JUN 1 9 1984 Archive$

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aesthetics in Ruins: Parisian Writing, Photography and Art, 1851-1892

Aesthetics in Ruins: Parisian Writing, Photography and Art, 1851-1892 Ioana Alexandra Tranca Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Trinity College March 2017 I would like to dedicate this thesis to my parents, Mihaela and Alexandru Declaration I hereby declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. This dissertation does not exceed the prescribed word limit of 80000, excluding bibliography. Alexandra Tranca March 2017 Acknowledgements My heartfelt gratitude goes to my Supervisor, Dr Nicholas White, for his continued advice and support throughout my academic journey, for guiding and helping me find my way in this project. I also wish to thank Dr Jean Khalfa for his insights and sound advice, as well as Prof. Alison Finch, Prof. Robert Lethbridge, Dr Jann Matlock, and Prof. -

Vincent De Paul

SAINT VINCENT DE PAUL CORRESPONDENCE VOLUME I Reproduction of a painting which had once belonged to Queen Anne of Austria and then to the Hotel des Invalides. It is now in the possession of the Motherhouse of the Priests of the Mission, of Saint 95 rue de Sevres, Paris. In the opinion of experts, this portrait was painted in the time Vincent de Paul by an artist who had the Saint before him. SAINT VINCENT DE PAUL CORRESPONDENCE CONFERENCES, DOCUMENTS I CORRESPONDENCE VOLUME I (1607 - 1639) NEWLY TRANSLATED, EDITED, AND ANNOTATED FROM THE 1920 EDITION OF PIERRE COSTE, C.M. TO VERY REVEREND JAMES W. RICHARDSON, C.M. WHO AS SUPERIOR GENERAL OF THE CONGREGATION OF THE MISSION AND OF THE COMPANY OF THE DAUGHTERS OF CHARITY INITIATED AND ENCOURAGED THIS WORK VI Edited by: SR. JACQUELINE KILAR, D.C Translated by: SR. HELEN MARIE LAW, D.C. SR. JOHN MARIE POOLE, D.C. REV. JAMES R. KING, C.M. REV. FRANCIS GERMOVNIK, C.M. (Latin) Annotated by: REV. JOHN W. CARVEN, C.M. NIHIL OBSTAT Rev. John A. Grindel, C.M Censor Deputatus IMPRIMATUR Rev. Msgr. John F. Donoghue Vicar Generalfor the Archdiocese of Washington May 25, 1983 © 1985, Vincentian Conference, U.S.A. Published in the United States by New City Press 206 Skillman Avenue, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11211 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 83-063559 ISBN 0-911782-50-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface to the English Translation xix Letter of Father Verdier xxiii Introduction to the French Edition xxv Introduction to the English Edition xlix 1. -

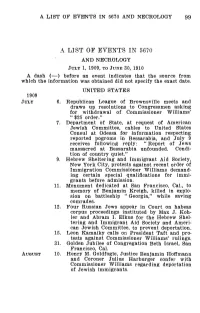

A List of Events in 5670 and Necrology 99

A LIST OF EVENTS IN 5670 AND NECROLOGY 99 A LIST OF EVENTS IN 5670 AND NECROLOGY JULY 1, 1909, TO JUNE 30, 1910 A dash (—) before an event indicates that the source from which the information was obtained did not specify the exact date. UNITED STATES 1909 JULY 6. Republican League of Brownsville meets and draws up resolutions to Congressmen asking for withdrawal of Commissioner Williams' " $25 order." 7. Department of State, at request of American Jewish Committee, cables to United States Consul at Odessa for information respecting reported pogroms in Bessarabia, and July 9 receives following reply: "Report of Jews massacred at Bessarabia unfounded. Condi- tion of country quiet." 9. Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society, New York City, protests against recent order of Immigration Commissioner Williams demand- ing certain special qualifications for immi- grants before admission. 11. Monument dedicated at San Francisco, Cal., to memory of Benjamin Kreigh, killed in explo- sion on battleship " Georgia," while saving comrades. 12. Four Russian Jews appear in Court on habeas corpus proceedings instituted by Max J. Koh- ler and Abram I. Elkus for the Hebrew Shel- tering and Immigrant Aid Society and Ameri- can Jewish Committee, to prevent deportation. 15. Leon Kamaiky calls on President Taft and pro- tests against Commissioner Williams' rulings. 31. Golden Jubilee of Congregation Beth Israel, San Francisco, Cal. AUGUST 10. Henry M. Goldfogle, Justice Benjamin Hoffmann and Coroner Julius Harburger confer with Commissioner Williams regarding deportation of Jewish immigrants. 100 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK 13. Several Grand Masters of Jewish Orders meet in conference with Congressmen Goldfogle and Sabath and decide to ask Secretary Nagle for a conference. -

Final Market Analysis D2.4

FP7-SMARTCITIES-2013(ICT) Objective ICT-2013.6.2 Data Centres in an energy-efficient and environmentally friendly Internet DC4Cities An environmentally sustainable data centre for Smart Cities Project Nº 609304 Final Market Analysis D2.4 Responsible: Sonja Klingert [UNIMA] Contributors: Sonja Klingert, Thomas Schulze, Torben Möller, Nicole Wesemeyer [UNIMA]; Wolfgang Duschl, Florian Niedermeier, Hermann de Meer [UNIPASSAU]; Federico Lombart Badal, Francesc Casaus, Eduard Martín [IMI]; Silvia Sanjoaquin Vives, Elena Alonso Pantoja, Gonzalo Jose Diaz Velez [GN]; Mehdi Sheikhalishahi [CREATE-NET]; Frederic Wauters, Maria Perez Ortega, [FM]; Marta Chinnici [ENEA] Document Reference: D2.4 – Final Market Analysis Dissemination Level: PU Version: 3.0 Date: 30 Nov 2015 Project Nº 609304 D2.4 – Final Market Analysis 29.11.2015 DC4Cities EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The final market analysis, D2.4, builds on the findings of the first market analysis, D2.2, where regions in Europe offering good starting conditions for marketing a DC4Cities based tool were identified. Now, for the second stage of the analysis, the plan was to evaluate these findings for specific cities, which at the same time play a major role in the data centre industry and are among the most advanced smart cities in Europe. The analysis therefore included Barcelona, as DC4Cities partner, and the data centre “Big Five” cities in Europe: London, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Paris, and Madrid. The results partly reinforced the conclusions of the first market analysis, but some findings also came as a surprise once urban agglomerations were analysed in more detail: The most thorough analysis could be executed for Barcelona, due to a good data basis as Barcelona partners belong to the consortium of DC4Cities. -

Grace Phelan Final/Diss

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ ANTOINE FRANÇOIS MOMORO “First Printer of National Liberty” 1756-1794 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Grace M. Phelan September 2015 The Dissertation of Grace M. Phelan is approved: _______________________________ Professor Jonathan Beecher, Chair _______________________________ Professor Mark Traugott _______________________________ Professor Marilyn Westerkamp ___________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Grace M. Phelan 2015 Table of Contents List of Illustrations iv Acknowledgments viii Introduction 1 1. From Besançon to Paris: Momoro's transition from Old Regime libraire to "First Printer of National Liberty" 14 2. Momoro's Political Ascendancy in Sectional Politics 84 3. Traité Elémentaire de l'Imprimerie: Conservative Instruction from the "First Printer of National Liberty" 177 4. Letters from the Vendée: Momoro's Narrative of Revolution and Counter- Revolution 252 Epilogue 321 Appendix A: Books Sold by Momoro, 1788-1790 325 Appendix B: Momoro's Publications, 1789-1793 338 Archival Sources 356 Works Cited 357 iii List of Illustrations 1. Premier Imprimeur de la Liberté Nationale 53 2. Second portrait of Momoro by Peronard 54 iv ABSTRACT Grace M. Phelan ANTOINE FRANCOIS MOMORO: "First Printer of National Liberty" 1756-1794 Antoine François Momoro (1756-1794) appears in historiographies of the French Revolution, in the history of printing and typography and in the history of work during the eighteenth century. Historians of the 1789 Revolution have often defined Momoro as either a sans-culottes or spokesman for the sans-culottes. Marxist historians and thinkers defined Momoro as an early socialist thinker for his controversial views on price fixing and private property. -

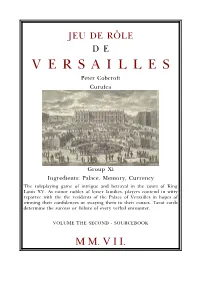

V E R S a I L L E S

JEU DE RÔLE D E V E R S A I L L E S Peter Cobcroft Curufea Group Xi Ingredients: Palace, Memory, Currency The roleplaying game of intrigue and betrayal in the court of King Louis XV. As minor nobles of lesser families, players contend in witty repartee with the the residents of the Palace of Versailles in hopes of winning their confidences or swaying them to their causes. Tarot cards determine the success or failure of every verbal encounter. VOLUME THE SECOND - SOURCEBOOK M M. V I I. Contents Life in 18th Century France....................................... 3 Early life and accession..................................... 21 Events.............................................................................. 3 Louis's reaction to the Revolution.................... 22 Talk at the Court................................................. 3 Attempt to flee the country...............................22 News..................................................................... 3 Condemnation to death..................................... 23 Wars..................................................................... 3 Marie-Antoinette ................................................ 23 Religion................................................................ 3 Duke of Orléans, Philippe II............................. 24 Literature............................................................. 4 The King's Mistresses.................................................... 25 Timeline of Inventions.................................................... 5 Comtesse -

Aesthetics in Ruins: Parisian Writing, Photography and Art, 1851-1892

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Aesthetics in Ruins: Parisian Writing, Photography and Art, 1851-1892 Ioana Alexandra Tranca Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Trinity College March 2017 I would like to dedicate this thesis to my parents, Mihaela and Alexandru Declaration I hereby declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. This dissertation does not exceed the prescribed word limit of 80000, excluding bibliography. Alexandra Tranca March 2017 Acknowledgements My heartfelt gratitude goes to my Supervisor, Dr Nicholas White, for his continued advice and support throughout my academic journey, for guiding and helping me find my way in this project. I also wish to thank Dr Jean Khalfa for his insights and sound advice, as well as Prof. -

Imaging Military Recruitment and the French Revolution Valerie Mainz

Days of Glory? Imaging Military Recruitment and the French Revolution Valerie Mainz War, Culture and Society, 1750 –1850 War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850 Series Editors Rafe Blaufarb Department of History Florida State University Tallahassee , Florida , USA Alan Forrest University of York , York , United Kingdom Karen Hagemann Netherlands Institute Advanced Study Wassenaar , Zuid-Holland , The Netherlands The century from 1750 to 1850 was a period of seminal change in world history, when the political landscape was transformed by a series of rev- olutions fought in the name of liberty. These ideas spread far beyond Europe and the United States: they were carried to the furthest outposts of empire, to Egypt, India and the Caribbean, and they would continue to inspire anti-colonial and liberation movements in Central and Latin America throughout the fi rst half of the nineteenth century. The Age of Revolutions was a world movement which cries out to be studied in its global dimension. But it was not only social and political institutions that were transformed by revolution in this period. So, too, was warfare. During the quarter-century of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars in particular, Europe was faced with the prospect of 'total' warfare with mass mobilization on a scale that was unequalled until the Great Wars of the twentieth century. Those who lived through the period shared for- mative experiences that would do much to shape their ambitions and forge their identities. The volumes published in this series seek to address -

Evaluation of Sustainability of Sewerage Systems in Metropolitan Areas

Evaluation of sustainability of sewerage systems in metropolitan areas. The case of Greater Paris Bernard Barraqué, Sophie Cambon To cite this version: Bernard Barraqué, Sophie Cambon. Evaluation of sustainability of sewerage systems in metropolitan areas. The case of Greater Paris: Economic analysis of the Milan wastewater treatment system : sustainability issues. 2006. halshs-00559225 HAL Id: halshs-00559225 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00559225 Submitted on 27 Jan 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Città di Milano Università Bocconi, IEFE Economic analysis of the Milan wastewater treatment system : sustainability issues Evaluation of sustainability of sewerage systems in other metropolitan areas The case of greater Paris B. Barraqué, DR CNRS, LATTS (ENPC – UMLV) S. Cambon-Grau, PhD, Ecole des Ponts 2 Table of contents Glossary of terms ...................................................................................................................................................3 General situation : approaches -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.