Economic Analysis of Feral Goat Control Within the NSW Rangeland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Prospectus

Cobar Shire Cobar Shire is located in western New South Wales, about 700 kilometres north-west of Sydney and 650 kilometres north of Canberra. Cobar is on the crossroads of three major highways – the Kidman Way linking Melbourne to Brisbane, the Barrier Highway linking Sydney to Adelaide via Broken Hill and the Wool Track linking the Sunraysia area to Queensland. Cobar Shire is home to around 5,000 people, the majority of whom live in the town of Cobar. The Shire is also made up of grazing leases and villages, with small villages at Euabalong, Euabalong West, Mount Hope and Nymagee. The Shire encompasses a total land area of about 46,000 square kilometres. The Shire's prosperity is built around the thriving mining - copper, lead, silver, zinc, gold - and pastoral industries, which are strongly supported by a wide range of attractions and activities, that attract around 120,000 visitors to the Shire a year. Rail and air infrastructure include regular freight trains to Sydney, a recently upgraded airport, a daily bus service to Dubbo and Broken Hill and freight and courier options available for all goods and services. Cobar boasts a strong and reliable workforce which has a wide range of skills, particularly in mining, manufacturing and supporting industries, trades, retail and agriculture. A good supply of general labour is available to meet the needs of new and expanding businesses. There is ample land available for development, both serviced and un-serviced. There is a wide variety of housing in Cobar, including town blocks of varying size and zoning, rural residential blocks and rural holdings. -

Outback NSW Regional

TO QUILPIE 485km, A THARGOMINDAH 289km B C D E TO CUNNAMULLA 136km F TO CUNNAMULLA 75km G H I J TO ST GEORGE 44km K Source: © DEPARTMENT OF LANDS Nindigully PANORAMA AVENUE BATHURST 2795 29º00'S Olive Downs 141º00'E 142º00'E www.lands.nsw.gov.au 143º00'E 144º00'E 145º00'E 146º00'E 147º00'E 148º00'E 149º00'E 85 Campground MITCHELL Cameron 61 © Copyright LANDS & Cartoscope Pty Ltd Corner CURRAWINYA Bungunya NAT PK Talwood Dog Fence Dirranbandi (locality) STURT NAT PK Dunwinnie (locality) 0 20 40 60 Boonangar Hungerford Daymar Crossing 405km BRISBANE Kilometres Thallon 75 New QUEENSLAND TO 48km, GOONDIWINDI 80 (locality) 1 Waka England Barringun CULGOA Kunopia 1 Region (locality) FLOODPLAIN 66 NAT PK Boomi Index to adjoining Map Jobs Gate Lake 44 Cartoscope maps Dead Horse 38 Hebel Bokhara Gully Campground CULGOA 19 Tibooburra NAT PK Caloona (locality) 74 Outback Mungindi Dolgelly Mount Wood NSW Map Dubbo River Goodooga Angledool (locality) Bore CORNER 54 Campground Neeworra LEDKNAPPER 40 COUNTRY Region NEW SOUTH WALES (locality) Enngonia NAT RES Weilmoringle STORE Riverina Map 96 Bengerang Check at store for River 122 supply of fuel Region Garah 106 Mungunyah Gundabloui Map (locality) Crossing 44 Milparinka (locality) Fordetail VISIT HISTORIC see Map 11 elec 181 Wanaaring Lednapper Moppin MILPARINKA Lightning Ridge (locality) 79 Crossing Coocoran 103km (locality) 74 Lake 7 Lightning Ridge 30º00'S 76 (locality) Ashley 97 Bore Bath Collymongle 133 TO GOONDIWINDI Birrie (locality) 2 Collerina NARRAN Collarenebri Bullarah 2 (locality) LAKE 36 NOCOLECHE (locality) Salt 71 NAT RES 9 150º00'E NAT RES Pokataroo 38 Lake GWYDIR HWY Grave of 52 MOREE Eliza Kennedy Unsealed roads on 194 (locality) Cumborah 61 Poison Gate Telleraga this map can be difficult (locality) 120km Pincally in wet conditions HWY 82 46 Merrywinebone Swamp 29 Largest Grain (locality) Hollow TO INVERELL 37 98 For detail Silo in Sth. -

Bioregions of NSW: Cobar Peneplain

105 CHAPTER 9 The Cobar Peneplain Bioregion Cobar Cobar Peneplain 1. Location the Barwon, Macquarie, Yanda, Darling, Lachlan and Murrumbidgee catchments. The Cobar Peneplain Bioregion lies in central NSW west of the Great Dividing Range. It is one of only two of the state’s bioregions to occur entirely within the state, the other being the Sydney Basin Bioregion. The bioregion extends 2. Climate from just south of Bourke to north of Griffith, has a total area of 7,334,664 ha, The Cobar Peneplain is one of 6 bioregions that lie in Australia’s hot, and occupies 9.2% of the state. The bioregion is bounded to the north and persistently dry semi-arid climatic zone. This climate is complemented by east by the Darling Riverine Plains Bioregion, to the east by the South Western patches of sub-humid climate on the southeastern boundary of the Slopes Bioregion, and by the Riverina and Murray Darling Depression bioregion and, in the south, these areas are characterised by virtually no dry Bioregions to the south and west. The northwestern part of the Cobar season and a hot summer (Stern et al. 2000). Peneplain Bioregion falls in the Western Division. Throughout the year, average evaporation exceeds the average rainfall. The Cobar Peneplain Bioregion encompasses the townships of Cobar, Rainfall tends to be summer dominant in the north of the bioregion and Nymagee, Byrock, Girilambone, Lake Cargelligo and Rankins Springs with winter dominant in the south (Creaser and Knight 1996, Smart et al. 2000a). Louth and Tottenham lying at its boundary. Temperatures are typically mild in winter and hot in summer and exceed 40°C In the north of the bioregion, Yanda Creek, a major stream, discharges directly for short periods during December to February (Creaser and Knight 1996). -

Cobar Shire Council

All communicotions to be addressed Cobor Shire Council Offices: to the General Manager 36 Linsley Street P.O. Box 223 Cobar NSW 2835 Cobor NSW 2835 ABN 71 579 717 155 Telephone: (02) 6836 5888 Shsr~ Facsimile: (02) 6836 5889 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cobar.nsw.gov.au EMP Inquiry In your reply please quote: Submission No. 15 Reference: E5-1/13946 “Regional Centre in Western NSW” KER:NFH th Tuesday 29 July 2003 The Secretary Standing Committee on Employment and Workplace Relations House ofRepresentatives Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Sir/Madam Subject: SUBMISSION — INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN PAID EMPLOYMENT Please find attached Council’s submission in relation to the House ofRepresentatives enquiryinto increasing participation in paid employment. Yours faithfully K.E. Roberts HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGER Attach.... HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEE ON EMPLOYMENT AND WORKPLACE RELATIONS lAUG 2003 RECEIVED Cohar - On the crossroads of the Kidman Way and the Barrier Highway COBAR SHIRE COUNCIL SUBMISSION — INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN PAID EMPLOYMENT Cobar Shire Council is a rural, local government authority located in far west NSW, approximately 295 kilometres west ofDubbo and 711 kilometres west ofSydney. The Council serves an area of some 44,065 square kilometres with a population of approximately 7,500. Cobar Shire Council believes that ‘measures’ can be implemented to increase the level of participation in paid employment, in the form of labour market flexibility, employer and employee assistance/incentives. As a local government authority, and one of four major employers in the shire, Cobar Shire Council has always found it increasingly difficult to attract and retain qualified staff due to the following: 1. -

SAG Reel 357 0357

JOINT COPY PROJECT Uniting Church Archives of NSW & ACT Marriage Registers of the Presbyterian Church Society of Australian Genealogists – Sydney National Library of Australia - Canberra Mitchell Library – Sydney SAG Reel 357 0357 PLACE includes - OTHER START DATE END DATE Register PLACES References Narrandera Whitton; Darlington 3 March 1908 13 January 1914 120 1 Point; Gillenbah; Leeton; [dates differ to title page sheet] Narrandera Corobimilla; Grong 25 March 1924 10 April 1929 120 2 Grong; Narrandera 20 April 1929 31 March 1934 120 3 Narrandera Mount Crystal; Grong 3 April 1934 1 September 1937 120 5 Grong; Corobimilla; Narrandera Grong Grong; Wagga 8 September 1937 10 March 1945 120 5 Wagga; Leeton; Narrandera Leeton; Grong Grong; 10 October 1945 25 February 1950 120 6 Methodist Ganmain; Narrandera Grong Grong; Boree 3 March 1950 16 April 1958 120 7 Creek; Urana; Narrandera 19 April 1958 19 December 1959 120 8 Narromine Timbrebongie; 1 June 1910 14 December 1911 121 1 Narromine Lockhart; Manilla; 20 July 1912 5 January 1916 121 2 Narromine Wyanga; Nyngan; 21 January 1913 7 January 1914 121 3 Trangie; Burwood; Warren; Dandaloo; Narromine 15 July 1918 28 March 1923 121 5 Narromine Peak Hill Methodist; 11 August 1944 13 April 1954 121 2 Narromine, Trangie Condobolin; Dubbo; Scots 15 March 1955 17 October 1959 121 4 College Chapel‐Sydney; The original records are held by Uniting Church Archives of NSW/ACT at North Parramatta and permission was granted for their microfilming to be undertaken by W & F Pascoe Pty Ltd in 2009. This microfilm is supplied for information and research purposes only. -

Table of Contents

Biolink koala conservation review Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 6 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE NSW POPULATION .............................................................. 6 Current distribution ................................................................................................... 6 Size of NSW koala population .................................................................................... 8 4. INFORMING CHANGES TO POPULATION ESTIMATES .......................................... 12 Bionet Records and Published Reports .................................................................... 15 Methods – Bionet records ................................................................................... 15 Methods – available reports ................................................................................ 15 Results .................................................................................................................. 16 The 2019 Fires .......................................................................................................... 22 Methods ............................................................................................................... 22 Results .................................................................................................................. 23 Data Deficient -

Your Complete Guide to Broken Hill and The

YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO DESTINATION BROKEN HILL Mundi Mundi Plains Broken Hill 2 City Map 4–7 Getting There and Around 8 HistoriC Lustre 10 Explore & Discover 14 Take a Walk... 20 Arts & Culture 28 Eat & Drink 36 Silverton Places to Stay 42 Shopping 48 Silverton prospects 50 Corner Country 54 The Outback & National Parks 58 Touring RoutEs 66 Regional Map 80 Broken Hill is on Australian Living Desert State Park Central Standard Time so make Line of Lode Miners Memorial sure you adjust your clocks to suit. « Have a safe and happy journey! Your feedback about this guide is encouraged. Every endeavour has been made to ensure that the details appearing in this publication are correct at the time of printing, but we can accept no responsibility for inaccuracies. Photography has been provided by Broken Hill City Council, Destination NSW, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, Simon Bayliss, The Nomad Company, Silverton Photography Gallery and other contributors. This visitor guide has been designed by Gang Gang Graphics and produced by Pace Advertising Pty. Ltd. ABN 44 005 361 768 Tel 03 5273 4777 W pace.com.au E [email protected] Copyright 2020 Destination Broken Hill. 1 Looking out from the Line Declared Australia’s first heritage-listed of Lode Miners Memorial city in 2015, its physical and natural charm is compelling, but you’ll soon discover what the locals have always known – that Broken Hill’s greatest asset is its people. Its isolation in a breathtakingly spectacular, rugged and harsh terrain means people who live here are resilient and have a robust sense of community – they embrace life, are self-sufficient and make things happen, but Broken Hill’s unique they’ve always got time for each other and if you’re from Welcome to out of town, it doesn’t take long to be embraced in the blend of Aboriginal and city’s characteristic old-world hospitality. -

Cobar Library Local History List.Xlsx

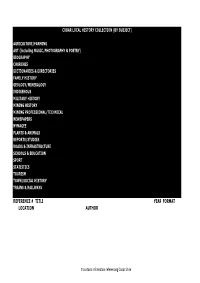

COBAR LOCAL HISTORY COLLECTION (BY SUBJECT) AGRICULTURE/FARMING ART (including MUSIC, PHOTOGRAPHY & POETRY) BIOGRAPHY CHURCHES DICTIONARIES & DIRECTORIES FAMILY HISTORY GEOLOGY/MINERALOGY INDIGENOUS MILITARY HISTORY MINING HISTORY MINING PROFESSIONAL/TECHNICAL NEWSPAPERS NYMAGEE PLANTS & ANIMALS REPORTS/STUDIES ROADS & INFRASTRUCTURE SCHOOLS & EDUCATION SPORT STATISTICS TOURISM TOWN/SOCIAL HISTORY TRAINS & RAILWAYS REFERENCE # TITLE YEAR FORMAT LOCATION AUTHOR # contains information referencing Cobar Shire AGRICULTURE/FARMING # contains information referencing Cobar Shire 264634 Forests, fleece & prickly pears # 1997 Paperback LOCAL HISTORY/508.94/KRU Karl Kruszelnicki 242345 Atlas of New South Wales pastoral stations : a guide to the property names of the larger holdings in NSW and the ACT LOCAL HISTORY/630.0994/ALI Terrance Alick 2004 Paperback 264675 100 years : celebrating 100 years of natural resource progress in the Western Division of NSW # LOCAL HISTORY/994.49/BAR Maree Barnes & Geoff Wise 2003 Paperback Originally published by West 2000 Plus : Western people looking after the Western Division and NSW Department of Sustainable Natural Resouces Reprinted in 2010 by the Western Cathment Management Authority A collection of images, history and stories from the Western Division of New South Wales 237005 Gunderbooka : a 'stone country' story # 2000 Paperback LOCAL HISTORY/994.49/MAI George Main A story of how the landscape of far-western NSW imposed itself upon people and shaped them Starting with the first Aborigines the cycle moves through the pastoralists and back to indigenous ownership 264724 Western lands # 1990 Paperback LOCAL HISTORY/994.49/WES Published by the Western Lands Commission, Department of Lands A booklet providing information on land administration in the Western Division, including facts on the region's history, economy and natural resources ART (including MUSIC, PHOTOGRAPHY & POETRY) # contains information referencing Cobar Shire 264682 Annual report 2016 # 2016 A5 booklet LOCAL HISTORY/709/OUT Outback Arts 264683 Artbark. -

Grey Box (Eucalyptus Microcarpa) Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of South-Eastern Australia

Grey Box (Eucalyptus microcarpa) Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of South-Eastern Australia: A guide to the identification, assessment and management of a nationally threatened ecological community Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 Glossary the Glossary at the back of this publication. © Commonwealth of Australia 2012 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercialised use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Public Affairs - Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2610 Australia or email [email protected] Disclaimer The contents of this document have been compiled using a range of source materials and is valid as at June 2012. The Australian Government is not liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of the document. CONTENTS WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THIS GUIDE? 1 NATIONALLY THREATENED ECOLOGICAL COMMUNITIES 2 What is a nationally threatened ecological community? 2 Why does the Australian Government list threatened ecological communities? 2 Why list the Grey Box (Eucalyptus microcarpa) Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of South-Eastern Australia as -

1 May 2020 Works Report AP Review

NARROMINE SHIRE COUNCIL ORDINARY MEETING BUSINESS PAPER – 6 MAY 2020 REPORTS TO COUNCIL – INFRASTRUCTURE AND ENGINEERING SERVICES 1. WORKS REPORT Author Director Infrastructure and Engineering Services Responsible Officer Director Infrastructure and Engineering Services Link to Strategic Plans CSP – 4.3.4 Ensure Council’s property assets are monitored and well managed Executive Summary This report provides information regarding works undertaken for the given period in regards to both operational and capital works. Report The Works Report (Attachment No. 1) for the period 4 April 2020 to 29 April 2020 is presented to Council for information. Financial Implications Council has provision for these services in its 19/20 Operational Budget. Legal and Regulatory Compliance Local Government Act 1993 Roads Act 1993 Risk Management Issues Nil Internal/External Consultation Nil Attachments 1. Works Report RECOMMENDATION That the information be noted. André Pretorius Director Infrastructure and Engineering Services Page No 1 Attachment No. 1 MONTHLY WORKS REPORT Infrastructure and Engineering Services Narromine Shire Council Tel: 02 6889 9999 Wednesday, 30 April 2020 Fax: 02 6889 9998 [email protected] Road and Park users are to proceed with caution at all work sites and observe work signs to ensure safety. Speed zones are enforceable with possible short delays. For all enquiries, please contact Council’s Infrastructure and Engineering Services Department on 6889 9999. URBAN ROADS – Narromine, Trangie, Tomingley Maintenance: Various Streets (Narromine) Routine Maintenance Program such as patching and street sweeping, etc. Maintenance: Various Streets (Trangie) Routine Maintenance Program such as patching and street sweeping, etc. Maintenance: Various Streets (Tomingley) Routine Maintenance Program. -

Mitchell Cluster

THE CENTRE Australia’sOF NSW Wool & Cotton Capital A History of Bourke...................................................................................3 A History of Brewarrina...........................................................................5 A History of Cobar .....................................................................................6 A History of Narromine ............................................................................7 A History of Nyngan..................................................................................9 A History of Tottenham .........................................................................10 A History of Trangie................................................................................11 A History of Tullamore...........................................................................12 A History of Wanaaring..........................................................................13 A History of Warren.................................................................................14 Things you need to know ......................................................................15 Things you need to know ......................................................................15 All that The Centre of NSW has to Offer ..........................................18 Cultural Services..........................................................................................18 Communications..........................................................................................20 -

Farming Systems in the Pastoral Zone of NSW: an Economic Analysis

Farming Systems in the Pastoral Zone of NSW: An Economic Analysis Salahadin A. Khairo John D. Mullen Ronald B. Hacker Dean A. Patton Economic Research Report No. 31 Farming Systems in the Pastoral Zone of NSW: An Economic Analysis Salahadin Khairo Economist, Pastures and Rangelands NSW DPI, Trangie John Mullen Research Leader, Economics Research NSW DPI, Orange Ron Hacker Research Leader, Pastures and Rangelands NSW DPI, Trangie Dean Patton Manager Condobolin Agricultural Research Centre March 2008 Economic Research Report No. 31 ii © NSW DPI 2008 This publication is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process, electronic or otherwise, without the specific written permission of the copyright owner. Neither may information be stored electronically in any way whatever without such permission. ABSTRACT A ‘broad brush’ picture of farming in the pastoral zone of NSW is presented in this report. The pastoral zone of NSW is characterised by wide variations in climatic conditions, soil type and vegetation species. Hence representative faming system analysis was conducted for three sub-regions - the Upper Darling, the Murray-Darling and Far West. The regions were defined and described in terms of their resources, climate and the nature of agriculture. The main enterprises that farmers choose between were described and whole farm budgets and statements of assets and liabilities for the representative farms were developed. The representative farm models were used to compare traditional Merino based sheep enterprises with alternative sheep enterprises where meat was an important source of income. We found that the farming systems that have evolved in these areas are well suited to their respective environments and that the economic incentives to switch to more meat focussed sheep enterprises were not strong.