National Report On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Historical Perspective on Animal Power Use in South Africa

An historicalAnimal traction perspective in South Africa: empowering on animal rural communities power use in South Africa by Bruce Joubert Early reports Company to establish a replenishment station The first known reports of animal traction in for their ships, which plied between Europe and South Africa come from the early European the far East. The Dutch, in Holland, used explorers and date back to as early as 1488, mainly draft horses to pull their carts, wagons when Bartholomeu Dias first sighted the Cape and farm implements. Owing to the nature of and named the bay where he made his land fall sea travel in those days van Riebeeck brought Angra dos Vaqueiros, which means `Bay of no horses or carts with him. Furthermore he Cowherds' (Burman, 1988). brought no long-term supplies of food, as the Dutch East India Company expected his people The western and south-western Cape was at to grow their own grain and vegetables and to that time inhabited by the `Khoi-khoi' who barter animals from the Khoi-khoi. For belonged to the same racial group as the bartering purposes they offered copper wire, `Bushmen'. Early Dutch settlers named these copper plates, beads, tobacco and liquor in people `Hottentots' after their language, which exchange for cattle and fat-tailed sheep. The had many clicks. The Khoi-khoi were building of the first European settlement was pastoralists and kept large herds of cattle and achieved largely using human power, although sheep. They were semi-nomadic and moved a few oxen bartered from the Khoi-khoi were about within a large but defined area as the used to pull a carpenter's cart. -

High Horses Horses, Class and Socio-Economic Change in South Africa1

Chapter 7 ❈ High Horses Horses, Class and Socio-economic Change in South Africa1 ‘Things are in the Saddle and ride mankind.’ 2 n the first half of the twentieth century there was a seismic shift in the Irelationship between horses and humans in commercial South Africa as ‘horsepower’ stopped implying equine military-agricultural potential and came to mean 746 watts of power.3 By the 1940s the South African horse industry faced a crisis. There was an over-production of horses, exacerbated by restrictions imposed by the Second World War, which rendered export to international markets difficult.4 Farm mechanisation was proceeding apace and vehicle numbers were doubling every decade.5 As the previous chapter has shown, there were doomed attempts to slow the relentless mechanisation of state transport. As late as 1949 the Horse and Mule Breeders Association issued a desperate appeal to the minister of railways and transport to stall mechanisation and use animal transport wherever possible.6 Futile efforts were made to reorientate the industry towards slaughtering horses for ‘native consumption’ or sending chilled equine meat to Belgium.7 Remount Services had been transferred to the Department of Agriculture, a significant bureaucratic step reflecting the final acknowledgement of equine superfluity to the modern military. As the previous chapter discussed, the so-called ‘Cinderella of the livestock industry’ had to reinvent itself to survive.8 A new breed of horses thus entered the landscape of the platteland: the American Saddlebred.9 Unlike the horses that had preceded them, these creatures were show horses. The breed was noted for its showy action in all Riding High 07.indd 171 2010/05/31 12:04 PM Riding High paces, its swanlike neck with ‘aristocratic arch’ and its uplifted tail. -

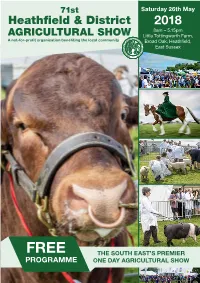

Final Programme 2018

71st Saturday 26th May Heathfield & District 2018 8am – 5.15pm AGRICULTURAL SHOW Little Tottingworth Farm, ICUL GR TU A not-for-profit organisation benefiting the local community A R A Broad Oak, Heathfield, D L L S E I O East Sussex F C H I T E A T E Y H FREE THE SOUTH EAST’S PREMIER PROGRAMME ONE DAY AGRICULTURAL SHOW F R E E M A N F O RMA N CONTENTS 4 MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION FORM 17 WOMEN’S INSTITUTE Experts in handling the sale of a wide range of superb properties from Apartments and Pretty Cottages up to exclusive Country Homes, Estates and Farms 6 TIMETABLE OF EVENTS 17 MICRO BREWERY FESTIVAL 8 SOCIETY OFFICIALS 26 VINTAGE TRACTOR & WORKING STEAM SOLD SOLD 9 STEWARDS 18 NEW ENTERPRISE ZONE 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 20 COUNTRY WAYS 12 SPONSORS & DONATIONS 11 FARMERS MARKET 14 COMPETITIONS & ATTRACTIONS 22 ARTS & CRAFTS MARQUEE 27 TRADE STANDS 24 SUSSEX FEDERATION OF YOUNG FARMERS’ CLUB 33 CATTLE SECTION SOLD SOLD 50 SHOWGROUND MAP 24 EDUCATION AREA 53 SHEEP SECTION 24 PLUMPTON COLLEGE 48 PIG SECTION 16 DISPLAYS 61 HORSE SECTION LIABILITY TO THE PUBLIC AND/OR EXHIBITORS ® Country Homes Battle 01424 777165 Country Homes Tunbridge Wells 01892 615757 A) All visitors to premises being used by the Society accept that the Society its Officers, employees or Est 1982 May 2018 servants shall have taken all reasonable steps to ensure the safety of such visitors while in or upon Battle Burwash Hawkhurst Heathfield the premises, or while entering or leaving the same. B) All visitors to premises being used by the Society shall at all times exercise all reasonable care 01424 773888 01435 883800 01580 755320 01435 865055 while in or upon the premises, or while entering or leaving the same. -

Download Full

Proceedings of the World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, 11.550 Genetic variability and relationships among nine southern African and exotic cattle breeds L. van der Westhuizen1,2, M.D. MacNeil1,2,3, M.M. Scholtz1,2 & F.W.C. Neser2 1 ARC-Animal Production Institute, Private Bag X2, 0062, Irene, South Africa [email protected] (Corresponding Author) 2 Department of Animal, Wildlife and Grassland Sciences, UFS, P.O. Box 339, Bloemfontein, 9300, South Africa 3 Delta G, 145 Ice Cave Road, MT 59301, Miles City, USA Summary An existing 11 microsatellite marker database that resulted from parentage verification in response to requests from industry, was used to assess genetic diversity among nine breeds of cattle. These breeds were drawn from B. indicus (Boran (BOR) and Brahman (BRA)), B. taurus (Angus (ANG) and Simmental (SIM)), and B. taurus africanus (Afrikaner (AFR), Bonsmara (BON), Drakensberger (DRA), Nguni (NGU), and Tuli (TUL)). Due to the cost of genotyping, genetic diversity studies using SNPs rely on relatively low numbers of animals to represent each of the breeds. Large numbers of animals have been genotyped for parentage verification using microsatellite markers, therefore, the microsatellite information on large numbers of animals has the potential to provide more accurate estimates of genomic diversity. A minimum of 300 animals were randomly chosen from each breed and were used to assess within- and between breed genetic diversity. All breeds had high levels of heterozygosity and minimal inbreeding. There were distinct differences among the three groups of cattle, but also support for the notion of taurine influence in some of the Sanga and Sanga-derived breeds. -

Canada's Great Victorian-Era Exposition and Industrial Fair Toronto, August 30Th to September 11Th, 1897

w ^' :^^^mi^i^^ ^^Jk^ /^ wJCJjJ'^^jt^^M^MiS i| K^"^ f^v' ism WutM^i'^mms^ sWfi'" -^ ^^^W'''^ ; NStki%^'^^^^^^.^- 97' I sgraBKOs INDUSTRIAL; mM ^^'^^^:^^^^T^- S3' epti y^ ^^r«i The EDITH and LORNE PIERCE COLLECTION o/CANADIANA iiueeris University at Kingston \ BEST OF ALL BEST OF ALL ^V^KDA'S c G/?e, r Victorian-Era t^ t^ Jr* JF* J* ^* t^^ ^* ^^ ^^ j^ t^ t^ eiJ* 1^ ^^ e^*' e^^ t^^ ^^ fSr' «^*' t^ t^^ W* -« t^* e^*' e^* «^^ e^* f^ t^ «^ «^ «^ Exposition e(5* «^* e^* «^* e^* t^* e^* ^^ 9^* t^ e^* «^^ e^** e,^'' e^^ Industrial Fair ^-^jjs^ AUGUST 30th to SEPTEMBER I Ith, 1697 THE NATIONAL E2a'OSITION OF CANADA'S RESOURCES COMPETITION OPEN TO THE WORLD $55,000 in Premiums RULES AND REGULATIONS, Etc. EXTRA NEW SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS. THE CROWNING EVENT OF THE JUBILEE YEAR. EXHIBITION OFFICES: 82 KING ST. EAST, TORONTO THE MAIt JOB PRINT, TORONTO ^^^^^^^,^^^^^^^^^^^»f,f,f>»f,^,f>^,^,f>^,^^^^^^ o CL X LJ ^;-V^ *v^- •>' V *^ -^' I/\DE\ TO PRIZE LIST PAGE Officers and Directors 4 Rules and Regulations 5 to 12 Horse Department 13 to 22 Pony Exhibits 19. 20 Boy Riders 22 Speeding in the Ring 23 to 26 Notice of Auction Sale of Live fctock 27 Cattle 26 to 36 Sheep 35 to 43 Pigs 43 to 48 Poultry and Pigeons 48 to 61 Dairy Products and Utentils 61 to 64 Grains, Roots and Vegetables 64 to 67 Horticultural Department 68 to 75 Honey and Apiary Supplies 75 to 77 Minerals and Natural History 77 Implements 77, 78 Engines, Machinery, Pumps, etc 78, 79 Safes, Hardware, Gates and Fencing 80 Gas Fixtures, Metal Work and House Furnishings — 81 Leather, Boots and Shoes -

Breeding Admixture of Cattle Populations Kept in the Thabo Mofutsanyane District

BREEDING ADMIXTURE OF CATTLE POPULATIONS KEPT IN THE THABO MOFUTSANYANE DISTRICT NOMPILO LUCIA HLONGWANE August 2015 © Central University of Technology, Free State BREEDING ADMIXTURE OF CATTLE POPULATIONS KEPT IN THE THABO MOFUTSANYANE DISTRICT by NOMPILO HLONGWANE Dissertation submitted in fulfilments of the requirements for the degree For the degree MAGISTER TECHOLOGIAE: AGRICULTURE in the Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences Department of Agriculture at the Central University of Technology, Free State PROJECT SUPERVISOR: Prof DO Umesiobi [PhD, FUTO; (MAHES, UFS)] CO-SUPERVISOR: Dr BJ Mtileni [PhD, SUN] CO-SUPERVISOR: Dr SO Makina [PhD, UP] August ii © Central University of Technology, Free State DECLARATION I, Nompilo Lucia Hlongwane, student number------------------, declare that the dissertation: Breeding admixture of cattle populations kept in the Thabo Mofutsanyane District, submitted to the Central University of Technology, Free State for the Magister Technologies: AGRICULTURE is my own independent work and that all the sources used and quoted have been acknowledged by means of complete references; and complies with the code of academic integrity, as well as other relevant policies, procedures, rules and regulation of the Central University of Technology, Free State; and has not been submitted before to any institution by myself or any other person in fulfillment (or partial fulfillment) of the requirements for the attainment of any qualification. I also disclaim the copyright of this dissertation in favour of the Central University of Technology, Free State. Nompilo L Hlongwane DATE iii © Central University of Technology, Free State ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank the Almighty God, for giving me the inner strength and ability to accomplish this study. -

Estimation of Genetic and Non-Genetic Parameters for Growth Traits in Two Beef Cattle Breeds in Botswana

ESTIMATION OF GENETIC AND NON-GENETIC PARAMETERS FOR GROWTH TRAITS IN TWO BEEF CATTLE BREEDS IN BOTSWANA Kethusegile Raphaka Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Science (Agriculture) (Animal Sciences) University of Stellenbosch, South Africa Supervisor: K. Dzama, Associate Professor Department of Animal Sciences March, 2008 University of Stellenbosch Stellenbosch Declaration I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that it has not, as a whole or partially, been submitted to any other university for the purpose of acquiring a degree. Signed: ___________________________ Name: ____________________________ Date: _____________________________ Copyright ©2008 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Summary ESTIMATION OF GENETIC AND NON-GENETIC PARAMETERS FOR GROWTH TRAITS IN TWO BEEF CATTLE BREEDS IN BOTSWANA Candidate: Kethusegile Raphaka Supervisor: Prof. K. Dzama Department: Animal Sciences Faculty: Agricultural and Forestry Sciences University: Stellenbosch Degree: MSc Agric Research conducted on beef cattle in Botswana investigated both growth and reproduction. These studies however, did not specifically determine the influence of the different environmental factors on growth in the Tswana and Composite beef cattle breeds. The establishment of a national beef herd recording and performance testing scheme requires knowledge on the appropriate adjustment methods of field data for the fixed effects such as sex of calf and age of dam. A fair comparison of birth and weaning weights between male and female calves, and calves born from young, mature and old dams will be derived from these adjustment factors. There is no information on adjustment factors for the Tswana and Composite cattle breeds in the country. Genetic parameters for growth traits in these breeds are not known and are needed for the implementation of the performance scheme in Botswana. -

The Stoneleigh Herd

HERD FEATURE THE STONELEIGH HERD The Stoneleigh Herd of Sussex cattle was founded in 2002, a year after Debbie Dann and Alan Hunt had bought the RASE’s herd of rare breed White Park Cattle. White Parks, for all their good looks and photogenic charm, are not the most commercial of breeds so they wanted a breed to complement the White Parks and that would pay the bills and ensure the cattle weren’t just a glorified hobby. After looking at a number of native breeds the selection was narrowed down to South Devons and Sussex (Debbie is originally from Hersmonceux in East Sussex). Sussex easily trumped the South Devons! The dispersal of Mike Cushing’s Coombe Ash Herd in May 2002 provided the ideal opportunity to buy some foundation cows and four cows with calves at foot and back in calf again found themselves travelling up the M40 to Warwickshire. Coombe Ash Godinton 5th, bought as a calf at foot from the Coombe Ash dispersal sale and her heifer calf summer 2013 Debbie’s day job at that time was to run all the competitive classes for the Royal Show and Alan was and still is the Estate Manager for the Royal Showground’s farmland. Since 2007 Debbie has been Breed Secretary for the Longhorn Cattle Society. This means that both Alan and Debbie have full time jobs and the cattle are mostly managed outside of work hours and have to be pretty low maintenance. Stoneleigh Godinton 2nd and calf Cows are housed over the winter as all the grazing is rented and the cattle are easier to manage when they are indoors when the owners are working full time. -

South 4Fric4 (1400-1881)

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 7, Nr 4, 1977. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za ~ILIT 4RY USE OF 4~1~4LS ~ SOUTH 4FRIC4 (1400-1881) LT ~c:GILL .4.LEX.4.~[)E~* Introduction credibly tough Cape Horse. This new breed was also known as the 'Hantam'.1 The extent to which military operations de- pended on animals prior to the gradual From the Cape Horse two indegenous breeds mechanisation of armed forces which has were developed as the horse, with the white \ taken place this century, is seldom fully settlers, spread further east and north. These' appreciated by the soldier in a modern army. were the 'Boerperd', which accompanied the In South Africa, with its relatively short Voortrekkers on the Great Trek, and the Ba- history profusely studded with bellige- suto Pony.2 rent actions ranging from internecine tribal squabbles through riots, rebellions, civil Responses of the non.white races to horses wars, invasions and conquests to inter- national conflicts, animals have played a sig- The introduction of mounted soldiers into nificant role in the conduct of military affairs. South Africa had an electrifying effect on the The varied topography and climate of the non-white races. Together with their use of sub-continent has enabled animals to be guns, it was this factor which gave the utilized under many conditions which have whites almost constant military superiority taxed their capabilities in various fields to over them. Yet, curiously, it was only the the utmost. Basuto who, in later years, adopted the horse on a large scale, and even then not as a com- It is the aim of this paper to examine bat animal. -

Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Les appellations employées dans cette publication et la présentation des données qui y figurent n’impliquent de la part de l’Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture aucune prise de position quant au statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni quant au tracé de leurs frontières ou limites. Las denominaciones empleadas en esta publicación y la forma en que aparecen presentados los datos que contiene no implican de parte de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica de países, territorios, ciudades o zonas, o de sus autoridades, ni respecto de la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and the extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. Tous droits réservés. Aucune partie de cette publication ne peut être reproduite, mise en mémoire dans un système de recherche documentaire ni transmise sous quelque forme ou par quelque procédé que ce soit: électronique, mécanique, par photocopie ou autre, sans autorisation préalable du détenteur des droits d’auteur. -

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

From Paddling the Zambezi to Galloping Across South African Savanna, We’Ve Come up with the Adventures You Can’T Miss

From paddling the Zambezi to galloping across South African savanna, we’ve come up with the adventures you can’t miss. They’ll transport you through wilderness, introduce you to stunning landscapes and deliver some mighty animals along the way. ETHIOPIA UGANDA KENYA REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO TANZANIA ZAMBIA NAMIBIA BOTSWANA SOUTH AFRICA 100 get lost ISSUE 47 get in the know One elephant can hear another’s trumpet from 10 kilometres away. get in the know The Zambezi, at 3450 kilometres, fows through six countries: Zambia, Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. ISSUE 47 get lost 101 walking with giants For a mORe sErEnE take oN ThE tradiTIonAl safAri, HanNA JoNes lacES up her HikIng boOts fOr cloSe encouNtErs Of The wild kInD IN KeNya. Promises have been made: hike to the top of One of this walk’s unique aspects is its a huge rock called Nyasura in the distance guides. Hailing from the Samburu tribe, who and be rewarded with spectacular views live mainly in north central Kenya (they’re over the plains. After about 15 minutes or related to, but distinct from, the Maasai so, it isn’t the vista that proves to be the people), they lead the safaris dressed most magical element of the climb: we can in traditional attire. This includes shoes hear men singing. Since we’re in the middle made from old tyres – and if you doubt the of nowhere, Kenya, this comes as a bit of a effectiveness of such footwear, I’m here to tell surprise, but it does provide the impetus to you those old Bridgestones seemed to offer get moving a little faster towards the summit.