Revisiting Imaging Features and the Embryologic Basis of Third And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Anatomy As Related to Tumor Formation Book Four

SEER Program Self Instructional Manual for Cancer Registrars Human Anatomy as Related to Tumor Formation Book Four Second Edition U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service National Institutesof Health SEER PROGRAM SELF-INSTRUCTIONAL MANUAL FOR CANCER REGISTRARS Book 4 - Human Anatomy as Related to Tumor Formation Second Edition Prepared by: SEER Program Cancer Statistics Branch National Cancer Institute Editor in Chief: Evelyn M. Shambaugh, M.A., CTR Cancer Statistics Branch National Cancer Institute Assisted by Self-Instructional Manual Committee: Dr. Robert F. Ryan, Emeritus Professor of Surgery Tulane University School of Medicine New Orleans, Louisiana Mildred A. Weiss Los Angeles, California Mary A. Kruse Bethesda, Maryland Jean Cicero, ART, CTR Health Data Systems Professional Services Riverdale, Maryland Pat Kenny Medical Illustrator for Division of Research Services National Institutes of Health CONTENTS BOOK 4: HUMAN ANATOMY AS RELATED TO TUMOR FORMATION Page Section A--Objectives and Content of Book 4 ............................... 1 Section B--Terms Used to Indicate Body Location and Position .................. 5 Section C--The Integumentary System ..................................... 19 Section D--The Lymphatic System ....................................... 51 Section E--The Cardiovascular System ..................................... 97 Section F--The Respiratory System ....................................... 129 Section G--The Digestive System ......................................... 163 Section -

Head and Neck Specimens

Head and Neck Specimens DEFINITIONS AND GENERAL COMMENTS: All specimens, even of the same type, are unique, and this is particularly true for Head and Neck specimens. Thus, while this outline is meant to provide a guide to grossing the common head and neck specimens at UAB, it is not all inclusive and will not capture every scenario. Thus, careful assessment of each specimen with some modifications of what follows below may be needed on a case by case basis. When in doubt always consult with a PA, Chief/Senior Resident and/or the Head and Neck Pathologist on service. Specimen-derived margin: A margin taken directly from the main specimen-either a shave or radial. Tumor bed margin: A piece of tissue taken from the operative bed after the main specimen has been resected. This entire piece of tissue may represent the margin, or it could also be specifically oriented-check specimen label/requisition for any further orientation. Margin status as determined from specimen-derived margins has been shown to better predict local recurrence as compared to tumor bed margins (Surgical Pathology Clinics. 2017; 10: 1-14). At UAB, both methods are employed. Note to grosser: However, even if a surgeon submits tumor bed margins separately, the grosser must still sample the specimen margins. Figure 1: Shave vs radial (perpendicular) margin: Figure adapted from Surgical Pathology Clinics. 2017; 10: 1-14): Red lines: radial section (perpendicular) of margin Blue line: Shave of margin Comparison of shave and radial margins (Table 1 from Chiosea SI. Intraoperative Margin Assessment in Early Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. -

Head and Neck: Summary Stage 2018 Coding Manual V2.0

HEAD AND NECK DEFINITION OF ANATOMIC SITES WITHIN THE HEAD AND NECK Note: Not all sites in the lip, oral cavity, pharynx and salivary glands are listed below. All sites to which a Summary Stage chapter applies are listed at the beginning of the chapter. LIP, ORAL CAVITY and PHARYNX The oral cavity extends from the skin-vermilion junction of the lips to the junction of the hard and soft palate above and to the line of circumvallate papillae below. LIP AND ORAL CAVITY Site ICD-O Description LIPS C00_ Vermilion surface, mucosal lip, labial (mucosa) upper and lower, form the upper and lower anterior wall of the oral cavity. They consist of an exposed surface of modified epidermis beginning at the junction of the vermilion border with the skin and including only the vermilion surface or that portion of the lip that meets the opposing lip. The lips extend from commissure to commissure. COMMISSURE C006 (corner of mouth) is the point of union of upper and lower lips and is part of the lip OF LIP ANTERIOR C02_ (mobile or oral tongue) consists of the freely movable portion of the tongue which 2/3 OF extends anteriorly from the line of circumvallate papillae to the root of the tongue at the TONGUE junction of the floor of the mouth. It is composed of four areas: tip, lateral borders, dorsum, and undersurface or ventral surface (non-villous surface). UPPER GUM C030 (upper alveolar ridge) is the covering mucosa of the alveolar process of the maxilla, extending from the line of attachment of mucosa in the upper gingival buccal gutter to the junction of the hard palate. -

A Retrospective Comparison of Tumor Recurrence and Patient Survival After

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library School of Medicine 1987 A retrospective comparison of tumor recurrence and patient survival after treatment with preoperative radiation therapy and surgery, or surgery and postoperative radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the pyriform sinus and hypopharynx Jesse George Wardlow Jr. Yale University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl Recommended Citation Wardlow, Jesse George Jr., "A retrospective comparison of tumor recurrence and patient survival after treatment with preoperative radiation therapy and surgery, or surgery and postoperative radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the pyriform sinus and hypopharynx" (1987). Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library. 3284. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/3284 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Medicine at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RETROSPECTIVE COMPARISON OF Permission for photocopying or microfilming of purpose of individual scholarly consultation or reference is hereby granted by the author. This permission is not to be interpreted as affecting publication of this work, or otherwise placing -

190.18 - Serum Iron Studies

Medicare National Coverage Determinations (NCD) Coding Policy Manual and Change Report (ICD-10-CM) 190.18 - Serum Iron Studies HCPCS Codes (Alphanumeric, CPT AMA) Code Description 82728 Ferritin 83540 Iron 83550 Iron Binding capacity 84466 Transferrin ICD-10-CM Codes Covered by Medicare Program The ICD-10-CM codes in the table below can be viewed on CMS’ website as part of Downloads: Lab Code List, at http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coverage/CoverageGenInfo/LabNCDsICD10.html Code Description A01.00 Typhoid fever, unspecified A01.01 Typhoid meningitis A01.02 Typhoid fever with heart involvement A01.03 Typhoid pneumonia A01.04 Typhoid arthritis A01.05 Typhoid osteomyelitis A01.09 Typhoid fever with other complications A01.1 Paratyphoid fever A A01.2 Paratyphoid fever B A01.3 Paratyphoid fever C A01.4 Paratyphoid fever, unspecified A02.0 Salmonella enteritis A02.1 Salmonella sepsis A02.20 Localized salmonella infection, unspecified NCD 190.18 January 2021 Changes ICD-10-CM Version – Red Fu Associates, Ltd. January 2021 1 Medicare National Coverage Determinations (NCD) Coding Policy Manual and Change Report (ICD-10-CM) Code Description A02.21 Salmonella meningitis A02.22 Salmonella pneumonia A02.23 Salmonella arthritis A02.24 Salmonella osteomyelitis A02.25 Salmonella pyelonephritis A02.29 Salmonella with other localized infection A02.8 Other specified salmonella infections A02.9 Salmonella infection, unspecified A04.0 Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection A04.1 Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection A04.2 Enteroinvasive Escherichia -

Pitfalls in the Staging of Cancer of the Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Pitfalls in the Staging of Cancer of the Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Amanda Corey, MD KEYWORDS Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma Oropharynx Human papilloma virus Transoral robotic surgery KEY POINTS Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) has a dichotomous nature with 1 subset of the disease associated with tobacco and alcohol use and the other having proven association with human papilloma virus infection. Imaging plays an important role in the staging and surveillance of OPSCC. A detailed knowledge of the anatomy and pitfalls is critical. This article reviews the detailed anatomy of the oropharynx and epidemiology of OPSCC, along with its staging, patterns of spread, and treatment. Anatomic extent of disease is central to deter- tissue, constrictor muscles, and fascia. The over- mining stage and prognosis, and optimizing treat- whelming tumor pathology is squamous cell carci- ment planning for head and neck squamous cell noma (SCC), arising from the mucosal surface. carcinoma (HNSCC). The anatomic boundaries of As the OP contents include lymphoid tissue and the oropharynx (OP) are the soft palate superiorly, minor salivary glands, lymphoma and nonsqua- hyoid bone, and vallecula inferiorly, and circumvel- mous cell tumors of salivary origin can occur.2 late papilla anteriorly. The OP communicates with In understanding spread of disease from the OP, the nasopharynx superiorly and the hypopharynx it is helpful to remember the fascial boundaries and supraglottic larynx inferiorly, and is continuous subtending the OP, to recall the relationship of with the oral cavity anteriorly. The palatoglossus the pharyngeal constrictor muscles with the ptery- muscle forms the anterior tonsillar pillar, and the gomandibular raphe and the deep cervical fascia, palatopharyngeus muscle forms the posterior and to be aware of the adjacent spaces and struc- tonsillar pillar. -

Fistulization Between Stomach and Transverse Colon Because of Nasogastric Feeding Tube

LETTER 89 Fistulization between stomach and transverse colon because of nasogastric feeding tube Mustafa Çelik, Ali Kagan Gokakin, Utku Ozgen, Mustafa Gurkan Haytaoglu Pamukkale University, Gastroenterology Department, 20070 Deni̇ zi, Turkey. To The Editor (NSAIDs) or steroids. Neoplasia is another rare cause. Iatrogenic causes such as nasogastric and orogastric tube Nasogastric tube is commonly used for nasogastric misplacements are extremely rare, despite the frequent decompression, feeding, and gastric lavage. In the gastrointestinal tract, malposition, coiling, or knotting can occur anywhere along the course of the tube, including the pharynx, pyriform sinus, esophagus, stomach, and duodenum (1). Nasogastric tubes can cause gastritis or gastric bleeding because of chronic irritation or pressure necrosis (2). Patients with prior esophageal or gastric surgery have a higher risk for gastrointestinal perforation, and those with facial trauma are at a risk for cribriform plate perforation and intracranial insertion (3-4). However, there are no data regarding gastrocolic fistulization secondary to the use of a nasogastric feeding tube. A 21-year-old female patient, being followed up for cerebral palsy, was admitted to the emergency service because of fecaloid emesis and the drainage of fecaloid content from the nasogastric feeding tube for 2 days. The patient had meningitis when she was 3-month-old and had been followed up for cerebral palsy. It was learned that her percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy catheter was removed approximately 45 days ago because of dysfunction, and feeding was continued via a nasogastric feeding tube. The silicone nasogastric feeding tube was inserted up to 50 cm. There was no complaint until the last 2 days when fecaloid emesis and fecaloid drainage via the nasogastric feeding tube occurred. -

Collaborative Stage Manual Part II

Appendix C Site-Specific Coding Modules SEER Program Coding and Staging Manual 2004, Revision 1 Table of Contents Site-Specific Coding Modules......................................................................................................C-1 Lip, Upper...........................................................................................................................................C-3 Lip, Lower ........................................................................................................................................C-11 Other Lip...........................................................................................................................................C-19 Base of Tongue, Lingual Tonsil........................................................................................................C-29 Anterior 2/3 of Tongue, Tip, Border, and Tongue, NOS..................................................................C-37 Gum, Upper.......................................................................................................................................C-47 Gum, Lower and Retromolar Area Retromolar Gingiva (Trigone) ..................................................C-55 Gum, NOS ........................................................................................................................................C-63 Floor of Mouth..................................................................................................................................C-71 Hard Palate........................................................................................................................................C-83 -

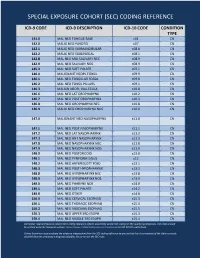

Special Exposure Cohort (Sec) Coding Reference

SPECIAL EXPOSURE COHORT (SEC) CODING REFERENCE ICD-9 CODE ICD-9 DESCRIPTION ICD-10 CODE CONDITION TYPE 141.0 MAL NEO TONGUE BASE c01 CN 142.0 MALIG NEO PAROTID c07 CN 142.1 MALIG NEO SUBMANDIBULAR c08.0 CN 142.2 MALIG NEO SUBLINGUAL c08.1 CN 142.8 MAL NEO MAJ SALIVARY NEC c08.9 CN 142.9 MAL NEO SALIVARY NOS c08.9 CN 145.3 MAL NEO SOFT PALATE c05.1 CN 146.0 MALIGNANT NEOPL TONSIL c09.9 CN 146.1 MAL NEO TONSILLAR FOSSA c09.0 CN 146.2 MAL NEO TONSIL PILLARS c09.1 CN 146.3 MALIGN NEOPL VALLECULA c10.0 CN 146.6 MAL NEO LAT OROPHARYNX c10.2 CN 146.7 MAL NEO POST OROPHARYNX c10.3 CN 146.8 MAL NEO OROPHARYNX NEC c10.8 CN 146.9 MALIG NEO OROPHARYNX NOS c10.9 CN 147.0 MALIGNANT NEO NASOPHARYNX c11.0 CN 147.1 MAL NEO POST NASOPHARYNX c11.1 CN 147.2 MAL NEO LAT NASOPHARYNX c11.2 CN 147.3 MAL NEO ANT NASOPHARYNX c11.3 CN 147.8 MAL NEO NASOPHARYNX NEC c11.8 CN 147.9 MAL NEO NASOPHARYNX NOS c11.9 CN 148.0 MAL NEO POSTCRICOID c13.0 CN 148.1 MAL NEO PYRIFORM SINUS c12 CN 148.2 MAL NEO ARYEPIGLOTT FOLD c13.1 CN 148.3 MAL NEO POST HYPOPHARYNX c13.2 CN 148.8 MAL NEO HYPOPHARYNX NEC c13.8 CN 148.9 MAL NEO HYPOPHARYNX NOS c13.9 CN 149.0 MAL NEO PHARYNX NOS c14.0 CN 149.1 MAL NEO SOFT PALATE c14.2 CN 149.8 MAL NEO OTHER c14.8 CN 150.0 MAL NEO CERVICAL ESOPHAG c15.3 CN 150.1 MAL NEO THORACIC ESOPHAG c15.4 CN 150.2 MAL NEO ABDOMIN ESOPHAG c15.5 CN 150.3 MAL NEO UPPER 3RD ESOPH c15.3 CN 150.4 MAL NEO MIDDLE 3RD ESOPH c15.4 CN Disclaimer: Special Exposure Cohort (SEC) coding reference reflects potentially usable ICD coding for SEC qualifying diagnoses. -

Hospice Appropriate Diagnosis Codes APPENDIX C

APPENDIX C‐DIAGNOSIS CODE CRITERIA Diagnosis code(s) are required when submitting request for hospice services. Certain codes require criteria that must be met before request are approved. The specified codes are identified with an asterisk. Appropriate documentation is required for these codes. This list is not all inclusive. Additional codes may be added upon request with documentation and justification as to why the patient has a prognosis of 6 months or less with this diagnosis. Each code submitted will be considered on a case by case basis. (*) Must provide documentation of treatment failure, cannot be removed surgically, metastatic disease, patient refused surgery and /or treatment. (**) Lymphoma, Leukemia Myeloma and others will meet criteria if there is a failure of treatment. (Must provide documentation) (***) Dementia of any type must have proper documentation of advance dementia with mental minimum score of less than 10. Hospice Appropriate Diagnosis Codes Number Description 042 HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS (HIV) DISEASE 046.3 PROGRESSIVE MULTIFOCAL LEUKOENCEPHALOPATHY 140.4 *MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF LOWER LIP INNER ASPECT 141.0 *MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF BASE OF TONGUE 141.6 *MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF LINGUAL TONSIL 141.9 *MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF TONGUE UNSPECIFIED 142.0 *MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF PAROTID GLAND 144 *MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF FLOOR OF MOUTH 144.0 *MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF ANTERIOR PORTION OF FLOOR OF MOUTH 145 *MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF OTHER AND UNSPECIFIED PARTS 145.2 *MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF HARD PALATE 145.3 *MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF SOFT -

Introduction to Starting Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: Proper Insertion, Complete Observation, and Appropriate Photographing

REVIEW Clin Endosc 2015;48:279-284 http://dx.doi.org/10.5946/ce.2015.48.4.279 Print ISSN 2234-2400 • On-line ISSN 2234-2443 Open Access Introduction to Starting Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: Proper Insertion, Complete Observation, and Appropriate Photographing Kyung Sik Park Department of Internal Medicine, Keimyung University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea Diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is the most basic of endoscopy procedures and is the technique that trainee doctors first learn. Mastering the basics of endoscopy is very important because when this process is imprecise or performed incorrectly, it can severely affect a patient’s health or life. Although there are several guidelines and studies that consider these basics, there are still no standard recommendations for endoscopy in Korea. In this review, basic points, including proper endoscope insertion, precise observation without blind spots, and appropriate photographing, for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy will be discussed. Clin Endosc 2015;48:279-284 Key Words: Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy; Insertion; Observation; Photographing INTRODUCTION rious complications. Once the endoscope is inserted, detailed observation without blind spots is essential for a perfect pro- Due to the recent increased interest in health and the Na- cedure. Quality control in endoscopy procedures has recently tional Cancer Screening Project, the demand for upper and come under heavy discussion;4-7 as such, the storage of endos- lower gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy procedures is rapidly copy data, and photo images in particular, is very important. increasing. Accordingly, many doctors are enrolling in training Specifically, when a patient is transferred for the treatment courses to obtain an endoscopy specialist license. -

Pitfalls in the Staging Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Hypopharynx

Pitfalls in the Staging Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Hypopharynx Amy Y. Chen, MDa, Patricia A. Hudgins, MDb,* KEYWORDS Squamous cell carcinoma Hypopharynx Aryepiglottic fold Larynx KEY POINTS To accurately interpret pretreatment and posttreatment imaging in patients with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), one must understand the complex anatomy of this part of the aerodigestive system. Common patterns of spread must be recognized. Pitfalls in imaging must be understood. This article reviews the epidemiology, anatomy, staging, treatment and pitfalls in imaging of hypo- pharyngeal SCC. INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY statistically the most common malignancy of the hypopharynx. Alcohol potentiates the mutagenic Compared with laryngeal neoplasms, primary effects of tobacco. The biology of HP SCC is inter- hypopharyngeal (HP) tumors, especially those esting, and an area of ongoing study. Mutations in exclusively in the HP subsites, are relatively un- the p53 tumor suppressor gene are more common common, accounting for about 4% of all head in HP SCC than in other head and neck sites.2,3 and neck tumors. Tumors of the hypopharynx Field carcinogenesis, the concept that carcino- are generally advanced stage when detected, gens affect surrounding tissue that has yet to be and have often already extended to the larynx or transformed to tumor, also is common in HP cervical esophagus. Imaging is critical in staging SCC. Thus tumors may be multicentric, spread these advanced primary tumors for guiding treat- submucosally, and be very difficult to stage with ment planning, and because locoregional control imaging or endoscopy alone. At presentation may be difficult to attain, accurate staging is espe- tumors are often at an advanced stage, and the cially critical.