Goethe's Faust II 93 VII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A QUIET EVENING of DANCE by WILLIAM FORSYTHE Pääyhteistyökumppanit / Partners / Partners Sponsorit / Sponsors / Sponsorer Thu–Fri 22.–23.8

©Bill Cooper #juhlaviikot #helsinkifestival The visit is produced in collaboration with Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation and Dance House Helsinki. A Sadler´s Wells London Production JANE and AATOS ERKKO FOUNDATION A QUIET EVENING OF DANCE BY WILLIAM FORSYTHE Pääyhteistyökumppanit / Partners / Partners Sponsorit / Sponsors / Sponsorer Thu–Fri 22.–23.8. Finnish National Opera and ballet, Almi Hall PRODUCTION CREDITS Dancers: Brigel Gjoka, Jill Johnson, Christopher Roman (understudied by Brit Rodemund in Helsinki), Parvaneh Scharafali, Riley Watts, Rauf “RubberLegz“ Yasit, Ander Zabala Composer/Music: Morton Feldman, Nature Pieces from Piano No.1. From, First Recordings (1950s) – The Turfan Ensemble, Philipp Vandré © Mode (for Epilogue) A Sadler’s Wells London Production Composer/Music: Jean‐Philippe Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie: Ritournelle, from A Quiet Evening of Dance Une Symphonie Imaginaire, Marc Minkowski & Les Musiciens du Louvre © 2005 By William Forsythe Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin (for Seventeen/Twenty One) and Lighting Design: Tanja Rühl and William Forsythe Brigel Gjoka, Jill Johnson, Christopher Roman, Parvaneh Scharafali, Riley Watts, Rauf “RubberLegz” Yasit and Ander Zabala. Costume Design: Dorothee Merg and William Forsythe Co-produced with Théâtre de la Ville, Paris; Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris; Festival d’Automne Sound Design: Niels Lanz à Paris; Festival Montpellier Danse 2019; Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg; The Shed, New York; Onassis Cultural Centre, Athens; deSingel international arts campus, Antwerp. For Sadler’s Wells Artistic Director & Chief Executive: Alistair Spalding CBE First performed at Sadler’s Wells London on 4 October 2018. Executive Producer: Suzanne Walker Head of Producing & Touring: Bia Oliveira Winner of the FEDORA - VAN CLEEF & ARPELS Prize for Ballet 2018. -

2020 WWE Finest

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Angel Garza Raw® 2 Akam Raw® 3 Aleister Black Raw® 4 Andrade Raw® 5 Angelo Dawkins Raw® 6 Asuka Raw® 7 Austin Theory Raw® 8 Becky Lynch Raw® 9 Bianca Belair Raw® 10 Bobby Lashley Raw® 11 Murphy Raw® 12 Charlotte Flair Raw® 13 Drew McIntyre Raw® 14 Edge Raw® 15 Erik Raw® 16 Humberto Carrillo Raw® 17 Ivar Raw® 18 Kairi Sane Raw® 19 Kevin Owens Raw® 20 Lana Raw® 21 Liv Morgan Raw® 22 Montez Ford Raw® 23 Nia Jax Raw® 24 R-Truth Raw® 25 Randy Orton Raw® 26 Rezar Raw® 27 Ricochet Raw® 28 Riddick Moss Raw® 29 Ruby Riott Raw® 30 Samoa Joe Raw® 31 Seth Rollins Raw® 32 Shayna Baszler Raw® 33 Zelina Vega Raw® 34 AJ Styles SmackDown® 35 Alexa Bliss SmackDown® 36 Bayley SmackDown® 37 Big E SmackDown® 38 Braun Strowman SmackDown® 39 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown® 40 Carmella SmackDown® 41 Cesaro SmackDown® 42 Daniel Bryan SmackDown® 43 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown® 44 Elias SmackDown® 45 Jeff Hardy SmackDown® 46 Jey Uso SmackDown® 47 Jimmy Uso SmackDown® 48 John Morrison SmackDown® 49 King Corbin SmackDown® 50 Kofi Kingston SmackDown® 51 Lacey Evans SmackDown® 52 Mandy Rose SmackDown® 53 Matt Riddle SmackDown® 54 Mojo Rawley SmackDown® 55 Mustafa Ali Raw® 56 Naomi SmackDown® 57 Nikki Cross SmackDown® 58 Otis SmackDown® 59 Robert Roode Raw® 60 Roman Reigns SmackDown® 61 Sami Zayn SmackDown® 62 Sasha Banks SmackDown® 63 Sheamus SmackDown® 64 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown® 65 Shorty G SmackDown® 66 Sonya Deville SmackDown® 67 Tamina SmackDown® 68 The Miz SmackDown® 69 Tucker SmackDown® 70 Xavier Woods SmackDown® 71 Adam Cole NXT® 72 Bobby -

Albert Schweitzer: a Man Between Two Cultures

, .' UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I LIBRARY ALBERT SCHWEITZER: A MAN BETWEEN TWO CULTURES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES OF • EUROPE AND THE AMERICAS (GERMAN) MAY 2007 By Marie-Therese, Lawen Thesis Committee: Niklaus Schweizer Maryann Overstreet David Stampe We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Languages and Literatures of Europe and the Americas (German). THESIS COMMITIEE --~ \ Ii \ n\.llm~~~il\I~lmll:i~~~10 004226205 ~. , L U::;~F H~' _'\ CB5 .H3 II no. 3Y 35 -- ,. Copyright 2007 by Marie-Therese Lawen 1II "..-. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS T I would like to express my deepest gratitude to a great number of people, without whose assistance, advice, and friendship this thesis w0l!'d not have been completed: Prof. Niklaus Schweizer has been an invaluable mentor and his constant support have contributed to the completion of this work; Prof. Maryann Overstreet made important suggestions about the form of the text and gave constructive criticism; Prof. David Stampe read the manuscript at different stages of its development and provided corrective feedback. 'My sincere gratitude to Prof. Jean-Paul Sorg for the the most interesting • conversations and the warmest welcome each time I visited him in Strasbourg. His advice and encouragement were highly appreciated. Further, I am deeply grateful for the help and advice of all who were of assistance along the way: Miriam Rappolt lent her editorial talents to finalize the text; Lynne Johnson made helpful suggestions about the chapter on Bach; John Holzman suggested beneficial clarifications. -

The Walking Dead,” Which Starts Its Final We Are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Season Sunday on AMC

Las Cruces Transportation August 20 - 26, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Jeffrey Dean Morgan Call us to make is among the stars of a reservation today! “The Walking Dead,” which starts its final We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant season Sunday on AMC. Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more Life for ‘The Walking Dead’ is Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. almost up as Season 11 starts Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section August 20 - 26, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “Movie: We Broke Up” “Movie: The Virtuoso” “Movie: Vacation Friends” “Movie: Four Good Days” From director Jeff Rosenberg (“Hacks,” Anson Mount (“Hell on Wheels”) heads a From director Clay Tarver (“Silicon Glenn Close reunited with her “Albert “Relative Obscurity”) comes this 2021 talented cast in this 2021 actioner that casts Valley”) comes this comedy movie about Nobbs” director Rodrigo Garcia for this comedy about Lori and Doug (Aya Cash, him as a professional assassin who grapples a straight-laced couple who let loose on a 2020 drama that casts her as Deb, a mother “You’re the Worst,” and William Jackson with his conscience and an assortment of week of uninhibited fun and debauchery who must help her addict daughter Molly Harper, “The Good Place”), who break up enemies as he tries to complete his latest after befriending a thrill-seeking couple (Mila Kunis, “Black Swan”) through four days before her sister’s wedding but decide job. -

Download Download

Volume 1, Number 1 (2021) Begriff (Concept) Clark S. Muenzer To cite this article: Muenzer, Clark S. “Begriff (Concept).”Goethe-Lexicon of Philosophical Concepts 1, no. 1 (2021): 20–44. To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.5195/glpc.2021.34 Published by the University Library System, University of Pittsburgh. Entries in this Lexicon are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. Copyright © the Author(s). Begriff (Concept) The lexeme Begriff1 marks Goethe’s ongoing reconstruction of the traditional philosophical concept across a variety of disciplinary practices. In its most developed articulations, it also works transcendentally to establish the conditions of possibility for thought and intelligibility on a dynamic plane of verbal experimentation and reinven- tion that cuts immanently through the world. Unlike the clear and distinct concepts of rationalist metaphysics, which function as fixed universals beyond the reach of the senses, Goethe’s extensive usages and ongoing con- ceptualizations of Begriff draw on an expressive power within language to generate sequences of cognitive moves and moments of transitional understanding that stand in close relation to each other and can be gathered in graded series to be saved for further observation, description, reflection, and reconfiguration. Through its successive lin- guistic manifestations, moreover, and in line with Goethe’s heterodox approach to systematic philosophy, Begriff lays out force fields of verbal and philosophical activity and discovery with fluid and permeable borders. In ways comparable to the power of reflective judgment in Kant’s third critique, which dispenses with the categories of the understanding and their determining judgments to work intuitively within the world of living forms (Gestalten), Goethe’s lebendiger Begriff (living concept) proves to be a more encompassing structure of thought and its process- es than the conceptual machinery of orthodox metaphysical systems with their regulatory regimes of limit-setting terms. -

Gunter E. Grimm

GUNTER E. GRIMM Faust-Opern Eine Skizze Vorblatt Publikation Erstpublikation Autor Prof. Dr. Gunter E. Grimm Universität Duisburg-Essen Fachbereich Geisteswissenschaften, Germanistik Lotharstr. 65 47057 Duisburg Emailadresse: [email protected] Homepage: <http://www.uni-duisburg-essen.de/germanistik/mitarbeiterdaten.php?pid=799> Empfohlene Zitierweise Beim Zitieren empfehlen wir hinter den Titel das Datum der Einstellung oder des letzten Updates und nach der URL-Angabe das Datum Ihres letzten Besuchs die- ser Online-Adresse anzugeben: Gunter E. Grimm: Faust Opern. Eine Skizze. In: Goethezeitportal. URL: http://www.goethezeitportal.de/fileadmin/PDF/db/wiss/goethe/faust-musikalisch_grimm.pdf GUNTER E. GRIMM: Faust-Opern. Eine Skizze. S. 2 von 20 Gunter E. Grimm Faust-Opern Eine Skizze Das Faust-Thema stellt ein hervorragendes Beispiel dar, wie ein Stoff, der den dominanten Normen seines Entstehungszeitalters entspricht, bei seiner Wande- rung durch verschiedene Epochen sich den jeweils herrschenden mentalen Para- digmen anpasst. Dabei verändert der ursprüngliche Stoff sowohl seinen Charakter als auch seine Aussage. Schaubild der Faust-Opern Die „Historia von Dr. Faust“ von 1587 entspricht ganz dem christlichen Geist der Epoche. Doktor Faust gilt als Inbegriff eines hybriden Gelehrten, der über das dem Menschen zugestandene Maß an Gelehrsamkeit und Erkenntnis hinausstrebt und zu diesem Zweck einen Pakt mit dem Teufel abschließt. Er wollte, wie es im Volksbuch heißt, „alle Gründ am Himmel vnd Erden erforschen / dann sein Für- GUNTER E. GRIMM: Faust-Opern. Eine Skizze. S. 3 von 20 witz / Freyheit vnd Leichtfertigkeit stache vnnd reitzte jhn also / daß er auff eine zeit etliche zäuberische vocabula / figuras / characteres vnd coniurationes / damit er den Teufel vor sich möchte fordern / ins Werck zusetzen / vnd zu probiern jm fürname.”1 Die „Historia“ mit ihrem schrecklichen Ende stellte eine dezidierte Warnung an diejenigen dar, die sich frevelhaft über die Religion erhoben. -

"With His Blood He Wrote"

:LWK+LV%ORRG+H:URWH )XQFWLRQVRIWKH3DFW0RWLILQ)DXVWLDQ/LWHUDWXUH 2OH-RKDQ+ROJHUQHV Thesis for the degree of philosophiae doctor (PhD) at the University of Bergen 'DWHRIGHIHQFH0D\ © Copyright Ole Johan Holgernes The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Year: 2017 Title: “With his Blood he Wrote”. Functions of the Pact Motif in Faustian Literature. Author: Ole Johan Holgernes Print: AiT Bjerch AS / University of Bergen 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following for their respective roles in the creation of this doctoral dissertation: Professor Anders Kristian Strand, my supervisor, who has guided this study from its initial stages to final product with a combination of encouraging friendliness, uncompromising severity and dedicated thoroughness. Professor Emeritus Frank Baron from the University of Kansas, who encouraged me and engaged in inspiring discussion regarding his own extensive Faustbook research. Eve Rosenhaft and Helga Muellneritsch from the University of Liverpool, who have provided erudite insights on recent theories of materiality of writing, sign and indexicality. Doctor Julian Reidy from the Mann archives in Zürich, with apologies for my criticism of some of his work, for sharing his insights into the overall structure of Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus, and for providing me with some sources that have been valuable to my work. Professor Erik Bjerck Hagen for help with updated Ibsen research, and for organizing the research group “History, Reception, Rhetoric”, which has provided a platform for presentations of works in progress. Professor Lars Sætre for his role in organizing the research school TBLR, for arranging a master class during the final phase of my work, and for friendly words of encouragement. -

Faust: Ein Bildungsdrama Florian Breitkopf Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2011 Faust: Ein Bildungsdrama Florian Breitkopf Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Breitkopf, Florian, "Faust: Ein Bildungsdrama" (2011). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 460. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/460 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Germanic Languages & Literatures FAUST: EIN BILDUNGSDRAMA DER BILDUNGSDISKURS DER GOETHEZEIT UND SEINE LITERARISCHE REFLEKTION IN JOHANN WOLFGANG GOETHES FAUST by Florian Dominik Breitkopf A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2011 Saint Louis, Missouri copyright by Florian Dominik Breitkopf 2011 Meinem Vater, Helmut Anton Breitkopf. Gliederung 1. Einleitung und Zielsetzung............................................................................................1 2. Der Bildungsbegriff .....................................................................................................10 2.1. Einführung. Das Bildungsprojekt der Goethezeit .................................................10 -

Vom Himmel Durch Die Welt Zur Hölle-Bd-30 TEIL

JAHRBUCH DER PSYCHOANALYSE Beiträge zur Theorie und Praxis Unter Mitwirkung von K. R. Eissler, New York - P. Kuiper, Amsterdam E. Laufer, London - K. A. Menninger, Topeka (Kansas) P. Parin , Zürich - W. Solms, Wien L. Wurmser, Towson (Maryland) Herausgegeben von Friedrich-Wilhelm Eickhoff, Tübingen - Wolfgang Loch, Rottweil Schriftleitung und Hermann Beland, Berlin - Edeltrud Meistermann-Seeger, Köln Horst-Eberhard Richter, Gießen - Gerhart Scheunert, Bad Kissingen Band 30 frommann-holzboog „Vom Himmel durch die Welt zur Hölle“ * Zur Goethe-Preisverleihung an Sigmund Freud im Jahre 1930 1 Tomas Plänkers Als Freud vor 6i jähren am 28. August 1930 feierlich den Goethe-Preis der Stadt Frankfurt verliehen bekam, erlaubte es der Gesundheitszustand des 74jährigen nicht, daß er selber den Preis entgegennahm. Durch seine Tochter Anna Freud ließ er eine Dankesrede verlesen, in der er der Beziehung der Psychoanalyse zum Werk Goethes nachging und sich auch mit der Kritik auseinandersetzte, die in dem Versuch einer psychoanalytischen Betrachtung Goethes bereits eine Erniedrigung des Dichters sah. Freud hielt den anwesenden politischen und intellektuellen Honoratioren der Stadt Frankfurt vor: „Unsere Einstellung zu Vätern und Lehrern ist nun einmal eine ambivalente, denn unsere Verehrung für sie deckt regelmäßig eine Komponente feindseliger Auflehnung". Diese auf Goethe hin gesprochenen Worte, ließen sich für den, der es hören wollte, auch mühelos auf den Goethe-Preisträger selber beziehen, denn der Feier im Goethe-Haus ging eine ungewöhnlich kontroverse Diskussion um Freud im Preiskuratorium voraus, welche zwar eine Mehrheit für Freud ergab, aber die Polarisierung der Meinungen keineswegs aufheben konnte. Be- * Schlußzeile des „Vorspiels auf dem Theater" in Goethes Faust. Freud schlug diese Zeile im Brief vom 3.1.1897 an Fließ als Motto einer geplanten Arbeit über „Sexualität" vor; in den „Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie" (1905d, S. -

Programmheft Nr

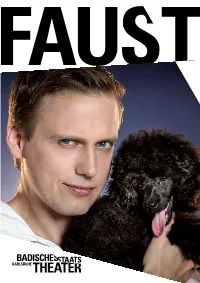

FAUST 1 WERD ICH ZUM AUGENBLICKE SAGEN: VERWEILE DOCH! DU BIST SO SCHON! DANN MAGST DU MICH IN FESSELN SCHLAGEN, DANN WILL ICH GERN ZUGRUNDE GEHN! FAUST Der Tragödie erster Teil von Johann Wolfgang Goethe Faust JANNEK PETRI Mephistopheles HEISAM ABBAS Margarete KIM SCHNITZER Marthe Schwerdtlein LISA SCHLEGEL Valentin LUIS QUINTANA Wagner / Gretchens Mutter SVEN DANIEL BÜHLER Der Herr / Die Hexe / Lieschen MEIK VAN SEVEREN Faust 2-6 / Erdgeist / Bürger / Gesellen in ENSEMBLE Auerbachs Keller / Meerkatzen / Hexen in Walpurgisnacht Regie MICHAEL TALKE Bühne BARBARA STEINER Kostüme INGE MEDERT Musik JOHANNES MITTL Licht CHRISTOPH PÖSCHKO Dramaturgie ROLAND MARZINOWSKI Theaterpädagogik BENEDICT KÖMPF PREMIERE 28.9.17 KLEINES HAUS Aufführungsdauer 2 Stunden, keine Pause Regieassistenz SARAH STEINFELDER Bühnenbildassistenz ANNE HORNY Kostümas- sistenz ADÈLE LAVILLAUROY Soufflage HANS-PETER SCHENCK Inspizienz JULIKA VAN DEN BUSCH Regiehospitanz SANDER LYBEER, PAULINA ROSALIE MÜLLER Bühnenbild- hospitanz LEILA HASSAN POUR ALMANI Technische Direktion HARALD FASSLRINNER, RALF HASLINGER Bühne Kleines Haus HENDRIK BRÜGGEMANN, MORITZ HAUPTVOGEL, EDGAR LUGMAIR Leiter der Be- leuchtungsabteilung STEFAN WOINKE Leiter der Tonabteilung STEFAN RAEBEL Ton JAN FUCHS, DIETER SCHMIDT Leiterin der Requisite MEGAN ROLLER Requisite CLEMENS WIDMANN Werkstättenleiter GUIDO SCHNEITZ Konstrukteur EDUARD MOSER Malsaal- vorstand GIUSEPPE VIVA Leiter der Theaterplastiker LADISLAUS ZABAN Schreinerei ROUVEN BITSCH Schlosserei MARIO WEIMAR Polster- und Dekoabteilung UTE WIEN- -

Goethean Science to See the World Differently, in Its Entirety

Goethean Science to See the start somewhere. Immersing ourselves in nature and in art and doing deep organic World Differently, in its agriculture brings us back to the path and Entirety be at one with nature. We all have that innate longing to know the world. To date, we have been seeing the world predominantly through one reductionist way, and this has diminished our connection to the whole. One of the dimensions articulated in Sustainable Agriculture is holistic, integrative science. But do we have the means to achieve this given our current training in thinking and learning, our mental framework, and our educational background? Einstein said that… “We can't solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” So we need a different kind of science to approach scientific inquiry; not the one or from the program that created chemical based, monocropping type agriculture. Let us see how Goethean Science may be of help. An excerpt of the following articles will give us a glimpse of what it is… Then we see that the mainstream way to science or of knowing the world is a far cry from that which would lead us to the greater and deep truth. It will be a long way to reach the reform that we dream of, but we can *** 1. Goethean Science. http://www.kheper.net/metamorphosis/Goethean.html Goethean science is an approach to knowing the world, that serves as an intuitive or "right brain" (so to speak) complement to the traditional rationalistic "left brain" science… As the name suggests, it was founded by the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), who was in turn influenced by earlier philosophers like Spinoza and Leibniz. -

November 23, 2015 Wrestling Observer Newsletter

1RYHPEHU:UHVWOLQJ2EVHUYHU1HZVOHWWHU+ROPGHIHDWV5RXVH\1LFN%RFNZLQNHOSDVVHVDZD\PRUH_:UHVWOLQJ2EVHUYHU)LJXUH)RXU2« RADIO ARCHIVE NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE THE BOARD NEWS NOVEMBER 23, 2015 WRESTLING OBSERVER NEWSLETTER: HOLM DEFEATS ROUSEY, NICK BOCKWINKEL PASSES AWAY, MORE BY OBSERVER STAFF | [email protected] | @WONF4W TWITTER FACEBOOK GOOGLE+ Wrestling Observer Newsletter PO Box 1228, Campbell, CA 95009-1228 ISSN10839593 November 23, 2015 UFC 193 PPV POLL RESULTS Thumbs up 149 (78.0%) Thumbs down 7 (03.7%) In the middle 35 (18.3%) BEST MATCH POLL Holly Holm vs. Ronda Rousey 131 Robert Whittaker vs. Urijah Hall 26 Jake Matthews vs. Akbarh Arreola 11 WORST MATCH POLL Jared Rosholt vs. Stefan Struve 137 Based on phone calls and e-mail to the Observer as of Tuesday, 11/17. The myth of the unbeatable fighter is just that, a myth. In what will go down as the single most memorable UFC fight in history, Ronda Rousey was not only defeated, but systematically destroyed by a fighter and a coaching staff that had spent years preparing for that night. On 2/28, Holly Holm and Ronda Rousey were the two co-headliners on a show at the Staples Center in Los Angeles. The idea was that Holm, a former world boxing champion, would impressively knock out Raquel Pennington, a .500 level fighter who was known for exchanging blows and not taking her down. Rousey was there to face Cat Zingano, a fight that was supposed to be the hardest one of her career. Holm looked unimpressive, barely squeaking by in a split decision. Rousey beat Zingano with an armbar in 14 seconds.