Why Are Farmers in Manipur Cultivating Poppy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Census Handbook Senapati

DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SENAPATI 1 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SENAPATI MANIPUR SENAPATI DISTRICT 5 0 5 10 D Kilometres er Riv ri a N b o A n r e K T v L i G R u z A d LAII A From e S ! r Dimapur ve ! R i To Chingai ako PUNANAMEI Dzu r 6 e KAYINU v RABUNAMEI 6 TUNGJOY i C R KALINAMEI ! k ! LIYAI KHULLEN o L MAO-MARAM SUB-DIVISION PAOMATA !6 i n TADUBI i rak River 6 R SHAJOUBA a Ba ! R L PUNANAMEIPAOMATA SUB-DIVISION N ! TA DU BI I MARAM CENTRE ! iver R PHUBA KHUMAN 6 ak ar 6 B T r MARAM BAZAR e PURUL ATONGBA v r i R ! e R v i i PURUL k R R a PURUL AKUTPA k d C o o L R ! g n o h k KATOMEI PURUL SUB-DIVISION A I CENTRE T 6 From Tamenglong G 6 TAPHOU NAGA P SENAPATI R 6 6 !MAKHRELUI TAPHOU KUKI 6 To UkhrulS TAPHOU PHYAMEI r e v i T INDIAR r l i e r I v i R r SH I e k v i o S R L g SADAR HILLS WEST i o n NH 2 a h r t I SUB-DIVISION I KANGPOKPI (C T) ! I D BOUNDARY, STATE......................................................... G R SADAR HILLS EAST KANGPOKPI SUB-DIVISION ,, DISTRICT................................................... r r e e D ,, v v i i SUB-DIVISION.......................................... R R l a k h o HEADQUARTERS: DISTRICT......................................... p L SH SAIKUL i P m I a h c I R ,, SUB-DIVISION................................ -

NAGISTA OFFICE of the DISTRICT MAGISTRATE: IMPHAL WEST DISTRICT Tt* PER MIT Imphal, the 20Thjune, 2021 AIC7,M WEST OISTR No

2021 07 20 P-15/B GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR NAGISTA OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT MAGISTRATE: IMPHAL WEST DISTRICT tt* PER MIT Imphal, the 20thJune, 2021 AIC7,M WEST OISTR No. DC (Tw)/1/cON/361/02: Subject to observance of the guidelines for surevilance, contaisment and caution issued by the chairman, National Executive Committee, Government of India ide order no.40 3/2020-DM-1(A) dated 23.03.2021 for effective control of coVID-19 to be implemented w.e.f.01/04/2021 and in relaxation of curfew oders promulgated in CRIL MISC CASE No. 6 of 2021 dated 16th July 2021 of the Court of District Magistrate Imphal West District Shri. Chongtham Gouramani Singh of Singjamei Chongtham Leikai, Imphal West District is hereby permitted to organize "Phiroi" Ceremony of his (Late) wife namely Chongtham Premila Devi , and related gathering on the date ,time and at the place shown below with the following restrictions; Sl. Detail of Place Date Time Concerned No. ceremony From to P.S. Singjamei "Phiroi" Singjamei Chongtham Leikai 8.00.am 1.00.pm|Police 22.07.2021 Station This 'Permie' is issued with the following restrictions: 1. All Covid appropriate behaviors shall be strictly followed. 2. Feasting is not allowed and size of family gathering for social ,religious, customary ceremonies should be restricted to 20(Twenty) or less person strictly. 3. Wearing face mask is compulsory. 4. No elaborate arrangements should be made which would amount to violation of directives/ instruction/ advisories issued by the Government of India /State Government/District Administration. 5. -

District Report SENAPATI

Baseline Survey of Minority Concentrated Districts District Report SENAPATI Study Commissioned by Ministry of Minority Affairs Government of India Study Conducted by Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development: Guwahati VIP Road, Upper Hengerabari, Guwahati 781036 1 ommissioned by the Ministry of Minority CAffairs, this Baseline Survey was planned for 90 minority concentrated districts (MCDs) identified by the Government of India across the country, and the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi coordinates the entire survey. Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development, Guwahati has been assigned to carry out the Survey for four states of the Northeast, namely Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Manipur. This report contains the results of the survey for Senapati district of Manipur. The help and support received at various stages from the villagers, government officials and all other individuals are most gratefully acknowledged. ■ Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development is an autonomous research institute of the ICSSR, New delhi and Government of Assam. 2 CONTENTS BACKGROUND....................................................................................................................................8 METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................................................9 TOOLS USED ......................................................................................................................................10 -

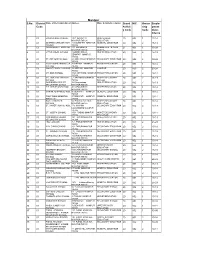

Manipur S.No

Manipur S.No. District Name of the Establishment Address Major Activity Description Broad NIC Owner Emplo Code Activit ship yment y Code Code Class Interva l 101OKLONG HIGH SCHOOL 120/1 SENAPATI HIGH SCHOOL 20 852 1 10-14 MANIPUR 795104 EDUCATION 201BETHANY ENGLISH HIGH 149 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 SCHOOL 795104 301GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL 125 MAKHRALUI HUMAN HEALTH CARE 21 861 1 30-99 MANIPUR 795104 CENTRE 401LITTLE ANGEL SCHOOL 132 MAKHRELUI, HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 SENAPATI MANIPUR 795106 501ST. ANTHONY SCHOOL 28 MAKHRELUI MANIPUR SECONDARY EDUCATION 20 852 2 30-99 795106 601TUSII NGAINI KHUMAI UJB 30 MEITHAI MANIPUR PRIMARY EDUCATION 20 851 1 10-14 SCHOOL 795106 701MOUNT PISGAH COLLEGE 14 MEITHAI MANIPUR COLLEGE 20 853 2 20-24 795106 801MT. ZION SCHOOL 47(2) KATHIKHO MANIPUR PRIMARY EDUCATION 20 851 2 10-14 795106 901MT. ZION ENGLISH HIGH 52 KATHIKHO MANIPUR HIGHER SECONDARY 20 852 2 15-19 SCHOOL 795106 SCHOOL 10 01 DON BOSCO HIGHER 38 Chingmeirong HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 7 15-19 SECONDARY SCHOOL MANIPUR 795105 11 01 P.P. CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 40 LAIROUCHING HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 1 10-14 MANIPUR 795105 12 01 MARAM ASHRAM SCHOOL 86 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 852 1 10-14 795105 13 01 RANGTAIBA MEMORIAL 97 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 853 1 10-14 INSTITUTE 795105 14 01 SAINT VINCENT'S 94 PUNGDUNGLUNG HIGHER SECONDARY 20 852 2 10-14 SCHOOL MANIPUR 795105 EDUCATION 15 01 ST. XAVIER HIGH SCHOOL 179 MAKHAN SECONDARY EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 LOVADZINHO MANIPUR 795105 16 01 ST. -

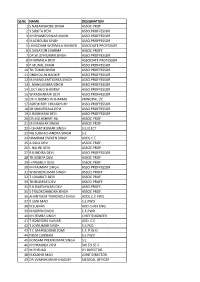

Slno Name Designation 1 S.Nabakishore Singh Assoc.Prof 2 Y.Sobita Devi Asso.Proffessor 3 Kh.Bhumeshwar Singh

SLNO NAME DESIGNATION 1 S.NABAKISHORE SINGH ASSOC.PROF 2 Y.SOBITA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 3 KH.BHUMESHWAR SINGH. ASSO.PROFFESSOR 4 N.ACHOUBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 5 LUNGCHIM WORMILA HUNGYO ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 6 K.SANATON SHARMA ASSOC.PROFF 7 DR.W.JOYKUMAR SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 8 N.NIRMALA DEVI ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 9 P.MUNAL SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 10 TH.TOMBI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 11 ONKHOLUN HAOKIP ASSO.PROFFESSOR 12 M.MANGLEMTOMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 13 L.MANGLEMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 14 LUCY JAJO SHIMRAY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 15 W.RADHARANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 16 DR.H.IBOMCHA SHARMA PRINCIPAL I/C 17 ASHOK ROY CHOUDHURY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 18 SH.SHANTIBALA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 19 K.RASHMANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 20 DR.MD.ASHRAF ALI ASSOC.PROF 21 M.MANIHAR SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 22 H.SHANTIKUMAR SINGH S.E,ELECT. 23 NG SUBHACHANDRA SINGH S.E. 24 NAMBAM DWIJEN SINGH ADDL.C.E. 25 A.SILLA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 26 L.NALINI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 27 R.K.INDIRA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 28 TH.SOBITA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 29 H.PREMILA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 30 KH.RAJMANI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 31 W.BINODKUMAR SINGH ASSCO.PROFF 32 T.LOKABATI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 33 TH.BINAPATI DEVI ASSCO.PROFF. 34 R.K.RAJESHWARI DEVI ASSO.PROFF., 35 S.TRILOKCHANDRA SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 36 AHANTHEM TOMCHOU SINGH ADDL.C.E.PWD 37 K.SANI MAO S.E.PWD 38 N.SUBHAS ADD.CHIEF ENG. 39 N.NOREN SINGH C.E,PWD 40 KH.TEMBA SINGH CHIEF ENGINEER 41 T.ROBINDRA KUMAR ADD. C.E. -

District Courts Presiding Officers

THE HIGH COURT OF MANIPUR List of Presiding Officers and Court Complexes SL.No COURT/TRIBUNAL PRESIDING OFFICER COURT COMPLEX . 1 District & Sessions Judge, Imphal Smt. R.K.Memcha Devi East 2 CJM Imphal West Shri Y. Somorjit Singh Cheirap C.C., 3 District & Sessions Judge, Imphal Shri A. Guneshwar Sharma Uripok, West Imphal 4 Judge, Special Court, NDPS Shri Lamkhanpau Tonsing (FTC),Manipur 5 Member Secretary, Manipur State Shri Ojesh Mutum Legal Services Authority 6 Family Court, Manipur Smt Binny Ngangom 7 ND&PS, Manipur Shri Lamkhanpau Tonsing(i/c) 8 Addl. District & Session Court(FTC), Km. Reena Serto Manipur East 9 Addl. District & Session Court(FTC), Shri Letkho Kipgen Manipur West 10 Civil Judges(Sr.Div), Imphal East Shri K.Nirojit 11 Civil Judges(Sr.Div), Imphal West Shri N.Sonykumar 12 CJM Imphal East Smt N. Lanleima 13 Civil Judge (Sr,Divn.)/CJM, Shri K.Nirojit (i/c) Tamenglong Lamphel C.C 14 Secretary, District Legal Services Shri Y. Somorjit Singh(i/c) Authority, Imphal West 15 Secretary, District Legal Services Smt N. Lanleima(i/c) Authority, Imphal East 16 Civil Judge (Jr, Divn.)/JMFC, Smt. Laishram Rina Devi Imphal West-I 17 Civil Judges(Jr.Div)/JMFC, Imphal Miss Heeralata West-II Moirangthem 18 Add.Session Judge (FTC), CAW, Km. Reena Serto (i/c) Manipur 19 Family Court, Imphal East Smt Binny Ngangom (i/c) 20 Addl. Member Secy. MASLSA Mr S. Sadananda Singh (i/c) 21 Civil Judge (Jr. Divn.)/JMFC, Imphal Km.Kimneingah Kipgen East 22 Deputy Member Secretary MASLSA Mr S. Sadananda Singh 23 District & Session Court, Thoubal Smt. -

Kangpokpi District in the State of Manipur Is a Newly Created District by the Government of Manipur Vide Govt

KANGPOKPI DISTRICT PROFILE: Kangpokpi District in the state of Manipur is a newly created district by the Government of Manipur vide Govt. notifiation No.16/20/2016-R dated 08-12-2016 and subsequent corrigendum dated 14-12-2016 of Secretariat; Revenue Department, Govt. of Manipur. It was inaugurated by Hon'ble Chief Minister, Manipur on the 15th December, 2016. It is inhabited by multi- ethnic groups with inherent socio-economic and cultural backgrounds, mainly, the indegenous Kukis, Nagas, Nepalis and meiteis. The administration of Kangpokpi District is headed by the Deputy Commissioner, Kangpokpi. Kangpokpi District Headquarter is situated at Kangpokpi Town which is at an altitude of 992 metres from Mean Sea Level and at a distance of about 45 kms from the state capital, Imphal. Kangpokpi District comprises of mainly Nine (9) sub-divisions viz, Kangpokpi, Saitu- Gamphazol, Saikul, Kangchup-Geljang, Bungte-Chiru, Island, Champhai and Lhungtin. These nine (9) Sub-Divisions boundaries form the boundary extent of Kangpokpi District. The area of the district is approximately 1698 Sq.Kms and comprises of 534 census villages and some hamlets. The population of the whole of Kangpokpi District as per Census 2011 is 1,93,744 comprising of 98,908 males and 94,836 females. Kangpokpi District has an autonomous district council, by name, Sadar Hills Autonomous District Council headed by its Chairman with 24 elected MDCs and 2 nominated MDCs Population Census 1. 3.35 Lakhs (out of which 96% of population live in Rural Area, 2. 4% live in urban area (7th most populous district) 3. 20% General, 80% ST 4. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Senapati District

1 Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Senapati District MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India), Takyelpat Industrial Estate, Imphal - 795001 Phone: 0385-2416220 e-mail :[email protected] Web :www.msmediimphal.gov.in 2 MAP OF SENAPATI DISTRICT. 3 P R E F A CE The present Report attempts to highlight the followings: - State of the economy of the District - Resource Base of the District - Infrastructure conducive for industrial development - A study of existing industries; and - Identification of industrial potential in the District. - cluster development - Skill development training needs and other incentive/schemes etc. Manipur as a whole is a hilly district and basic infrastructures for industrial growth is yet to be developed..An effort has been made to incorporate the aims, objectives and guidelines of the DC(MSME) as revised & updated from time to time. Mention may be made of the difficulties faced in gathering relevant information about the District as the administrative delineation is in nascent stages and dis-aggregated data for the District are not available from the concerned departments yet. as expected and most of potentials of the district is obtained from various persons who thoroughly knows about the district. I would like to place on record my appreciation to all officials and persons for the various inputs received from them which makes possible of this profile. And hanks are also due to the concerned District and State authorities for providing the necessary information. I look forward to received continued support from all concern and committed to bring out a better & meaningful profile in near future. -

WEST DISTRIC/S 1Rale

2021| 07 061 M-276/B GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR STRC,MAC OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT MAGISTRATE: IMPHAL WEST DISTRIC/S 1Rale *** PER MII Imphal. the 06th July, 2021 WEST RI No. DC (Iw)/1/CON/361/02: Subject to observance of the guidelines for surevilance, contanment of India vide order no.40- and caution issued by the chairman, National Executive Committee, Government 3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 23.03.2021 for effective control of COVID-19 to be implemented w.e.f.01/04/2021 March with orders of even dated and in pursuance of order No. H-1601/6/2020-HD-HD dated 31st 2021,read Government of Shri. Ibochou 16th and 18th April, 2021 of the Home Department, Manipur, Khuraijam Tera Lukram West District is permitted to organize Singh of Sagolband Leirak, Imphal hereby son with Ngairangbam Sophia D/o "Marriage Ceremony" of his namely Sunil Khuraijam time at Ngairangbam Shashi Singh of Uripok Sinam Leikai, and related gathering on the date, the place shown below with the following restrictions; Concerned SI. Detail of Place Date Time to ceremony From P.S. No. 9:00 a.mn. 5:00 p.m.| Lamphel Heijingpot Sagolband Tera 15.07.2021 Police Marriage Lukram Leirak 16.07.2021 9:00 a.m. 5:00 p.m. Station 2. Ceremony" This 'Permit'is issued with the following restrictions: function should not fall within notified containment area. 1. The Families and location of be followed. 2. All Covid appropriate behaviors shall strictly ceremonies should be restricted to 20(Twenty) or 3. Size of family gathering for social, religious, customary less person strictly. -

Sl.No Name of Block Name of CSC Name of Location

DISTRICT :- IMPHAL-WEST No. of Active CSCs :-61 IMPHAL WEST I BLOCK Sl.no Name of Block Name of CSC Name of Location Name of VLE 1 Imphal West -I CSC Lamphel Supaer market Thangmeiband Hijam Dewan Leikai , Imphal Chungkham Maheta Devi West District, Lamphel Seb-Diveision 2 Imphal West -I CSC Sagolband Tera ND Road Sagolband Ingudam Leirak, Sagolband Tera NC Sarangthem Bimola Devi road, , Imphal West -I Block, Imphal West District, PS lamphel, PO Imphal , Pin No. 795001 3 Imphal West-I CSC IM ward no. 27 Iroisemba, Imphal West , IMC Ward No. 27, Rajendro Akoijam Imphal West District 4 Imphal West-I CSC imphal Municipal Council Shop Address: keishampat thiyam leikai , Imphal Oinam Deepak Singh West-I block, PO/PS Imphal, word no -9 , 795001 Home: sega road konjeng hazario leikai , airport road (Imphal West M aipur PO/PS Imphal 5 imphal West-I CSC Sagolband salam leikai Sagolband salam leikai,imphal municipal Council Hidangmayum Rabindra Sharma Ward no. 8 Imphal West -I Block, PO Imphal PS Lamphel 6 Imphal West -I CSC G-net Cyber Cafe, Thangal Nagamapal Soram Leirak, Near CRTTI, Imphal Thangjam Diamond Singh Bazar, Khoyathong Road West District, PO/ PS Imphal H/Q Manipur - 795004, Shop add: G-net Cyber Cafe, Thangal Bazar, Khoyathong Road, 795001 7 Imphal West -I CSC Sangaiprou Near ISKCON Sangaiprou Near ISKCON Temple, Imphal West -I Langpoklakpam Meena Devi Templae block, Imphal West Disrict, Manipur 795001 8 Imphal West -I CSC Green Foundation, Kwakeithal Awang Thiyam leikai, Ward no -10, Thiyam Ronel Singh Kwakeithal Awang Thiyam leikai Imphal West -I block, PO/PS Imphal , Manipur, Pin 795001 9 imphal West-I CSC Sekmai makha leikai Sekmai makha leikai, semmai Nager panchayet, Khundrakpam Malemnganba Imphal West District, PO/PS sekmai , pin 795136 10 Imphal West-I CSC Near DM collage western Thangmeibnd Maisanam leikai, near DM colledge Rajkumar Amarjit Singh gate western gate, PO/PS lamphel, Municipal Council Ward no. -

For Newly Created Kangpokpi District, Manipur State

VISION DOCUMENT (2017-2022) FOR NEWLY CREATED KANGPOKPI DISTRICT, MANIPUR STATE:- Kangpokpi District has recently been created along with 6(six) other Districts out of erstwhile Senapati District thereby increasing the total numbers of Districts from 9(nine) to 16 (Sixteen) in the State vide Govt. of Manipur's Order dated 08-12-2016 and subsequent Corrigendum dated 14-12-2016. The new District comprises of 9 (nine) Sub- Divisions viz. Kangpokpi, Champhai, Tujang Waichong, Saikul, Island, Lhungtin, Saitu Gamphazol, Bungte Chiru and Kangchup Geljang. Immediately, after the creation of the District on 08-12-2017, the newly posted Deputy Commissioner/Kangpokpi and Superintendent of Police/Kangpokpi District has taken their charges on 9th December, 2016. This newly created Kangpokpi District has already been inaugurated by Shri O. Ibobi Singh, the then Hon'ble Chief Minister, Manipur on 15th December, 2016. 2. Out of these 9 Sub-Divisions, 3(three) Sub-Divisions viz Kangpokpi, Saikul & Saitu Gamphazol are fully functional as on date and the remaining Sub-Divisions are partly functional/yet to be functional. As on date, another 4 more MCS Officers have been posted as SDOs/BDOs in 4 Sub-Divisions – Kangchup Geljang, Bungte Chiru, Island and Lungtin. Some few skeleton Staff of Revenue as well as Development have been posted. No SDOs are posted at Champhai & T. Waichong Sub-Divisions till date. DDOs as well as HOOs powers have already been delegated to all SDOs/BDOs. This newly created Kangpokpi District has an area of about 1,698 sq. Km. and the district is inhabited by heterogeneous ethnic groups with inherent socio-economic and cultural background, including the indigenous Kukis, the Nagas, the Nepalis and the Meiteis/Meeteis. -

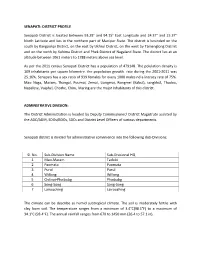

Senapati: District Profile

SENAPATI: DISTRICT PROFILE Senapati District is located between 93.29° and 94.15° East Longitude and 24.37° and 25.37° North Latitude and lies in the northern part of Manipur State. The district is bounded on the south by Kangpokpi District, on the east by Ukhrul District, on the west by Tamenglong District and on the north by Kohima District and Phek District of Nagaland State. The district lies at an altitude between 1061 meters to 1788 meters above sea level. As per the 2011 census Senapati District has a population of 479148. The polulation density is 109 inhabitants per square kilometre. the population growth rate during the 2001-2011 was 25.16%. Senapati has a sex ratio of 939 females for every 1000 males nd a literacy rate of 75%. Mao Naga, Maram, Thangal, Poumai, Zemai, Liangmai, Rongmei (Kabui), tangkhul, Thadou, Napalese, Vaiphei, Chothe, Chiru, Maring are the major inhabitants of this district. ADMINSTRATIVE DIVISION: The District Administration is headed by Deputy Commissioner/ District Magistrate assisted by the ADC/ADM, SDOs/BDOs, SDCs and District Level Officers of various departments. Senapati district is divided for administrative convinience into the following dub-Divisions: Sl. No. Sub-Division Name Sub-Divisional HQ 1 Mao-Maram Tadubi 2 Paomata Paomata 3 Purul Purul 4 Willong Willong 5 Chilivai-Phaibubg Phaibubg 6 Song-Song Song-Song 7 Lairouching Lairouching The climate can be describe as humid subtropical climate. The soil is moderately fertile with clay loam soil. The temperature ranges from a minimum of 3.4°C(38.1°F) to a maximum of 34.1°C (93.4°F).