The Practical Shop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Routers for Router Tables New-Breed Models Spare You the Expense of a Router Lift

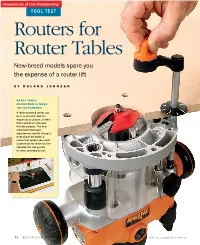

Compliments of Fine Woodworking TOOL TEST Routers for Router Tables New-breed models spare you the expense of a router lift BY ROLAND JOHNSON ABOVE-TABLE ADJUSTMENTS MAKE THE DIFFERENCE A table-mounted router can be very versatile. But it’s important to choose a router that’s designed expressly for that purpose. The best allow both bit-height adjustments and bit changes from above the table. A router that makes you reach underneath for these routine adjustments will quickly become annoying to use. 54 FINE WOODWO R K in G Photo, this page (right): Michael Pekovich outers are among the most versatile tools in the shop—the go-to gear Height adjustment Rwhen you want molded edges on lumber, dadoes in sheet stock, mortises for Crank it up. All the tools for adjusting loose tenons, or multiple curved pieces bit height worked well. Graduated that match a template. dials on the Porter-Cable Routers are no longer just handheld and the Triton are not tools. More and more woodworkers keep very useful. one mounted in a table. That gives more precise control over a variety of work, us- ing bits that otherwise would be too big to use safely. A table allows the use of feather- boards, hold-downs, a miter gauge, and other aids that won’t work with a hand- held router. With a table-mounted router, you can create moldings on large or small stock, make raised panels using large bits, cut sliding dovetails, and much more. Until recently, the best way to marry router and table was with a router lift, an expensive device that holds the router and allows you to change bits and adjust cut- ting height from above the table. -

Power Tool Guide 05J50.01

Power Tool Guide 05J50.01 The Veritas® Power Tool Guide is a collapsible straightedge that can be clamped to any material under 1" thick. The 52" tool guide (05J50.03) can be clamped across sheet material up to 52". The 8' Power Tool Guide (05J50.01), or the 48" tool guide extension (05J50.04) added to the 52" tool guide, can be clamped across sheet material up to 100". The advantage this guide has over other 8' guides is that it may be dismantled quickly and easily for cutting smaller sheet material as well as for easier storage or transport. The guide includes a pair of 1" capacity clamps that can be positioned anywhere along its length. For clamping material thicker than plywood sheets, a pair of 2" capacity clamps (05J50.09) is available separately. An optional 12" traveller (05J50.02) used in conjunction with a user-made base plate ensures that your power tool will effortlessly follow the intended line with greater safety. The utility of the traveller is further enhanced with the optional position stop (05J50.10) that clamps onto either guide rail. Figure 1: Veritas® Power Tool Guide. Safety Rules These safety instructions are meant to complement those that came with your power tool. We suggest that you reread those, in addition to these listed here before you begin to use this product. To use this product safely, always follow both sets of safety and general instructions. 1. Read the manual. Learn the tool’s applications and limitations as well as the specific hazards related to the tool. -

All-Star Router Jigs

All-Star 8Router Jigs Make your tool a multi-tasker with this problem-solving arsenal. By Joe Hurst-Wajszczuk W Cutting circles, arcs, and ovals hen I bought my first you can employ selected jigs router twenty years ago, visions to rout panels too unwieldy to of roundovers, chamfers, and safely machine on a router table. After hanging the final sheet ogees filled my head. Believing Over the next few pages, we’ll of drywall in my last shop, my the router should be saved for help you build an arsenal of drywall square found a higher edge treatments, it sat idle on hardworking router jigs, some the shelf as I struggled to build of which are fresh spins on projects with a collection of rough old, reliable classics. I tweaked carpentry tools and a rebuilt the designs and used quality radial-arm saw. Now several years materials to make a sweet and four routers later, I view the collection of precision achievers tool as a multi-tasking Swiss-army that suit several needs while knife, ready to partner with any providing years of service. With numbers of jigs and accessories. just a small investment in time Additionally, jig-mounted and materials the resulting jigs routers provide great small-shop Note:won’t Somejust look of the good, jig dimensionsthey’ll ramp Mark lines on the acrylic to solutions. You can capitalize mayup your require craftsmanship adjustments too. to indicate the bit’s location. Nip on their versatility in limited- fit your machine. See “Making the corners off the bottom space shops, performing tasks the Jigs to Fit,” page 31. -

BRAD POINT DOWEL DRILL Solid Carbide • 57.5Mm & 70Mm Long • 10Mm X 30Mm Shank* Special Solid Carbide Grade Cutting Flute for Long Lasting Performance

BRAD POINT BORING Carbide Tipped • 57mm Long • 10mm x 30mm Shank* Tool No. Tool No. ØD B Ød L LH RH 3mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301003 201003 † 3.2mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301032 201032 4mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301004 201004 4.5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm — 201045 Brad Point Boring Bits are coated with a non-stick 5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301005 201005 coating for longer lasting cutting edge and tool life. This special Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) non-stick color coating is 5.1mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301051 201051 applied onto the bit at a temperature of 570° F. The coating reduces the 5.2mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301052 201052 friction between the chip and the body inside the flute and it helps to clear 5.5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301055 201055 the chips out of the hole during the drilling, creating a cooler drilling area 6mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301006 201006 with no burning and a longer lasting cutting edge. 6.5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301065 201065 6.7mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301067 201067 In cases where the carbide tip cutting edges are coated, there is no need to sand the coating off before use. Once the tool starts drilling, the coating 7mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301070 201070 is quickly cleared off the needed cutting edge. 7.5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301075 201075 8mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301008 201008 d d 8.2mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301082 201082 9mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301090 201090 10mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301010 201010 10.5mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301105 201105 12mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301012 201012 14mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301014 201014 L L 15mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301015 201015 16mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301016 — B B 17mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301017 201017 18mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301018 201018 19mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301019 201019 D D 20mm 27mm 10mm 57mm 301020 201020 Left Hand Right Hand 3/16 27mm 10mm 57mm 301047 — 1/4 27mm 10mm 57mm 301007 201007 3/8 27mm 10mm 57mm 301009 201009 1/2 27mm 10mm 57mm 301013 201013 † With solid carbide cutting edge. -

Router Table

Router Table Read This Important Safety Notice To prevent accidents, keep safety in mind while you work. Use the safety guards installed on power equipment; they are for your protection. When working on power equipment, keep fingers away from saw blades, wear safety goggles to prevent injuries from flying wood chips and sawdust, wear hearing protection and consider installing a dust vacuum to reduce the amount of air- borne sawdust in your woodshop. Don’t wear loose clothing, such as neckties or shirts with loose sleeves, or jewelry, such as rings, necklaces or bracelets, when working on power equipment. Tie back long hair to prevent it from getting caught in your equipment. People who are sensitive to certain chemicals should check the chemical con- tent of any product before using it. Due to the variability of local conditions, construction materials, skill levels, etc., neither the author nor Popular Woodworking Books assumes any responsibility for any accidents, injuries, damages or other losses incurred resulting from the mate- rial presented in this book. The authors and editors who compiled this book have tried to make the con- tents as accurate and correct as possible. Plans, illustrations, photographs and text have been carefully checked. All instructions, plans and projects should be carefully read, studied and understood before beginning construction. Prices listed for supplies and equipment were current at the time of publica- tion and are subject to change. Metric Conversion Chart to convert to multiply by Inches. Centimeters. 2.54 Centimeters. Inches . 0.4 Feet. Centimeters. 30.5 Centimeters. Feet. 0.03 Yards. -

Router Tools Designed for Machining Mechanical Plastics Provide an Opportunity to Maximize Productivity. Way

MAY 2005 / VOLUME 57 / NUMBER 5 BY VAN NISER, ONSRUD CUTTER LP The Router tools designed for machining mechanical plastics provide an opportunity to maximize productivity. Way tics include acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), Acetal, Delrin, Hydex, nylon, polycarbonate, polyurethane and polyethylene terephtalate (PET). Cutting Tool Geometry Router bits for cutting mechanical plastics have traditionally been run on CNC routers at high spindle speeds and feed rates. Extensive testing and years of field experience have shown that a tool with a high rake and low clearance performs exceptionally well. It ma- chines mechanical plastics more pro- ductively than tools with other geome- tries and imparts a finer surface finish (Figure 1). This kind of free-cutting geometry is rarely used by shops to machine me- chanical plastics. Most use endmills run- ning on CNC milling machines. Endmills are robust cutting tools specifically designed for heavy loads, All images: Onsrud Cutter slower spindle speeds and lower feed any wear parts are made from Traditionally, these types of parts rates. These tools, with their minimal mechanical plastics. Common have been fabricated from metal. But flute area, interfere with the ability to M ones include bearings, gears, mechanical plastics are beginning to re- clear the stringy chips generated when material-handling parts and machine place metal because of their increased machining mechanical plastics. Endmills components such as spacers and posi- durability, excellent machinability, and are designed with minimal rake and low tioning mounts where the reduction of exceptional mechanical and electrical clearance, which can aggravate the melt- vibration is essential. properties. Common mechanical plas- ing and rewelding problems common when cutting mechanical Chip Load plastics. -

ROUTER-TABLE BASICS Want More from Your Router? Turn It on Its Head

ROUTER-TABLE BASICS Want more from your router? Turn it on its head. By Joe Hurst-Wajszczuk n terms of woodworking mach- small shaper. This arrangement This primer will help you begin inery, hand-held routers earn leaves your hands free to manipu- to unlock the powerful potential Ithe workshop MVP award. late the work, and enables you to of your most prized tool in the Considering how easy they are use stops, fences, and hold-downs shop. To start, follow the set-up to use freehand or paired with a to control the cut. This orientation sequence below, and then review jig, it’s not surprising to discover also offers a fresh vantage, allowing the advice about proper feed and that many woodworkers haven’t you to see what the bit is doing to guidance. Next, check out the considered pointing the bit up. the work. techniques for profiling edges and Mounting a router in a table Using a table-mounted router joinery. You’ll soon wonder how tranforms this handy tool into a isn’t difficult, but it isn’t fool-proof. you managed without it. Step 1: Level the insert Step 2: Set the bit height (3 ways) Step 3: Set the fence Standing square. A combination square is convenient because it can stand on its own next to the bit as you adjust the depth of cut. Although some rules are graduated in 64ths, those fine lines are tough on old eyes. Plan on making a few test cuts. Try building blocks. Key blocks enable you to set a bit’s height by sight and feel. -

Stanley Black and Decker Techtronic Industries Co Ltd (TTI) Chevron

Who Owns What? Andrew Davis May, 2019 This is a redacted version of an article II found on protoolreviews.com. I remember growing up when General Motors offered different brands at different price points (until they all the brands started to overlap before GM collapsed) – Cadillac at the top end, followed by Oldsmobile, Buick, Pontiac, and Chevy. We have a similar situation in woodworking tools (also in kitchen appliances) except that in the case of tools, the multi-brand company is more often a case of acquisitions rather than organic development. Anyway, for those readers interested in the business side of tools, this column, which is a departure from my usual thread, may be of interest. Stanley Black and Decker Stanley Black & Decker (SBD) turned heads when it bought Craftsman Tools in 2017 after Sears closed 235 stores in 2015. Dating back to 1843 with a man named Frederick Stanley, the company merged in 2010 with Black and Decker. As of 2017, the company maintains a $7.5 billion business in tools & storage alone. SBD brands include: DeWalt Stanley Black + Decker Bostitch Craftsman Vidmar Mac Tools Irwin Lenox Proto Porter-Cable Powers Fasteners Lista Sidchrome Emglo USAG Techtronic Industries Co Ltd (TTI) TTI owns Milwaukee Tool and a host of other power tool companies. It also licenses the RIDGID and RYOBI names for cordless power tools (Emerson actually owns RIDGID and makes the red tools). Founded in 1985 in Hong Kong, TTI sells tools all over the world and employs over 22,000 people. TTI had worldwide annual sales of over US$6 billion in 2017. -

CNC Plasma Cutters, CNC Router Tables, CNC Water Jet Tables

CNCCNC PlasmaPlasma Cutters,Cutters, CNCCNC RouterRouter Tables,Tables, CNCCNC WaterWater JetJet Tables,Tables, CNCCNC PipePipe CuttersCutters One Stop For All Your CNC Industrial Cutter Tables Made In The USA! 2 Year Warranty Lifetime telephone technical support Spitfire Features: Linear precision guide rails Automatic Torch Height Control – Magnetic Breakaway Clamp Stepper Motors 4” Deep Water Bed – Slats Included (optional 8” water bed available) Ball Screw Lifter Rack and Pinion (X,Y) User Friendly Operator Interface PC Controller (Monitor/Tower/Keyboard/mouse) – Windows Operating System Sizes: 2x2, 2x4, 4x4, 4x8, 4x10, 4x12, 5x5, 5x10 Machine Specifications: Software Specifications: ➔ Positioning Accuracy: (+/-) .007 ➔ 2D Design & Layout Tools, layer control, ➔ Repeatability: (+/-) .002 lines, snap grid ➔ Overall Machine Height: 45 inches ➔ True Shape Nesting ➔ Max. Traverse Speed: 800ipm ➔ Test Editing File Import: DWG, DXF, EPS, ➔ Max. Tools 2: 1 Plasma 1 Scribe AI, PDF ➔ Input Power-Machine Drive: 110V 50/60Hz ➔ Image File Import: BMP, JPEG, TIP, GIF 1-Phase ➔ Pierce Delay Time ➔ Max. Plasma System Amperage: 125amps ➔ Optional Ramp Piercing to Reduce Blowback ➔ Visual G-Code Display ➔ Real time Cut Display ➔ Torch On/Off from Screen 2 Year Warranty ➔ THC On/Off from Screen Lifetime telephone technical support Trooper Features: Automatic Ball Screw Torch Height Control Dual Rack and Pinion Servo Motor Drive (X, Y) Heavy Duty Trucks HIWIN Linear Precision Guide Rails Fully Welded Frame Limit and Homing Switches Heavy Steel Construction E-Chain Cable Track 3”x3” Extruded Aluminum Bridge 12” Waterbed, Pneumatic Waterbed, Box Style Downdraft Table, or Zoned Downdraft Table Available Sizes: 4x4, 4x8, 5x5, 5x10, 6x10, 6x12, 6x18 Machine Specifications: Software Specifications: ➔ Positioning Accuracy: (+/-) .007 ➔ 2D Design & Layout Tools, layer control, ➔ Repeatability: (+/-) .002 lines, snap grid ➔ Max. -

Section V - Air & Power Tools

Section V - Air & Power Tools SECTION V - TABLE OF CONTENTS A Section V Contents: B Routers, → Routers.......................................................2-6 pages V-2 - V-6 C Sanders, Air............................................6-11 Sanders, Electric...................................11-14 D Drills & Air Hammers...........................15-17 Pinners, Staplers and Nailers..............18-20 EE Air Tool Oil and Blow Guns................21-23 FF Air Tool Fittings.....................................24-25 ↑Sanders, Air & Electric → Air Line Accessories.............................26-28 pages V-6 - V-14 G Air Hose and Fittings........................... 28-29 Dust Extractors..................................... 30-31 H Inspection Lighting.....................................32 Heat Guns................................................. 33 I Domino and Biscuit Joiners................. 34-35 Jigsaws................................................. 36-37 J Track Saws and Accessories...............38-39 KK Miter and Table Saws, Planers.................40 L MM Belt Sanders, → ↑ Staplers, Pinners & Nailers, page V-14 NN pages V-18 - V-20 OO PP Dust Extraction, → QQ page V-30 - V-31 R S Drills, ↑ T pages V-15 - V-17 U V WW XX Y Air Tools & Hose Fittings, Track Saws, page V-38 ↑ Joiners, pages V-34 - V-35 ↑ ↑ pages V-24 - V-29 800-289-2237 • WWW.WURTHBAERSUPPLY.COM • WÜRTH BAER SUPPLY V - 1 Section V - Air & Power Tools A ROUTERS B Colt™ Palm Router, 1 HP • Variable speed dial is conveniently mounted on top of the tool body C • Simple depth adjustment, just align and lower the motor and then lock the router in position with D the clamping level • Micro-fine adjustments via wheel on the back of the router’s base E • Accepts standard 1/4 In. bits with max cutter diameter of 1-5/16” • Includes: Fixed Base, 1/4 In. -

Unit Nine: Power Tools Drill, Router, Sander Lesson #1: Router Safety Packet

Unit Nine: Power Tools Drill, Router, Sander Lesson #1: Router Safety Packet Objectives Students will be able to… . Identify the router’s major components and safety operation. Common Core Standards LS 11-12.6 RSIT 11-12.2 RLST 11-12.2 Health and Safety 6.0, 6.2, 6.3, 6.5, 6.6 Technical Knowledge and Skills 10.0, 10.1, 10.2 Demonstration and Application 11.1 Cabinetmaking and Wood Products Pathway A4.1, 4.3, & A4.4 Residential and Commercial Construction Pathway D2.1, D3.1, D3.2, D3.3 Materials Router Identification and Safety Worksheet YouTube Video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZkerM8R8Pj8 Lesson Sequence . Complete the Router Identification and Safety Worksheet with students gathered around the Router. As the parts of the Router, not only discuss what their function is, but also demonstrate how they function. (20 minutes) . Return to the classroom and have students work on the safety questions. (15-20 minutes) . Watch the YouTube Video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZkerM8R8Pj8 answer any questions students may have. (8 minutes) © BITA: A program promoted by California Homebuilding Foundation BUILDING INDUSTRY TECHNOLOGY ACADEMY: YEAR ONE CURRICULUM Assessment Monitor student understanding of the router components and safety through questioning. Call on random students to answer questions. Provide feedback as needed. Accommodations/Modifications -one on one support -partner as needed -check for understanding © BITA: A program promoted by California Homebuilding Foundation BUILDING INDUSTRY TECHNOLOGY ACADEMY: YEAR ONE CURRICULUM Router Identification and Safety Part 1: Identify the numbered parts on the router illustrated below. 1.____________________________________ 7. -

Attaching the Leigh E-Bush to the Router

69 D4R Pro - Appendix I Attaching the Leigh e-Bush to the Router The correct guidebush is the vital link between the router and your Leigh Jig. It precisely steers the router. Where possible, always use the Leigh system to ensure correct bush length and precise diameter for accurate results. Leigh offers the adaptors below to fit guidebushes to over one hundred router models new and old, including Porter Cable, Black & Decker, and DeWalt. Many other makes like Bosch, Fein, Festool, Milwaukee etc., include or offer base adaptors. See a list of routers in the Guide Bushing and Adaptor Selection Chart on the next page. Leigh Guide Bushing and Adaptor System e7 711C e10 716C eBush Mounting Variations 721 RA1126 RA1129 Set of two Bosch Adaptors: RA1126 and RA1100 704R RA1100 eBush with eBushes fit many Adaptors 702 & 702R routers directly 702 705R 702R 706R 703 710 eBush with eBush with Adaptor 703 Adaptor 710 Nut for e-Bushes and C Guide Bushings 70 Appendix I D4R Pro User Guide ATTACHING THE LEIGH E-BUSH TO THE ROUTER Guide Bushing and Adaptor Selection Leigh dovetail jigs require a router fitted with a guide bushing. An adaptor may be required to fit the bushing to the router. Visit Leightools.com for a complete list of routers. 1 ROUTER 2 ROUTER 3 ROUTER 4 7/16" OD 5 5/8" OD DIRECTIONS MAKER MODEL ADAPTOR BUSHING ◆ BUSHING ▲ OFE 710 in plunge base Not Required e7 or 711C 716C A. Locate name of router maker in AEG OFSE 2000 703 e7 or 711C 716C Column 1.