Why Animals Cannot Possess Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COURT of APPEALS of the STATE of NEW YORK ------X in the Matter of a Proceeding Under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus

COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------x In the Matter of a Proceeding under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on Index Nos. 162358/15 behalf of TOMMY, (New York County); Petitioner-Appellant, 150149/16 (New York -against- County) PATRICK C. LAVERY, individually and as an of Circle L Trailer Sales, Inc., DIANE LAVERY, and CIRCLE L TRAILER SALES, INC., Respondents-Respondents, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on behalf of KIKO, Petitioner-Appellant, -against- CARMEN PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., CHRISTIE E. PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., and THE PRIMATE SANCTUARY, INC., Respondents-Respondents. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------x MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR PERMISSION TO APPEAL TO THE COURT OF APPEALS Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Steven M. Wise, Esq. 5 Dunhill Road (of the Bar of the State of New Hyde Park, New York Massachusetts) 11040 By Permission of the Court (516) 747-4726 5195 NW 112th Terrace [email protected] Coral Springs, Florida 33076 (954) 648-9864 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Authorities ................................................................................... iv Argument .................................................................................................... 1 I. Preliminary Statement -

Bob Barker Farm to Fridge to the Rescue New Film Serves TV Legend Comes to Food for Thought the Aid of Calves Confronting Cafos Exclusive Interview with Dan Imhoff

- FREE - Go ahead, take it. Living Compassionate CTHE MAG OF MFA. SPRING-SUMMERL 11 ISSUE 8 Fishy Business MFA Goes Undercover at a Fish Slaughter Facility Bob Barker Farm to Fridge to the Rescue New Film Serves TV Legend Comes to Food for Thought the Aid of Calves Confronting CAFOs Exclusive Interview with Dan Imhoff MercyForAnimals.org dear friends newswatch Living Mark Bittman, columnist for The New York Times, recently wrote that “organizations like the Humane Society and Mercy For Animals need to be allowed to Heart-Healthy Vegetarian Diets Save Lives do the work that the federal and state governments Compassionate In February 2010, an article in Reuters warned that heart Luckily, this year, a new documentary has brought are not: documenting the kind of behavior most of us disease, caused primarily by excess meat consumption, this important message to the masses. Recounting the abhor. Indeed, the independent investigators should CL would kill 400,000 Americans that year. Researchers have journeys of Dr. Caldwell Esselstyn, known for successfully be supported.” Contributors been warning Americans for years that meaty diets are bad reversing heart disease through diet, and Dr. Colin Amy Bradley for the heart and that well-planned, plant-based diets help T. Campbell, author of The China Study, the most I couldn’t agree more. In fact, most people feel the Derek Coons protect against heart disease. In fact, William Castelli, M.D., comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted, same. A recent poll on the effort in Iowa to criminalize Forks Over Knives aims to save lives by showing Eddie Garza director of the Framingham Heart Study, the longest- undercover animal cruelty investigations found that running clinical study in medical history, says heart disease heart disease and other deadly diseases “can be Daniel Hauff a mere 21 percent of respondents supported the bills. -

Rattling the Cage Defended Steven M

Boston College Law Review Volume 43 Article 2 Issue 3 Number 3 5-1-2002 Rattling the Cage Defended Steven M. Wise Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Animal Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven M. Wise, Rattling the Cage Defended, 43 B.C.L. Rev. 623 (2002), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol43/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RATTLING THE CAGE DEFENDED STEVEN M. WISE* Abstract: In Rattling the Cage: Toward Levi Rights for Animals, the author advocated basic legal rights—specifically common law rights—for chimpanzees, bonobos, and other nonhuman animals. In this Article, the author responds to many of the major criticisms of Rattling the Cage. The author confronts critics of his historical arguments for legal rights for nonhuman animals, tracing those arguments through ancient philosophy and nineteenth century English statutes. The author also expands upon his legal arguments for animal rights, reexamining various theories of rights and justifications for treating animals as property, Finally, borrowing from his upcoming book Drawing the Line: Science and The Case for Animal Rights, the author defends his advocacy of legal rights for nonhuman animals based on the relative autonomy nonhuman animals possess. INTRODUCTION "The 'animal rights' movement is gathering steam and Steven Wise is one of the pistons."l Thus Judge Richard Posner began a Yale Law Journal review of my book, Rattling the Cage: Toward Legal Rights for Animals, published in 2000. -

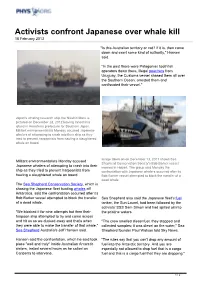

Activists Confront Japanese Over Whale Kill 18 February 2013

Activists confront Japanese over whale kill 18 February 2013 "Is this Australian territory or not? If it is, then come down and exert some kind of authority," Hansen said. "In the past there were Patagonian toothfish operators down there, illegal poachers from Uruguay, the Customs vessel chased them all over the Southern Ocean, arrested them and confiscated their vessel." Japan's whaling research ship the Nisshin Maru is pictured on December 28, 2012 leaving Innoshima island in Hiroshima prefecture for Southern Japan. Militant environmentalists Monday accused Japanese whalers of attempting to crash into their ship as they tried to prevent harpoonists from hauling a slaughtered whale on board. Image taken on on December 13, 2011 shows Sea Militant environmentalists Monday accused Shepherd Conservation Society's Bob Barker vessel Japanese whalers of attempting to crash into their moored in Hobart. The group said Monday the ship as they tried to prevent harpoonists from confrontation with Japanese whalers occurred after its hauling a slaughtered whale on board. Bob Barker vessel attempted to block the transfer of a dead whale. The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, which is chasing the Japanese fleet hunting whales off Antarctica, said the confrontation occurred after its Bob Barker vessel attempted to block the transfer Sea Shepherd also said the Japanese fleet's fuel of a dead whale. tanker, the Sun Laurel, had been followed by the activists' SSS Sam Simon and had spilled oil into "We blocked it for nine attempts but then their the pristine waters. harpoon ship attempted to try and come across and hit us so we ducked away and that's when "The crew smelled diesel fuel, they stopped and they were able to make the transfer of that whale," collected samples; it was diesel on the water," Sea Sea Shepherd Australia's Jeff Hansen said. -

Ealr, Volume 34, Number 3

Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review Volume 34 Number 3 Smart Brownfields Redevelopment for the 21st Century Symposium Articles Converting Brownfield Environmental Negatives into Energy Positives Steven Ferrey [pages 417–478] Abstract: There is a new paradigm for evaluating landfills. While landfills are contaminated repositories of hazardous wastes, they also are brown- fields that can be redeveloped for renewable energy development. It is possible to view landfills through a new lens: As endowed areas of renew- able energy potential that can be magnets for a host of renewable devel- opment incentives. Landfills also are critical resource areas for the con- trol of greenhouse gases. Landfill materials decompose into methane, a greenhouse gas that is more than twenty times more potent—molecule for molecule—than carbon dioxide. This Article traces the molecular composition of waste in landfills, analyzing the chemical stew that brews in these repositories. Without doubt, landfills in America are brownfields. And many of these landfills leak and cause public health risks. This Arti- cle also analyzes the potential to utilize landfill gas for electricity produc- tion or as a thermal resource. It evaluates the energy potential at munici- pal sewage treatment plants and the ability to utilize the land at landfills to host wind turbines. The environmental regulatory envelope that sur- rounds landfill operation is explored. Also analyzed are the various incen- tives that foster renewable energy development and are applicable to landfill brownfields development. These include tax credits, tax-pref- erenced financing, renewable energy credits under state renewable port- folio standard (RPS) systems in twenty-two states, and direct renewable trust fund subsidies in sixteen states, as well as net metering available in forty states. -

Framing Farming: Communication Strategies for Animal Rights Critical Animal Studies 2

Framing Farming: Communication Strategies for Animal Rights Critical Animal Studies 2 General Editors: Helena Pedersen, Stockholm University (Sweden) Vasile Stănescu, Mercer University (U.S.) Editorial Board: Stephen R.L. Clark, University of Liverpool (U.K.) Amy J. Fitzgerald, University of Windsor (Canada) Anthony J. Nocella, II, Hamline University (U.S.) John Sorenson, Brock University (Canada) Richard Twine, University of London and Edge Hill University (U.K.) Richard J. White, Sheffield Hallam University (U.K.) Framing Farming: Communication Strategies for Animal Rights Carrie P. Freeman Amsterdam - New York, NY 2014 Critical Animal Studies 2. Carrie P. Freeman, Framing Farming: Communication Strategies for Animal Rights. 1. Kim Socha, Women, Destruction, and the Avant-Garde. A Paradigm for Animal Liberation. This book is printed on recycled paper. Cover photo: Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals The paper on which this book is printed meets the requirements of “ISO 9706:1994, Information and documentation - Paper for documents - Requirements for permanence”. ISBN: 978-90-420-3892-9 E-Book ISBN: 978-94-012-1174-1 © Editions Rodopi B.V., Amsterdam – New York, NY 2014 Printed in The Netherlands Table of Contents List of Images 9 Foreword 11 Author’s perspective and background 11 Acknowledgements 14 Dedication 15 Chapter 1: Introduction 17 Themes and Theses in This Book 19 The Unique Contributions of This Book 20 Social Significance of Vegetarianism & Animal Rights 22 The Structure and Content of This Book 26 Word Choice 29 PART I OVERVIEW OF ANIMAL RIGHTS, VEGETARIANISM, AND COMMUNICATION Chapter 2: Ethical Views on Animals as Fellows & as Food 33 Development of Animal Activism in the United States 34 Western Thought on Other Animals 36 Western Vegetarian Ethics 43 Human Eating Habits 62 Chapter 3: Activist Communication Strategy & Debates 67 Communication and the Social Construction of Reality 68 Strategies for Social Movement Organizations 75 Ideological Framing Debates in U.S. -

Bob Barker Has Made a Huge Impact on Television, and on Animal Rights, Too

2015 LEGEND AWARD A Host and a Legend BOB BARKER HAS MADE A HUGE IMPACT ON TELEVISION, AND ON ANIMAL RIGHTS, TOO BY PATT f there were a Mt. Rushmore for television this name; you’re going to hear a lot about him.” When he landed as host MORRISON game show hosts, there’s no doubt about it: Bob Barker, for his part, said modestly that, “I feel like Barker would be up there. I’m hitting afer Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.” on “The Price is Right” Even without being made of granite, his face Barker went on to become a one-man Murderers’ has endured, flling Americans’ eyeballs and Row of game show hosts, making a long-lasting mark in 1972, he found his television screens for a remarkable half-century. He on “Truth or Consequences” and hosting a number of Ihelped to defne the game-show genre, as a pioneer in others that came and went. television home, the myriad ways, right down to taking the radical step of But when he landed as host on “Te Price is Right” letting his hair go naturally white for TV. He has nearly in 1972, he found his television home, the place where place where he broke 20 Emmys to his credit. he broke Johnny Carson’s 29-year record as longest- Johnny Carson’s 29-year Now, he is the recipient of the Legend Award from serving host of a TV show. the Los Angeles Press Club, presented at the 2015 It’s easy to rattle of numbers—for example, the frst record as longest-serving National Arts & Entertainment Awards. -

A Cultural Study of Gendered Onscreen

VEG-GENDERED: A CULTURAL STUDY OF GENDERED ONSCREEN REPRESENTATIONS OF FOOD AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR VEGANISM by Paulina Aguilera A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts & Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL August 2014 Copyright by Paulina Aguilera, 2014 11 VEG-GENDERED: A STUDY OF GENDERED ONSCREEN REPRESENTATIONS OF FOOD AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR VEGANISM by Paulina Aguilera This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor, Dr. Christine Scodari, School of Communication and Multimedia Studies, and has been approved by the members of her supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ~t~;,~ obe, Ph.D. David C. Williams, Ph.D. Interim Director, School of Communication and Multimedia Studies Heather Coltman, DMA Dean, ;~~of;candLetters 0'7/0 /:fdf4 8 ~T.Fioyd, Ed.D~ -D-at_e _ _,__ ______ Interim Dean, Graduate College 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to acknowledge Dr. Christi ne Scodari for her incredible guidance and immeasurable patience during the research and writing of this thesis. Acknowledgements are also in order to the participating committee members, Dr. Chris Robe and Dr. Fred Fejes, who provided further feedback and direction. Lastly, a special acknowledgement to Chandra Holst-Maldonado is necessary for her being an amazing source of moral support throughout the thesis process. -

Animals Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 1

AAnniimmaallss LLiibbeerraattiioonn PPhhiilloossoopphhyy aanndd PPoolliiccyy JJoouurrnnaall VVoolluummee 55,, IIssssuuee 11 -- 22000077 Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 1 2007 Edited By: Steven Best, Chief Editor ____________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Steven Best, Chief Editor Pg. 2-3 Introducing Critical Animal Studies Steven Best, Anthony J. Nocella II, Richard Kahn, Carol Gigliotti, and Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 4-5 Extrinsic and Intrinsic Arguments: Strategies for Promoting Animal Rights Katherine Perlo Pg. 6-19 Animal Rights Law: Fundamentalism versus Pragmatism David Sztybel Pg. 20-54 Unmasking the Animal Liberation Front Using Critical Pedagogy: Seeing the ALF for Who They Really Are Anthony J. Nocella II Pg. 55-64 The Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act: New, Improved, and ACLU-Approved Steven Best Pg. 65-81 BOOK REVIEWS _________________ In Defense of Animals: The Second Wave, by Peter Singer ed. (2005) Reviewed by Matthew Calarco Pg. 82-87 Dominion: The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy, by Matthew Scully (2003) Reviewed by Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 88-91 Terrorists or Freedom Fighters?: Reflections on the Liberation of Animals, by Steven Best and Anthony J. Nocella, II, eds. (2004) Reviewed by Lauren E. Eastwood Pg. 92 Introduction Welcome to the sixth issue of our journal. You’ll first notice that our journal and site has undergone a name change. The Center on Animal Liberation Affairs is now the Institute for Critical Animal Studies, and the Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal is now the Journal for Critical Animal Studies. The name changes, decided through discussion among our board members, were prompted by both philosophical and pragmatic motivations. -

Volume 21, No. 2 Fall 2010 ______

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR ENVIRONMENTAL ETHICS NEWSLETTER _____________________________________________________ Volume 21, No. 2 Fall 2010 _____________________________________________________ GENERAL ANNOUNCEMENTS ISEE Membership: ISEE membership dues are now due annually by Earth Day—22 April—of each year. Please pay your 2010-2011 dues now if you have not already done so. You can either use the form on the last page of this Newsletter to mail a check to ISEE Treasurer Marion Hourdequin, or you can use PayPal with a credit card from the membership page of the ISEE website at: <http://www.cep.unt.edu/iseememb.html>. “Old World and New World Perspectives on Environmental Philosophy,” Eighth Annual Meeting of the International Society for Environmental Ethics (ISEE), Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 14-17 June 2011: Please see the full call for abstracts and conference details in the section CONFERENCES AND CALLS below. Abstracts are due by 6 December 2010. ISEE Newsletter Going Exclusively Electronic: Starting with the Spring 2011 issue (Volume 22, no. 1), hardcopies of the ISEE Newsletter will no longer be produced and mailed to ISEE members via snail mail. ISEE members will continue to receive the Newsletter electronically as a pdf and, of course, can print their own hardcopies. New ISEE Newsletter Editor: Starting with the Spring 2011 issue, the new ISEE Newsletter Editor will be William Grove-Fanning. Please submit all ISEE Newsletter items to him at: <[email protected]>. Welcome William! ISEE Newsletter Issues: There was no 2010 Spring/Summer issue of the ISEE Newsletter. Because of the ISEE Newsletter Editor transition from Mark Woods to William Grove-Fanning, there will be no Winter 2011 issue of the ISEE Newsletter. -

Bovine Benefactories: an Examination of the Role of Religion in Cow Sanctuaries Across the United States

BOVINE BENEFACTORIES: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ROLE OF RELIGION IN COW SANCTUARIES ACROSS THE UNITED STATES _______________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ________________________________________________________________ by Thomas Hellmuth Berendt August, 2018 Examing Committee Members: Sydney White, Advisory Chair, TU Department of Religion Terry Rey, TU Department of Religion Laura Levitt, TU Department of Religion Tom Waidzunas, External Member, TU Deparment of Sociology ABSTRACT This study examines the growing phenomenon to protect the bovine in the United States and will question to what extent religion plays a role in the formation of bovine sanctuaries. My research has unearthed that there are approximately 454 animal sanctuaries in the United States, of which 146 are dedicated to farm animals. However, of this 166 only 4 are dedicated to pigs, while 17 are specifically dedicated to the bovine. Furthermore, another 50, though not specifically dedicated to cows, do use the cow as the main symbol for their logo. Therefore the bovine is seemingly more represented and protected than any other farm animal in sanctuaries across the United States. The question is why the bovine, and how much has religion played a role in elevating this particular animal above all others. Furthermore, what constitutes a sanctuary? Does -

Legal Research Paper Series

Legal Research Paper Series NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY By Rita K. Lomio and J. Paul Lomio Research Paper No. 6 October 2005 Robert Crown Law Library Crown Quadrangle Stanford, California 94305-8612 NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRPAHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY I. Books II. Reports III. Law Review Articles IV. Newspaper Articles (including legal newspapers) V. Sound Recordings and Films VI. Web Resources I. Books RESEARCH GUIDES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES Hoffman, Piper, and the Harvard Student Animal Legal Defense Fund The Guide to Animal Law Resources Hollis, New Hampshire: Puritan Press, 1999 Reference KF 3841 G85 “As law students, we have found that although more resources are available and more people are involved that the case just a few years ago, locating the resource or the person we need in a particular situation remains difficult. The Guide to Animal Law Resources represents our attempt to collect in one place some of the resources a legal professional, law professor or law student might want and have a hard time finding.” Guide includes citations to organizations and internships, animal law court cases, a bibliography, law schools where animal law courses are taught, Internet resources, conferences and lawyers devoted to the cause. The International Institute for Animal Law A Bibliography of Animal Law Resources Chicago, Illinois: The International Institute for Animal Law, 2001 KF 3841 A1 B53 Kistler, John M. Animal Rights: A Subject Guide, Bibliography, and Internet Companion Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000 HV 4708 K57 Bibliography divided into six subject areas: Animal Rights: General Works, Animal Natures, Fatal Uses of Animals, Nonfatal Uses of Animals, Animal Populations, and Animal Speculations.