Grace Phelan Final/Diss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUN 1 9 1984 Archive$

CENTERS AND CENTRALITY: REFLECTIONS ON FRENCH CITY DESIGN by OLIVIER LESER Architecte Diplome Par"Le Gouvernement Ecole Nationale Superieure Des Beaux-Arts (UPI) June 1982 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1984 c OlivierLeser 1984 The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. A Signature of autho r Olivier Leser, Defartment of Architecture May 11, 1984 I Certified by lian Beina jProf. of Architecture, Thesis Supervisor Accepted by N. John Habraken, Chairman Departmental Committee for Graduate Studies MAt'SSACHUSETTS iNSTiTUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 1 9 1984 Archive$ LIBRARIES Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MILibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services hftp://Iibrardes.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Some pages in the original document contain text that runs off the edge of the page. CENTERS AND CENTRALITY: REFLECTIONS ON FRENCH CITY DESIGN by OLIVIER LESER SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MAY 1984 ABSTRACT This research looks at the tradition of centralizm in France and its implications on city design. -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA LEGAL NOTICES WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS A

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA December Vol. 630 Pretoria, 1 2017 Desember No. 41282 PART 1 OF 2 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 41282 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 41282 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 1 DECEMBER 2017 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Table of Contents LEGAL NOTICES BUSINESS NOTICES • BESIGHEIDSKENNISGEWINGS Gauteng ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Eastern Cape / Oos-Kaap ................................................................................................................. 13 Free State / Vrystaat ........................................................................................................................ 13 Western Cape / Wes-Kaap ................................................................................................................ 13 COMPANY NOTICES • MAATSKAPPYKENNISGEWINGS Gauteng ....................................................................................................................................... 14 LIQUIDATOR’S -

Fair Shares for All

FAIR SHARES FOR ALL JACOBIN EGALITARIANISM IN PRACT ICE JEAN-PIERRE GROSS This study explores the egalitarian policies pursued in the provinces during the radical phase of the French Revolution, but moves away from the habit of looking at such issues in terms of the Terror alone. It challenges revisionist readings of Jacobinism that dwell on its totalitarian potential or portray it as dangerously Utopian. The mainstream Jacobin agenda held out the promise of 'fair shares' and equal opportunities for all in a private-ownership market economy. It sought to achieve social justice without jeopardising human rights and tended thus to complement, rather than undermine, the liberal, individualist programme of the Revolution. The book stresses the relevance of the 'Enlightenment legacy', the close affinities between Girondins and Montagnards, the key role played by many lesser-known figures and the moral ascendancy of Robespierre. It reassesses the basic social and economic issues at stake in the Revolution, which cannot be adequately understood solely in terms of political discourse. Past and Present Publications Fair shares for all Past and Present Publications General Editor: JOANNA INNES, Somerville College, Oxford Past and Present Publications comprise books similar in character to the articles in the journal Past and Present. Whether the volumes in the series are collections of essays - some previously published, others new studies - or mono- graphs, they encompass a wide variety of scholarly and original works primarily concerned with social, economic and cultural changes, and their causes and consequences. They will appeal to both specialists and non-specialists and will endeavour to communicate the results of historical and allied research in readable and lively form. -

Aesthetics in Ruins: Parisian Writing, Photography and Art, 1851-1892

Aesthetics in Ruins: Parisian Writing, Photography and Art, 1851-1892 Ioana Alexandra Tranca Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Trinity College March 2017 I would like to dedicate this thesis to my parents, Mihaela and Alexandru Declaration I hereby declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. This dissertation does not exceed the prescribed word limit of 80000, excluding bibliography. Alexandra Tranca March 2017 Acknowledgements My heartfelt gratitude goes to my Supervisor, Dr Nicholas White, for his continued advice and support throughout my academic journey, for guiding and helping me find my way in this project. I also wish to thank Dr Jean Khalfa for his insights and sound advice, as well as Prof. Alison Finch, Prof. Robert Lethbridge, Dr Jann Matlock, and Prof. -

Adirondack Recreational Trail Advocates (ARTA)

Adirondack Recreational Trail Advocates (ARTA) Proposal for the Adirondack Rail Trail Photo: Lake Colby Causeway, Lee Keet, 2013 Submitted by the Board of Directors of ARTA Tupper Lake: Hope Frenette, Chris Keniston; Maureen Peroza Saranac Lake: Dick Beamish, Lee Keet, Joe Mercurio; Lake Clear: David Banks; Keene: Tony Goodwin; Lake Placid: Jim McCulley; Beaver River: Scott Thompson New York State Snowmobile Association: Jim Rolf WWW.TheARTA.org Adirondack Recreational Trail Advocates P.O. Box 1081 Saranac Lake, N.Y. 12983 Page 2 This presentation has been prepared by Adirondack Recreational Trail Advocates (ARTA), a not-for- profit 501(c)(3) corporation formed in 2011 and dedicated to creating a recreational trail on the largely abandoned and woefully underutilized rail corridor . © 2013, Adirondack Recreational Trail Advocates, Inc. Page 3 Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Original UMP Criteria Favor the Rail Trail .................................................................................................. 7 Changing the Status of the Corridor ........................................................................................................... 10 Classification as a Travel Corridor ......................................................................................................... 10 Historic Status ........................................................................................................................................ -

Aloysius Huber and May 15, 1848 New Insights Into an Old Mystery

LOWELL L. BLAISDELL ALOYSIUS HUBER AND MAY 15, 1848 NEW INSIGHTS INTO AN OLD MYSTERY I One of the memorable days in the French revolution of 1848 occurred on May 15. Several extraordinary events happened on that date. The first was the overrunning of the legislative chamber by an unruly crowd. Next, and most important, a person named Aloysius Huber, after several hours had elapsed, unilaterally declared the National Assembly dissolved. In the resultant confusion, the legislators and the crowd dispersed. Third, shortly afterwards, an attempt took place at the City Hall to set up a new revo- lutionary government. It failed completely. As the result of these happen- ings, a number of people thought to be, or actually, implicated in them were imprisoned on charges of sedition. Damaging consequences followed. Even before that day, a conservative pattern had started to emerge, as revealed by the late-April national election returns and the squelching of working-class unrest at Limoges and Rouen. Paris' day of turmoil sharply escalated the trend. Even though no lives were lost, the dissolution of the legislature and the attempt, no matter how feeble, to launch a new regime, amounted to a violation of the national sovereignty. This greatly offended many in the legislature and among the general public. The anti-working-class current that had started to emerge, but which it might have been possible to absorb, quickly expanded into an ultra-conservative torrent. Very soon after May 15 the authorities began the systematic harassment of the clubs. Only a month later the National Workshops were shut down. -

Surname First Name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen

2018 DRIVERS' CATEGORISATION LIST Updated on 09/07/2018 Drivers in red : revised categorisation Drivers in blue : new categorisation Surname First name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen Klaus Bronze Abbott Hunter Silver Abbott James Silver Abe Kenji Bronze Abelli Julien Silver Abergel Gabriele Bronze Abkhazava Shota Bronze Abra Richard Silver Abreu Attila Gold Abril Vincent Gold Abt Christian Silver Abt Daniel Gold Accary Thomas Silver Acosta Hinojosa Julio Sebastian Silver Adam Jonathan Platinum Adams Rudi Bronze Adorf Dirk Silver Aeberhard Juerg Silver Afanasiev Sergei Silver Agostini Riccardo Gold Aguas Rui Gold Ahlin-Kottulinsky Mikaela Silver Ahrabian Darius Bronze Ajlani Karim Bronze Akata Emin Bronze Aksenov Stanislas Silver Al Faisal Abdulaziz Silver Al Harthy Ahmad Silver Al Masaood Humaid Bronze Al Qubaisi Khaled Bronze Al-Azhari Karim Bronze Alberico Neil Silver Albers Christijan Platinum Albert Michael Silver Albuquerque Filipe Platinum Alder Brian Silver Aleshin Mikhail Platinum Alesi Giuliano Silver Alessi Diego Silver Alexander Iradj Silver Alfaisal Saud Bronze Alguersuari Jaime Platinum Allegretta Vincent Silver Alleman Cyndie Silver Allemann Daniel Bronze Allen James Silver Allgàuer Egon Bronze Allison Austin Bronze Allmendinger AJ Gold Allos Manhal Bronze Almehairi Saeed Silver Almond Michael Silver Almudhaf Khaled Bronze Alon Robert Silver Alonso Fernando Platinum Altenburg Jeff Bronze Altevogt Peter Bronze Al-Thani Abdulrahman Silver Altoè Giacomo Silver Aluko Kolawole Bronze Alvarez Juan Cruz Silver Alzen -

Chapter 6: Bonaparte, the Press, and "Passive" Propaganda the Nature

The Genesis of Napoleonic Propaganda: Chapter 5 4/25/03 10:57 AM Chapter 6: Bonaparte, the Press, and "Passive" Propaganda The Nature of "Passive" Propaganda 1 That Napoleon Bonaparte actively fostered the creation of his public image can hardly be doubted. From the manipulation of the French press through his carefully crafted dispatches, to the founding of newspapers that promoted his public image, to the innovative use of medals and medallions, he thoroughly mastered virtually every public medium of his day. Although other figures in history had manipulated these various media-Louis XIV, for example, employed painters, medal-makers, and journalists to promote his regal glory 1-Bonaparte was the first private citizen in modern history to realize the limitless possibilities open to a master propagandist. One question remains: How can we judge the effectiveness of his image-making campaign? Most historians agree that this self-promotion was a resounding success, but there is no direct method by which to measure its impact on the French populace. One way to attempt to evaluate the impact of Napoleon's efforts, however, is through what I will call "passive" propaganda, or secondary sources of media exposure initiated by others who sought to "cash in" on Napoleon's growing popularity. In the realm of "passive propaganda," Bonaparte's own efforts created a public demand for news about his achievements, which the French press, street-hawkers, engravers, and artists hurried to satisfy. This passive propaganda, unsought but not unwelcome, complemented and amplified Bonaparte's earlier image-making efforts. During the first few months of Bonaparte's command in Italy, the French press paid scant attention to the Italian campaign. -

Actas Colóquio – Literatura E História

João Medina Estética e Terror: o romance “Os deuses têm sede” de Anatole France “Que a guilhotina salve a pátria (...). Santa guilhotina, salva a pátria!” Fala de Gamelin em Os Deuses têm Sede, de Anatole France. “(...) quem se recusar a obedecer à vontade geral será obrigado a fazê-lo por todo o corpo; o que não significa outra cosia senão que será forçado a ser livre.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Do Contrato Social, livr. I. cap.VII. O romance histórico de Anatole France Os Deuses têm Sede, publicado em 1912, situado no período do Terror (1793 em diante, até aos começos do Directório), pertence ao período de desilusões do seu autor, já depois de o affaire Dreyfus ter tido o seu desfecho favorável ao capitão alsaciano, entretanto oficialmente reabilitado e reintegrado no exército. O seu autor tinha já 68 anos (nascera em 1844). Em 1908 publicara uma história paródica da França em tons ácidos e nada complacentes para com os seus compatriotas, sobretudo os contemporâneos, intitulada A Ilha dos Pinguins. Nesse mesmo ano saíra uma Joana de Arc escrita em veia semelhante de sarcasmo e desencanto. Com o romance histórico de 1912 adensava-se a sua visão pessimista e impiedosa, atendendo em especial aos seus pressupostos político-ideológicos de republicano socializante e dreyfusista empenhado no affaire, ao qual dedicara, aliás, alguns anos antes, uma tetralogia sob o título geral de História contemporânea: os romances O Olmo do Mail, O Manequim de Vime (1897), O Anel de Ametista (1898) e O Sr. Bergeret em Paris (1901), de que se fez na época tradução portuguesa111. -

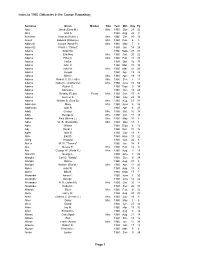

Index to 1960 Obituaries in the Canton Repository Page 1

Index to 1960 Obituaries in the Canton Repository Surname Given Maiden Title Year Mth Day Pg Abel Jacob (Clara M.) Mrs. 1960 Dec 28 32 Abel John A. 1960 Aug. 29 9 Ackelson Thomas (Ruth I.) Mrs. 1960 Dec 10 10 Ackert Edward (Patience) Mrs. 1960 Feb. 6 8 Adamcik Joseph (Anna P.) Mrs. 1960 May 7 6 Adametz Frank J. "Chant" 1960 Jan. 14 29 Adams Bright M. 1960 Sept. 28 28 Adams Ella May Mrs. 1960 Oct. 20 22 Adams Ethel A. Mrs. 1960 Feb. 15 20 Adams Helen 1960 Oct. 16 37 Adams John H. 1960 Mar. 31 39 Adams John W. Mrs. 1960 Mar. 21 26 Adams Joseph 1960 Apr. 13 24 Adams Minnie Mrs. 1960 Apr. 19 15 Adams Robert C. (Celestie) Mrs. 1960 Dec 3 11 Adams Robert L. (Catherine) Mrs. 1960 June 15 56 Adams Robert S. 1960 Sept. 9 14 Adams Samuel L. 1960 Jan. 19 20 Adams Schalto (Retta) Peary Mrs. 1960 Oct. 15 8 Adams Sumner S. 1960 July 28 10 Adams William B. (Zula B.) Mrs. 1960 Aug. 23 34 Adamson Mary Mrs. 1960 June 5 36 Addleman John R. 1960 Apr. 6 23 Addy George Mrs. 1960 Oct. 16 38 Addy George D. Mrs. 1960 Oct. 17 18 Adkins Paul (Wilma L.) Mrs. 1960 May 10 8 Adler WR(DllMW. R. (Della May ) Mrs. 1960 May 17 8 Adler William 1960 Sept. 6 16 Ady Oscar J. 1960 Dec. 31 12 Agler John B. 1960 July 19 8 Ahle Earl D. 1960 Nov. 18 22 Ailing Howard 1960 Oct. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRaPHY ARCHIVaL (UNPRINTED) SOuRCEs Archivio di Stato, Bologna, Archivio del Torrone: Fondo Processi, no. 5246, fols. 101r.–104v. Archivio di Stato, Venice, S. Uffizio, b. 72, ‘Costantino Saccardino’. Archivio di Stato, Rome, Fondo Università, b. 67, fol. 113v. Archivio di Stato, Bologna, Legato: Expeditiones, b. 172, fol. 155v. Archivio per la Congregazione della Dottrina della Santa Fede (ACDF), Siena. Acta Sanctae Sedis, Studio, 60, licence of 17 August 1640. British Library, Sloane ms 38, fol. 24v. Finnish Literature Society Archives, Manuscript card files, Perinnelajikortistot: Legendat. Koninklijke Bibliothek, The Hague, Ms. 76 F 5, fol. 43r. Koninklijke Bibliothek, The Hague, Ms. 78 D 38, vol. 1, fol. 175v. National Archives of Denmark, Viborg, Appellate court in Viborg 1617. National Archives of Finland (NA), Rural District Court Records: Ala-Satakunta I. ‘Tuokko’ register of rural court records http://digi.narc.fi/digi/dosearch.ka?new =1&haku=tuomiokirjakortisto. SOuRCEs aND BIbLIOGRaPHY PRINTED BEFORE 1900 Acerbi, Joseph (1802) Travels through Sweden, Finland, and Lapland to the North Cape In the Years 1798 and 1799, vol. II (London). Acta sanctorum (1643) Jan., vol. 1 (Antwerp: Ioannes Meursius). © The Author(s) 2017 301 L.N. Kallestrup, R.M. Toivo (eds.), Contesting Orthodoxy in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32385-5 302 BibliOGraphY Acta sanctorum (1668) Mar., vol. 3 (On Marie de Maillé) (Antwerp: Jacobus Meursius). Acta sanctorum (1668) Mar., vol. 2 (Antwerp: Jacobus Meursius). Acta sanctorum (1695) Jun., vol. 1 (Antwerp: Henricus Thieullier). Acta sanctorum (1735) Aug., vol. 2 ‘Acta B. Joannis Firmani sive Alvernicolae,’ c. -

Proceedings of the 8Th Annual Python in Science Conference

Proceedings of the 8th Python in Science Conference SciPy Conference – Pasadena, CA, August 18-23, 2009. Editors: Gaël Varoquaux, Stéfan van der Walt, K. Jarrod Millman Contents Editorial 2 G. Varoquaux, S. van der Walt, J. Millman Cython tutorial 4 S. Behnel, R. Bradshaw, D. Seljebotn Fast numerical computations with Cython 15 D. Seljebotn High-Performance Code Generation Using CorePy 23 A. Friedley, C. Mueller, A. Lumsdaine Convert-XY: type-safe interchange of C++ and Python containers for NumPy extensions 29 D. Eads, E. Rosten Parallel Kernels: An Architecture for Distributed Parallel Computing 36 P. Kienzle, N. Patel, M. McKerns PaPy: Parallel and distributed data-processing pipelines in Python 41 M. Cieślik, C. Mura PMI - Parallel Method Invocation 48 O. Lenz Sherpa: 1D/2D modeling and fitting in Python 51 B. Refsdal, S. Doe, D. Nguyen, A. Siemiginowska, N. Bonaventura, D. Burke, I. Evans, J. Evans, A. Fruscione, E. Galle, J. Houck, M. Karovska, N. Lee, M. Nowak The FEMhub Project and Classroom Teaching of Numerical Methods 58 P. Solin, O. Certik, S. Regmi Exploring the future of bioinformatics data sharing and mining with Pygr and Worldbase 62 C. Lee, A. Alekseyenko, C. Brown Nitime: time-series analysis for neuroimaging data 68 A. Rokem, M. Trumpis, F. Pérez Multiprocess System for Virtual Instruments in Python 76 B. D’Urso Neutron-scattering data acquisition and experiment automation with Python 81 P. Zolnierczuk, R. Riedel Progress Report: NumPy and SciPy Documentation in 2009 84 J. Harrington, D. Goldsmith The content of the articles of the Proceedings of the Python in Science Conference is copyrighted and owned by their original authors.