Migration and the Language Border1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utveckling Av En Kartbaserad Metod För Uppföljning Av Muddringar I Raseborg

Utveckling av en kartbaserad metod för uppföljning av muddringar i Raseborg Frida Ringwall Examensarbete för Yrkeshögskolan Novia (YH)-examen Utbildningsprogrammet för Skogsbruk och miljö Raseborg 2013 EXAMENSARBETE Författare: Frida Ringwall Utbildningsprogram och ort: Skogsbruk och miljö, Raseborg Inriktningsalternativ/Fördjupning: Miljöplanering Handledare: Eva Sandberg-Kilpi och Mikael Kilpi Titel: Utveckling av en kartbaserad metod för uppföljning av muddringar i Raseborg _____________________________________________________________________ Datum 26.11.2013 Sidantal 30 Bilagor 5 _____________________________________________________________________ Sammanfattning Examensarbetets huvudsakliga mål var att med hjälp av GIS skapa en karta över muddringar för området Raseborg. Som beställare fungerade forsknings- och utvecklingsinstitutet Aronia. Förarbetet gjordes under en praktiktid under sommaren 2012 och själva examensarbetet gjordes under hösten 2013. Under sommaren 2012 lades data om muddringsanmälningarna in i programmet SpatialWeb och under hösten 2013 sammanfattades denna data som en karta i ArcGIS 10.1. Denna karta ger en klar översikt över den geografiska omfattningen av muddringar; vilket år muddringarna anmälts, var de är belägna och hur stora de uppskattningsvis är. Tidsperioden som undersöktes var åren 2007 till 2011. Vidare undersökning gjordes för specifika fall i Bölsviken och Bredviken i Bromarv, Raseborg. Metoden som användes för utvecklandet av kartan går också att tillämpa på andra områden. Kartan kan dessutom vara -

Population Structure 2009

Population 2010 Population Structure 2009 Number of persons aged under 15 in Finland’s population lowest in over 100 years According to Statistics Finland’s statistics on the population structure there were 888,323 persons aged under 15 in Finland’s population at the end of 2009. The number is the lowest since 1895. The size of the population under the age of 15 has been decreasing continuously since 1994. At the end of 1977, there were still one million persons aged under 15 in the Finnish population. The size of the population under the age of 15 was at its largest in 1959 when it was 1.35 million. Number of persons aged under 15 in Finland’s population in 1875–2009 On 31 December 2009, the total population of Finland was 5,351,427 in which 2,625,067 were men and 2,726,360 women. In the course of 2009, Finland’s population grew by 25,113 persons. For the third successive year migration gain from abroad contributed more to the increase of population than natural growth. During 2009, the number of persons aged 65 and over in the population increased by good 18,000 and totalled 910,441 at the end of 2009. The largest age cohort in Finland’s population was persons born in 1948. At the end of 2009, they numbered 82,738. Persons over 100 years of age numbered 566, of whom 82 were men and 484 women. Demographic dependency ratio highest in Etelä-Savo and lowest in Uusimaa The demographic dependency ratio, that is the number of under 15 and over 65-year-olds per 100 working age persons was 50.6 at the end of 2009. -

Labour Market Areas Final Technical Report of the Finnish Project September 2017

Eurostat – Labour Market Areas – Final Technical report – Finland 1(37) Labour Market Areas Final Technical report of the Finnish project September 2017 Data collection for sub-national statistics (Labour Market Areas) Grant Agreement No. 08141.2015.001-2015.499 Yrjö Palttila, Statistics Finland, 22 September 2017 Postal address: 3rd floor, FI-00022 Statistics Finland E-mail: [email protected] Yrjö Palttila, Statistics Finland, 22 September 2017 Eurostat – Labour Market Areas – Final Technical report – Finland 2(37) Contents: 1. Overview 1.1 Objective of the work 1.2 Finland’s national travel-to-work areas 1.3 Tasks of the project 2. Results of the Finnish project 2.1 Improving IT tools to facilitate the implementation of the method (Task 2) 2.2 The finished SAS IML module (Task 2) 2.3 Define Finland’s LMAs based on the EU method (Task 4) 3. Assessing the feasibility of implementation of the EU method 3.1 Feasibility of implementation of the EU method (Task 3) 3.2 Assessing the feasibility of the adaptation of the current method of Finland’s national travel-to-work areas to the proposed method (Task 3) 4. The use and the future of the LMAs Appendix 1. Visualization of the test results (November 2016) Appendix 2. The lists of the LAU2s (test 12) (November 2016) Appendix 3. The finished SAS IML module LMAwSAS.1409 (September 2017) 1. Overview 1.1 Objective of the work In the background of the action was the need for comparable functional areas in EU-wide territorial policy analyses. The NUTS cross-national regions cover the whole EU territory, but they are usually regional administrative areas, which are the re- sult of historical circumstances. -

Local Government Tax Revenues in Finland Tallinn 13.11.2018

Onnistuva Suomi tehdään lähellä Finlands framgång skapas lokalt Local government tax revenues in Finland Tallinn 13.11.2018 Henrik Rainio, Director, Municipal Finances The Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities Municipalities in Finland • The responsibility of municipalities for social services, healthcare, educational and cultural services, public infrastructure as well as the organisation of other welfare services is extremely significant by international and also European standards. • Local government accounts for two-thirds of public consumption in Finland. • The ratio of the total expenditure of local government to GDP has been about 20% in recent years. • Local government employs about one fifth of the total Finnish labour force. • Municipalities have the right to tax the earned income of their inhabitants (municipal income taxation) and municipalities are paid tax on the basis of the value of real property (tax on real property). Municipalities are also entitled to a share of corporate income tax. 2 Onnistuva Suomi tehdään lähellä Finlands framgång skapas lokalt 14.11.2018 Total municipal sector expenditure and income for 2017 Salaries and Social welfare Tax revenues 51 % wages 36 % and health care 22,6 billion € 15,9 billion € 48 % 21,1 billion € Income tax 43 % Corporate tax 4 % Social security funds Real estate tax 4 % and pensions 10 % Purchase of goods 8 % Education and State grants 19 % Purcahse of Culture 31 % 8,5 billion € services 22 % 13,6 billion € Sales of goods and Subsidies 5 % services 21 % Loan costs 5 % Other 15 % 9,2 billion € Investments 11 % 6,6 billion € Borrowing 5 %, 2,4 mrd. € Financing 6 %, 2,7 billion € Other 3 % Other revenues 4 %, 1,8 mrd. -

District 107 F.Pdf

Club Health Assessment for District 107 F through December 2020 Status Membership Reports Finance LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Activity Account Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Report *** Balance Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater report in 3 more than of officers thatin 12 months within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not haveappears in two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active red Clubs more than two years old M,MC,SC 20649 ÄHTÄRI 03/31/1965 Active 10 0 0 0 0.00% 10 1 IP 0 32745 ÄHTÄRI/OULUVESI 09/22/1976 Active 24 0 0 0 0.00% 25 1 N 0 20599 ALAHÄRMÄ 10/11/1961 Active 31 0 0 0 0.00% 31 1 N 6 MC,SC 20650 ALAJÄRVI/JÄRVISEUTU 02/26/1960 Active 34 0 0 0 0.00% 34 0 N 0 VP,MC,SC 20651 ALAVUS 03/06/1964 Active 16 0 0 0 0.00% 17 0 2 9 104719 ALAVUS/KUULATTARET 02/11/2009 Active 16 1 2 -1 -5.88% 20 5 1 N 3 M,MC,SC 36146 ALAVUS/SALMI 10/16/1978 Active 20 0 0 0 0.00% 21 1 N 19 MC,SC 20597 EVIJÄRVI 10/17/1963 Active 35 0 0 0 0.00% 38 0 N 0 MC,SC 20600 ILMAJOKI 02/25/1964 Active 26 1 0 1 4.00% 27 1 N 3 44303 ILMAJOKI/ILKKA 10/31/1984 Active 35 1 0 1 2.94% 34 0 N 0 $96.15 M,MC,SC 67723 ILMAJOKI/VILJAT 04/11/2003 Active 23 1 1 0 0.00% 21 13 1 N 2 MC 20601 -

Lahti-Kovola-Rataosuuden Kulttuurihistoriallisten Kohteiden

Väyläviraston julkaisuja 3/2021 LAHTI–KOUVOLA-RATAOSUUDEN KULTTUURIHISTORIALLISTEN KOHTEIDEN INVENTOINTI Roosa Ruotsalainen Lahti–Kouvola-rataosuuden kulttuurihistoriallisten kohteiden inventointi Väyläviraston julkaisuja 3/2021 Väylävirasto Helsinki 2021 Kannen kuva: Lepomaan hautausmaan kiviaitaa. Kuva: Roosa Ruotsalainen Verkkojulkaisu pdf (www.vayla.fi) ISSN 2490-0745 ISBN 978-952-317-838-0 Väylävirasto PL 33 00521 HELSINKI Puhelin 0295 34 3000 Väyläviraston julkaisuja 3/2021 3 Roosa Ruotsalainen: Lahti–Kouvola-rataosan kulttuurihistoriallinen inventointi. Väy- lävirasto. Helsinki 2021. Väyläviraston julkaisuja 3/2021. 67 sivua ja 3 liitettä. ISSN 2490- 0745, ISBN 978-952-317-838-0. Asiasanat: rautatiet, inventointi, kulttuuriperintö Tiivistelmä Tässä selvityksessä kartoitettiin Lahden ja Kouvolan välisen radan kulttuurihisto- riallista merkitystä ja selvitettiin radan rakenteiden ja siihen liittyvien rakennusten ja erilaisten kohteiden historiaa. Tavoitteena työssä oli tämän lisäksi kerätä koke- muksia tulevia ratainventointeja varten. Selvitys on jatkoa suoritetuille sisävesi- inventoinneille. Selvitys suoritettiin arkistotutkimuksen ja maastokäyntien avulla. Maastokäynneillä kartoitettiin 70 erilaista kohdetta, kuten asema-alueet, tasoristeyspaikat, taito- rakenteet, vanhat ratapohjat ja sivuradat sekä ratavartijan tupien tontit. Tarkiste- tuista kohteista valittiin 31 kohdetta, joista tehtiin kohdekortit. Selvityksessä valituille kohteille tehtiin arvoluokitus kohdekortteihin. Kohteet arvo- tettiin Väyläviraston arvokohteiden -

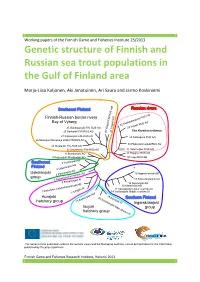

Julkaisusarjan Nimi

Working papers of the Finnish Game and Fisheries Institute 25/2013 Genetic structure of Finnish and Russian sea trout populations in the Gulf of Finland area Marja-Liisa Koljonen, Aki Janatuinen, Ari Saura and Jarmo Koskiniemi M A S U R O - S A O U Finnish-Russian border rivers N R I o A r u F i p an i l k ka Bay of Vyborg k k O o o A j u o K S j RU o 32 ki a r jo l i Ino i 29 25 Rakkolanjoki FIN-RUS AO V V 1 4 The Karelian Isthmus 23 Santajoki FIN-RUS AO 2 2 27 Kilpeenjoki FIN-RUS AO 28 Notkopuro RUS AO 26 Mustajoki Kananoja 2006 FIN-RUS AO 30 Pikkuvammeljoki RUS AO 26 Mustajoki FIN-RUS AO 22 Urpalanjoki FIN-RUS AO 31 Vammeljoki RUS AO 11 Siuntionjoki AO 33 Rajajoki RUS AO 9 Karjaanjoki Mustionjoki AO 34 Luga RUS AO O njoki A 3 Purila i AO lanjok Uske 5 oki AO Uskelanjoki mionj O 10 Ingarskilanjoki AO 2 Pai oki A rniönj group oki Pe skonj 18 Koskenkylanjoki AI 7 Ki joki AI skarsin 8 Fi 15 Sipoonjoki AO M koski A 12 Mankinjoki AO rtanon Latoka AI 14 Vantaanjoki Lower reaches AI njoki joki Kisko ura 7 1 A 14 Vantaanjoki Middle reaches AI AM oki 1 Aurajoki onj 2 9 K po 0 S ym Es u ijo hatchery group 13 mm ki A an I Ingarskilanjoki jok i M Isojoki ai group n s tre hatchery group am AI The content of the publication reflects the authors views and the Managing Authority cannot be held liable for the information published by the project partners. -

Sisulisätilastot 2018

Lahden Seudun Yleisurheilu r.y. Sisulisätilastot 2018 Huom! Juoksulajien käsiajat ilmoitettu lisämainintana vain, jos ne ovat 40 - 200 m matkoilla yli 0,24 s ja 300 m tai sitä pidemmillä matkoilla yli 0,14 s ”parempia” kuin kunkin automaattisella ajanotolla saavutetut tulokset. Tuulilukemat on ilmoitettava pikajuoksuista ja pituussuuntaisista hypyistä 14 v. sarjasta alkaen ylöspäin, muuten kirjattu ”ei tuulilukemaa” -otsikon alle. Sisäratatulokset mainittu, jos ne ovat a.o. urheilijan ulkoratatuloksia paremmat. Tilaston laatinut: Aulis Tiensuu Pahkakatu 4 as 4 15950 LAHTI p. 040 - 5511 030 mailto: [email protected] Tilaston sekä piiriennätystulosten mahdolliset korjaukset ja täydennykset suoraan tekijälle, kiitos 1 POJAT 40 m P 10 6,53 Verneri Marttila 2008 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/R 21.08. Hip 6,66 Alex Kurkela 2008 Lahti Lahti/R 21.08. Hip 6,69 Jesse Korhonen 2008 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/R 21.08. Hip P 9 PE 6,3 Ville Suorajärvi 1994Nastolan Naseva Nastola 12.08.2003 6,57 Joska Tommola 1999 Asikkalan Raikas Kuhmoinen16.08.2008 6,55 i Karim Echahid 2001 Lahden Ahkera Espoo/O 06.12.2010 6,55 Oskari Syväranta 2009 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/R 10.08.2018 6,55 Oskari Syväranta 2009 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/R 10.08. so 6,64 -0,5 Lahti/R 08.07. kv 6,63 -0,5 Rasmus Rautavirta 2009 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/R 08.07. kv 6,94 i Ilkka Kallioniemi 2009 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/P 02.04. pm 7,04 Lahti/N 17.05. pk 6,98 Niilo Kemppainen 2009 Nastolan Naseva Iitti/K 17.07. pm 7,07 +1,6 Kouvola 28.07. -

Lahden Seudun Liikennetutkimus 2010

Lahden seudun liikennetutkimus 2010 Lahden seudulla tehtiin keväällä 2010 laaja liikennetutkimus, jossa selvi- Liikennetutkimuksen ovat toteuttaneet tettiin henkilöhaastatteluilla, ajoneuvoliikenteen tutkimuksilla ja liikenne- Uudenmaan ELY-keskus, Lahden kaupunki, laskennoilla seudun asukkaiden liikkumistottumuksia sekä ajoneuvolii- Asikkalan kunta, Hollolan kunta, Nastolan kenteen, jalankulun ja pyöräilyn määrää. Liikennetutkimusalueeseen kunta ja Orimattilan kaupunki sekä Päijät- kuuluivat Asikkala, Hollola, Lahti, Nastola ja Orimattila. Vastaava liikenne- Hämeen liitto maakunnan kehittämis- tutkimus on viimeksi toteutettu Lahden seudulla vuosina 1996 ja 1982. rahoituksella. Lisätietoja liikennetutkimuk- sesta on saatavilla internetissä osoitteessa Seudun asukkaat tekevät yli 500 000 matkaa http://www.paijat-hame.fi/liikennetutkimus päivittäin 1 100 ajon./vrk 63 % matkoista suuntautui Lahden seudulle ja 37 % kulki Kaiken kaikkiaan seudun yli 5-vuotiaat asukkaat seudun läpi tekevät arkisin noin 520 000 matkaa, joista suurin 6 700 ajon./vrk osa on oman kunnan sisäisiä matkoja. Matkalla 49 % matkoista suuntautui Lahden tarkoitetaan siirtymistä paikasta toiseen kävellen seudulle ja 61 % kulki 2 600 ajon./vrk seudun läpi tai jollain kulkuneuvolla, esimerkiksi kotoa kaup- 73 % matkoista suuntautui Lahden paan, kotoa työpaikalle tai kaupasta kotiin. Näi- seudulle ja 27 % kulki seudun läpi 2 500 ajon./vrk den matkojen lisäksi seudun ulkopuolella asuvat 64 % matkoista suuntautui Lahden tekevät matkoja Lahden seudulle ja myös Lahden seudulle -

Lions Club Ekenäs 50 År

Lions Club Ekenäs 50 år Lions Club Ekenäs Tryckplats: Ekenäs Tryckeri 2008 Presidentens förord Lions Club Ekenäs firar 50-årsjubileum i oktober 2008. Björn Björkvall, lektor i religion och filosofi vid Ekenäs samlyceum, tog initiativet till att grunda LC Ekenäs. Den 1 april 1958 bildades klubben och charterfesten hölls den 25 oktober samma år. Då LC Ekenäs grundades för 50 år sedan stod LC Lohja som fadderklubb. Vid olika jubiléer som hållits i vår klubb har det getts ut historiker. Nu vid 50-årsjubiléet ges den i en ny utformning som benämns jubileumsskrift. Först beskrivs klubbens tillkomst och lionsrörelsens uppkomst i Finland, varefter följer en allmän översikt över Lions Club Ekenäs verksamhet. Därefter berättar den enda kvarvarande chartermed- lemmen Johan Rappe om sina hågkomster. I specialtexter skrivna av lionsbröder som har varit länge med i klubben och i specialintervjuer kan man läsa om olika aktiviteter. Ladylions har sedan början aktivt medverkat i klubbens verksamhet och de har fått en egen text i jubileumsskriften. Jubileumsskriften har sammanställts av Mårten Kevin och för layouten står Kaj Koivumäki. Tack vare befolkningens välvilliga inställning har vi kunnat ha vår mångsidiga verksamhet, vari också har ingått större projekt, såsom den av barnen högt uppskattade Lions Park. Den senaste och fjärde större donationen gäller ljugarbänken som överläts till Ekenäs stad på sommaren inför klubbens 50-årsjubileum. Klas Dahlqvist President i LC Ekenäs Bengt Björkholm 18.1.1927-17.8.2008 LC Ekenäs fick två månader före sitt 50-årsjubileum sorgebu- det att den äldsta, aktiva klubbmedlemmen Bengt Björkholm hade avlidit. Broder Bengt var aktiv inom klubben in i det sista. -

LUETTELO Kuntien Ja Seurakuntien Tuloveroprosenteista Vuonna 2021

Dnro VH/8082/00.01.00/2020 LUETTELO kuntien ja seurakuntien tuloveroprosenteista vuonna 2021 Verohallinto on verotusmenettelystä annetun lain (1558/1995) 91 a §:n 3 momentin nojalla, sellaisena kuin se on laissa 520/2010, antanut seuraavan luettelon varainhoitovuodeksi 2021 vahvistetuista kuntien, evankelis-luterilaisen kirkon ja ortodoksisen kirkkokunnan seurakuntien tuloveroprosenteista. Kunta Kunnan Ev.lut. Ortodoks. tuloveroprosentti seurakunnan seurakunnan tuloveroprosentti tuloveroprosentti Akaa 22,25 1,70 2,00 Alajärvi 21,75 1,75 2,00 Alavieska 22,00 1,80 2,10 Alavus 21,25 1,75 2,00 Asikkala 20,75 1,75 1,80 Askola 21,50 1,75 1,80 Aura 21,50 1,35 1,75 Brändö 17,75 2,00 1,75 Eckerö 19,00 2,00 1,75 Enonkoski 21,00 1,60 1,95 Enontekiö 21,25 1,75 2,20 Espoo 18,00 1,00 1,80 Eura 21,00 1,50 1,75 Eurajoki 18,00 1,60 2,00 Evijärvi 22,50 1,75 2,00 Finström 19,50 1,95 1,75 Forssa 20,50 1,40 1,80 Föglö 17,50 2,00 1,75 Geta 18,50 1,95 1,75 Haapajärvi 22,50 1,75 2,00 Haapavesi 22,00 1,80 2,00 Hailuoto 20,50 1,80 2,10 Halsua 23,50 1,70 2,00 Hamina 21,00 1,60 1,85 Hammarland 18,00 1,80 1,75 Hankasalmi 22,00 1,95 2,00 Hanko 21,75 1,60 1,80 Harjavalta 21,50 1,75 1,75 Hartola 21,50 1,75 1,95 Hattula 20,75 1,50 1,80 Hausjärvi 21,50 1,75 1,80 Heinola 20,50 1,50 1,80 Heinävesi 21,00 1,80 1,95 Helsinki 18,00 1,00 1,80 Hirvensalmi 20,00 1,75 1,95 Hollola 21,00 1,75 1,80 Huittinen 21,00 1,60 1,75 Humppila 22,00 1,90 1,80 Hyrynsalmi 21,75 1,75 1,95 Hyvinkää 20,25 1,25 1,80 Hämeenkyrö 22,00 1,70 2,00 Hämeenlinna 21,00 1,30 1,80 Ii 21,50 1,50 2,10 Iisalmi -

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O.