielefeld 2008 Abbildung auf dem Umschlag: Paul Klee: Roter Ballon, 1922, 179. Ölfarbe auf Grundierung auf Nesseltuch auf Karton, 31,7 x 31,1 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. © VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn 2008 Bibliographische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. © Aisthesis Verlag Bielefeld 2008 Postfach 10 04 27, D-33504 Bielefeld Satz: Germano Wallmann, www.geisterwort.de Druck: docupoint GmbH, Magdeburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten ISBN 978-3-89528-679-7 www.aisthesis.de Inhaltsverzeichnis/Table of Contents Danksagung/Acknowledgments ............................................................ 11 Mark W. Rectanus Introduction: About Contemporary Literature ............................... 13 Leslie A. Adelson Experiment Mars: Contemporary German Literature, Imaginative Ethnoscapes, and the New Futurism .......................... 23 Gregory W. Baer Der Film zum Krug: A Filmic Adaptation of Kleist’s Der zerbrochne Krug in the GDR ......................................................... -

Asociación………. Internacional…

ASOCIACIÓN………. INTERNACIONAL… . DE HISPANISTAS… …. ASOCIACIÓN INTERNACIONAL DE HISPANISTAS 16/09 bibliografía publicado en colaboración con FUNDACIÓN DUQUES DE SORIA ©Asociación Internacional de Hispanistas ISBN: 978-88-548-3311-1 Editor: Aurelio González Colaboración: Nashielli Manzanilla y Libertad Paredes Copyright © 2013 ALEMANIA Y AUSTRIA Christoph Strosetzki, Susanne Perrevoort Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster BIBLIOGRAFÍA Acosta Luna, Olga Isabel. Milagrosas imágenes marianas en el Nuevo Reino de Granada. Frankfurt am Main, Vervuert, 2011. 510 pp. Adriaensen, Brigitte y Valeria Grinberg Pla. Narrativas del crimen en América Latina. Transformaciones y transculturaciones del policial. Berlin/Münster, LIT Verlag, 2012. 269 pp. Aguilar y de Córdoba, Diego de. El Marañón. Ed. y est. Julián Díez Torres. Frankfurt am Main, Vervuert, 2011. 421 pp. Aínsa, Fernando. Palabras nómadas. Nueva cartografía de la pertenencia. Frankfurt am Main Vervuert, 2012. 219 pp. Almeida, António de. La verdad escurecida. El hermano fingido. Ed., pról. y not. José Javier Rodríguez Rodríguez. Frankfurt, Main, Vervuert, 2012. 299 pp. Altmann, Werner, Rosamna Pardellas Velay y Ursula Vences (eds.). Historia hispánica. Su presencia y (re) presentación en Alemania. Festschrift für Walther L. Bernecker. Berlin, Tranvia/Verlag Frey, 2012. 252 pp. Álvarez, Marta, Antonio J. Gil González y Marco Kunz (eds.). Metanarrativas hispánicas. Wien/Berlin, LIT Verlag, 2012. 359 pp. Álvarez-Blanco, Palmar y Toni Dorca (coords.). Contornos de la narrativa española actual (2000 - 2010). Un diálogo entre creadores y críticos. Frankfurt am Main, Vervuert, 2011. 318 pp. Annino, Antonio y Marcela Ternavasio (coords.). El laboratorio constitucional Iberoamericano. 1807/1808-1830. Asociación de Historiadores Latinoamericanistas Europeos. Frankfurt am Main, Vervuert, 2012. 264 pp. Arellano, Ignacio y Juan M. -

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples Mittelalter (1150- Wolfram von Eschenbach Epik Parzival (1200/1210) 1450) Gottfried von Straßburg Tristan (ca. 1210) Hartmann von Aue Der arme Heinrich (ca. 1195) Johannes von Tepl Der Ackermann aus Böhmen (ca. 1400) Walther von der Vogelweide Lieder, Oskar von Wolkenstein Minnelyrik, Spruchdichtung Gedichte Renaissance Martin Luther Prosa Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen (1530) (1400-1600) Von der Freyheit eynis Christen Menschen (1521) Historia von D. Johann Fausten (1587) Das Volksbuch vom Eulenspiegel (1515) Der ewige Jude (1602) Sebastian Brant Das Narrenschiff (1494) Barock (1600- H.J.C. von Grimmelshausen Prosa Der abenteuerliche Simplizissimus Teutsch (1669) 1720) Schelmenroman Martin Opitz Lyrik Andreas Gryphius Paul Fleming Sonett Christian v. Hofmannswaldau Paul Gerhard Aufklärung (1720- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Prosa Fabeln 1785) Christian Fürchtegott Gellert Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Drama Nathan der Weise (1779) Bürgerliches Emilia Galotti (1772) Trauerspiel Miss Sara Samson (1755) Lustspiel Minna von Barnhelm oder das Soldatenglück (1767) 2 Sturm und Drang Johann Wolfgang Goethe Prosa Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (1774) (1767-1785) Johann Gottfried Herder Von deutscher Art und Kunst (selections; 1773) Karl Philipp Moritz Anton Reiser (selections; 1785-90) Sophie von Laroche Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim (1771/72) Johann Wolfgang Goethe Drama Götz von Berlichingen (1773) Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz Der Hofmeister oder die Vorteile der Privaterziehung (1774) -

Second Uncorrected Proof ~~~~ Copyright

Into the Groove ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd i ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:57:47 PM Studies in German Literature, Linguistics, and Culture ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd ii ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:58:39 PM Into the Groove Popular Music and Contemporary German Fiction Andrew Wright Hurley Rochester, New York ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd iii ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:58:39 PM This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council. The views expressed herein are those of the author and are not necessarily those of the Australian Research Council. Copyright © 2015 Andrew Wright Hurley All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded, or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First published 2015 by Camden House Camden House is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt. Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA www.camden-house.com and of Boydell & Brewer Limited PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK www.boydellandbrewer.com ISBN-13: 978-1-57113-918-4 ISBN-10: 1-57113-918-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data CIP data applied for. This publication is printed on acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. -

Gunter E. Grimm

GUNTER E. GRIMM Faust-Opern Eine Skizze Vorblatt Publikation Erstpublikation Autor Prof. Dr. Gunter E. Grimm Universität Duisburg-Essen Fachbereich Geisteswissenschaften, Germanistik Lotharstr. 65 47057 Duisburg Emailadresse: [email protected] Homepage: <http://www.uni-duisburg-essen.de/germanistik/mitarbeiterdaten.php?pid=799> Empfohlene Zitierweise Beim Zitieren empfehlen wir hinter den Titel das Datum der Einstellung oder des letzten Updates und nach der URL-Angabe das Datum Ihres letzten Besuchs die- ser Online-Adresse anzugeben: Gunter E. Grimm: Faust Opern. Eine Skizze. In: Goethezeitportal. URL: http://www.goethezeitportal.de/fileadmin/PDF/db/wiss/goethe/faust-musikalisch_grimm.pdf GUNTER E. GRIMM: Faust-Opern. Eine Skizze. S. 2 von 20 Gunter E. Grimm Faust-Opern Eine Skizze Das Faust-Thema stellt ein hervorragendes Beispiel dar, wie ein Stoff, der den dominanten Normen seines Entstehungszeitalters entspricht, bei seiner Wande- rung durch verschiedene Epochen sich den jeweils herrschenden mentalen Para- digmen anpasst. Dabei verändert der ursprüngliche Stoff sowohl seinen Charakter als auch seine Aussage. Schaubild der Faust-Opern Die „Historia von Dr. Faust“ von 1587 entspricht ganz dem christlichen Geist der Epoche. Doktor Faust gilt als Inbegriff eines hybriden Gelehrten, der über das dem Menschen zugestandene Maß an Gelehrsamkeit und Erkenntnis hinausstrebt und zu diesem Zweck einen Pakt mit dem Teufel abschließt. Er wollte, wie es im Volksbuch heißt, „alle Gründ am Himmel vnd Erden erforschen / dann sein Für- GUNTER E. GRIMM: Faust-Opern. Eine Skizze. S. 3 von 20 witz / Freyheit vnd Leichtfertigkeit stache vnnd reitzte jhn also / daß er auff eine zeit etliche zäuberische vocabula / figuras / characteres vnd coniurationes / damit er den Teufel vor sich möchte fordern / ins Werck zusetzen / vnd zu probiern jm fürname.”1 Die „Historia“ mit ihrem schrecklichen Ende stellte eine dezidierte Warnung an diejenigen dar, die sich frevelhaft über die Religion erhoben. -

"With His Blood He Wrote"

:LWK+LV%ORRG+H:URWH )XQFWLRQVRIWKH3DFW0RWLILQ)DXVWLDQ/LWHUDWXUH 2OH-RKDQ+ROJHUQHV Thesis for the degree of philosophiae doctor (PhD) at the University of Bergen 'DWHRIGHIHQFH0D\ © Copyright Ole Johan Holgernes The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Year: 2017 Title: “With his Blood he Wrote”. Functions of the Pact Motif in Faustian Literature. Author: Ole Johan Holgernes Print: AiT Bjerch AS / University of Bergen 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following for their respective roles in the creation of this doctoral dissertation: Professor Anders Kristian Strand, my supervisor, who has guided this study from its initial stages to final product with a combination of encouraging friendliness, uncompromising severity and dedicated thoroughness. Professor Emeritus Frank Baron from the University of Kansas, who encouraged me and engaged in inspiring discussion regarding his own extensive Faustbook research. Eve Rosenhaft and Helga Muellneritsch from the University of Liverpool, who have provided erudite insights on recent theories of materiality of writing, sign and indexicality. Doctor Julian Reidy from the Mann archives in Zürich, with apologies for my criticism of some of his work, for sharing his insights into the overall structure of Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus, and for providing me with some sources that have been valuable to my work. Professor Erik Bjerck Hagen for help with updated Ibsen research, and for organizing the research group “History, Reception, Rhetoric”, which has provided a platform for presentations of works in progress. Professor Lars Sætre for his role in organizing the research school TBLR, for arranging a master class during the final phase of my work, and for friendly words of encouragement. -

EXISTENTIAL CRISIS in FRANZ Kl~Fkl:T

EXISTENTIAL CRISIS IN FRANZ Kl~FKl:t. Thesis submitted to the University ofNor~b ~'!e:n~al for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Ph.Ho§'Ophy. By Miss Rosy Chamling Department of English University of North Bengal Dist. Darjeeling-7340 13 West Bengal 2010 gt)l.IN'tO rroit<. I • NlVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL P.O. NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY, HEAD Raja Rammohunpur, Dist. Da~eeling, DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH West Bengal, India, PIN- 734013. Phone: (0353) 2776 350 Ref No .................................................... Dated .....?.J..~ ..9 . .7.: ... ............. 20. /.~. TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that Miss Rosy Cham!ing has completed her Research Work on •• Existential Crisis in Franz Kafka". As the thesis bears the marks of originality and analytic thinking, I recommend its submission for evaluation . \i~?~] j' {'f- f ~ . I) t' ( r . ~ . s amanta .) u, o:;.?o"" Supervis~r & Head Dept. of English, NBU .. Contents Page No. Preface ......................................................................................... 1-vn Acknowledgements ...................................................................... viii L1st. ot~A'b o -rev1at1ons . ................................................................... 1x. Chapter- I Introduction................................................... 1 1 Chapter- II The Critical Scene ......................................... 32-52 Chapter- HI Authority and the Individual. ........................ 53-110 Chapter- IV Tragic Humanism in Kafka........................... 111-17 5 Chapter- V Realism -

Faust: Ein Bildungsdrama Florian Breitkopf Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2011 Faust: Ein Bildungsdrama Florian Breitkopf Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Breitkopf, Florian, "Faust: Ein Bildungsdrama" (2011). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 460. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/460 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Germanic Languages & Literatures FAUST: EIN BILDUNGSDRAMA DER BILDUNGSDISKURS DER GOETHEZEIT UND SEINE LITERARISCHE REFLEKTION IN JOHANN WOLFGANG GOETHES FAUST by Florian Dominik Breitkopf A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2011 Saint Louis, Missouri copyright by Florian Dominik Breitkopf 2011 Meinem Vater, Helmut Anton Breitkopf. Gliederung 1. Einleitung und Zielsetzung............................................................................................1 2. Der Bildungsbegriff .....................................................................................................10 2.1. Einführung. Das Bildungsprojekt der Goethezeit .................................................10 -

German Culture News Cornell University Institute for German Cultural Studies

GERMAN CULTURE NEWS CORNELL UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE FOR GERMAN CULTURAL STUDIES / (lif _'1/01 , 0/111/1<' \ \" I RETROSPECTIVE OF FROM FRANKFURT TO GERMAN COLLOQUIUM Los ANGELES FALL 2001 AND BACK: DAADSUMMERSEMTNAR On September 7,200I, an enthusiastic crowd assembled for the first Institute AoifeNaughton colloquium ofthe academic year. Pre senting his paper, "Miracles Happen: The opening ofthe Cornell University! Benjamin, Rosenzweig, and the Limits DAAD summerseminar"From Frankfun of the Enlightenment," was Professor to Los Angeles and Back: The Fate of Eric L.Santner, the Harriet and Ulrich Critical Theory in the International De E. Meyer Professor in the Department of bate after World War II" saw an influx of Gennanic Studiesand the Commineeon visiting professors from colleges and Jewish Studies at the UniversityofChi universitiesacross the U,S. and Canada to cago. In his paper, Santner compared Photo by Ifg/lS Meyer-Veden attend the six·week seminar led by Peter Walter Benjamin's understanding of Hohendahl. Thegoal ofthe seminar, which historical material ism asit appears in his PATRIOTISM, ran from June 18 to July 27, 2001, was to "Theses on the Philosophy ofHistory" encourage research by young scholars in to Franz Rosenzweig's reading of the COSMOPOLITANISM, the fieldofcriticaltheory. DAAD fellow "philosophy of creation," proposed ships were awarded to Hester Bat'r(Duke in his The Star of Redemption. AND NATIONAL CULTURE: University), Karyn Ball (University of Rosenzweig's notoriously difficult work HAMBURG CONFERENCE Albena),Sinkwan -

Programmheft Nr

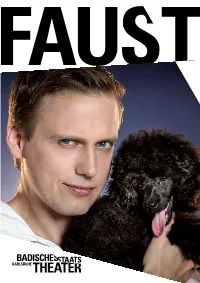

FAUST 1 WERD ICH ZUM AUGENBLICKE SAGEN: VERWEILE DOCH! DU BIST SO SCHON! DANN MAGST DU MICH IN FESSELN SCHLAGEN, DANN WILL ICH GERN ZUGRUNDE GEHN! FAUST Der Tragödie erster Teil von Johann Wolfgang Goethe Faust JANNEK PETRI Mephistopheles HEISAM ABBAS Margarete KIM SCHNITZER Marthe Schwerdtlein LISA SCHLEGEL Valentin LUIS QUINTANA Wagner / Gretchens Mutter SVEN DANIEL BÜHLER Der Herr / Die Hexe / Lieschen MEIK VAN SEVEREN Faust 2-6 / Erdgeist / Bürger / Gesellen in ENSEMBLE Auerbachs Keller / Meerkatzen / Hexen in Walpurgisnacht Regie MICHAEL TALKE Bühne BARBARA STEINER Kostüme INGE MEDERT Musik JOHANNES MITTL Licht CHRISTOPH PÖSCHKO Dramaturgie ROLAND MARZINOWSKI Theaterpädagogik BENEDICT KÖMPF PREMIERE 28.9.17 KLEINES HAUS Aufführungsdauer 2 Stunden, keine Pause Regieassistenz SARAH STEINFELDER Bühnenbildassistenz ANNE HORNY Kostümas- sistenz ADÈLE LAVILLAUROY Soufflage HANS-PETER SCHENCK Inspizienz JULIKA VAN DEN BUSCH Regiehospitanz SANDER LYBEER, PAULINA ROSALIE MÜLLER Bühnenbild- hospitanz LEILA HASSAN POUR ALMANI Technische Direktion HARALD FASSLRINNER, RALF HASLINGER Bühne Kleines Haus HENDRIK BRÜGGEMANN, MORITZ HAUPTVOGEL, EDGAR LUGMAIR Leiter der Be- leuchtungsabteilung STEFAN WOINKE Leiter der Tonabteilung STEFAN RAEBEL Ton JAN FUCHS, DIETER SCHMIDT Leiterin der Requisite MEGAN ROLLER Requisite CLEMENS WIDMANN Werkstättenleiter GUIDO SCHNEITZ Konstrukteur EDUARD MOSER Malsaal- vorstand GIUSEPPE VIVA Leiter der Theaterplastiker LADISLAUS ZABAN Schreinerei ROUVEN BITSCH Schlosserei MARIO WEIMAR Polster- und Dekoabteilung UTE WIEN-