Deadwood – a Genre Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deadlands: Reloaded Core Rulebook

This electronic book is copyright Pinnacle Entertainment Group. Redistribution by print or by file is strictly prohibited. This pdf may be printed for personal use. The Weird West Reloaded Shane Lacy Hensley and BD Flory Savage Worlds by Shane Lacy Hensley Credits & Acknowledgements Additional Material: Simon Lucas, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys Editing: Simon Lucas, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys, Jens Rushing Cover, Layout, and Graphic Design: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Thomas Denmark Typesetting: Simon Lucas Cartography: John Worsley Special Thanks: To Clint Black, Dave Blewer, Kirsty Crabb, Rob “Tex” Elliott, Sean Fish, John Goff, John & Christy Hopler, Aaron Isaac, Jay, Amy, and Hayden Kyle, Piotr Korys, Rob Lusk, Randy Mosiondz, Cindi Rice, Dirk Ringersma, John Frank Rosenblum, Dave Ross, Jens Rushing, Zeke Sparkes, Teller, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Frank Uchmanowicz, and all those who helped us make the original Deadlands a premiere property. Fan Dedication: To Nick Zachariasen, Eric Avedissian, Sean Fish, and all the other Deadlands fans who have kept us honest for the last 10 years. Personal Dedication: To mom, dad, Michelle, Caden, and Ronan. Thank you for all the love and support. You are my world. B.D.’s Dedication: To my parents, for everything. Sorry this took so long. Interior Artwork: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Chris Appel, Tom Baxa, Melissa A. Benson, Theodor Black, Peter Bradley, Brom, Heather Burton, Paul Carrick, Jim Crabtree, Thomas Denmark, Cris Dornaus, Jason Engle, Edward Fetterman, -

Jim Levy, Irish Jewish Gunfighter of the Old West

Jim Levy, Irish Jewish Gunfighter of the Old West By William Rabinowitz It’s been a few quite a few years since Chandler, our grandson, was a little boy. His parents would come down with him every winter, free room and board, and happy Grandparents to baby sit. I doubt they actually came to visit much with the geriatrics but it was a free “vacation”. It is not always sun and surf and pool and hot in Boynton Beach, Fl. Sometimes it is actually cold and rainy here. Today was one of those cold and rainy days. Chandler has long since grown up into a typical American young person more interested in “connecting” in Cancun than vegetating in Boynton Beach anymore. I sat down on the sofa, sweatshirt on, house temperature set to “nursing home” hot, a bowl of popcorn, diet coke and turned on the tube. Speed channel surfing is a game I used to play with Chandler. We would sit in front of the T.V. and flip through the channels as fast as our fingers would move. The object was to try and identify the show in the micro second that the image flashed on the screen. Grandma Sheila sat in her sitting room away from the enervating commotion. She was always busy needle- pointing another treasured wall hanging that will need to be framed and sold someday at an estate sale. With my trusty channel changer at my side, I began flipping through the stations, scanning for something that would be of interest as fast as possible. -

Vol. 40, No. 3, Arches Spring 2013

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Arches University Publications Spring 2013 Vol. 40, No. 3, Arches Spring 2013 University of Puget Sound Follow this and additional works at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/arches Recommended Citation University of Puget Sound, "Vol. 40, No. 3, Arches Spring 2013" (2013). Arches. 17. https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/arches/17 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arches by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNIVERSITY OF PUGET SOUN II. ' HHAS FOR SPRING 2013 Feats in clay - V m V., m mm , ■ #&*> a I PLUS For teachers: A field-trip-in-a-box and Loggers in movieland RISING LIGHT Looking south through the West Woods, on the days when it chooses to show itself we observe the spring sun creeping ever higher, with the firs our colossal measuring sticks. w photojournal r & CHIPPENDELTS Phi Delta Theta pledges were the winners of the Alpha Phi sorority's annual spring-semester philanthropy, Heart Throb. In the days preceding Valentine's Day (Crush Week, as it's called), campus fraternity members are encouraged to buy roses for special someones, with proceeds directed toward Alpha Phi's support of women's cardiac health. The week culminates with a “beauty" pageant testing the men's poise, talent, and knowledge of Alpha Phi. Camera phones ready? And... touch "share." spring 2013 arches photojournal MEETING THE WRITER Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka was this semester's Susan Resneck Pierce lecturer. -

Media Kit an Exclusive Television Event

MEDIA KIT AN EXCLUSIVE TELEVISION EVENT ABOUT SHOWTIME SHOWTIME is the provider of Australia’s premium movie channels: SHOWTIME, SHOWTIME 2 and SHOWTIME Greats. Jointly owned by four A HELL OF A PLACE TO MAKE YOUR FORTUNE MA Medium Level Violence Coarse Language of the world’s leading fi lm studios Sony Pictures, Paramount Pictures, Sex Scenes 20th Century Fox and Universal Studios, as well as global television distributor Liberty Media, the SHOWTIME channels are available on FOXTEL, AUSTAR, Optus, TransAct and Neighbourhood Cable. For further information contact: Catherine Lavelle CLPR M 0413 88 55 95 SERIES PREMIERE 8.30PM WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 3 - continuing weekly E [email protected] showtime.com.au/deadwood In an age of plunder and greed, the richest gold strike in American history draws a throng of restless misfi ts to an outlaw settlement where everything — and everyone — has a price. Welcome to DEADWOOD...a hell of a place to make your fortune. From Executive Producer David Milch (NYPD BLUE) comes DEADWOOD, a new drama series that focuses on the birth of an American frontier town and the ruthless power struggle that exists in its lawless boundaries. Set in the town of DEADWOOD, South Dakota the story begins two weeks after Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn, combining fi ctional and real-life characters and events in an epic tale. Located in the Black Hills Indian Cession, the “town” of DEADWOOD is an illegal settlement, a violent and uncivilized outpost that attracts a colorful array of characters looking to get rich — from outlaws and entrepreneurs to ex-soldiers and racketeers, Chinese laborers, prostitutes, city dudes and gunfi ghters. -

Black Hills, Badlands & Legends of the West

NO RISK DEPOSIT PASSENGER ASSURANCE PLAN Deposit by December 31, 2020 Risk Free until Final Payment Due Date! See inside for details** Lee College Senior Adult Program presents 7 Days June 9, 2021 HIGHLIGHTS • Mount Rushmore • Wall Drug Store • The Journey Museum • Mount Rushmore at Night • Custer State Park • Black Hills Gold Factory • Devil’s Tower Nat’l • Buffalo Jeep Safari • K-Bar S Ranch Dinner Monument • State Game Lodge Dinner • Chuckwagon Supper & • Crazy Horse Memorial • 1880 Train Cowboy Show • Fort Hays • Deadwood • Badlands National Park • Wild Horse Sanctuary Booking Discount - Save $400 per couple!* Contact Information Lee College Senior Adult and Travel Program 511 S. Whiting Street • Baytown, TX 77520 281.425.6311 Booking #145045 (Web Code) [email protected] Black Hills, Badlands & Legends of the West DAY 1: ARRIVE RAPID CITY Day 5: BaDlanDs natIonal PaRk - FoRt hays Today arrive in Rapid City. Enjoy a Welcome Dinner with your Today visit and drive through Badlands National Park, located between traveling companions. the White and Cheyenne Rivers. The area contains spectacular (D) Overnight: Rapid City examples of weathering, erosion, fantastic ridges, cliffs and canyons of variegated color. Later explore the unusual and well-known Wall Day 2: Mount RushMoRe - CRazy hoRse MeMoRIal Drug Store, famous for its “Free Ice Water”. This afternoon visit the This morning visit Mt. Rushmore featuring the awesome sculptures Fort Hays Dances with Wolves Movie Set to see some of the original of Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt and Lincoln. Each face is 60 buildings used in the Oscar winning film. Later at the same location feet high and is carved into the rugged granite mountainside with enjoy a fun filled Chuckwagon Supper & Cowboy Show. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NFS Form 10-900a °MB Approval No. 1024—0018 (Aug. 2002) (Expires Jan. 2005) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number ——— Page ——— SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 05001336 Property Name: Mount Theodore Roosevelt Monument County: Clark State: South Dakota N/A Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. // December 22. 2005 Signature of the Keeper Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: Section 8: Significance. For the Period of Significance, "1919," hereby, replaces "1919-1954" to correspond with the date of construction and the year in which local leader Seth Bullock was directly associated with the construction of the monument. The United States Forest Service was notified of this amendment. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NPS Form 10-900 I jiT I Hull 11 10024-0018 United States Department of the Interior * * —— * /^ National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and ih Jin I ' I'HHu ijmiljiiii in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete'each item by marking "x" in the appropnate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter' N/A for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategones from the instructions. -

Seth Bullock Mt

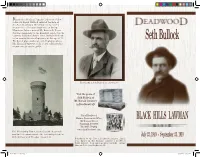

Roosevelt’s death in January 1919 was a blow to his old friend. Bullock enlisted the help of the Society of Black Hills Pioneers to erect a monument to Theodore Roosevelt on Sheep Mountain, later renamed Mt. Roosevelt. It was the first monument to the president erected in the country, dedicated July 4, 1919. Bullock died just a few months later in September at the age of 70. His burial plot resides on a small plateau above Seth Bullock Mt. Moriah Cemetery, with a view of Roosevelt’s monument across the gulch. Photograph of Seth Bullock circa 1890-1900. Visit the grave of Seth Bullock at Mt. Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood, SD City of Deadwood Historic Preservation Office BLACK HILLS LAWMAN 108 Sherman Street Deadwood, SD 57732 Tel.: (605) 578-2082 www.cityofdeadwood.com The Friendship Tower, located on Mt. Roosevelt, was built to commemorate the friendship between Seth Bullock and Theodore Roosevelt. July 23, 1849 - September 23, 1919 Reproduced by the City of Deadwood Archives, March 2013. Images in this brochure courtesy of Deadwood Public Library - Centennial Archives and DHI - Adams Museum Collection, Deadwood, SD EDIT_SEth_01_2013.indd 1 3/15/2013 1:38:57 PM Seth Bullock and Sol Star posing on the 1849 - Seth Bullock - 1919 Redwater Bridge circa 1880s. The quintessential pioneer and settler of the preserve that magnificent land, protecting it he Bullocks were founders of the Round Table American frontier has to be Seth Bullock who, from settlement. His resolution was adopted and T Club, the oldest surviving cultural club in the ironically, was born in Canada. -

The Academy Monitor

THE ACADEMY MONITOR VOLUME 9, ISSUE 3 FROM THE COMMANDANT 3 R Greetings from the great Halls of Learning, D Starfleet Academy! From the Principal’s Office Q I’m not going to list all the awardees from the Academy as they have been sent to several venues, but we had lots. U I enjoyed my very first IC and hope to make it to another one sometime. It won’t be next year, unfortunately. A According to Tammy Willcox, our Scholarship director, she, Bran Stimpson and Linda Olsen have an email R exchange going on regarding some fliers/tri-folds to be used to promote the scholarship program both internally via membership packets and possible recruiting at T colleges and/or conventions and events where STARFLEET members are recruiting people. According to Linda Olson, $174.00 was collected for the Scholarship Fund through new or renewing memberships, bringing a E total donated thru Membership Processing to $403.00 for Promotions the next fiscal year. 2 R Outstanding Students There was a great deal of flak about the Pennies project 3 that R12 started last year prior to this year's IC. What are Cadet News 4 your thoughts on this being some type of official project and promoted through the STARFLEET website? No one Staff/Director/ I/C Awards 5-13 has actually approached her making it official, though Wayne Killough did bring the program up earlier in the Academy Grads 13-21 2 year, and it was brought up at the IC. He mentioned that it would be a good idea for chapters to have a special Academy Degree Program 22 penny jar/piggy bank to put the change in when folks go to 0 their meetings. -

The BG News October 12, 1998

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-12-1998 The BG News October 12, 1998 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 12, 1998" (1998). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6383. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6383 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. MONDAY,The Oct. 12, 1998 A dailyBG independent student News press Volume 85 FORECAST Off-campus student center hours expanded HIGH: 69 LOW: 44 J The hours have been The University's Off-Campus their rooms like those who live but an increase in the funding as here," Limes said. Student Center, OCC, has on campus. However, OCC pro- well. There are many facilities and extended due to an extended its hours. vides this convenience to them. "Off-campus students can services offered at OCC, includ- increase in demand as The new hours are 7:30 a.m. to "I'm glad that it is here," said have a place to call their own, ing a computer lab. Students 10 p.m., Monday through Thurs- Musser. "I use all the services especially during their breaks needing a quiet place to study well as funding. day; 7:30 a.m. -

Justified and the Post 9-11 Western

This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document: Zinder, Paul ORCID: 0000-0002-9578-4009 (2013) Osama bin Laden Ain’t Here: Justified as a 9/11 Western. In: Contemporary Westerns: Film and Television Since 1990. Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Maryland. ISBN 978-0810892569 EPrint URI: http://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/3558 Disclaimer The University of Gloucestershire has obtained warranties from all depositors as to their title in the material deposited and as to their right to deposit such material. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation or warranties of commercial utility, title, or fitness for a particular purpose or any other warranty, express or implied in respect of any material deposited. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation that the use of the materials will not infringe any patent, copyright, trademark or other property or proprietary rights. The University of Gloucestershire accepts no liability for any infringement of intellectual property rights in any material deposited but will remove such material from public view pending investigation in the event of an allegation of any such infringement. PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR TEXT. This is a final draft version of the following published document: Zinder, Paul (2013). Osama bin Laden Ain’t Here: Justified as a 9/11 Western. In: Contemporary Westerns: Film and Television Since 1990. Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Maryland. ISBN 978- 0810892569 Published as a chapter in the book Contemporary Westerns: Film and Television Since 1990 (2013) edited by Andrew Patrick Nelson. All rights reserved. Please contact the publisher for permission to copy, distribute or reprint. -

16 SAG Press Kit 122809

Present A TNT and TBS Special Simulcast Saturday, Jan. 23, 2010 Premiere Times 8 p.m. ET/PT 7 p.m. Central 6 p.m. Mountain (Replay on TNT at 11 pm ET/PT, 10 pm Central, 9 pm Mountain) Satellite and HD viewers should check their local listings for times. TV Rating: TV-PG CONTACTS: Eileen Quast TNT/TBS Los Angeles 310-788-6797 [email protected] Susan Ievoli TNT/TBS New York 212-275-8016 [email protected] Heather Sautter TNT/TBS Atlanta 404-885-0746 [email protected] Rosalind Jarrett Screen Actors Guild Awards® 310-235-1030 [email protected] WEBSITES: http://www.sagawards.org tnt.tv tbs.com America Online Keyword: SAG Awards Table of Contents 16th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® to be Simulcast Live on TNT and TBS ..........................2 Nominations Announcement .................................................................................................................4 Nominations ............................................................................................................................................5 The Actor® Statuette and the Voting Process ....................................................................................23 Screen Actors Guild Awards Nomenclature .......................................................................................23 Betty White to be Honored with SAG’s 46th Life Achievement Award..............................................24 Q & A with Betty White.........................................................................................................................27 -

6/2/2016 Dvdjan03 Page 1

DVDjan03 6/2/2016 MOVIE_NAME WIDE_STDRD STAR1 STAR2 02june2016 BuRay Disney remove group 5198 should add Dig Copies DOC was pbs now most donate Point Break (1991) Bray + dvd + DigHD BluR Patrick Swayze, Keanu Reeves gary busey / lori petty RR for railroad: SURF-separate ; DG (SAVEdv TRAV MUSIC ELVIS (500) day of summer BluRay Joseph Gordon-Levitt zooey deschanel 10 first time on BluRay (Blake Edwards) Dudley Moore / Julie Andrews Bo Derek 10 (blake edwards) 1st on BR BluR dudney moore / julie andrews bo derek / robert webber 10 items of less (netF) 101 one hundred one dalm (toon) Bray dvd dig disney studios diamond edition 101 one hundred one dalmations ws glenn close jeff daniels 12 monkeys ws bruce willis / brad pitt madelaeine stowe / christopher 127 hours BluR james franco 13 going on 30 (sp. Ed.) - bad ws jennifer garner / mark ruffalo judy greer / andy serkis 13 rue madeleine (war classic) james cagney / annabella richard conte / frank latimore 15 minutes robert deniro edward burns 16 Blocks B ray Bruce Willis / David Morse Mos Def 1776 ws william daniels / howard da silv ken howard / donald madden 1941 john belushi 1984 (vhs->dvd) richard burton john hurt 20 feet from stardom DVD + Bluray best doc oscar 2014 20,000 leagues under the sea (disney) kirk douglas / james mason paul anka / peter lorre 2001 a space odyssey ws keir dullea gary lockwood 2001 A Space Odyssey (S Kubrik) top 10 BluR keir dullea / gary lockwood play: Stanley Kubrick / Arthur C 2001:A Space Odyssey Best WarnerBros 50 B 1968 2010 the year make contct wd roy scheider