Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution List

Revised DEIS/EIR Truckee River Operating Agreement DISTRIBUTION LIST CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATIONS Nevada Senators John Ensign Harry Reid Representatives Shelly Berkley (District 1) James A. Gibbons (District 2) Jon C. Porter (District 3) California Senators Barbara Boxer Dianne Feinstein Representatives John T. Doolittle (District 4) Robert T. Matsui (District 5) Doug Ose (District 3) NEVADA STATE SENATE Mark E. Amodei, Carson City Bernice Mathews, Reno Mike McGinness, Fallon William J. Raggio, Reno Randolph Townsend, Reno Maurice E. Washington, Sparks NEVADA STATE ASSEMBLY Bernie Anderson, Sparks Sharron Angle, Reno Jason Geddes, Reno Dawn Gibbons, Reno Tom Grady,Yerington Ron Knecht, Carson City Distribution List-1 Revised DEIS/EIR Truckee River Operating Agreement CALIFORNIA STATE SENATE Samuel Aanestad (District 4) Michael Machado (District 5) Thomas "Rico" Oller (District 1) Deborah Ortiz (District 6) CALIFORNIA STATE ASSEMBLY David Cox (District 5) Tim Leslie (District 4) Darrell Steinberg (District 9) FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AGENCIES Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Washington, DC Army Corps of Engineers, Reno, NV Army Corps of Engineers, Washington, DC Army Corps of Engineers, Real Estate Division, Sacramento, CA Army Corps of Engineers, Planning Division, Sacramento, CA Bureau of Indian Affairs, Office of Trust and Economic Development, Washington, DC Bureau of Indian Affairs, Washington, DC Bureau of Indian Affairs, Western Regional Office, Phoenix, AZ Bureau of Land Management, Carson City District Office, Carson City, NV -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Amendment of Part 74 of the Commission’s ) MB Docket No. 18-119 Rules Regarding FM Translator Interference ) ) COMMENTS OF NEW YORK PUBLIC RADIO New York Public Radio (“NYPR”) is pleased to submit these Comments in response to the above-referenced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (the “NPRM”).1 NYPR is the licensee of WNYC-FM, New York, NY, a news and talk public radio station dedicated to award-winning enterprise journalism, community engagement around critical issues, and courageous conversations convened via local and national programs. In addition, NYPR is the licensee of WNYC(AM), New York, NY and WQXR-FM, Newark, NJ. Like its FM sister station, WNYC(AM) is a news and talk public radio station, while WQXR-FM is New York City’s only all-classical music station. NYPR is also home to WNYC Studios, the premier producer of critically-acclaimed on-demand and broadcast audio content for national audiences, and The Jerome L. Greene Performance Space, the street-level broadcast studio and performance venue of WNYC-FM and WQXR-FM. In addition, NYPR owns and operates New Jersey Public Radio, an award-winning news service that provides journalism and public affairs coverage about the Garden State, and New Jersey Public Radio’s four affiliated FM stations: WNJT-FM, Trenton, NJ; WNJO(FM), Toms River, NJ; WNJP(FM), Sussex, NJ; and WNJY(FM), Netcong, NJ. NYPR reaches a passionate community of almost 26 million people monthly on-air, online, and in person. 1 In re Amendment of Part 74 of the Commission’s Rules Regarding FM Translator Interference, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, MB Docket No. -

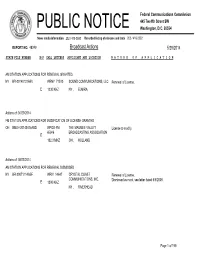

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

Media Ownership Rules

05-Sadler.qxd 2/3/2005 12:47 PM Page 101 5 MEDIA OWNERSHIP RULES It is the purpose of this Act, among other things, to maintain control of the United States over all the channels of interstate and foreign radio transmission, and to provide for the use of such channels, but not the ownership thereof, by persons for limited periods of time, under licenses granted by Federal author- ity, and no such license shall be construed to create any right, beyond the terms, conditions, and periods of the license. —Section 301, Communications Act of 1934 he Communications Act of 1934 reestablished the point that the public airwaves were “scarce.” They were considered a limited and precious resource and T therefore would be subject to government rules and regulations. As the Supreme Court would state in 1943,“The radio spectrum simply is not large enough to accommodate everybody. There is a fixed natural limitation upon the number of stations that can operate without interfering with one another.”1 In reality, the airwaves are infinite, but the govern- ment has made a limited number of positions available for use. In the 1930s, the broadcast industry grew steadily, and the FCC had to grapple with the issue of broadcast station ownership. The FCC felt that a diversity of viewpoints on the airwaves served the public interest and was best achieved through diversity in station ownership. Therefore, to prevent individuals or companies from controlling too many broadcast stations in one area or across the country, the FCC eventually instituted ownership rules. These rules limit how many broadcast stations a person can own in a single market or nationwide. -

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

2015 Artown Team

2015 Artown Team Chris Fleiner, Chair Terry McQuattie, Past Chair Reno Lumber U.S Bank District Manager Board Chris Christiansen, Vice Chair Oliver X Grand Sierra Resort Reno Tahoe Tonight Magazine Members Miranda Roberts, Secretary Naomi Duerr The Good Life Reno City Council Rachael Thomsen, Treasurer Jessica Schneider Eide Bailly LLP Junkee Clothing Exchange Staff Outsourced Services Beth Macmillan Kristen Timmerman Executive Director Discover The Arts Jennifer Mannix Tim Kuhlman Director of Marketing Fluke Advertising Design Kiki Cladianos Kate York CPA Festival Assistant Accounting Services Festival Interns Beth Cooney Shane Vetter Sponsorship Dana Nelson David Lan Kollin Perry Focusing Computing Stan Can Design Photographers Poster Layout Peter Walker Chris Holloman Susan Boskoff and Presenters Mission Statement To strengthen Reno’s arts industry, foster its civic identity and enhance its national image, thereby creating a climate for the cultural and economic rebirth of our region. Table of Contents Commissioned Artists 1 Executive Summary 3 The City of Reno, Artown’s Major Funder 11 Festival Sponsors 12 Event, Commission and Champion Sponsors 13 Media Sponsors 15 Artown Exposure 19 Other Revenue Streams 20 2015 Volunteers 21 Presenters 22 Audience Comments 24 Friends of Artown 28 Photographers: Chris Holloman, Peter Walker, Susan Boskoff and Artown Presenters Artown Commissioned Artists Anniversary Poster: The annual Artown poster defines and celebrates the year’s festivities and is a highly coveted project. To celebrate the 20th year and the July 2015 festival, Artown commissioned locally grown artist, Franz Szony, to create this signature piece. With his passion for the arts and his vast experience with each Artown Festival, Franz created a clever and unique story to tie into this year’s festival. -

An Exploration of Recording and the Music Business

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Honors Projects Honors College Spring 4-30-2017 An Exploration of Recording and the Music Business Erika Nalow [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Arts Management Commons, Audio Arts and Acoustics Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Nalow, Erika, "An Exploration of Recording and the Music Business" (2017). Honors Projects. 258. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects/258 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Erika Nalow HNRS 4990 Honors Project Conclusion An Exploration of Recording and the Music Business The following questions were initially proposed during the planning of my Honors Project. I have chosen to organize the final project results around these questions and how they were specifically answered through conducting my creative project. “Can an independent artist record, mix, produce, promote, and distribute their own original work successfully?” o To answer this part of the research thoroughly, I will give a detailed recitation of the planning and execution of this project. This project began with me writing an original song entitled “Upside Down.” After composing it, I went to my project advisor, Mark Bunce, and reserved a day in the Kuhlin Center recording studio on BGSU’s campus to record the song. I then arranged additional music for the song- writing parts for trombone, trumpet, alto saxophone, acoustic guitar, electric guitar, bass, drums, piano, and vocals. -

Plan Ahead Nevada Brought to You by the State of Nevada, Department of Public Safety, Division of Emergency Management

TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW AND PREPAREDNESS LISTS INTRODUCTION LETTER PG. 3 STEP BY STEP PREPAREDNESS LIST PG. 4 FAMILY PREPAREDNESS PG. 6 At WORK PREPAREDNESS PG. 8 EVACUATION & SHELTER TIPS PG. 10 EMERGENCY COMMUNICATIONS PG. 11 BASIC EMERGENCY SUPPLY KIT PG. 12 TYPES OF DISASTER TO PREPARE FOR WILDLAND FIRE PG. 13 EARTHQUAKE PG. 14 FLOOD PG. 15 EXTREME WEATHER PG. 16 FLU PANDAMIC PG. 17 TERRORISM PG. 18 HAZARD MITIGATION WHAT IS HAZARD MITIGATION? PG. 19 MITIGATION FOR WILDFIRE PG. 20 MITIGATION FOR EARTHQUAKE PG. 20 MITIGATION FOR FLOODS PG. 21 YOUR COMMUNITY, YOUR PREPAREDNESS YOUR EVACUATION PLAN PG. 22 YOUR EMERGENCY CONTACTS PG. 23 MEDIA COMMUNICATIONS PG 24 YOUR COUNTY EVACUATION PLAN PG. 26 Plan Ahead Nevada Brought to you by The State of Nevada, Department of Public Safety, Division of Emergency Management. Content provided in part by FEMA. Funding Granted By U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2 STAT E DIVISION OF EM E RG E NCY MANAG E M E NT A MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF “Proudly serving the citizens of the State of Nevada, in emergency NEVADA preparedness response and recovery.” EMERGENCY MITIGATION GUIDE FRANK SIRACU S A , CHIE F This brochure, funded through the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, is the result of statewide participation from public safety officials and first responders in addressing “Preparedness Response and Recovery” emergency mitigation. It is developed to provide helpful tips and techniques in prepar- ing your family, friends and pets for emergency conditions. Hazard Mitigation is the cornerstone of the Four Phase of Emergency Management. The term “Hazard Mitigation” describes actions that can help reduce or eliminate long-term risks caused by natural hazards, or disasters, such as wildfires, earthquakes, thunderstorms, floods and tornadoes . -

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1)

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1) Full Full Full Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation 2 Los Angeles, CA KTLA The CW 57 Mobile, AL WKRG CBS 111 Springfield, MA WWLP NBC 3 Chicago, IL WGN Independent WFNA The CW 112 Lansing, MI WLAJ ABC 4 Philadelphia, PA WPHL MNTV 59 Albany, NY WTEN ABC WLNS CBS 5 Dallas, TX KDAF The CW WXXA FOX 113 Sioux Falls, SD KELO CBS 6 San Francisco, CA KRON MNTV 60 Wilkes Barre, PA WBRE NBC KDLO CBS 7 DC/Hagerstown, WDVM(2) Independent WYOU CBS KPLO CBS MD WDCW The CW 61 Knoxville, TN WATE ABC 114 Tyler-Longview, TX KETK NBC 8 Houston, TX KIAH The CW 62 Little Rock, AR KARK NBC KFXK FOX 12 Tampa, FL WFLA NBC KARZ MNTV 115 Youngstown, OH WYTV ABC WTTA MNTV KLRT FOX WKBN CBS 13 Seattle, WA KCPQ(3) FOX KASN The CW 120 Peoria, IL WMBD CBS KZJO MNTV 63 Dayton, OH WDTN NBC WYZZ FOX 17 Denver, CO KDVR FOX WBDT The CW 123 Lafayette, LA KLFY CBS KWGN The CW 66 Honolulu, HI KHON FOX 125 Bakersfield, CA KGET NBC KFCT FOX KHAW FOX 129 La Crosse, WI WLAX FOX 19 Cleveland, OH WJW FOX KAII FOX WEUX FOX 20 Sacramento, CA KTXL FOX KGMD MNTV 130 Columbus, GA WRBL CBS 22 Portland, OR KOIN CBS KGMV MNTV 132 Amarillo, TX KAMR NBC KRCW The CW KHII MNTV KCIT FOX 23 St. Louis, MO KPLR The CW 67 Green Bay, WI WFRV CBS 138 Rockford, IL WQRF FOX KTVI FOX 68 Des Moines, IA WHO NBC WTVO ABC 25 Indianapolis, IN WTTV CBS 69 Roanoke, VA WFXR FOX 140 Monroe, AR KARD FOX WTTK CBS WWCW The CW WXIN FOX KTVE NBC 72 Wichita, KS -

Won't Make Hundreds of Millions of Dollars While Their Employees Are Below the Poverty Line

won't make hundreds of millions of dollars while their employees are below the poverty line. Hillary said "We are going to take things away from you for the common good." Goddess bless her. We need stations like WTPG to show the masses what we liberals Dlan to do to helD this countw. Jeff Coryell 44118 The progressive community in Columbus is vibrant and growing. More and more Ohioans are seeing through the empty right wing spin and coming around to the common-sense progressive agenda. They need a radio station that respects their point of view! ~oan Fluharty 43068 Sara Richman 01940 Progressive Talk Radio sserves an imponant for the public to hear another side of the issues. Talk radio is "lopsidedly" one sided and as we know, this is extremely dangerous in a democracy. Boston lost their Progressive Talk Radio and I feel as if I lost a friend. Out of habit, when I turn to the station in the car or in the kitchen, I get annoying rumba music. I wish a petition could be started to have another Boston station broadcast Progressive Talk. I khank you, Sara Richman Karl lKav 143232 IProqressive radio is imDonant in Central Ohio because someone has to tell They are more than willing to patronize any advenisers to the channel. arilyn eerman Franken and Schultz have reg Iavis 1230 since it started in Columbus in September 2004. On average, we e listened to AM1230 for eight to ten hours a day (my wife listens to it a 1230, as have many of our friends and acquaintances. -

Uvfuv 90.7 F M New York

FORDHAM UNIVERSITY BRONX, NEW YORK 10458 (212) 933-2233 EXT. 243-244 uvfuv 90.7 f m new york May 7th, 1973 160 West 73d St. New York City 10023 Miss Jane Becker Publicity Manager ALFRED A. KNOPF INC. 201 East 50th St. New York City Dear Miss Becker: I note that the publication date for Artur Rubinstein's new book is near. I thought I would send you this £ote in regard to my broadcasts^ in the even something might be worked out. As the enclosed indicates—I am a concert pianist, having been a scholarship student at the Juilliard with the late Olga Samaroff- Stokowsky, and also having spent a summer with Josef Hofmann. My radio show----- "BERNARD GABRIEL VIEWS THE MUSIC SCENE" has been on the air nearly 7 years now-.....- and I interview such musical figures as: YEHUDI MENUHIN, SIR RUDOLF BING, ERICA MORINI, LILI KRAUS, LEON BARZIN, THOMAS SCHERMAN, EARL WILD, WILLIAM MASSELOS, JOHN STEINWAY etc. etc. I mention the above-------because, I imagine Artur Rubinstein might be tempted to do an interview, since I am a professional musician —and might not just do the usual generalized type of chat with him. My broadcasts are heard by a great many radio stations coast to coast-------via "NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO", and are heard independently over WFUV in NYC every Monday night---------- 9-9:30PM. I should greatly like to talk with Mr. Rubinstein-------but in any everiTwould like to review the book.(l di a great many book reviews on the show, and talk with a variety of authors.) Possibly you would show Mr. -

FY 2016 and FY 2018

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Appropriation Request and Justification FY2016 and FY2018 Submitted to the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee and the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee February 2, 2015 This document with links to relevant public broadcasting sites is available on our Web site at: www.cpb.org Table of Contents Financial Summary …………………………..........................................................1 Narrative Summary…………………………………………………………………2 Section I – CPB Fiscal Year 2018 Request .....……………………...……………. 4 Section II – Interconnection Fiscal Year 2016 Request.………...…...…..…..… . 24 Section III – CPB Fiscal Year 2016 Request for Ready To Learn ……...…...…..39 FY 2016 Proposed Appropriations Language……………………….. 42 Appendix A – Inspector General Budget………………………..……..…………43 Appendix B – CPB Appropriations History …………………...………………....44 Appendix C – Formula for Allocating CPB’s Federal Appropriation………….....46 Appendix D – CPB Support for Rural Stations …………………………………. 47 Appendix E – Legislative History of CPB’s Advance Appropriation ………..…. 49 Appendix F – Public Broadcasting’s Interconnection Funding History ….…..…. 51 Appendix G – Ready to Learn Research and Evaluation Studies ……………….. 53 Appendix H – Excerpt from the Report on Alternative Sources of Funding for Public Broadcasting Stations ……………………………………………….…… 58 Appendix I – State Profiles…...………………………………………….….…… 87 Appendix J – The President’s FY 2016 Budget Request...…...…………………131 0 FINANCIAL SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING’S (CPB) BUDGET REQUESTS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016/2018 FY 2018 CPB Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting requests a $445 million advance appropriation for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This is level funding compared to the amount provided by Congress for both FY 2016 and FY 2017, and is the amount requested by the Administration for FY 2018.