Arxiv:1509.00722V3 [Cond-Mat.Mtrl-Sci] 6 Nov 2015 Surface of the Atomic Positions, This Thorough Study Generated 21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of Sulfur to Oxygen*

OpenStax-CNX module: m34977 1 Comparison of Sulfur to Oxygen* Andrew R. Barron This work is produced by OpenStax-CNX and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 1 Size Table 1 summarizes the comparative sizes of oxygen and sulfur. Element Atomic radius Covalent radius Ionic radius (Å) van der Waal ra- (Å) (Å) dius (Å) Oxygen 0.48 0.66 1.40 1.52 Sulfur 0.88 1.05 1.84 1.80 Table 1: Comparison of physical characteristics for oxygen and sulfur. 2 Electronegativity Sulfur is less electronegative than oxygen (2.4 and 3.5, respectively) and as a consequence bonds to sulfur are less polar than the corresponding bonds to oxygen. One signicant result in that with a less polar S-H bond the subsequent hydrogen bonding is weaker than observed with O-H analogs. A further consequence of the lower electronegativity is that the S-O bond is polar. 3 Bonds formed Sulfur forms a range of bonding types. As with oxygen the -2 oxidation state prevalent. For example, sulfur forms analogs of ethers, i.e., thioethers R-S-R. However, unlike oxygen, sulfur can form more than two covalent (non-dative) bonds, i.e., in compounds such as SF4 and SF6. Such hypervalent compounds were originally thought be due to the inclusion of low energy d orbitals 3 2 in hybrids (e.g., sp d for SF6); however, a better picture involves a combination of s and p ortbitals in bonding (Figure 1). Any involvement of the d orbitals is limited to the polarization of the p orbitals rather than direct hydridization. -

Effect of Catenation and Basicity of Pillared Ligand on the Water Stability of Mofs

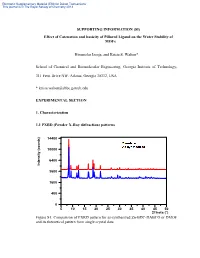

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Dalton Transactions This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2013 SUPPORTING INFORMATION (SI) Effect of Catenation and basicity of Pillared Ligand on the Water Stability of MOFs Himanshu Jasuja, and Krista S. Walton* School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, 311 Ferst Drive NW, Atlanta, Georgia 30332, USA * [email protected] EXPERIMENTAL SECTION 1. Characterization 1.1 PXRD (Powder X-Ray diffraction) patterns 14400 10000 6400 Intensity (counts) Intensity 3600 1600 400 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 2Theta (°) Figure S1: Comparison of PXRD pattern for as-synthesized Zn-BDC-DABCO or DMOF and its theoretical pattern from single crystal data Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Dalton Transactions This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2013 14400 10000 6400 Intensity (counts) Intensity 3600 1600 400 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 2Theta (°) Figure S2: Comparison of PXRD pattern for as-synthesized Zn-BDC-BPY or MOF-508a and its theoretical pattern from single crystal data 14400 10000 6400 Intensity (counts) Intensity 3600 1600 400 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 2Theta (°) Figure S3: Comparison of PXRD pattern for as-synthesized Zn-TMBDC-DABCO or DMOF-TM and its theoretical pattern from single crystal data Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Dalton Transactions This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2013 14400 10000 6400 Intensity (counts) Intensity 3600 1600 400 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 2Theta (°) Figure S4: Comparison of PXRD pattern for as-synthesized Zn-TMBDC-BPY or MOF- 508-TM and its theoretical pattern from single crystal data 6400 3600 Intensity (counts) Intensity 1600 400 0 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 2Theta (°) Figure S5: PXRD patterns for as-synthesized Zn-BDC-BPY or MOF-508a and activated Zn-BDC-BPY or MOF-508b displaying shifting of peaks towards right on activation which was also observed by Chen et. -

Chemistry Study Materials for Class 10 (NCERT Based: Questions with Answers) Ganesh Kumar Date:- 28/07/2020

Chemistry Study Materials for Class 10 (NCERT Based: Questions with Answers) Ganesh Kumar Date:- 28/07/2020 74. How much carbon is present on earth and CO2 in atmosphere? Answer: 0.02%, 0.03% 75. What is valency of carbon? Answer: 4 76. Why does carbon form strong bonds? Answer: It is due to small size. 77. What will be the product formed when carbon is burnt in presence of air? Answer: Carbon dioxide 78. What is Allotropy? Answer: It is a property due to which an element can exist in more than one form which differ in physical properties but have similar chemical properties, e.g., carbon, sulphur, phosphorus, oxygen show allotropy. 79. Name three allotropes of carbon. Answer: Diamond, graphite and Buckminster fullerenes 80. Which is the purest allotrope of carbon? Answer: Buckminster fullerenes. 81. Why is graphite soft and slippery? Answer: Due to weak vander Waals’ forces of attraction between hexagonal layers. 82. Why is diamond hard? Answer: It is due to strong covalent bonds. 83. Why is diamond lustrous? Answer: It is due to high refractive index. 84. Carbon has four electrons in its valence shell. How does carbon attain stable electronic configuration. Answer: By sharing four electrons with other atoms. 85. Why is carbon tetravalent? Answer: It is because carbon can share form electrons to complete its octet. 86. Which gas is present in LPG? Answer: Butane and Isobutane 87. Which element exhibits the property of catenation to maximum extent and why? Answer: Carbon shows catenation to maximum extent because it forms strong covalent bonds. -

Group 13 Elements

GROUP I5 ELEMENTS Q. 1. Give chemical reaction in support of the statement that all the bonds in PCI5 molecule are not equivalent. Ans. Due to greater bond pair-bond pair repulsions, the two axial P — Cl bonds are less stable than the three equatorial P — Cl bonds. It is because of this reason that when PC15 is heated, the less stable axial bonds are Broken to form Cl2. Δ PCl5 -------------- PCl3 + Cl2. Q. 2. The tendency for catenation decreases down the group 14. Or Why carbon shows catenation but silicon does not Ans. As we move down the group 14, the atomic size increases and hence the strength of M—M bond decreases steadily. Consequently the tendency for catenation decreases down the group. Q. 3. PCI5 is known but NC15 is not known. Explain. 2 2 6 2 1 1 1 Ans. Electronic configuration of P is 1s 2s 2p 3s 3px 3py 3pz . Thus phosphorus has empty 3d orbitals in which the elecron of the 3s-orbital can be excited but nitrogen has no d-orbitals as its electronic configuration is 2 2 1 1 1 1s 2s 2px 2py 2pz . Q. 4. Why molecular nitrogen is not reactive ? Ans. The bond dissociation energy for the triple bond in N = N is very high because of small size of N-atoms and hence small internuclear distance. Q.5. H3PO3 is diprotic (or)dibasic. Why? Ans. Since it has only two ionisable H – atoms which are present as OH groups. Q. 6. Nitrogen exists as diatomic molecule, N2, whereas phosphorus exists a tetratomic molecule P4. -

Unit 12 Carbon Akd Its Compounds

UNIT 12 CARBON AKD ITS COMPOUNDS Structure 12.1 Introduction 12.2 Objectives 12.3 Allotropes of Carbon 12.4 Why are there a Large Number of Carbon Compounds in Nature 12.4.1 Catenation 12.4.2 Isomerism 12.5 Hydrocarbons 12.5.1 Saturated Hydrocarbons 12.5.2 Unsaturated Hydrocarbons 12.5.3 Homologous Hydrocarbons 12.5.4 Aromatic Hydrocarbons 12.6 Some other Organic Compounds 12.6.1 Hydrocarbon as Parent Compound 12.6.2 Functional Groups 12.6.3 Alcohols 12.6.4 Carboxylic Acids 12.6.5 Esters 12.7 Man Made Materials from Carbon Compounds 12.7.1 Polymers-Fibres, Plastics, Rubbers 12.7.2 Soaps and Detergents 12.8 Let Us Sum Up 12.9 Unit-end Exercises 12.10 Answers to Check Your Progress 12.11 Suggested Readings 12.1 INTRODUCTION In the previous unit you have studied about the strategies of teaching about some metallic and non-metallic elements and some of their compounds. In the present unit we shall discuss the teaching of some exemplary concepts and subtopics related to carbon and its compounds. Here it is important to appreciate that carbon and organic compounds need to be dealt as separate from other elements and their compounds. As you go through this unit you would be familiarizing yourself with teaching of allotropic forms of carbon, hydrocarbons and other compounds of carbon and finally the man made materials obtained from carbon compounds. This unit shows us that living bodies and their products contain a large quantity of carbon compounds in our daily life. -

2. Allotropy in Carbon the Property Due to Which an Element Exists In

SUBJECT-CHEMISTRY DATE- 22/11/2020 CLASS- X TOPICS- Chap. 4 Carbon and its Compounds Carbon is one of the most essential components of living organisms. There are two stable isotopes of carbon C-12 and C-13. After these two one more isotope of carbon is present C-14. Carbon is used for radiocarbon dating One of the most amazing properties of carbon is its ability to make long carbon chains and rings. This property of carbon is known as catenation. Carbon has many special abilities out of all one unique ability is that carbon forms double or triple bonds with itself and with other electronegative atoms like oxygen and nitrogen. These two properties of carbon i.e catenation and multiple bond formation, it has the number of allotropic forms. Allotrope is nothing but the existence of an element in many forms which will have different physical property but will have similar chemical properties and its forms are called allotropes of allotropic forms. Allotropes are defined as the two or more physical forms of one element. These allotropes are all based on carbon atoms but exhibit different physical properties, especially with regard to hardness. The two common, crystalline allotropes of carbon are diamond and graphite. Carbon shows allotropy because it exists in different forms of carbon. Though these allotropes of carbon have a different crystal structure and different physical properties, their chemical properties are the same and show similar chemical properties. Both diamond and graphite have symbol C. Both give off carbon dioxide when strongly heated in the presence of oxygen. -

Inorganic Chemistry

INORGANIC CHEMISTRY Silicones and Phosphazenes Prof. Ranjit K. Verma University Department of Chemistry Magadh University Bodh Gaya-824234 (31.07.2006) CONTENTS Introduction Silicones General introduction Structural features and synthesis Interesting properties and uses Phosphazenes General introduction Nature of bonding in triphosphazenes Uses Keywords Polymers, catenation, silicones, halosilanes, silicone oils, silicone elastomers, silicone resins, phosphazenes, diphosphazenes, polyphosphazenes, bonding in triphosphazenes, homorphic and heteromorphic interactions 1 Introduction Polymers have revolutionized human civilization. Carbon forms polymers most extensively on account of its unparalleled catenation property (tendency to form chains). Although to a limited extent, catenation is exhibited by some other elements in Group 14 and Group 15. For example, in Group 14, the catenation tendency follows the sequence C >> Si > Ge ~ Sn >>Pb. In Group 15, the NN single bond is so weak that its chain length does not go beyond 3 (in N3ion). The chain length in case of phosphorus is up to 2 (e.g. in P2H4). Silicon in Group 14 forms polymeric silanes with difficulty. In conjugation with oxygen however, it makes extensive SiOSi linkages forming silicones. Similarly, in conjugation with nitrogen, phosphorus shows unique capability of forming extensive — N = P — bonds in what are called phosphazenes. These two classes of polymers established Si and P as the second and the third most extensively polymer- forming elements, respectively and, have revolutionized polymer science on account of their oxidative, thermal and radiation stabilities. The C = C and C – H bonds in C-based polymers are susceptible to oxidation and the C-C bonds are prone to cleavage, but these two classes of silicones and phosphazenes are free from these lacunae. -

Executive Summaries for the Hydrogen Storage Materials Centers of Excellence

Executive Summaries for the Hydrogen Storage Materials Centers of Excellence Chemical Hydrogen Storage CoE, Hydrogen Sorption CoE, and Metal Hydride CoE Period of Performance: 2005-2010 Fuel Cell Technologies Program Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy U. S. Department of Energy April 2012 2 Primary Authors: Chemical Hydrogen Storage (CHSCoE): Kevin Ott, Los Alamos National Laboratory Hydrogen Sorption (HSCoE): Lin Simpson, National Renewable Energy Laboratory Metal Hydride (MHCoE): Lennie Klebanoff, Sandia National Laboratory Contributors include members of the three Materials Centers of Excellence and the Department of Energy Hydrogen Storage Team in the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy’s Fuel Cell Technologies Program. 3 Contents Introduction and Background 5 Executive Summary of the CHCoE 7 Executive Summary of the HSCoE 37 Executive Summary of the MHCoE 55 4 Introduction and Background The use of hydrogen and fuel cells to power light-duty vehicles offers an effective pathway as part of a portfolio of technologies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and petroleum usage.1 In addition to the challenges associated with improving the power density and durability of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells while reducing their costs, there are challenges in developing hydrogen storage technologies that offer high specific energy and energy density at acceptable costs for use onboard vehicles.2 Working with the U.S. automotive manufacturers through the FreedomCAR and Fuel Partnership (now U.S. DRIVE), the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) established in 2003 a comprehensive set of performance metrics for onboard hydrogen storage systems based on comparison with gasoline fueled vehicles. The metrics included 2015 system-level targets for specific energy and energy density of 3.0 kWh/kg (9 wt.%) and 3 2.7 kWh/L (81 g H2/L) respectively. -

Recq Helicase Stimulates Both DNA Catenation and Changes in DNA Topology by Topoisomerase III*

THE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY Vol. 278, No. 43, Issue of October 24, pp. 42668–42678, 2003 © 2003 by The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Inc. Printed in U.S.A. RecQ Helicase Stimulates Both DNA Catenation and Changes in DNA Topology by Topoisomerase III* Received for publication, March 24, 2003, and in revised form, June 10, 2003 Published, JBC Papers in Press, August 8, 2003, DOI 10.1074/jbc.M302994200 Frank G. Harmon‡, Joel P. Brockman, and Stephen C. Kowalczykowski§ From the Division of Biological Sciences, Sections of Microbiology and of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Center for Genetics and Development, University of California, Davis, California 95616 Together, RecQ helicase and topoisomerase III (Topo which is premature aging and a predisposition to cancer (10). III) of Escherichia coli comprise a potent DNA strand Loss of BLM helicase function results in Bloom’s syndrome; in passage activity that can catenate covalently closed this case, afflicted individuals are highly susceptible to certain DNA (Harmon, F. G., DiGate, R. J., and Kowalczykowski, types of cancer (15). Mutations in the RECQ4 helicase are S. C. (1999) Mol. Cell 3, 611–620). Here we directly as- found in a subset of Rothmund-Thompson syndrome cases, a sessed the structure of the catenated DNA species disease that is also typified by a predisposition to malignancy formed by RecQ helicase and Topo III using atomic force (12, 18). microscopy. The images show complex catenated DNA Phenotypic analysis indicates that these helicases are species involving crossovers between multiple double- needed in their respective organisms to maintain the stability stranded DNA molecules that are consistent with full of the genome (for review, see Ref. -

Organosilicon Reagents in Natural Product Synthesis

GENERAL I ARTICLE Organosilicon Reagents in Natural Product Synthesis Hari Prasad Berzelius, the Swedish chemist in 1807 introduced the term 'organic compounds' as those substances derived from once living organisms (organized systems). Carbon exhibits the property of catenation (formation of chains) and forms a plethora of compounds on earth. Silicon on the other hand which is placed below carbon in the periodic table does not Hari Prasad S teaches exhibit this property. This article is a brief account of some post graduate students of the several reagents and classes of compounds encoun medicinal organic tered in organosilicon chemistry. chemistry and organic spectroscopy at the Introduction Chemistry Department, Central College, Banga Silicon is the second most abundant element on the surface of lore University, Banga the earth, after oxygen. It is the mildest of metals. Silicon does lore. His research includes synthetic and not occur free in nature, but is found as silica (quartz, sand) or as mechanistic organic silicates (feldspar, kaolinite), etc. In the periodic table, it be chemistry. longs to group 14, and is placed below carbon. It has atomic number 14 and comprises three isotopes 28 (92.18%), 29 (4.17%) and 30 (3.11 %). Industrially, silicon is prepared by the carbon reduction of silica in an electric arc furnace. Si02 + 2C ---..~ Si +2CO Silicon is purified by the zone melting method of refining. Organosilicon Based Reagents Organosilicon compounds do not occur free in nature, and are prepared synthetically. The property of catenation (formation of alkanes, alkenes, alkynes, etc.) observed in carbon chemistry is absent in silicon chemistry. -

Chemistry of Sulfur (Z=16) Learning Objectives Describe the Chemistry of the Oxygen Group

Chemistry of Sulfur (Z=16) Learning Objectives Describe the chemistry of the oxygen group. Give the trend of various properties. Remember the names of Group 16 elements. Explain the Frasch process. Describe properties and applications of H2SO4 . Explain properties and applications of H2S. Sulfur is a chemical element that is represented with the chemical symbol "S" and the atomic number 16 on the periodic table. Because it is 0.0384% of the Earth's crust, sulfur is the seventeenth most abundant element following strontium. Sulfur also takes on many forms, which include elemental sulfur, organo-sulfur compounds in oil and coal, H2S(g) in natural gas, and mineral sulfides and sulfates. This element is extracted by using the Frasch process (discussed below), a method where superheated water and compressed air is used to draw liquid sulfur to the surface. Offshore sites, Texas, and Louisiana are the primary sites that yield extensive amounts of elemental sulfur. However, elemental sulfur can also be produced by reducing H2S, commonly found in oil and natural gas. For the most part though, sulfur is used to produce SO2(g) and H2SO4. Known from ancient times (mentioned in the Hebrew scriptures as brimstone) sulfur was classified as an element in 1777 by Lavoisier. Pure sulfur is tasteless and odorless with a light yellow color. Samples of sulfur often encountered in the lab have a noticeable odor. Sulfur is the tenth most abundant element in the known universe. Sulfur at a Glance Atomic Number 16 Atomic Symbol S Atomic Weight 32.07 grams per mole Structure orthorhombic Phase at room temperature solid Classification nonmetal Physical Properties of Sulfur Sulfur has an atomic weight of 32.066 grams per mole and is part of group 16, the oxygen family. -

ORGANIC CHEMISTRY Organic Chemistry Is Often Described As the Chemistry of Carbon-Based Compounds That Consist Primarily of Carbon and Hydrogen

ORGANIC CHEMISTRY Organic chemistry is often described as the chemistry of carbon-based compounds that consist primarily of carbon and hydrogen. The unique chemistry of carbon • Carbon atoms have the ability to form four strong covalent bonds • Carbon undergoes a process known as hybridization which produces four available bonding sites ( see “process of hybridization”) • Carbon atoms bond with other carbon atoms to form chains or ring structures. This is called catenation These chains can be thousands of atoms long. • Carbon has the ability to make single, double and triple bonds with itself Catenation is described as the ability of carbon atoms to bond with themselves to form chain or ring structures The process of hybridisation A carbon atom in the ground state: C A carbon atom in the “excited” state: 4 x sp3 hyhrid sub-orbitals able to accept one electron each A process called orbital mixing now occurs where the 2s and 2p orbital’s now mix together to produce four sub-orbitals of equal energy. There sub- orbitals are known as sp3 hybrid orbital’s and it is these hybrid orbital’s that provide the four available bonding sites Classification of organic compounds THE HYDROCARBONS……are organic compounds containing carbon and hydrogen only H H H Alkanes H C H H C C H H H H Saturated compound – compounds in which all bonds between the carbon atoms are single bonds. H H Alkenes H C C H Unsaturated compound – compounds in which there is at least one double and/or triple bond between carbon atoms. Homologous Series and Functional groups Alkanes CnH2n+2 H H H H H H H H H H C C H H C C C H H C C C C H H H H H H H H H H C H C2H6 C3H8 4 10 Alkenes CnH2n H H H H H H H H H H C C C C H H C C H H C C C H C H H H C2H4 3 6 H C4H8 Homologous Series and Functional Groups Functional group - a bond, atom or group of atoms that form the centre of chemical activity in the organic compound.