Joyce D.G.R. DE QUEIROZ 1, Nathallia L.A. SALVADOR 1, Marcia F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descriptions of Larvae of California

SUMIDA ET AL.: CALIFORNIA YELLOWTAIL AND OTHER CARANGID LARVAE CalCOFI Rep., Vol. XXVI, 1985 DESCRIPTIONS OF LARVAE OF CALIFORNIA YELLOWTAIL, SERlOLA LALANDI, AND THREE OTHER CARANGIDS FROM THE EASTERN TROPICAL PACIFIC: CHLOROSCOMBRUS ORQUETA, CARANX CABALLUS, AND CARANX SEXFASClATUS BARBARA Y. SUMIDA, ti. GEOFFREY MOSER. AND ELBERT H. AHLSTROM National Marine Fisheries Service Southwest Fisheries Center P.O. Box 271 La Jolla. California 92038 ABSTRACT southern California and Baja California, and it briefly Larvae are described for four species of jacks, fami- supported a commercial fishery during the 1950s ly Carangidae. Three of these, Seriola lalandi (Cali- (MacCall et al. 1976). Larvae of Seriola species from fornia yellowtail), Chloroscombrus orqueta, and other regions of the world have been described (see Carum caballus, occur in the CalCOFI region. A literature review in Laroche et al. 1984), but larvae of fourth species, Caranx sexfasciatus, occurs from eastern Pacific Seriola lalandi have not previously Mazatlan, Mexico, to Panama. Species are distin- been described’. This paper also describes larvae of guished by a combination of morphological, pigmen- two other carangids, Chloroscombrus orqueta and tary, and meristic characters. Larval body morphs Caranx caballus, occurring in the CalCOFI region, range from slender S. lalandi, with a relatively elon- and a third carangid, Caranx sexfasciatus, which gate gut, to deep-bodied C. sexfasciatus, with a occurs to the south. triangular gut mass. Pigmentation patterns are charac- teristic for early stages of each species, but all except MATERIALS AND METHODS C. orqueta become heavily pigmented in late stages of Larvae used in this work were obtained from var- development. -

BIO 313 ANIMAL ECOLOGY Corrected

NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SCHOOL OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COURSE CODE: BIO 314 COURSE TITLE: ANIMAL ECOLOGY 1 BIO 314: ANIMAL ECOLOGY Team Writers: Dr O.A. Olajuyigbe Department of Biology Adeyemi Colledge of Education, P.M.B. 520, Ondo, Ondo State Nigeria. Miss F.C. Olakolu Nigerian Institute for Oceanography and Marine Research, No 3 Wilmot Point Road, Bar-beach Bus-stop, Victoria Island, Lagos, Nigeria. Mrs H.O. Omogoriola Nigerian Institute for Oceanography and Marine Research, No 3 Wilmot Point Road, Bar-beach Bus-stop, Victoria Island, Lagos, Nigeria. EDITOR: Mrs Ajetomobi School of Agricultural Sciences Lagos State Polytechnic Ikorodu, Lagos 2 BIO 313 COURSE GUIDE Introduction Animal Ecology (313) is a first semester course. It is a two credit unit elective course which all students offering Bachelor of Science (BSc) in Biology can take. Animal ecology is an important area of study for scientists. It is the study of animals and how they related to each other as well as their environment. It can also be defined as the scientific study of interactions that determine the distribution and abundance of organisms. Since this is a course in animal ecology, we will focus on animals, which we will define fairly generally as organisms that can move around during some stages of their life and that must feed on other organisms or their products. There are various forms of animal ecology. This includes: • Behavioral ecology, the study of the behavior of the animals with relation to their environment and others • Population ecology, the study of the effects on the population of these animals • Marine ecology is the scientific study of marine-life habitat, populations, and interactions among organisms and the surrounding environment including their abiotic (non-living physical and chemical factors that affect the ability of organisms to survive and reproduce) and biotic factors (living things or the materials that directly or indirectly affect an organism in its environment). -

Redalyc.Stomach Contents of the Pacific Sharpnose Shark

Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research E-ISSN: 0718-560X [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Chile Osuna-Peralta, Yolene R.; Voltolina, Domenico; Morán-Angulo, Ramón E.; Márquez-Farías, J. Fernando Stomach contents of the Pacific sharpnose shark, Rhizoprionodon longurio (Carcharhiniformes, Carcharhinidae) in the southeastern Gulf of California Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research, vol. 42, núm. 3, 2014, pp. 438-444 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Valparaiso, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=175031375005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res., 42(3): 438-44Stomach4, 2014 contents of Rhizoprionodon longurio in the Gulf of California 438 1 DOI: 103856/vol42-issue3-fulltext-5 Research Article Stomach contents of the Pacific sharpnose shark, Rhizoprionodon longurio (Carcharhiniformes, Carcharhinidae) in the southeastern Gulf of California Yolene R. Osuna-Peralta1, Domenico Voltolina2 Ramón E. Morán-Angulo1 & J. Fernando Márquez-Farías1 1Facultad de Ciencias del Mar, Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa Paseo Claussen s/n, Col. Los Pinos, CP 82000, Mazatlán, Sinaloa, México 2Laboratorio UAS-CIBNOR, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste Ap. Postal 1132, CP 82000, Mazatlán, Sinaloa, México ABSTRACT. The feeding habits of the sharpnose shark Rhizoprionodon longurio of the SE Gulf of California are described using the stomach contents of 250 specimens (135 males and 115 females) obtained weekly from December 2007 to March 2008 in the two main landing sites of the artisanal fishing fleet of Mazatlan. -

Brazilian Sardinella Brazil, Southwest Atlantic Purse Seines

Brazilian sardinella Sardinella brasiliensis © Brazil, Southwest Atlantic Purse seines June 14, 2018 Seafood Watch Consulting Researcher Disclaimer Seafood Watch® strives to have all Seafood Reports reviewed for accuracy and completeness by external scientists with expertise in ecology, fisheries science and aquaculture. Scientific review, however, does not constitute an endorsement of the Seafood Watch program or its recommendations on the part of the reviewing scientists. Seafood Watch is solely responsible for the conclusions reached in this report. Seafood Watch Standard used in this assessment: Standard for Fisheries vF3 Table of Contents About. Seafood. .Watch . 3. Guiding. .Principles . 4. Summary. 5. Final. Seafood. .Recommendations . 6. Introduction. 7. Assessment. 10. Criterion. 1:. .Impacts . on. the. Species. Under. Assessment. .10 . Criterion. 2:. .Impacts . on. Other. Species. .12 . Criterion. 3:. .Management . Effectiveness. .20 . Criterion. 4:. .Impacts . on. the. Habitat. .and . Ecosystem. .23 . Acknowledgements. 26. References. 27. Appendix. A:. Extra. .By . Catch. .Species . 31. 2 About Seafood Watch Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch program evaluates the ecological sustainability of wild-caught and farmed seafood commonly found in the United States marketplace. Seafood Watch defines sustainable seafood as originating from sources, whether wild-caught or farmed, which can maintain or increase production in the long-term without jeopardizing the structure or function of affected ecosystems. Seafood Watch makes its science-based recommendations available to the public in the form of regional pocket guides that can be downloaded from www.seafoodwatch.org. The program’s goals are to raise awareness of important ocean conservation issues and empower seafood consumers and businesses to make choices for healthy oceans. -

Influence of Oceanographic Conditions on Abundance and Distribution of Post-Larval and Juvenile Carangid Fishes in the Northern Gulf of Mexico

Received: 19 August 2016 | Accepted: 26 January 2017 DOI: 10.1111/fog.12214 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Influence of oceanographic conditions on abundance and distribution of post-larval and juvenile carangid fishes in the northern Gulf of Mexico John A. Mohan1 | Tracey T. Sutton2 | April B. Cook2 | Kevin M. Boswell3 | R. J. David Wells1,4 1Department of Marine Biology, Texas A&M University at Galveston, Galveston, Abstract TX, USA Relationships between abundance of post-larval and juvenile carangid (jacks) fishes 2Department of Marine and Environmental and physical oceanographic conditions were examined in the northern Gulf of Mex- Sciences, Nova Southeastern University, Dania Beach, FL, USA ico (GoM) in 2011 with high freshwater input from the Mississippi River. General- 3Department of Biological Sciences, Florida ized additive models (GAMs) were used to explore complex relationships between International University, North Miami, FL, USA carangid abundance and physical oceanographic data of sea surface temperature 4Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (SST), sea surface height anomaly (SSHA) and salinity. The five most abundant car- Sciences, Texas A&M University, College angid species collected were: Selene setapinnis (34%); Caranx crysos (30%); Caranx Station, TX, USA hippos (10%); Chloroscombrus chrysurus (9%) and Trachurus lathami (8%). Post-larval Correspondence carangids (median standard length [SL] = 10 mm) were less abundant during the John A. Mohan Email: [email protected] spring and early summer, but more abundant during the late summer and fall, sug- gesting summer to fall spawning for most species. Juvenile carangid (median Funding information Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative; National SL = 23 mm) abundance also increased between the mid-summer and early fall. -

Intrinsic Vulnerability in the Global Fish Catch

The following appendix accompanies the article Intrinsic vulnerability in the global fish catch William W. L. Cheung1,*, Reg Watson1, Telmo Morato1,2, Tony J. Pitcher1, Daniel Pauly1 1Fisheries Centre, The University of British Columbia, Aquatic Ecosystems Research Laboratory (AERL), 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada 2Departamento de Oceanografia e Pescas, Universidade dos Açores, 9901-862 Horta, Portugal *Email: [email protected] Marine Ecology Progress Series 333:1–12 (2007) Appendix 1. Intrinsic vulnerability index of fish taxa represented in the global catch, based on the Sea Around Us database (www.seaaroundus.org) Taxonomic Intrinsic level Taxon Common name vulnerability Family Pristidae Sawfishes 88 Squatinidae Angel sharks 80 Anarhichadidae Wolffishes 78 Carcharhinidae Requiem sharks 77 Sphyrnidae Hammerhead, bonnethead, scoophead shark 77 Macrouridae Grenadiers or rattails 75 Rajidae Skates 72 Alepocephalidae Slickheads 71 Lophiidae Goosefishes 70 Torpedinidae Electric rays 68 Belonidae Needlefishes 67 Emmelichthyidae Rovers 66 Nototheniidae Cod icefishes 65 Ophidiidae Cusk-eels 65 Trachichthyidae Slimeheads 64 Channichthyidae Crocodile icefishes 63 Myliobatidae Eagle and manta rays 63 Squalidae Dogfish sharks 62 Congridae Conger and garden eels 60 Serranidae Sea basses: groupers and fairy basslets 60 Exocoetidae Flyingfishes 59 Malacanthidae Tilefishes 58 Scorpaenidae Scorpionfishes or rockfishes 58 Polynemidae Threadfins 56 Triakidae Houndsharks 56 Istiophoridae Billfishes 55 Petromyzontidae -

Guide to the Coastal Marine Fishes of California

STATE OF CALIFORNIA THE RESOURCES AGENCY DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME FISH BULLETIN 157 GUIDE TO THE COASTAL MARINE FISHES OF CALIFORNIA by DANIEL J. MILLER and ROBERT N. LEA Marine Resources Region 1972 ABSTRACT This is a comprehensive identification guide encompassing all shallow marine fishes within California waters. Geographic range limits, maximum size, depth range, a brief color description, and some meristic counts including, if available: fin ray counts, lateral line pores, lateral line scales, gill rakers, and vertebrae are given. Body proportions and shapes are used in the keys and a state- ment concerning the rarity or commonness in California is given for each species. In all, 554 species are described. Three of these have not been re- corded or confirmed as occurring in California waters but are included since they are apt to appear. The remainder have been recorded as occurring in an area between the Mexican and Oregon borders and offshore to at least 50 miles. Five of California species as yet have not been named or described, and ichthyologists studying these new forms have given information on identification to enable inclusion here. A dichotomous key to 144 families includes an outline figure of a repre- sentative for all but two families. Keys are presented for all larger families, and diagnostic features are pointed out on most of the figures. Illustrations are presented for all but eight species. Of the 554 species, 439 are found primarily in depths less than 400 ft., 48 are meso- or bathypelagic species, and 67 are deepwater bottom dwelling forms rarely taken in less than 400 ft. -

Fish Species Transshipped at Sea (Saiko Sh) in Ghana with a Note On

Fish species transshipped at sea (Saiko ƒsh) in Ghana with a note on implications for marine conservation Denis Worlanyo Aheto ( [email protected] ) Centre for Coastal Management - Africa Centre of Excellence in Coastal Resilience (ACECoR), University of Cape Coast, Ghana https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5722-1363 Isaac Okyere ( [email protected] ) Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, School of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Coast, Ghana https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8725-1555 Noble Kwame Asare Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, School of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Coast, Ghana Jennifer Eshilley Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, School of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Coast, Ghana Justice Odoiquaye Odoi Nature Today, A25 Standards Estates, Sakumono, Tema, Ghana Research Article Keywords: Fish transshipment, saiko, IUU ƒshing, Marine Conservation, Sustainability, Ghana DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-41329/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/18 Abstract Increasing global seafood demand over the last couple of decades has resulted in overexploitation of certain ƒsh species by both industrial and small-scale artisanal ƒshers. This phenomenon has threatened the livelihoods and food security of small-scale ƒshing communities especially in the West African sub- region. In Ghana, ƒsh transshipment (locally referred to as saiko) has been catalogued as one more negative practice that is exacerbating an already dire situation. The goal of this study was to characterise transshipped ƒsh species landed in Ghana on the basis of composition, habitat of origin, maturity and conservation status on the IUCN list of threatened species to enhance understanding of the ecological implications of the practice and inform regulatory enforcement and policy formulation. -

St. Lucie, Units 1 and 2

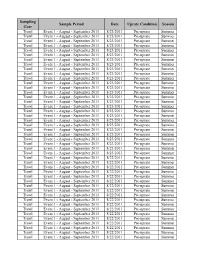

Sampling Sample Period Date Uprate Condition Season Gear Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event -

An Ecological Characterization of the Tampa Bay Watershed

Biological Report 90(20) December 1990 An Ecological Characterization of the Tampa Bay Watershed Fish and Wildlife Service and Minerals Management Service u.s. Department of the Interior Chapter 6. Fauna N. Scott Schomer and Paul Johnson 6.1 Introduction on each species, as well as the limited scope.of this document, often excludes such information from our Generally speaking, animal species utilize only a discussion. Where possible, references to more limited number of habitats within a restricted geo detailed infonnation on local fish and wildlife condi graphic range. Factors that regulate habitat use and tions are included. geographic range include the behavior, physiology, and anatomy ofthe species; competitive, trophic, and 6.2 Invertebrates symbiotic interactions with other species; and forces that influence species dispersion. Such restrictions may be broad, as in the ca.<re of the common crow, 6.2.1 Freshwater Invertebrates which prospers in a wide variety of settings over a Data on freshwater invertebrate communities in va.')t geographic area; or narrow as in the case of the the Tampa Bay area are reported by Cowen et a1. mangrove terrapin, which is found in only one habitat (1974) in the lower Hillsborough River, Cowell et aI. and only in the near tropics of the western hemi (1975) in Lake Thonotosassa; Dames and Moore sphere. Knowledge of animal-species occurrence (1975) in the Alafia and Little Manatee Rivers; and within habitat') is fundamental to understanding and Ross and Jones (1979) at numerous locations within managing -

Marine Turtle Newsletter Issue Number 137 April 2013

Marine Turtle Newsletter Issue Number 137 April 2013 Green turtle incidentally captured in a fishing weir, along the coast of Almofala, Ceara, Brazil (see pages 5-9; photo: Image Bank - Projeto TAMAR/Ceará-Brazil). Articles Unraveling Behavioral Patterns of Foraging Hawksbill and Green Turtles Using Photo-ID...........A Chassagneux et al. Sea Turtles in the Waters of Almofala, Ceará, in Northeastern Brazil, 2001–2010..............................EHSM Lima et al. Evidence of Long Distance Homing in a Displaced Juvenile Kemp’s Ridley Sea Turtle..............................AT Coleman New Evidence of Nesting Dermochelys coriacea (Tortuga Achepa) at Iporoimao-Utareo Beaches, Guajira, Colombia..............................................................WJ Borrero Avellaneda et al. Project Profile Announcement Recent Publications Marine Turtle Newsletter No. 137, 2013 - Page 1 ISSN 0839-7708 Editors: Managing Editor: Kelly R. Stewart Matthew H. Godfrey Michael S. Coyne NOAA-National Marine Fisheries Service NC Sea Turtle Project SEATURTLE.ORG Southwest Fisheries Science Center NC Wildlife Resources Commission 1 Southampton Place 3333 N. Torrey Pines Ct. 1507 Ann St. Durham, NC 27705, USA La Jolla, California 92037 USA Beaufort, NC 28516 USA E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +1 858-546-7003 Fax: +1 919 684-8741 Founding Editor: Nicholas Mrosovsky University of Toronto, Canada Editorial Board: Brendan J. Godley & Annette C. Broderick (Editors Emeriti) Nicolas J. Pilcher University of Exeter in Cornwall, UK Marine Research Foundation, Malaysia George H. Balazs Manjula Tiwari National Marine Fisheries Service, Hawaii, USA National Marine Fisheries Service, La Jolla, USA Alan B. Bolten ALan F. Rees University of Florida, USA University of Exeter in Cornwall, UK Robert P. -

South Atlantic Regional Fish Monitoring of Restored Oyster Habitat Along the Southeastern US Coast

South Atlantic Regional Fish Monitoring of Restored Oyster Habitat along the Southeastern US Coast Introduction Oyster reefs are a critical component of coastal systems in the southeast United States. They are most commonly found within estuaries which are where the ocean and rivers meet, creating brackish water. Within this brackish water, they provide structural habitat for a variety of vertebrates and invertebrates, provide food, help maintain water quality through filtration, and mitigate shoreline erosion (Grabowski and Peterson 2007, Callihan et al. 2016, Baggett et al. 2014, zu Ermgassen et al. 2016, Hancock and zu Ermgassen 2019). Oyster reefs are a well-studied, crucial nursery habitat for many commercially and recreationally important species (SCDNR, Callihan et al. 2016, zu Ermgassen et al. 2016, Hancock and zu Ermgassen 2019). Species ranging from blue crab to flounder and many more rely on oyster reefs at some stage of their life cycle (NRC). Juvenile species seek refuge from predators within the reef structure (SCDNR, zu Ermgassen et al. 2016, Hancock and zu Ermgassen 2019). Many of these fish feed on larvae and larval animals within the oyster reefs, and this allows them to grow and reproduce, or eventually become prey for larger fishes (SCDNR). Oyster reefs serve as a nursery habitat in another form such that some species attach their eggs to the underside of oyster shells (SCDNR, zu Ermgassen et al. 2016). In comparison to unstructured sediment, which usually replaces destroyed oyster reef habitat, the use of oyster reefs as a nursery habitat leads to enhanced fish production. (Hancock and zu Ermgassen 2019).