The Dual Banking System in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edmonton+City+1982+Mar+Sa+To+

RUT-flYL EDMONTON 680 Riizyeki WA10546'8SAve.. ..3..... ..439-2435 'Rir^ 8602-1102099Ava. 488-9852 RYCON WASTE OIL CO LTD RiK^i.Z2lGardwCrShPk 464-4684 M101-1064579 Ava 433-5780 Spruca.Greve..962-3000 VVilliam J10940 7S Aw. 436^757 l6lZ3^SisU9918 ITIAAve 4584570 l^knM A11940141 St 455-9353 Rycroft K 311-15504 84 Ava..: 489-8809 ftutledg^madsaac M H RVmiPPLYLTD j^an^ J 9532lOOASt...:. 426-3131 l^croft SystemsLtd 246^14615101 S«.. 456^1242 1S740 Sbiy Rn Rd..'483^701 Mike 11317103St 474-1779 4 Unlhorpe RdSp Si .962-8235 Rutley Mrs B 419-T0160 isi St.......484-7682 42l099St 468-4294 l^'P53-2024 57a 462-2715 RydallWilliam6 AmhaistCra Mb....458-7241 Rutley Cflfford i(»6i i36Si...........4^2209 Rntdi^ Nick 9847 75 Ava :...... 433-0931 I^ P201-770498St 439-9504 Rydberg W112-87 StiiiingRd. t4Sif699B| Rutl9 0304-9210149St...' 484^^^^ Riris tu'n6il4 lOesi..... 438-1117 1^P16-10245116a 488-8994 l^eRAl151537AAve Rtttl^WssosilASt...;... 434-4434 R-W1yr;Pefsanh«ISeniices ' l^ai»;p14735 51Ava 435-5758 I^en Prank 9316161 a.... RUTLEY W BYRONLawyr 104-9924106St.. 423-9995 RyanPJ 20 GoodridgeDiaAlb...... 458^1574 5^enG152268t Ava.:..... '719-10136100§l.'.424-8830. RMrisibaDZA^t? 11281.. .*.•..'.'439-5760'^: l^tpj 109461583 489^4078 I^en Per8005162a:..!... 489^91 RutsatziK202-11S30124a...........455-1^ ^11^13943119Ava... .454^0165' Ryan PatlSSKomestaadCr... 475-7269 l^er-rSee also Rider • RlttSCllEl051374Ave '4^-1972 R^'DiriiniS njonrairmrrroresiuiDvestAlb.tba-Mia »ri mom lincM' RutschF 204-14507 77 a..... 473-3142 51SPaikiahdMead0««Sp6r.. 962-4766 RyanPatrickRyw Patrick77N7 ForestGalaxyGfove'aWay ShPk.Alb . 464-0254458-3415 5^!^nm nrf'n ^ Riitscb Ll03-l240982a..............474-9926 RyaUil006-44^i08a 434-1163 RyanPaui4l LomaCraAlb 458-6026 S2 S? .^.1 ROtscliLenhaitl'29Waiv»iokRd..,....456-1461 ^^1L40l-8920ieSa........484-0666.1^rPeiTyi08-ll24Sli7a 453-5219 52®'^! -^1 RutecbWalter - 'I^lsKen 13504136Ava 455-7648 Ryan-PeterDSSGraarCraAb.- 458-9150 •S'?' 166GraHdmeadowCr...463-7406463-7406 Ryan A301-10434125a 451-2090 Ryan RA1131157a ... -

Recommendation on Minimum Receiver Technical Requirements for the Reception of DVB-T2 Signal in the Republic of Croatia1

Recommendation on minimum receiver technical requirements for the reception of DVB-T2 signal in the Republic of Croatia1 Disclaimer Only the Croatian version of this document is to be considered official and used as a reference. 1 This document is a recommendation issued by the Croatian Regulatory Authority for Network Industries and it is therefore not binding. CROATIAN REGULATORY AUTHORITY FOR NETWORK INDUSTRIES Roberta Frangeša Mihanovića 9, HR-10110 Zagreb, Croatia / OIB: 87950783661 / Phone: +385 (0)1 7007 007, Fax: +385 (0)1 7007 070 / www.hakom.hr 2 List of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1. Background ...................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2. Scope ................................................................................................................................................ 5 1.3. Definitions ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. Document History ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.5. References ........................................................................................................................................ 7 1.6. Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................. -

Template CAJ/67 ENGLISH

F CAJ/68/6 ORIGINAL : anglais DATE : 6 septembre 2013 UNION INTERNATIONALE POUR LA PROTECTION DES OBTENTIONS VÉGÉTALES Genève COMITÉ ADMINISTRATIF ET JURIDIQUE Soixante-huitième session Genève, 21 octobre 2013 BASES DE DONNÉES D’INFORMATION DE L’UPOV Document établi par le Bureau de l’Union Avertissement : le présent document ne représente pas les principes ou les orientations de l’UPOV 1. Le présent document vise à présenter des propositions relatives au programme d’améliorations de la base de données sur les variétés végétales (base de données PLUTO) et à faire rapport sur l’intention du Bureau de l’Union de réaliser une enquête auprès des membres de l’Union quant à leur utilisation des bases de données aux fins de la protection des obtentions végétales, ainsi que leur utilisation des systèmes de dépôt électronique des demandes. 2. Toujours en ce qui concerne les propositions concernant le programme d’améliorations de la base de données PLUTO, il est rappelé qu’une proposition faite durant l’exposé présenté par l’Office communautaire des variétés végétales de l’Union européenne (OCVV) à la soixante-septième session du Comité administratif et juridique (CAJ), tenue à Genève le 21 mars 2013, d’envisager la possibilité d’élaborer un moteur de recherche des similitudes pour l’UPOV à des fins de dénomination variétale, sur la base du moteur de recherche de l’OCVV, est examinée dans le document CAJ/68/9 “Possibilité d’élaboration d’un outil de recherche de similarité pour l’UPOV aux fins de la dénomination variétale”. Table des matières PROPOSITIONS RELATIVES AU PROGRAMME D’AMÉLIORATIONS DE LA BASE DE DONNÉES PLUTO ............................................................................................................................................ -

A Commercial Carbonaceous Anode with A-Si Layers by Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition for Lithium Ion Batteries

Article A Commercial Carbonaceous Anode with a-Si Layers by Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition for Lithium Ion Batteries Chao-Yu Lee 1, Fa-Hsing Yeh 2 and Ing-Song Yu 2,* 1 Department of Materials Science and Engineering, National Formosa University, Yunlin 632, Taiwan; [email protected] 2 Department of Materials Science and Engineering, National Dong Hwa University, Hualien 974301, Taiwan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-3-890-3219 Received: 12 May 2020; Accepted: 9 June 2020; Published: 11 June 2020 Abstract: In this study, we propose a mass production-able and low-cost method to fabricate the anodes of Li-ion battery. Carbonaceous anodes, integrated with thin amorphous silicon layers by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition, can improve the performance of specific capacity and coulombic efficiency for Li-ion battery. Three different thicknesses of a-Si layers (320, 640, and 960 nm), less than 0.1 wt% of anode electrode, were deposited on carbonaceous electrodes at low temperature 200 ◦C. Around 30 mg of a-Si by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) can improve the specific capacity ~42%, and keep coulombic efficiency of the half Li-ion cells higher than 85% after first cycle charge-discharge test. For the thirty cyclic performance and rate capability, capacitance retention can maintain above 96%. The thicker a-Si layers on carbon anodes, the better electrochemical performance of anodes with silicon-carbon composites we get. The traditional carbonaceous electrodes can be deposited a-Si layers easily by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition, which is a method with high potential for industrialization. -

Babel, a Multilingual Package for Use with LATEX's Standard Document

Babel, a multilingual package for use with LATEX’s standard document classes∗ Johannes Braams Kersengaarde 33 2723 BP Zoetermeer The Netherlands [email protected] Printed May 28, 2005 Abstract The standard distribution of LATEX contains a number of document classes that are meant to be used, but also serve as examples for other users to create their own document classes. These document classes have become very popular among LATEX users. But it should be kept in mind that they were designed for American tastes and typography. At one time they contained a number of hard-wired texts. This report describes babel, a package that makes use of the new capabilities of TEX version 3 to pro- vide an environment in which documents can be typeset in a non-American language, or in more than one language. Contents core of babel and the lan- guage definition files 11 1 The user interface 5 6.1 Support for active char- 1.1 Languages supported by acters . 13 Babel ............ 6 6.2 Support for saving macro 1.2 Workarounds . 7 definitions . 13 2 Changes for LATEX 2ε 7 6.3 Support for extending macros . 14 3 Changes in Babel version 3.7 8 6.4 Macros common to a number of languages . 14 4 Changes in Babel version 3.6 9 5 Changes in Babel version 3.5 10 7 Compatibility with german.sty 14 6 The interface between the 8 Compatibility with ngerman.sty 15 ∗During the development ideas from Nico Poppelier, Piet van Oostrum and many others have been used. -

Template TC/48 ENGLISH

F CAJ/66/4 ORIGINAL : anglais DATE : 20 septembre 2012 UNION INTERNATIONALE POUR LA PROTECTION DES OBTENTIONS VÉGÉTALES Genève COMITÉ ADMINISTRATIF ET JURIDIQUE Soixante-sixième session Genève, 29 octobre 2012 BASES DE DONNÉES D’INFORMATION DE L’UPOV Document établi par le Bureau de l’Union 1. Le présent document a pour objet de faire rapport sur les faits nouveaux concernant la base de données GENIE, le système de codes UPOV et la base de données sur les variétés végétales. BASE DE DONNÉES GENIE .............................................................................................................................2 SYSTÈME DE CODES DE L’UPOV...................................................................................................................2 BASE DE DONNÉES SUR LES VARIÉTÉS VÉGÉTALES ...............................................................................2 GÉNÉRALITÉS ....................................................................................................................................................2 VERSION WEB DE LA BASE DE DONNÉES SUR LES VARIÉTÉS VÉGÉTALES (SECTION 6 DU PROGRAMME)...................3 Informations sur la dernière date de présentation par les fournisseurs de données................................................... 3 Règles de recherche................................................................................................................................................... 3 Fonction de sauvegarde des paramètres de recherche............................................................................................. -

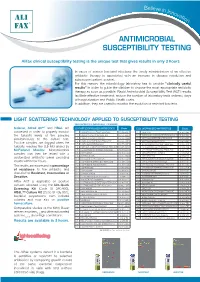

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Bel ieve in Inno vat ion ANTIMICROBIAL SUSCEPTIBILITY TESTING Alifax clinical susceptibility testing is the unique test that gives results in only 3 hours In cases of serious bacterial infections the timely administration of an effective antibiotic therapy is associated with an increase in disease resolution and subsequent patient survival. For this reason, the microbiology laboratory has to provide "clinically useful results" in order to guide the clinician to choose the most appropriate antibiotic therapy as soon as possible. Rapid Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test (AST) results facilitate effective treatment, reduce the number of laboratory tests ordered, days of hospitalization and Public Health costs. In addition, they are useful to monitor the evolution of resistant bacteria. LIGHT SCATTERING TECHNOLOGY APPLIED TO SUSCEPTIBILITY TESTING EACH ANTIBIOTIC IS INDIVIDUALLY MARKED* Sidecar, Alfred 60AST and HB&L are EUCAST LYOPHILISED ANTIBIOTICS Code CLSI LYOPHILISED ANTIBIOTICS Code conceived in order to properly monitor 1 AMIKACIN ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 956-AMK 1 AMIKACIN SI 801-AMK the turbidity levels of the samples 2 AMIKACIN PSEUDOMONAS NN) SI 978-AMK 2 AMOXICILLIN-CLAVULANATE STAPHYLOCOCCI SI 802-AMC simultaneously to the culture test. 3 AMIKACIN STAPHYLOCOCCI SI 981-AMK 3 AMPICILLIN ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 803-AMP 4 AMPICILLIN ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 954-AMP 4 AMPICILLIN ENTEROCOCCI SI 804-AMP Positive samples are fl agged when the 5 AMPICILLIN ENTEROCOCCI SI 955-AMP 5 AZTREONAM ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 805-ATM turbidity reaches the 0.5 McFarland by 6 AMPICILLIN-SULBACTAM ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 997-AMS 6 AZTREONAM PSEUDOMONAS SI 806-ATM McFarland Monitor. Monomicrobial 7 AZTREONAM ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 957-ATM 7 CEFOTAXIME ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 807-CTX samples can then be tested with a 8 CEFOTAXIME SI 959-CTX 8 CEFOXITIN STAPH. -

Ii. Qc Summary E.P.A

II. QC SUMMARY E.P.A. CASE NO. __i A. Surroaate % Recovery Summary • D, DFTPP Performance Summary B. Reagent BlanK Summary • E. BFB Performance Summary C. Matrix Spike Duplicate/ Recovery Summary 013247 A. Surrogate % Recovery Summary Surrogate compounds are added to each sample prior to extraction and analysis ol Its various fractions, Trie recovery ot surrogates la a measure ol extraction efficiency ol classes ol compounds, II surrogate recoveries are outside acceptance criteria, the logic applied Is described In I-D, Decision Tree Process, 013243 HP WII Bs* li PP-rii iW-^i'^*S?§*^^^S?'?^>?*ni F-i^^.rt-'jti"*.*-*^ i r r i> r r rr i1 ri;,'•*"*i i i* FI»I i« i* J——N Tpf i IA$,1^ vjrf US r >j '•«**! 311 • i ! *«« iM^M ssI'ls ifiq ?»!Sl!»i_ WF K nWte ii «4*v "" •••-•* *g '* M< 4> q sir ** > iiil VS v> ' VI \ in , !l|P / ?«'» ^ r «-, F- 013252 ss SB ' »!•» = ? * Sr a' ~ • i™ K 3 i i i to •* .,=> CTBJ«£i £.IT - ? ?«i* :"B (2 ;,|, I I -:,-;!: I . * :" 1 I 1 o II 3 S 11 x »3i r=n •0•2 (8 IPS m 0132157 C. Matrix Spike Duplicate/Recovery Summary Representative compounds lor each traction are spiked Into allquots ol samples selected lor spiking. The recoveries and precision lor these spiked compounds are calculated and reported on the EPA-deslgnated form, Corrections are made for dilutions and for non- standard sample sizes, An additional column has been added to the iiPA form to Include concentrations ol spike compounds In original, unsplked, samples; these are subtracted Irom the concentrations detected In the spiked samples, Associated samples are listed lor each spiked set ot sample fractions; these represent samples processed with the spiked set, at the frequency of one set for each fraction per case, or at least per 20 samples. -

(DVB); Subtitling Systems

Digital Video Broadcasting (DVB); Subtitling Systems DVB Document A009 Nov 2017 This page is left intentionally blank 3 Contents Intellectual Property Rights ................................................................................................................................ 5 Foreword............................................................................................................................................................. 5 1 Scope ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 2 References ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Normative references ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Informative references ....................................................................................................................................... 6 3 Definitions and abbreviations ................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Definitions ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................................... -

NDIGORP015602.Pdf

S u it 4 .w rz e ś n ie 1611 roku oddoł Jacek Przybylak! Jerzemu Barnas iowi Bondtklemu bibljotekę a powinszowaniem sukcesu n. admini stra cji tejfee,Jeden jni&ł la t 4 3 , d r o g i 5 5 , - ier asy więc nie był r>ierv,r„łsej a ło d o 5c i , d .rugi. nie tyle wiekiem at< ngany,ahy mógł my* $1©<5 o emeryturze#! jednak o a tę pił zniechęcony,be nie wiodło alę z- wiodoatv;u jego #• Objęł Bandtkie bib 1 joto kę z drogiej ręki,bo dozorował nię od czerwce do sierpnia proi. liędz Kadrowi©*,, i do przybycie Sond ki©??© i ja i nt aoa wstęp opotki ł& Bandtkieg© nic przyjemnoed,id dozór Szkoły O lan ej dni> 16*^r»esini;, nukazał temu!,by ze swej pensji r&a&ner.-cję Budrewicz® zapłacił*Ustnie mu poleoono,by dał 150 ałp. Kadrowi es o d p ią ł w pr*frayłfcę,id nt grodu nulody się w stosunku B uo złp.rocznej penaji pobier noj jt ko zontępoy urzę dowemu,więc akt niniejszy uw<: -4& za ufront sobie wyrządzony, z ozem udu się wydej, Pienlędse odesłał. Sol jego był do szkoły,, nie do a.ndtkiego,a którym się pray- jtz n lł. Cała sprawo ©pa-rłs się © Izbę Bdnki cyjnę,bc Dozór nio prayjęł o fU ry B&idtkisgo, który ehcii ł Budrewiczowi odstępie pł* eę dwornie zięc snę, Bł not kle, ad* Ję0 spr wę ze at< nu biblioteki dnia S.grudni: 1011 r , o pow u da, i i został bi bije tekę w a: 1 1 Jagiellońskiej w tt kim n ieład zie,ii n&wet rewlzyi czynić nie mógł,Podał petem pltn in strukcji blbljotecznej.ziepukejenia potrzeb bibliotecznych i za- kum& driieł z udsl łom profesorów. -

Videotex Systems and Services

NTIA-Report-80-50 VI DEOTEX Systems and Services L.R. Bloom A.G. Hanson R. F. Li nfield D.R. Wortendyke u.s. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Philip M. Klutznick, Secretary Henry Geller, Assistant Secretary for Communications and Information October 1980 PREFACE This report describes a number of new non-speech telecommunication services soon to be offered to the American public. Videotex is the generic term for systems that transmit text and graphics to the business or home viewer by means of signals carried over a telephone line, cable, or any of the TV or radio broad cast channels. A television receiver equipped with the necessary decoding and memory circuit provides the home user with access to hundreds of "pages" of selected information for viewing by the customer for one-way non-interactive systems. In the broadcast modes of operation, the customer may select by "book and page ll from a large selection of subjects being broadcast at some specific time. Interactive Videotex systems allow the subscriber to interrogate a data center by telephone and to select, from hundreds of thousands of stored pages, that information of particular interest to the user. The report in its present form contains a brief discussion concerning individ ual types of services, but primary emphasis is upon the need for a highly critical evaluation of a whole group of technological building blocks which already exist. We already have all the pieces provided for user-oriented national or international computer-based communications and information networks. The terminals are as close to our office or home as are the ubiquitous telephones, and as viewable as the (almost) standard home television receivers. -

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Believe in In nova tion ANTIMICROBIAL SUSCEPTIBILITY TESTING Alifax clinical susceptibility testing is the unique test that gives results in only 3 hours In cases of serious bacterial infections the timely administration of an effective antibiotic therapy is associated with an increase in disease resolution and subsequent patient survival. For this reason, the microbiology laboratory has to provide "clinically useful results" in order to guide the clinician to choose the most appropriate antibiotic therapy as soon as possible. Rapid Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test (AST) results facilitate effective treatment, reduce the number of laboratory tests ordered, days of hospitalization and Public Health costs. In addition, they are useful to monitor the evolution of resistant bacteria. LIGHT SCATTERING TECHNOLOGY APPLIED TO SUSCEPTIBILITY TESTING EACH ANTIBIOTIC IS INDIVIDUALLY MARKED AST Sidecar, Alfred 60 and HB&L are EUCAST LYOPHILISED ANTIBIOTICS Code CLSI LYOPHILISED ANTIBIOTICS Code conceived in order to properly monitor 1 AMIKACIN ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 956-AMK 1 AMIKACIN SI 801-AMK the turbidity levels of the samples 2 AMIKACIN PSEUDOMONAS NN) SI 978-AMK 2 AMOXICILLIN-CLAVULANATE STAPHYLOCOCCI SI 802-AMC simultaneously to the culture test. 3 AMIKACIN STAPHYLOCOCCI SI 981-AMK 3 AMPICILLIN ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 803-AMP 4 AMPICILLIN ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 954-AMP 4 AMPICILLIN ENTEROCOCCI SI 804-AMP Positive samples are flagged when the 5 AMPICILLIN ENTEROCOCCI SI 955-AMP 5 AZTREONAM ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 805-ATM turbidity reaches the 0.5 McFarland by 6 AMPICILLIN-SULBACTAM ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 997-AMS 6 AZTREONAM PSEUDOMONAS SI 806-ATM McFarland Monitor. Monomicrobial 7 AZTREONAM ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 957-ATM 7 CEFOTAXIME ENTEROBACTERIACEAE SI 807-CTX 8 CEFOTAXIME SI 959-CTX samples can then be tested with a 8 CEFOXITIN STAPH.