Going in the Right Direction? Careers Guidance in Schools from September 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(SIAMS) Report

Statutory Inspection of Anglican and Methodist Schools (SIAMS) Report Debenham High School – A Church of England Academy Gracechurch Street, Debenham, Suffolk IP14 6BL Current SIAMS inspection grade Outstanding Diocese St Edmundsbury & Ipswich Previous SIAS inspection grade Outstanding Date of academy conversion January 2011 Date of inspection 10 October 2017 Date of last inspection 11 December 2012 Type of school and unique reference number 11-16 Academy 136416 Headteacher Julia Upton Inspector’s name and number Gill Hipwell 480 School context The catchment area of this rural high school incorporates a small market town and several outlying villages. It is relatively small in relation to the county average and consistently over-subscribed, with around one third of its 677 pupils coming from outside the catchment area. Although average attainment on entry exceeds national percentages, some pupils face significant challenges. The school is growing and is in the process of extending its buildings. Academic progress and outcomes for all groups have been significantly above local and national averages for a number of years. Leadership is exceptionally stable; the current headteacher has been in post for five years and is only the fourth since the school’s foundation in 1964. After a lengthy interregnum there is a new incumbent in the parish. In 2016 the school was instrumental in setting up the Mid Suffolk Teaching Schools Alliance (MSTSA), in which the diocese is also a partner. The current director of the teaching school is an assistant headteacher at Debenham. The distinctiveness and effectiveness of Debenham as a Church of England school are outstanding • The depth of the Christian ethos and the extent to which every interaction focuses on the intrinsic worth of each individual lead to outstanding progress and personal development for pupils and adults. -

Examination Results Special 2014

Academic Year 2014-2015 Number 1 HIGH SCHOOL Maths, Computing and Arts Specialist School www.farlingaye.suffolk.sch.uk [email protected] 12th September 2014 EXAMINATION RESULTS SPECIAL 2014 Farlingaye High School Foundation AGM (with wine, nibbles and useful workshops for parents!) 7.00pm Thursday 18th September 2014 FORUM EXAM RESULT SPECIAL AM absolutely delighted to report that we had yet another excellent I summer with some of our best ever results at both GCSE and A level. We were “83% of grades were also delighted with the success of our at A* to C - our students at AS level and the Year 10 GCSE Statistics. The national papers once again second best ever and listed us as a highly performing school and much higher than the we were the highest listed school in the national average.” county. Our A level results were fantastic and confirmed our position as one of the most consistently top performing schools in the county. 31% of grades were at grade A*/A and 83% of the grades were A* to C - our second best ever and much higher than the national average. 66 students achieved at least 2A grades and a quarter achieved an A*. Our average total point score per student at 995 and average score per subject at 229 are extremely high and significantly above national averages. There were many superb individual performances. Particular credit goes to Lawrence Beaumont, Emily Ley and Sam Moody who all achieved at least three A* grades. As well as those gaining very high grades, we were equally pleased with the excellent performances from less able students who, whilst maybe not getting A and A* grades, exceeded their target grades and achieved the excellent individual results needed to secure Higher Education places. -

2021 Secondary Co-Ordinated Admissions Scheme

2021 SECONDARY CO-ORDINATED ADMISSIONS SCHEME This Scheme is formulated in accordance with the School Admissions Code which came into force on 19th December 2014. Trafford LA has formulated this Scheme in relation to each school in the Trafford area. The Governing Bodies/Trusts of the following schools/academies are the admission authorities for the secondary schools to which this scheme applies: Altrincham College; Altrincham Grammar School for Boys; Altrincham Grammar School for Girls; Ashton-on-Mersey School; Blessed Thomas Holford Catholic College; Broadoak School; Flixton Girls’ School; Loreto Grammar School; North Cestrian School; Sale High School; Sale Grammar School; Stretford Grammar School; Stretford High School; St Ambrose College; St Antony's Catholic College; Urmston Grammar School; Wellacre Academy and Wellington School. Trafford LA is the admission authority for Lostock High School. NORMAL ADMISSION ROUND (transfer from primary to secondary school) SEPTEMBER 2021 1. APPLICATION PROCEDURE i) In the autumn term of the offer year all parents of Year 6 children will be invited to submit an application. Information on how to apply will be sent to all parents of pupils resident in Trafford, at their home address. ii) An advertisement will be placed in the local press inviting parents who are resident in Trafford whose children may not currently be attending a Trafford primary school to submit an application. iii) Information will be sent to all parents by 12 September in the offer year and they will be asked to submit their application by 31 October, thereby ensuring that all parents have the statutory 6 week period in which to express their preferences. -

Report on the Second York Schools Science Quiz on Thursday 12 March, Thirteen Schools from in and Around York Came Together

Report on the Second York Schools Science Quiz On Thursday 12 March, thirteen schools from in and around York came together for the second York Schools Science Quiz. Twenty two school teams competed along with four teacher teams (put together from the teachers who brought the pupils along from the various schools) for the trophies and prizes. Each team consisted of two Lower Sixth and two Fifth Form pupils or four Fifth Form pupils for those schools without Sixth Forms. The schools represented were Manor CE School, Canon Lee School, The Joseph Rowntree School, Huntington School, Archbishop Holgate’s School, Fulford School, All Saints School, Millthorpe School, St Peter’s School, Bootham School, The Mount School, Selby High School and Scarborough College. The event took place as part of the York ISSP and also the York Schools Ogden Partnership, with a large thank you to the Royal Society of Chemistry and the Institute of Physics for some of the prizes, the Rotary Club of York Vikings for the water bottles and the Ogden Trust for the 8 GB memory sticks and Amazon Voucher prizes. The quiz was put together and presented by Sarah McKie, who is the Head of Biology at St Peter’s School, and consisted of Biology, Chemistry and Physics rounds alongside an Observation Challenge and a Hitting the Headlines round amongst others. At the end of the quiz the teams waited with bated breath for the results to be announced. It turned out that three teams were tied for second place, so a tie breaker was needed to separate them. -

All Saints Church First Female Vicar

Contacts at All Saints Vicar The Rev’d Clair Jaquiss 928 0717 [email protected] 07843 375494 Clair is in the parish on Tuesdays, Wednesdays & Sundays; or leave a message Associate Priest The Rev’d Gordon Herron 928 1238 [email protected] Reader Mary Babbage 980 6584 [email protected] Reader Emerita Vivienne Plummer 928 5051 [email protected] Wardens June Tracey 980 2928 [email protected] Nigel Glassey [email protected] 980 2676 PCC Secretary Caroline Cordery 980 6995 [email protected] Treasurer Michael Sargent 980 1396 [email protected] Organist Robin Coulthard 941 2710 [email protected] Administrator & Elaine Waters 980 3234 Hall Bookings [email protected] . ServicesServices Fourth Sunday of month: Eucharist Together at 10am All other Sundays: Eucharist at 10am (with Children’s Groups) Sunday Evenings: Evening Prayer at 6.30pm Tuesdays at 9.30am Eucharist (also on Holy Days - announced) All Saints Hale Barns with Ringway Hale Road, Hale Barns, Altrincham, Cheshire WA15 8SP Church and Office Open: Tuesday, Wednesday & Thursday 9am - 1pm Tel: 0161 980 3234 Email: [email protected] www.allsaintshalebarns.org Visible and Invisible... ‘So where is All Saints?’ they often ask me. It’s not just the stranger wondering where the parish church is, but often a long-term resident of the area who has never really registered where the parish church of Hale Barns actually is. I’ve often wondered at its invisibility. All Saints is a classic building of its time, designed to blend in with the new structures, domestic and commercial, that were springing up around it. -

School Admissions Guide for Parents 2021-2022

Primary and Secondary Education in Middlesbrough A Guide for Parents 2021 - 2022 Middlesbrough middlesbrough.gov.uk moving forward Introduction MIDDLESBROUGH COUNCIL This booklet aims to help you if your child is starting school for the first time, moving from primary to secondary education, transferring from one school to another or if you are new to the area. It describes admission arrangements for our primary and secondary schools. The Guide contains general information on education in Middlesbrough and lists each of the schools in the Local Authority (LA), together with admission arrangements, including the type of school, and the maximum number of places normally available in each school year. You are entitled to express a preference as to which primary or secondary school you want your child to attend. Details of how to do this are given in the booklet. Each school produces a prospectus. This contains information of a general nature about the day to day running of the school, including details of the admissions policy agreed by the school and the LA or Governing Body. If you would like a prospectus, contact the school concerned. If you require more details or clarification about admission arrangements, admission zones or education in general, please write to: School Admissions, Middlesbrough Council, Middlesbrough House, Corporation Road, Middlesbrough, TS1 1LT The information contained in this Guide is correct at the time of going to press. middlesbrough.gov.uk 1 Contents CONTENTS PAGE PART ONE ADMISSIONS ARRANGEMENTS 3 1. Types Of School 3 2. Nursery Education 3 3. School Admissions General Information 4 4. Primary School Admissions 11 5. -

Applying for a School Place for September 2018

Guide for Parents Applying for a school place for September 2018 City of York Council | School Services West Offices, Station Rise, York, YO1 6GA 01904 551 554 | [email protected] www.york.gov.uk/schools | @School_Services Dear Parent/Carer, and those with siblings already at a school, inevitably there are times when Every year the Local Authority provides parental preferences do not equate to places in schools for children in the City the number of available local places. of York. This guide has been put together to explain how we can help you through Please take the time to read this guide the school admissions process and to let carefully and in particular, take note of you know what we do when you apply the key information and the for a school place for your child and what oversubscription criteria for the schools we ask you to do. that you are interested in. It contains details of admissions policies and Deciding on your preferred schools for procedures and the rules that admissions your child is one of the most important authorities must follow. Reading this decisions that you will make as a guide before making an application may parent/carer. This guide contains some prevent misunderstanding later. If after information about our schools and our considering the information available services. We recommend that you visit here you need more information, please schools on open evenings or make an contact the School Services team who will appointment at a school prior to making be happy to assist you further. an application. -

(2002-2014) on Pupil Sorting and Social Segregation: a Greater Manchester Case Study

WP24 The Effects of English School System Reforms (2002-2014) on Pupil Sorting and Social Segregation: A Greater Manchester Case Study Working Paper 24 August 2017 The Effects of English School System Reforms (2002-2014) on Pupil Sorting and Social Segregation: A Greater Manchester Case Study Stephanie Thomson and Ruth Lupton 1 WP24 The Effects of English School System Reforms (2002-2014) on Pupil Sorting and Social Segregation: A Greater Manchester Case Study Acknowledgements This project is part of the Social Policy in a Cold Climate programme funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, the Nuffield Foundation, and Trust for London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders. We would like to thank Somayeh Taheri for her help with the maps in this paper. We would also like to thank John Hills, Anne West, and Robert Walker who read earlier versions for their helpful comments. Finally, sincere thanks to Cheryl Conner for her help with the production of the paper. Any errors that remain are, of course, ours. Authors Stephanie Thomson, is a Departmental Lecturer in Comparative Social Policy at the University of Oxford. Ruth Lupton, is Professor of Education at the University of Manchester and Visiting Professor at The Centre for Analyis of Social Exclusion, The London School of Economics and Political Science. 2 WP24 The Effects of English School System Reforms (2002-2014) on Pupil Sorting and Social Segregation: A Greater Manchester Case Study Contents List of figures ..................................................................................................................................... 3 List of tables ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 2. Changes to School Systems in the four areas .......................................................................... -

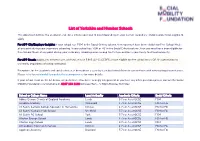

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Airedale Academy Wakefield 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints Catholic College Specialist in Humanities Kirklees 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints' Catholic High -

Evaluation Report September 2018

Evaluation Report September 2018 Authors: Dr Katharine M. Wells & Heather Black Together Middlesbrough & Cleveland Registered Charity 1159355 Registered Company 9196281 c/o The Trinity Centre, James Street, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, TS3 6LD www.togethermc.org.uk Acknowledgements Summer 2018 Feast of Fun was the product of 5 years of growth and development of the programme across Middlesbrough and Redcar & Cleveland. We would like to thank the hundreds of staff and volunteers whose time, energy and passion made Feast of Fun possible. Without you we would not be able to provide support to hundreds of local children and families who struggle during the long summer holidays. We would also like to thank all the parents, children and volunteers who kindly took time to be interviewed, giving us valuable insights into the need for holiday provision and the difference it makes. This year saw more businesses and organisations partner with Feast of Fun than ever before. We would especially like to thank Quorn Foods, the North York Moors National Park Centre at Danby, the Bowes Museum, MIMA, the National Literacy Trust, Kids Kabin, Middlesbrough College, Middlesbrough Environment City, and Northern Rail. Thanks also go to Middlesbrough Council Financial Inclusion Group, Meals and More and the Ballinger Charitable Trust, for the funding provided to support the programme. We are also indebted to the many churches and individuals who gave donations and organised fundraising activities to support Feast of Fun. Feast of Fun 2018 Evaluation Report Executive summary Background There have been growing concerns about childhood hunger during school holidays in the UK. Here in Middlesbrough and in Redcar & Cleveland the Feast of Fun programme aims to alleviate some of the challenges faced by local families during the school holidays. -

SMF 8 July 2020

SCHOOLS MANAGEMENT FORUM Notes of meeting held on Wednesday 15th January 2020, 8:15am at Acklam Grange Community Learning Centre Attending: Andrea Crawshaw Chair / Acklam Grange School Judi Libbey Head of Resources and SEN – Middlesbrough Council Dianne Nielsen Senior Accounting Officer – MBC William Guthrie PVI Afzal Kushi PVI Rob Brown Director of Education, Prevention and Partnerships – MBC Beverley Hewitt-Best Newham Bridge Primary School Mary Brindle Macmillan Academy Helen Malbon Viewley Hill Primary School Julia Rodwell Park End Primary School Leanne Chilton RTMAT Amy Young Captain Cook Primary School Joanne Smith Breckon Hill Primary School Barrie Cooper Councillor/Executive member for Children’s Services Jackie Walsh Green Lane Primary School Jo Smith Beverley School Gary Maddison Strategic School Planning Manager - MBC Sarah Davidson Head of Achievement and Inclusion - MBC Sarah Lymer Linthorpe Community Primary School 1. Apologies for Absence / Any Items for AOB Chris Wain – Pallister Park Primary Emma Watson – The Avenue Primary Adam Cooper – Abingdon Primary Craig Povey – Finance Business Partner - MBC 2. Minutes of Previous Meeting / Matters Arising AC provided clarification around the concern that Councilors had written to Head Teachers requesting exceptions on appeals that had already been heard and completed. AC understands that the process is complex however once an appeal has been heard – it is binding on the parent, governors and the school for a year. It was welcomed that Councilors had received training and further information on the Admissions Process and TVCA Update – Three bids were submitted in partnerships between the Local Authority and schools. All three bids were unsuccessful and schools have been asked to reconsider bids. -

Is Your School

URN DFE School Name Does your Does your Is your Number school school meet our school our attainment eligible? Ever6FSM criteria? 137377 8734603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ncriteria? N N 137083 3835400 Abbey Grange Church of England Academy N N N 131969 8654000 Abbeyfield School N N N 138858 9284069 Abbeyfield School N Y Y 139067 8034113 Abbeywood Community School N Y Y 124449 8604500 Abbot Beyne School N Y Y 102449 3125409 Abbotsfield School N Y Y 136663 3115401 Abbs Cross Academy and Arts College N N N 135582 8946906 Abraham Darby Academy Y Y Y 137210 3594001 Abraham Guest Academy N Y Y 105560 3524271 Abraham Moss Community School Y Y Y 135622 3946905 Academy 360 Y Y Y 139290 8884140 Academy@Worden N Y Y 135649 8886905 Accrington Academy N Y Y 137421 8884630 Accrington St Christopher's Church of England High School N N N 111751 8064136 Acklam Grange School A Specialist Technology College for Maths and Computing N Y Y 100053 2024285 Acland Burghley School Y Y Y 138758 9265405 Acle Academy N N Y 101932 3074035 Acton High School Y Y Y 137446 8945400 Adams' Grammar School N N N 100748 2094600 Addey and Stanhope School Y Y Y 139074 3064042 Addington High School Y Y Y 117512 9194029 Adeyfield School N Y Y 140697 8514320 Admiral Lord Nelson School N N N 136613 3844026 Airedale Academy N Y Y 121691 8154208 Aireville School N N Y 138544 8884403 Albany Academy N N N 137172 9374240 Alcester Academy N N N 136622 9375407 Alcester Grammar School N N N 124819 9354059 Alde Valley School N N Y 134283 3574006 Alder Community High School N Y Y 119722 8884030