GERRIT NOORDZIJ the Mannerist Writing-Book and Stanley Morison In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER 43 Antikvariat Morris · Badhusgatan 16 · 151 73 Södertälje · Sweden [email protected] |

NEWSLETTER 43 antikvariat morris · badhusgatan 16 · 151 73 södertälje · sweden [email protected] | http://www.antikvariatmorris.se/ [dwiggins & goudy] browning, robert: In a Balcony The Blue Sky Press, Chicago. 1902. 72 pages. 8vo. Cloth spine with paper label, title lettered gilt on front board, top edge trimmed others uncut. spine and boards worn. Some upper case letters on title page plus first initial hand coloured. Introduction by Laura Mc Adoo Triggs. Book designs by F. W. Goudy & W. A. Dwiggins. Printed in red & black by by A.G. Langworthy on Van Gelder paper in a limited edition. This is Nr. 166 of 400 copies. Initialazed by Langworthy. One of Dwiggins first book designs together with his teacher Goudy. “Will contributed endpapers and other decorations to In a Balcony , but the title page spread is pure Goudy.” Bruce Kennett p. 20 & 28–29. (Not in Agner, Ransom 19). SEK500 / €49 / £43 / $57 [dwiggins] wells, h. g.: The Time Machine. An invention Random House, New York. 1931. x, 86 pages. 8vo. Illustrated paper boards, black cloth spine stamped in gold. Corners with light wear, book plate inside front cover (Tage la Cour). Text printed in red and black. Set in Monotype Fournier and printed on Hamilton An - dorra paper. Stencil style colour illustrations. Typography, illustra - tions and binding by William Addison Dwiggins. (Agner 31.07, Bruce Kennett pp. 229–31). SEK500 / €49 / £43 / $57 [bodoni] guarini, giovan battista: Pastor Fido Impresso co’ Tipi Bodoniani, Crisopoli [Parma], 1793. (4, first 2 blank), (1)–345, (3 blank) pages. Tall 4to (31 x 22 cm). -

Sig Process Book

A Æ B C D E F G H I J IJ K L M N O Ø Œ P Þ Q R S T U V W X Ethan Cohen Type & Media 2018–19 SigY Z А Б В Г Ґ Д Е Ж З И К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ч Ц Ш Щ Џ Ь Ъ Ы Љ Њ Ѕ Є Э І Ј Ћ Ю Я Ђ Α Β Γ Δ SIG: A Revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Type & Media 2018–19 ЯREthan Cohen ‡ Submitted as part of Paul van der Laan’s Revival class for the Master of Arts in Type & Media course at Koninklijke Academie von Beeldende Kunsten (Royal Academy of Art, The Hague) INTRODUCTION “I feel such a closeness to William Project Overview Morris that I always have the feeling Sig is a revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Halbfette. My primary source that he cannot be an Englishman, material was the Klingspor Kalender für das Jahr 1933 (Klingspor Calen- dar for the Year 1933), a 17.5 × 9.6 cm book set in various cuts of Wallau. he must be a German.” The Klingspor Kalender was an annual promotional keepsake printed by the Klingspor Type Foundry in Offenbach am Main that featured different Klingspor typefaces every year. This edition has a daily cal- endar set in Magere Wallau (Wallau Light) and an 18-page collection RUDOLF KOCH of fables set in 9 pt Wallau Halbfette (Wallau Semibold) with woodcut illustrations by Willi Harwerth, who worked as a draftsman at the Klingspor Type Foundry. -

Berthold Wolpe Geboren Am 29

Berthold Wolpe Geboren am 29. Oktober 1905 in Offenbach am Main, gestorben am 5. Juli 1989 in London. Nach dem Abitur 1925 Lehre als Bronzegießer, in der Hauptsache aber als Ziseleur. 1925–1928 Technische Lehr- anstalten in Offenbach. Mitglied in der »Offenbacher Werkgemein- schaft« von Rudolf Koch. Von 1929–1933 Lehrtätigkeit an den Techni- schen Lehranstalten Offenbach und gleichzeitig Lehrer für Schrift an der Kunstschule Frankfurt (später Städelschule). 1935 Emigration nach London. Dort Graphiker, Buchgestalter und Lehrer für Schrift (zuletzt am Royal College of Art, London). 1983 Aufnahme in den Order of the British Empire. http://www.klingspor-museum.de Albertus 1938 Monotype Linotype Albertus Light 1940 Monotype Linotype ALBERTUS TITLING 1936 Monotype Bold Titling 1940 Monotype Decorata 1956 Fanfare Press 1952 Bauer. Gießerei LTB Italic 1973 London Transport unveröffentlicht 1937 Monotype 1936 Monotype G. Helzel Sachsenwald Gotisch halbfett 1938 Monotype Sachsenwald Gotisch fett Monotype Titling 1936 Fanfare Press Wolpe Fraktur 1933 D. Stempel AG unveröffentlicht Abbildung siehe Anhang http://www.klingspor-museum.de Berthold Wolpe Collection Bearbeitung der Schriften von Berthold Wolpe durch Toshi Omagari für Monotype Albertus Nova Thin 2017 Monotype Linotype Albertus Nova Light 2017 Monotype Linotype Albertus Nova 2017 Monotype Linotype Albertus Nova Bold 2017 Monotype Linotype Albertus Nova Black 2017 Monotype Linotype Sachsenwald Light 2017 Monotype Linotype Sachsenwald 2017 Monotype Linotype Wolpe Fanfare Thin 2017 Monotype -

„Bitstream“ Fonts

Key to the „Bitstream“ Fonts The history of typefaces is the history of forgeries. One of the greatest forgers of the 20th century was Matthew Carter. The Bitstream website (http://www.myfonts.com) describes him as follows: Matthew Carter of United Kingdom. Born: 1937 Son of Harry Carter, Royal Designer for Industry, contemporary British type designer and ultimate craftsman, trained as a punchcutter at Enschedé by Paul Rädisch, responsible for Crosfield's typographic program in the early 1960s, Mergenthaler Linotype's house designer 1965-1981. Carter co-founded Bitstream with Mike Parker in 1981. In 1991 he left Bitstream to form Carter & Cone with Cherie Cone. In 1997 he was awarded the TDC Medal, the award from the Type Directors Club presented to those „who have made significant contributions to the life, art, and craft of typography“. Carter’s „significant contribution to the life, art, and craft of typography“ consisted of forging the Linotype typeface collection. Carter can be characterized as a split personality. On the one hand, he has designed several original typefaces. On the other hand, he has forged hundreds of fonts. The following lists reveal that ca. 90% of the „Bitstream“ fonts are forgeries of the fonts contained in the catalog „LinoTypeCollection 1987“ („Mergenthaler Type Library“), i.e. the „Bitstream“ fonts are „nefarious evil knock-off clones“ (Bruno Steinert) of fonts sold by Linotype in the mid-1980s.1 „L“ in the following lists denotes that the font is contained in the „LinoTypeCollection 1987“. In the mid-1980s, the Linotype library comprised hundreds of typefaces with a total of 1700 fonts. -

Alphabet B Ooks Book Beautiful Cambridge Dodgson

a l phabet b ooks the b ook beautiful ambridge c odgson d from the library of christopher hogwood BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 40 SOUTH AUDLEY STREET, LONDON W1K 2PR +44 (0)20 7297 4888 [email protected] www.quaritch.com For enquiries about this catalogue, please contact: Anke Timmermann ([email protected]) or Mark James ([email protected]) Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC, 1 Churchill Place, London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-82 Swift code: BARCGB22 Sterling account IBAN: GB98 BARC 206582 10511722 Euro account IBAN: GB30 BARC 206582 45447011 US Dollar account IBAN: GB46 BARC 206582 63992444 Mastercard, Visa and American Express accepted. VAT number: GB 840 1358 54 Cheques should be made payable to: Bernard Quaritch Limited. List 2016/17 © Bernard Quaritch Ltd 2016 christopher hogwood cbe (1941- 0114 Throughout his 50-year career, conductor, musicologist and keyboard player Christopher Hogwood applied his synthesis of scholarship and performance with enormous artistic and popular success. Spearheading the movement that became known as ‘historically-informed performance’, he promoted it to the mainstream through his work on 17th- and 18th-century repertoire with the Academy of Ancient Music, and went on to apply its principles to music of all periods with the world’s leading symphony orchestras and opera houses. His editions of music were published by the major international houses, and in his writings, lectures and broadcasts he was admired equally for his intellectual rigour and his accessible presentation. Born in Notingham, Christopher was educated at Notingham High School, The Skinners' School, Royal Tunbridge Wells, and Pembroke College, University of Cambridge, where he read Classics and Music. -

Working with Koch Warren Chappell University of Virginia

The Kentucky Review Volume 2 | Number 2 Article 3 1981 Working with Koch Warren Chappell University of Virginia Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Art and Design Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Chappell, Warren (1981) "Working with Koch," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 2 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol2/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Working with Koch* Warren Chappell Fifty years ago, in the autumn of 1930, I began to make plans to learn to cut type punches. That fall my first book, Swift's A Tale of a Tub, was published by Columbia University Press. I did the typography, binding, and jacket, and engraved thirteen illustrations by my friend Charles Locke, instructor of lithography at the Art Students' League. The printing was the work of George Grady, who had been pressing me to learn punch cutting for at least three years. I had already earned a bachelor's degree from a university and had studied at the Art Students' League, where I was a member of the Board of Control. Also, I had been working as promotional art director for Liberty Magazine for two and a half years. -

Bitstream Font Name Aliases Fontotéka 3.0 Compiled by Petr Somol, Based on Jon A

Bitstream Font Name Aliases fontotéka 3.0 Compiled by Petr Somol, based on Jon A. Pastor‘s list from http://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~luc/jonpastor.txt. E-mail: [email protected] The list should not be considered complete, nor accurate. It is more a work in progress than anything else. Bitstream Name Common Name Designer(s) Date(s) Orig. Remarks/Attributions Vend. (all) (M.Macrone/J.Pastor,P.S.) (M.M,P.S.) (J.P., P.S.) Aachen Aachen Colin Brignall, Alan Meeks 1969-1977 17 Ad Lib Ad Lib Freeman Craw 1961 6 Aldine 401 Bembo Stanley Morison after Francesco 1929 after 1,4 Griffo / Giovanni Tagliente 1495 / 1520 Aldine 721 Plantin Frank Hinman Pierpont after ~1930 after 1,4 Robert Granjon‘s type used by 16th ~1550 / 16h century printer Christophe Plantin cent. Alternate Gothic No. 2 Alternate Gothic Morris Fuller Benton 1903 6 Amazone Amazone Leonard H. D. Smit 1958 12 Amelia Amelia Stanley Davis 1967 18, 2 American Text American Text Morris Fuller Benton 1932 6 Americana Americana Richard Isbell, Whedon Davis 1965 6 Aurora Aurora ? 1928 (c.) 11 Baker Signet Baker Signet Arthur Baker 1965 18 Balloon Balloon Max R. Kaufmann 1939 6 Bank Gothic Bank Gothic Morris Fuller Benton 1930-33 6 Baskerville Baskerville George W. Jones after John 1929 after 2 Baskerville ~1754-1775 Baskerville No.2 Baskerville No.2 ? ? 19 Bauer Bodoni Bauer Bodoni Heinrich Jost, Louis Höll after 1926 after 8 Giambattista Bodoni ~1800 Bell Gothic Bell Gothic Chauncey H. Griffith 1938 2 Belwe Belwe Georg Belwe before 1950 20 Bernhard Bold Con- Bernhard Bold Con- Lucian Bernhard -

A Tally of Types: with Additions by Several Hands Edited by Brooke Crutchley Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-09786-4 - Stanley Morison: A Tally of Types: With Additions by Several Hands Edited by Brooke Crutchley Frontmatter More information a tally of types © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-09786-4 - Stanley Morison: A Tally of Types: With Additions by Several Hands Edited by Brooke Crutchley Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-09786-4 - Stanley Morison: A Tally of Types: With Additions by Several Hands Edited by Brooke Crutchley Frontmatter More information stanley morison A with additions by several hands edited by brooke crutchley With a New Introduction by Mike Parker © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-09786-4 - Stanley Morison: A Tally of Types: With Additions by Several Hands Edited by Brooke Crutchley Frontmatter More information cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 8ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521097864 © Cambridge University Press 1973 Introduction © Mike Parker 1999 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. Mike Parker’s Introduction is published by arrangement with David R. -

The Field Guide to Typography

THE FIELD GUIDE TO TYPOGRAPHY TYPEFACES IN THE URBAN LANDSCAPE THE FIELD GUIDE TO TYPOGRAPHY TYPEFACES IN THE URBAN LANDSCAPE PETER DAWSON PRESTEL MUNICH · LONDON · NEW YORK To my parents, John and Evelyn Dawson Published in North America by Prestel, a member of Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH Prestel Publishing 900 Broadway, Suite 603 New York, NY 10003 Tel.: +1 212 995 2720 Fax: +1 212 995 2733 E-mail: [email protected] www.prestel.com © 2013 by Quid Publishing Book design and layout: Peter Dawson, Louise Evans www.gradedesign.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, or otherwise without written permission from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dawson, Peter, 1969– The field guide to typography : typefaces in the urban landscape / Peter Dawson. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-3-7913-4839-1 1. Lettering. 2. Type and type-founding. I. Title. NK3600.D19 2013 686.2’21—dc23 2013011573 Printed in China by Hung Hing CONTENTS_ Foreword: Stephen Coles 8 DESIGNER PROFILE: Rudy Vanderlans, Zuzana Licko 56 Introduction 10 Cochin 62 How to Use This Book 14 Courier 64 The Anatomy of Type 16 Didot 66 Glossary 17 Foundry Wilson 68 Classification Types 20 Friz Quadrata 70 Galliard 72 Garamond 74 THE FIELD GUIDE_ Goudy 76 Granjon 78 Guardian Egyptian 82 SERIF 22 ITC Lubalin Graph 84 Minion 86 Albertus 24 Mrs -

The Émigré Publishers and Book Artists in Britain

The Émigré Publishers and Book Artists in Britain eissenborn’s address book contained the names of some well known people: writers like Victor Bonham Carter as well asW luminaries from the printing world such as Stanley Morison of Monotype fame. There are also a number of German names among the contacts: Moritz Felsenstein, Erich Kahn, Erich Mendelssohn, Joseph Suschitzky, Georg Him among them. Others again may have been Anglo-Saxon names which were hiding the identity of German refugees: Peter Midgely was in fact Peter Fleischmann, a fellow in- ternee with Weissenborn on the Isle of Man. These German names belonged to people who formed the immigration that has been re- ferred to as ‘Hitler’s gift to Britain’. Weissenborn was one of the some 80,000 refugees who came to Britain between 1933 and the outbreak of the World War Two in September 1939.1 While Com- munists and Social Democrats were the first targets of Nazi action, as were for example trade unionists and others engaged in left-wing politics, the majority of the refugees (also known as ‘émigrés’ or ‘exiles’, sometimes with different implications) were either Jewish themselves, or, as in Weissenborn’s case, married to Jews. As Goeb- bels famously remarked, he decided who is a Jew, thereby enabling the Nazi authorities to remove from office people with one Jewish grandparent. Religious affiliation played no part in the programme, so that the fact that Weissenborn’s Jewish wife Edith Halberstam was non-practising was irrelevant to their policy of removing staff from institutes of higher education. -

20Th Century Type Designers

. IZMIR UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS FACULTY OF FINE ARTS AND DESIGN Alessandro Segalini, Dept. of Communication Design: alessandro.segalini @ ieu.edu.tr — homes.ieu.edu.tr/~asegalini TYPOGRAPHIC DESIGN 2oth century Type Designers Frederic W. Goudy (1865-1947) Frederic W. Goudy (1865-1947) Goudy was the oldest, one of the most prolific and dedicated of the great innovative type designers Bruce Rogers (1870-1957) of the last century, his remained fonts place him among the handful of designers who have changed the look of the types we read. Born in Bloomington, Illinois, at the age of 24 moved to Chicago and began a series of clerking jobs, then set up a freelance lettering artist for a number of stores, and later Rudolf Koch (1876-1934) got a teaching position at the Frank Holme School of illustration as a lettering tutor. He was him- self becoming increasingly fired by craft ideals. Commisioned by the America Lanston Monotype William Addison Dwiggins (1880-1956) designed the typeface called 38-E after his early designs Camelot, Pabst, Village, Copperplate Gothic, Kennerly and Forum titling. On 1945 ATF cut and produced the face designed on 1915 now known as Goudy Old Style. Goudy had a native American immunity to the austere European view on typogra- Eric Gill (1882-1940) phy; his types are individual, always recognisable. Stanley Morison (1889-1967) Bruce Rogers (1870-1957) Rogers was a book designer whose attention to the minutiæ of his work led him occasionally to the Giovanni Mardersteig (1892-1977) design of type, at the point that his major achievement in this field, Centaur, has been described by Prof. -

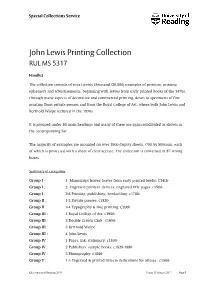

John Lewis Printing Collection RUL MS 5317

vls04fhb Section name Special Collections Service John Lewis Printing Collection RUL MS 5317 Handlist The collection consists of over twenty thousand (20,800) examples of printing, printing ephemera and advertisements, beginning with leaves from early printed books of the 1470s, through many aspects of decorative and commercial printing, down to specimens of fine printing from private presses and from the Royal College of Art, where both John Lewis and Berthold Wolpe lectured in the 1970s. It is grouped under 80 main headings and many of these are again subdivided as shown in the accompanying list. The majority of examples are mounted on over 1900 display sheets, (700 by 500mm), each of which is protected with a sheet of clear acetate. The collection is contained in 87 strong boxes. Summary of categories Group I : 1 Manuscript leaves; leaves from early printed books: C14th- Group I : 2 Engraved printers’ devices; engraved title pages: c1500- Group I : 3-6 Printing, publishing, bookselling: c1700- Group II : 1-2 Private presses: c1820- Group II : 3-4 Typography & fine printing: C20th Group III : 1 Royal College of Art: c1950- Group III : 2 Double Crown Club : c1950- Group III : 3 Berthold Wolpe Group III : 4 John Lewis Group IV : 1 Paper, ink, stationery: c1800- Group IV : 2 Publishers’ sample books: c1820-1880 Group IV : 3 Photography: c1860- Group V : 1-3 Engraved & printed titles & dedications for atlases : c1500- ©University of Reading 2011 Friday 21 January 2011 Page 1 Special Collections Service Library Group V : 4 Portraits: c1670-1870