Paulist Associates Formation Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Patrick Publishing

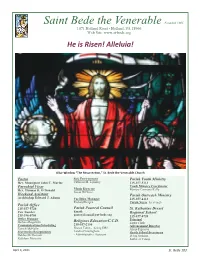

Saint Bede the Venerable Founded 1965 +ROODQG5RDG+ROODQG3$ :HE6LWHZZZVWEHGHRUJ ,ĞŝƐZŝƐĞŶ͊ůůĞůƵŝĂ͊ ůƚĂƌtŝŶĚŽǁ͞dŚĞZĞƐƵƌƌĞĐƟŽŶ͕͟^ƚ͘ĞĚĞƚŚĞsĞŶĞƌĂďůĞŚƵƌĐŚ͘ Pastor 6DIH(QYLURQPHQW Parish Youth Ministry 5HY0RQVLJQRU-RKQ&0DULQH &DWKOHHQ0/\QVNH\ Parochial Vicar <RXWK0LQLVWU\&RRUGLQDWRU 5HY7KRPDV'2¶'RQDOG 0XVLF'LUHFWRU 0DULW]D&DUPRQD.HOO\ 6XVDQ'L)ORULR Weekend Assistant Parish Outreach Ministry $UFKELVKRS(GZDUG-$GDPV )DFLOLWLHV0DQDJHU 5LFKDUG%HUJHQ 3DULVK1XUVH.ULV,QJOH Parish Office Parish Pastoral Council St. Katharine Drexel Fax Number (PDLO Regional School SDVWRUDOFRXQFLO#VWEHGHRUJ 2IILFH0DQDJHU Religious Education/C.C.D. 3ULQFLSDO %DUEDUD5RJRZVNL /DXUD&ODUN &RPPXQLFDWLRQV6FKHGXOLQJ $GYDQFHPHQW'LUHFWRU 3DWULFN0F1DOO\ 6KDZQ7RELQ$FWLQJ'5( $OLFLD)LJXHURD 6HFUHWDULHV5HFHSWLRQLVWV /DQGUD&XQQLQJKDP *UDGH6FKRRO6HFUHWDULHV 'HEELH0F'HUPRWW $GPLQLVWUDWLYH$VVLVWDQW 'HEUD*XDULQR .DWKOHHQ0HUFXULR .DWKOHHQ<RXQJ Ɖƌŝůϰ͕ϮϬϮϭ ϭ ^ƚ͘ĞĚĞϭϬϯ Mary of Magdala came to the tomb early in the morning, while it was still dark, and saw the stone removed from the tomb. -RKQ He is Risen! Alleluia! 0\'HDU3DULVKLRQHUV JRRGQHZVWRNQRZWKDWWUXWKLVLPPRUWDO:HFDQ VXSSUHVVWUXWKDFFXVHLWRIEHLQJDOLHFRQGHPQLW :K\GRZHUHMRLFHWRGD\RQ WRUWXUHLWNLOOLWEXU\LWLQWKHJUDYHEXWRQWKHWKLUG WKLV(DVWHU6XQGD\"$IWHUDOOWKH GD\WUXWKZLOOULVHDJDLQ VWRU\RIWKHVXIIHULQJDQGGHDWKRI 5HPHPEHUWKLVDQGGRQRWJLYHXSRQWUXWKHYHQ -HVXVRQ*RRG)ULGD\LVWKHVWRU\RI ZKHQHYHU\ERG\VHHPVWRJLYHXSRQLW'RQRWJLYH WKHWULXPSKRIIDOVLW\RYHUWUXWKRI XSRQWUXWKGRQRWJLYHXSRQMXVWLFH'RQRWJLYHXS ZĞǀ͘DŽŶƐŝŐŶŽƌ LQMXVWLFHRYHUMXVWLFHRIHYLORYHU -

May 20Th, 2021

May 20th, 2021 Pentecost and Paulist Ordination The feast of Pentecost is this Sunday, May 23rd. As the Holy Spirit breathes new life into the hearts of the faithful, we're excited to celebrate with a little more togetherness! Pentecost is a yearly reminder to share Christ's light, and gives us an opportunity to consider how we can bring God's ministry into the world. This spirit of ministry provides us with the perfect backdrop to welcome two new priests into the Paulist Fathers! The staff of St. Paul's has also been focused on ministry this week. With the world ever so slowly opening back up, St. Paul's looks forward to seeing you! Keep an eye out for events as we rebuild the ministries that make up our vibrant and thriving community. Join us in celebrating the priestly ordination of Deacon Michael Cruickshank, CSP, and Deacon Richard Whitney, CSP, this Saturday, May 22nd at 11AM at St. Paul the Apostle Church! Bishop Richard G. Henning will be the principal celebrant. The public is welcome to attend the mass! In addition, it will be broadcast live at paulist.org/ordination as well as on the Paulist Fathers’ Facebook page and YouTube channel. If you can't attend the ceremony, our two new Paulist Fathers will be saying their First Masses at the 10AM and 5PM masses on Sunday, May 23rd. However you're able to participate, we hope you will join us in celebrating these men as they journey into God's ministry! Ordination 2021 A Note from Pastor Rick Walsh This weekend we celebrate the presbyteral ordination of two Paulists, Michael Cruickshank and Richard Whitney. -

CHURCH of ST. PAUL the APOSTLE, 8 Columbus Avenue (Aka 8-10 Columbus Avenue, 120 West 60Th Street), Manhattan

DESIGNATION MODIFIED SEE ADDENDUM Landmarks Preservation Commission June 25, 2013, Designation List 465 LP-2260 CHURCH OF ST. PAUL THE APOSTLE, 8 Columbus Avenue (aka 8-10 Columbus Avenue, 120 West 60th Street), Manhattan. Built 1875-85; initial design attributed to Jeremiah O’Rourke; upper walls of towers, c. 1900; “Conversion of Paul” bas-relief by Lumen Martin Winter, 1958 Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1131, Lot 31 On June 11, 2013, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a hearing (Item No. 2) on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Church of St. Paul the Apostle and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site.1 The hearing was duly advertised according to provisions of law. Five people spoke in support of designation, including representatives of New York State Senator Brad Hoylman, Community Board 7, the Historic Districts Council, Landmark West! and the Society for the Architecture of the City. One person, representing Father Gilbert Martinez, CSP, spoke in opposition to designation. Summary The Church of St. Paul the Apostle, located at the southwest corner of Columbus Avenue and 60th Street in Manhattan, was built in 1875-85. Commissioned by the Missionary Society of St. Paul the Apostle, commonly called the Paulist Fathers, it is an austere and imposing Medieval Revival style design, loosely based on Gothic and Romanesque sources. The Paulists trace their origins to 1858 when Isaac Hecker traveled to Rome and received permission from Pope Pius IX to organize an American society of missionary priests. The following year, Archbishop John Hughes of New York asked Hecker’s group to establish a parish on Manhattan’s Upper West Side and a simple brick church was constructed. -

October 4, 2020 Pastor’S White Board the Weeks Ahead

OLD ST. MARY’S CHURCH OUR PARISH MISSION Founded in 1833, Old St. Mary’s parish is the first Catholic parish in the Chicago area. Guided for more than a century by the vision of the Paulist Fathers, we are a diverse and welcoming community dedicated to serving the spiritual needs of the Loop, South Loop and the greater Chicago area. As a unified Church and School community, Old St. Mary’s Parish promotes the mission of the Paulist Fathers to welcome those who have been away from the church, to build bridges of respect and collaboration with people of diverse backgrounds and religions, and to promote justice and healing in our society. OLD ST. MARY’S CHURCH - 1500 S. MICHIGAN AVENUE, CHICAGO, IL 60605 CHICAGO’S FIRST CATHOLIC PARISH ESTABLISHED IN 1833 THE PAULIST FATHERS SERVING OUR PARISH SINCE OCTOBER 12, 1903. Page Two Old St. Mary’s Church October 4, 2020 Pastor’s White Board The Weeks Ahead... This week we launch into the busy month of October. October is usually busy. At the parish we usually have our ministry fair; fall sports are off and running; the Chicago Marathon is running by the church, and people are gearing up for the rest of the year and the holidays…. Even though we are more limited in our regular activities we still have events happening. Today, I invite you to look at and consider these reminders. VOTE. Check our website for ideas on how to form your conscience. Catholic teaching is very clear that individual consciences are inviolable. That being said, we are also called to have well formed consciences by engaging in research and debate with others and ourselves to figure out the right issues and right candidates to vote for. -

Bartholomew Landry Ordained at ST. PAUL the APOSTLE

SUMMER 2007 A LOOK AT THE PAST AND THE FUTURE BARTHOLOMEW LANDRY In this issue you will read about the celebration ORDAINED of the Paulists’ 50th anniversary of ministry at AT ST. PAUL The Ohio State University. However, one THE APOSTLE Silently, using might say that an ancient ritual gesture, Bishop our Paulist ties Houck lays his to the Diocese of Columbus go back to hands on the its very beginning. Why do I say that? candidate for A bit of history… ordination. General William Rosecrans was a professor at the United States Military Academy before his service in the Union Army. In the 1840s, he became a Catholic, and wrote to his brother Sylvester, a student at Kenyon College, encouraging him to explore Catholicism. He did so and entered the church. Sylvester Rosecrans studied for the priesthood and was ordained in 1852. A decade later, he was consecrated auxiliary bishop for the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. In 1868, he was named the founding bishop of The newly ordained Father Landry faces his fellow priests. the Diocese of Columbus. Father Duffy, FatherPaulist Landry, President Bishop Father Houck, John Father Duffy, D esiderio?,C.S.P., Father Father Landry, Bishop Houck, Father Gil Martinez, C.S.P., pastorBoadt? of St. ......Paul the Like any good “Paulist,” General Apostle, and Father Steve Bossi, C.S.P., Director of Formation. Father Landry greets the Rosecrans, one might say, evangelized assembly at his first Mass. his brother. But there is more to the Paulist story and the General. His son P aulist Father anointed Landry’s hands in East Troy, Wisconsin, charism of evangelization, “I have looked Adrian entered our community and Bartholomew Landry was with chrism. -

The Exultation of the Holy Cross September 14, 2014

THE EXULTATION OF THE HOLY CROSS SEPTEMBER 14, 2014 ST. ELIZABETH OF HUNGARY CHURCH CLASSES FOR FIRST COMMUNION will begin soon. If you have children who will be receiving their First Communion, please sign the list in the back of the Church, or call the parish office at 503-222-2168 MARTHA & MARY MINISTRIES —A second collection will be taken this weekend for the support of Martha & Mary Ministries, whose mission is to promote dignity at end of life through compassionate care and presence, spiritual support and community education. THE GREAT ADVENTURE: A Quick Journey through the Bible St. Francis Parish in Sherwood is offering a series of Adult Education presentations on Wednesday evenings at 7:00 PM at the Parish Center on September 3, 10, 17 and 24. A second series entitled The Bible and the Mass: The Jewish Roots of Christian Liturgy will be offered in October. For more information contact Dee Campbell, dee.campbellymail.com. A list of the classes is on the bulletin board. WHO ARE THE PAULISTS? How are they 'different" from the Franciscans, the Jesuits, or Diocesan priests? Fr. Charlie Brunick, CSP will present a 3-part series to explain why the Paulist Priests are unique in their mission and goals. Each session will be at St. Philip Ned Church, SE l& and Division Street, from 10:45 to 11:45 am following the 9:30 am Mass. September 28 Who is "Servant of God?" ----Isaac Hecker (Founder) October 12 The Mission and Charisms (gifts) of the Paulist Fathers October 26 The Paulist Associates----Collaborators in Mission AWAKENING FAITH - The Returning Catholic Ministry at Our Lady of the Lake Church invites inactive and semi-active Catholics to come together to discuss their faith The Awakening Faith program is structured to invite conversation and bonding between people. -

Catholic Constitutionalism from the Americanist Controversy to Dignitatis Humanae Anna Su University of Toronto Faculty of Law

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 91 | Issue 4 Article 7 6-2016 Catholic Constitutionalism from the Americanist Controversy to Dignitatis Humanae Anna Su University of Toronto Faculty of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation 91 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1445 (2016) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\91-4\NDL407.txt unknown Seq: 1 16-MAY-16 14:35 CATHOLIC CONSTITUTIONALISM FROM THE AMERICANIST CONTROVERSY TO DIGNITATIS HUMANAE Anna Su* ABSTRACT This Article, written for a symposium on the fiftieth anniversary of Dignitatis Humanae, or the Roman Catholic Church’s Declaration on Religious Freedom, traces a brief history of Catholic constitutionalism from the Americanist controversy of the late nineteenth century up until the issuance of Dignitatis Humanae as part of the Second Vatican Council in 1965. It argues that the pluralist experiment enshrined in the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution was a crucial factor in shaping Church attitudes towards religious freedom, not only in the years immediately preceding the revolutionary Second Vatican Council but ever since the late nineteenth century, when Catholicism became a potent social force in the United States. This history offers an oppor- tunity to reflect on what the new global geography of Catholicism portends in the future. -

CHURCH of ST. PAUL the APOSTLE, 8 Columbus Avenue (Aka 8-10 Columbus Avenue, 120 West 60Th Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 25, 2013, Designation List 465 LP-2260 CHURCH OF ST. PAUL THE APOSTLE, 8 Columbus Avenue (aka 8-10 Columbus Avenue, 120 West 60th Street), Manhattan. Built 1875-85; initial design attributed to Jeremiah O’Rourke; upper walls of towers, c. 1900; “Conversion of Paul” bas-relief by Lumen Martin Winter, 1958 Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1131, Lot 31 On June 11, 2013, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a hearing (Item No. 2) on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Church of St. Paul the Apostle and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site.1 The hearing was duly advertised according to provisions of law. Five people spoke in support of designation, including representatives of New York State Senator Brad Hoylman, Community Board 7, the Historic Districts Council, Landmark West! and the Society for the Architecture of the City. One person, representing Father Gilbert Martinez, CSP, spoke in opposition to designation. Summary The Church of St. Paul the Apostle, located at the southwest corner of Columbus Avenue and 60th Street in Manhattan, was built in 1875-85. Commissioned by the Missionary Society of St. Paul the Apostle, commonly called the Paulist Fathers, it is an austere and imposing Medieval Revival style design, loosely based on Gothic and Romanesque sources. The Paulists trace their origins to 1858 when Isaac Hecker traveled to Rome and received permission from Pope Pius IX to organize an American society of missionary priests. The following year, Archbishop John Hughes of New York asked Hecker’s group to establish a parish on Manhattan’s Upper West Side and a simple brick church was constructed. -

A Theology of Ecclesial Charisms with Special Reference to the Paulist Fathers and the Salvation Army

A Theology of Ecclesial Charisms with Special Reference to the Paulist Fathers and The Salvation Army by James Edwin Pedlar A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Department of Theology of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael's College. © Copyright by James E. Pedlar 2013 A Theology of Ecclesial Charisms With Special Reference to the Paulist Fathers and The Salvation Army James Edwin Pedlar Doctor of Philosophy in Theology University of St. Michael’s College 2013 ABSTRACT This project proposes a theology of “group charisms” and explores the implications of this concept for the question of the limits of legitimate diversity in the Church. The central claim of the essay is that a theology of ecclesial charisms can account for legitimately diverse specialized vocational movements in the Church, but it cannot account for a legitimate diversity of separated churches. The first major section of the argument presents a constructive theology of ecclesial charisms. The scriptural concept of charism is identified as referring to diverse vocational gifts of grace which are given to persons in the Church, and have an interdependent, provisional, and sacrificial character. Next, the relationship between charism and institution is specified as one of interdependence-in-distinction. Charisms are then identified as potentially giving rise to a multiplicity of diverse, vocationally-specialized movements in the Church, which are normatively distinguished from churches. The constructive argument concludes by claiming that the theology of ecclesial charisms as proposed supports visible, historic, organic unity. -

Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time July 11 2021

Fifteenth Sunday in ordinary time July 11 2021 WELCOME Mass AT THE CATH EDRAL Saturday, Jul 10 12:05pm Daily Mass Int. Fe Welton 4:30pm Sunday Vigil Mass † Norma Sidor Sunday, Jul 11 10:00am Sunday Mass (ASL interpretation) (televised / live-streamed) † Harriet V. Smith 12:00pm Misa Domingo en Español (live-streamed) † Maria Alejos Aranjibel 5:30pm Sunday Mass Intentions of CIC Collaborators and Partners in Mission 7:30pm Sunday Contemplative Mass Parish Family Monday, Jul 12 12:05pm Daily Mass † Ken Lomis Tuesday, Jul 13 12:05pm Daily Mass Int. Quentin Taylor Wednesday, Jul 14 12:05pm Daily Mass † Marjorie Dean Thursday, Jul 15 12:05pm Daily Mass † Janice Kosakoski Friday, Jul 16 12:05pm Daily Mass Int. Debbie Flinn Saturday, Jul 17 12:05pm Daily Mass † Richard Cebelak 4:30pm Sunday Vigil Mass † Betty Kersjes Sunday, Jul 18 10:00am Sunday Mass (ASL interpretation) (televised / live-streamed) † Don Jandernoa 12:00pm Misa Domingo en Español (live-streamed) † Pomposa Vazquez Altamirano 5:30pm Sunday Mass † Mary Schmuck 7:30pm Sunday Contemplative Mass Parish Family Confession Schedule God bless, Weekdays following the 12:05pm Mass Saturdays, 11-11:45am in the Chapel Very Rev. René Constanza, CSP (or by appointment) Rector Watch Sunday 10am Mass Online page 2 Go to grdiocese.org or the Cathedral’s Facebook page Scripture Reading... Sunday: Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Am 7:12-15 Ps 85:9-14 Casting a Net Eph 1:3-14 Mk 6:7-13 ome of us have bad memories of being the last one chosen for the kickball game during Monday: school recess. -

Seventh Sunday in Ordinary Time February 24, 2019

The Church of Saint Paul the Apostle Mother Church of the Paulist Fathers Mass Schedule ! Mass Schedule ! Saturday ··········· ! ZSUR+Q!WSSW.+!V'%'* ! Saturday ··········· !ZSUR+Q!WSSW.+!V'%'* ! Seventh Sunday in Sunday ·············· !ZSRR+Q!SRSRR+!C&-'0 ! Sunday! ·············· ZSRR+Q!SRSRR+!C&-'0! ! STSUR.+!S.,'1& ! STSUR.+!S.,'1& ! WSSW.+!Y-3,%!A"3*2 ! ! WSSW.+!Y-3,%!A"3*2 ! Ordinary Time Weekdays ········· YSUR+Q!STSSR.+ ! Weekdays! ········· YSUR+Q!STSSR.+ ! ! Reconciliation Hours February 24, 2019 Tuesdays & Thursdays····Reconciliation F-**-5',%!STSSR.+!M11 Hours ! TuesdaysSaturdays & ························· Thursdays ···· F-**-5',%!STSSR.+!M11VSRR! V!VSVW.+ ! ! ! V ! SaturdaysExposition ························· of Blessed VSRR! !VSVW.+ Sacrament Ash Wednesday ! ! Fridays ···························· F-**-5',%!YSUR+!M11 BenedictionExposition ····················· of BlessedSTSRR!N--, Sacrament! March 6, 2019 ! Fridays ···························· F-**-5',%!YSUR+!M11 ! ! Parish Information M11!S!&#"3*#S ! Parish Center & OfLices XSURAM ! ! VRW!W#12!W[2&!S20##2 ! ! ! N#5!Y-0)Q!NY!SRRS[! ! YSURAM ! Parish Center Hours STSSRPM M-,"7! V!T&301"7! !

Summer 2010 Paulist Fathers: Givinggiving the Gospel the a Voice Gospel Today a Voice Today Vol

Paulist Fathers Summer 2010 Paulist Fathers: GivingGiving the Gospel the a Voice Gospel Today a Voice Today Vol. 15 No. 3 WHAT’S AGENDA: New Paulist leadership sets the course .... 3 OFFICIAL: Many Paulists take new assignments .... 5 HAPPENING: PROMISE: Jay Duller becomes a Paulist ............... 4 BUSTED HALO: How to survive freshman year ........ 6 President’s Message Remembering two Paulists hythms. Cycles. Pendulum swings. RComing full circle. We use many expressions to speak of life’s growing and ebbing periods. We Paulists have our own rhythm, beginning not with birth, but by entering the community and dying. Recently we Paulists have experienced the deaths of two wonderful Paulists (I know, for many of us, that’s redundant!). Father Frank Diskin, then the oldest Paulist at 92, died in Courtesy Father Michael Kallock, CSP early July after a life Students at Old St. Mary’s School in Chicago pose for a group photo during the ground breaking ceremony for of robust pastoral a new school building. ministry at many of our foundations and then retirement. Thriving, not just surviving Within the same month, Father Larry Boadt lost in his battle against cancer Two Paulist foundations constructing new school buildings which he had suffered for more than a year. At 67, to many of us he seemed still By Stefani Manowski but building new school buildings. so young. Students at Old St. Mary’s School Both Frank and Larry represented It seems that more and more Catholic in Chicago will walk into their new different expressions of how we Paulists schools are closing their doors.