A Review of Two Decades of Conservation Efforts on Tigers, Co-Predators and Prey at the Junction of Three Global Biodiversity Ho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

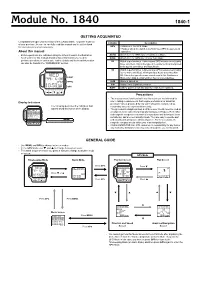

Module No. 1840 1840-1

Module No. 1840 1840-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out Indicator Description of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand for later reference when necessary. GPS • Watch is in the GPS Mode. • Flashes when the watch is performing a GPS measurement About this manual operation. • Button operations are indicated using the letters shown in the illustration. AUTO Watch is in the GPS Auto or Continuous Mode. • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to SAVE Watch is in the GPS One-shot or Auto Mode. perform operations in each mode. Further details and technical information 2D Watch is performing a 2-dimensional GPS measurement (using can also be found in the “REFERENCE” section. three satellites). This is the type of measurement normally used in the Quick, One-Shot, and Auto Mode. 3D Watch is performing a 3-dimensional GPS measurement (using four or more satellites), which provides better accuracy than 2D. This is the type of measurement used in the Continuous LIGHT Mode when data is obtained from four or more satellites. MENU ALM Alarm is turned on. SIG Hourly Time Signal is turned on. GPS BATT Battery power is low and battery needs to be replaced. Precautions • The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for Display Indicators use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as The following describes the indicators that reasonably accurate representations only. -

Snow Leopard Survival Strategy 2014

Snow Leopard Survival Strategy Revised Version 2014.1 Snow Leopard Network 1 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Snow Leopard Network concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Copyright: © 2014 Snow Leopard Network, 4649 Sunnyside Ave. N. Suite 325, Seattle, WA 98103. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Snow Leopard Network (2014). Snow Leopard Survival Strategy. Revised 2014 Version Snow Leopard Network, Seattle, Washington, USA. Website: http://www.snowleopardnetwork.org/ The Snow Leopard Network is a worldwide organization dedicated to facilitating the exchange of information between individuals around the world for the purpose of snow leopard conservation. Our membership includes leading snow leopard experts in the public, private, and non-profit sectors. The main goal of this organization is to implement the Snow Leopard Survival Strategy (SLSS) which offers a comprehensive analysis of the issues facing snow leopard conservation today. Cover photo: Camera-trapped snow leopard. © Snow Leopard -

Construction of Water Environment Carrying Capacity

International Conference on Economics, Social Science, Arts, Education and Management Engineering (ESSAEME 2015) Construction of Water Environment Carrying Capacity Evaluation Model in Erhai River Basin Liu Wei-Hong1,2, Zhang Cheng-Gui1,3 , Gao Peng-Fei1,3,Liu Heng1,3,Song Yan-Qiu1, Huang Bi-Sheng4, Yang Jian-Fang*1,5 1 The Key Laboratory of Medical Insects and Spiders Resources for Development & Utilization at Yunnan Province; Dali University, Dali 671000, Yunnan Province, China; 2The Libraries of Dali University, Dali 671000, Yunnan Province, China; 3 National-local Joint Engineering Research Center of Entomoceutics, Dali 671000, Yunnan Province, China 4Department of Agriculture and Biological Sciences,Dali University, Dali 671003, People’s Republic of China 5School of Foreign Languages, Dali University, Dali 671000, Yunnan Province, China; Liu Wei-Hong and Zhang Cheng-Gui have contributed equally to this work. *Corresponding author: Associate Professor Yang Jian-Fang The Key Laboratory of Medical Insects and Spiders Resources for Development & Utilization at Yunnan Province; Dali University, Dali 671000, Yunnan Province, China; E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Water environment carrying capacity, Evaluation model, Erhai River basin. Abstract. With the acceleration of urbanization and increasing energy consumption in China, the intensity of pollution emission the pollution load is increasing significantly. In many rivers, the main pollutant load is much more than the environmental capacity of the water, resulting in the destruction of the structure and function of the river basin. This paper puts forward the concept of water environment carrying capacity, and constructs the basic model of calculating water environment carrying capacity, and then takes ErhaiRiver as an example to calculate the carrying capacity of water environment in order to provide reference for relevant researchers. -

Changing Pattern of Spatio-Social Interrelationship of Hunting Community in Upper Dibang Valley

Changing Pattern of Spatio-Social Interrelationship of Hunting Community in Upper Dibang Valley, Arunachal Pradesh A Dissertation submitted To Sikkim University In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy By MOHAN SHARMA Department of Geography School of Human Sciences February 2020 Date: 07/02/2020 DECLARATION I, Mohan Sharma, hereby declare that the research work embodied in the Dissertation titled “Changing Pattern of Spatio-Social Interrelationship of Hunting Community in Upper Dibang Valley, Arunachal Pradesh” submitted to Sikkim University for the award of the Degree of Master of Philosophy, is my original work. The thesis has not been submitted for any other degree of this University or any other University. (Mohan Sharma) Roll Number: 18MPGP01 Regd. No.: 18MPhil/GOG/01 Name of the Department: Geography Name of the School: Human Sciences Date: 07/02/2020 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation titled “Changing Pattern of Spatio-Social Interrelationship of Hunting Community in Upper Dibang Valley, Arunachal Pradesh” submitted to Sikkim University for the partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Department of Geography, embodies the result of bonafide research work carried out by Mr. Mohan Sharma under our guidance and supervision. No part of the dissertation has been submitted for any other degree, diploma, associateship and fellowship. All the assistance and help received during the course of the investigation have been duly acknowledged by him. We recommend -

Government of Arunachal Pradesh Directorate of Higher & Technical

GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH DIRECTORATE OF HIGHER & TECHNICAL EDUCATION ITANAGAR No. ED/HE-40/JEE/2020 Dated: Itanagar, the 17th Nov’ 2020 FIRST OF OF SEAT ALLOTMENT FOR PCB GROUP COURSES Based on the rank in NEET(UG)2020 and choices submitted, the allotment of seat in the Academic Program and Institute shown against each has been made in the 1st Round of seat allotment for the various PCB Group courses. Candidates are therefore required to complete all the steps mandatorily as per the given schedule of PCB Group Counseling 2020 otherwise the allotment of seat would be cancelled and they will have no right, whatsoever, over the seat allotted. CATEGORY – I UG UG SL. UG NEET NEET NEET NAME OF CANDIDATE COURSE ALLOTTED NAME OF INSTITUTE NO. ROLL NO SCORE RANK 1 1301003246 596 21906 PUNYO SANGO CHOICE NOT SUBMITTED North East Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Health and Medical 2 1301002318 565 39006 YIKAR NGUKI MBBS Sciences, Shillong North East Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Health and Medical 3 1301010116 564 39496 NIAGAM PIGIA MBBS Sciences, Shillong North East Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Health and Medical 4 1301002114 560 42144 TOKO YALAM MBBS Sciences, Shillong North East Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Health and Medical 5 1301008218 555 45495 PERSIA BUI MBBS Sciences, Shillong 6 1301010224 551 47988 HONKAP WANGJEN MBBS Tomo Riba Institute of Health and Medical Sciences, Naharlagan 7 1301007271 524 67278 TEIKESI MINING MBBS Regional Institute of Medical Science, Imphal 8 1301005093 514 75524 NANI NUNIA MBBS -

Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi

by Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi Preface About the Author In the whole world, there are more than 30,000 species Keshav Ravi is a caring and compassionate third grader threatened with extinction today. One prominent way to who has been fascinated by nature throughout his raise awareness as to the plight of these animals is, of childhood. Keshav is a prolific reader and writer of course, education. nonfiction and is always eager to share what he has learned with others. I have always been interested in wildlife, from extinct dinosaurs to the lemurs of Madagascar. At my ninth Outside of his family, Keshav is thrilled to have birthday, one personal writing project I had going was on the support of invested animal advocates, such as endangered wildlife, and I had chosen to focus on India, Carole Hyde and Leonor Delgado, at the Palo Alto the country where I had spent a few summers, away from Humane Society. my home in California. Keshav also wishes to thank Ernest P. Walker’s Just as I began to explore the International Union for encyclopedia (Walker et al. 1975) Mammals of the World Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List species for for inspiration and the many Indian wildlife scientists India, I realized quickly that the severity of threat to a and photographers whose efforts have made this variety of species was immense. It was humbling to then work possible. realize that I would have to narrow my focus further down to a subset of species—and that brought me to this book on the Endangered Mammals of India. -

The Challenge of Peace in Nagaland

India talks with Naga rebels The challenge of peace in Nagaland BY RUPAK CHATTOPADHYAY There are times when the of the most complex. Government of India and armed separatists are not only willing to talk The Nagas before 1975 but to agree on something. That happened on January 31 in Bangkok There are seventeen major and an when both India and one such group, equal number of smaller Naga tribes, the National Socialist Council of each with its own recognizable dialect Nagaland — Isaac Muivah faction, and customs, linked traditionally by a known as NSCN-IM, extended an shared way of life and religious eight-year-old ceasefire for another In New Delhi, the Secretary-General of India's practices, and indeed more recently by six months as both sides attempt to upper house of parliament receives members of Christianity. There are more than 14 find a solution to this long-running the Nagaland Legislative Assembly. tribes that make up the Nagas. Tribal insurgency. conflicts have complicated the process The Naga revolt is centred in the state of Nagaland – one of of peacemaking in the state of seven in North East India. They are known as the “seven Nagaland, and other Naga inhabited areas, over the years. sisters”: Nagaland, Assam, Manipur, Tripura, Meghalaya, Nagas also reside in the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram, which are among the Assam and Manipur. most neglected and underdeveloped parts of India. The The Naga rebellion dates back to India’s independence in North East is a remote region connected to the rest of India 1947, when separatist sentiments represented by A. -

Histrical Background Changlang District Covered with Picturesque Hills Lies in the South-Eastern Corner of Arunachal Pradesh, Northeast India

Histrical Background Changlang District covered with picturesque hills lies in the south-eastern corner of Arunachal Pradesh, northeast India. It has an area of 4,662 sqr. Km and a population of 1,48,226 persons as per 2011 Census. According to legend the name Changlang owes its origin to the local word CHANGLANGKAN which means a hilltop where people discovered the poisonous herb, which is used for poisoning fish in the river. Changlang District has reached the stage in its present set up through a gradual development of Administration. Prior to 14th November 1987, it was a part of Tirap District. Under the Arunachal Pradesh Reorganization of Districts Amendment Bill, 1987,the Government of Arunachal Pradesh, formally declared the area as a new District on 14th November 1987 and became 10th district of Arunachal Pradesh. The legacy of Second World War, the historic Stilwell Road (Ledo Road), which was constructed during the Second World War by the Allied Soldiers from Ledo in Assam, India to Kunming, China via hills and valleys of impenetrable forests of north Burma (Myanmar) which section of this road is also passed through Changlang district of Arunachal Pradesh and remnant of Second World War Cemetery one can see at Jairampur – Nampong road. Location and Boundary The District lies between the Latitudes 26°40’N and 27°40’N, and Longitudes 95°11’E and 97°11’E .It is bounded by Tinsukia District of Assam and Lohit District of Arunachal Pradesh in the north, by Tirap District in the west and by Myanmar in the south-east. -

Ancient Genomes Reveal Tropical Bovid Species in the Tibetan Plateau Contributed to the Prevalence of Hunting Game Until the Late Neolithic

Ancient genomes reveal tropical bovid species in the Tibetan Plateau contributed to the prevalence of hunting game until the late Neolithic Ningbo Chena,b,1, Lele Renc,1, Linyao Dud,1, Jiawen Houb,1, Victoria E. Mulline, Duo Wud, Xueye Zhaof, Chunmei Lia,g, Jiahui Huanga,h, Xuebin Qia,g, Marco Rosario Capodiferroi, Alessandro Achillii, Chuzhao Leib, Fahu Chenj, Bing Sua,g,2, Guanghui Dongd,j,2, and Xiaoming Zhanga,g,2 aState Key Laboratory of Genetic Resources and Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), 650223 Kunming, China; bKey Laboratory of Animal Genetics, Breeding and Reproduction of Shaanxi Province, College of Animal Science and Technology, Northwest A&F University, 712100 Yangling, China; cSchool of History and Culture, Lanzhou University, 730000 Lanzhou, China; dCollege of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Lanzhou University, 730000 Lanzhou, China; eDepartment of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom; fGansu Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, 730000 Lanzhou, China; gCenter for Excellence in Animal Evolution and Genetics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 650223 Kunming, China; hKunming College of Life Science, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100049 Beijing, China; iDipartimento di Biologia e Biotecnologie “L. Spallanzani,” Università di Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; and jCAS Center for Excellence in Tibetan Plateau Earth Sciences, Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100101 Beijing, China Edited by Zhonghe Zhou, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, and approved September 11, 2020 (received for review June 7, 2020) Local wild bovids have been determined to be important prey on and 3,000 m a.s.l. -

Beijing - Hand-Rearing a Chinese Goral at RZSS Edinburgh Zoo Ceri Robertson

RATEL Vol. 38, No.1., March 2011 pp. 7-14 Beijing - Hand-rearing a Chinese Goral at RZSS Edinburgh Zoo Ceri Robertson Chinese gorals are one of 26 species of the subfamily Caprinae or goat antelope species. They can be found scattered around North India, Burma, South east Siberia and south Thailand. Chinese gorals have very well designed bodies, which allow them to inhabit steep rocky mountainous cliffs, with a range of both evergreen and deciduous forests. As well as the different habitat they can also be found living in various different climates, ranging from dry to moist snowy climates. Physical description vary a little bit between the males and females in that males are a little heavier weighing in at around 28-42kg and females would be around 22-35kg in bodyweight. The height is also a difference between the sexes in that the males are also a little taller than females. Males are around 69-78cm tall and are around 106-117cm in body length. Females as already mentioned, are a little smaller and are around 50 -75cm protocol on new born calves. The calf was tall, however they are both around about the same body removed from the existing outdoor enclosure length with the females being about 106 -118cm in body where her father was still present and placed in a length. heated indoor enclosure. Both sexes are brownish, grey to red in colour, with the The indoor enclosure was a pen in Edinburgh distinctive white patch around the throat area. Also on Zoo’s Pudu House. -

1Ec77e117e2ce3cf999f0ab38d9f

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for RSC Advances. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2018 Electronic supplementary information (ESI) Insights into the role of electrostatics in temperature adaptation: A comparative study of psychrophilic, mesophilic, and thermophilic subtilisin-like serine proteases Yuan-Ling Xia,‡a Jian-Hong Sun,‡a Shi-Meng Ai,b Yi Li,a Xing Du,a Peng Sang,c Li-Quan Yang,c Yun-Xin Fu*a,d and Shu-Qun Liu*a,e aState Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Bio-Resources in Yunnan, Yunnan University, Kunming, Yunnan, P.R. China bDepartment of Applied Mathematics, Yunnan Agricultural University, Kunming, Yunnan, P. R. China cCollege of Agriculture and Biological Science, Dali University, Dali, Yunnan, P. R. China dHuman Genetics Center and Division of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, Texas, USA eKey Laboratory for Tumor molecular biology of High Education in Yunnan Province, School of Life Sciences, Yunnan University, Kunming, Yunnan, P. R. China ‡ These authors contributed equally to this work * Corresponding author Email: [email protected] (YXF), [email protected] (SQL) Fig. S1 Structure-based multiple sequence alignment of the psychrophilic VPR, mesophilic PRK, and thermophilic AQN. Protein secondary structure (SS) is shown below the alignment, with H, E, and L/l representing the -helix (or 3/10 helix), -strand, and loop, respectively. Residue insertion and deletion are denoted by lowercase single-letter amino acid code and ‘-‘, respectively. The charged residues are highlighted in grey. † Table S1 pKa values of histidines in the three protease structures predicted by DelPhiPKa . -

Andhra Pradesh Forestry Project: Forest Restoration and Joint Forest Management in India

Andhra Pradesh Forestry Project: Forest Restoration and Joint Forest Management in India Project Description India’s 1988 forest policy stipulates that forests are to be managed primarily for ecological conservation, and the use of forest resources for local use or non-local industry is of secondary emphasis. In Andhra Pradesh, local people living near forests are forming Vana Samrakshna Samithi (VSS), village organisations dedicated to forest restoration. In partnership with the state forestry department more than 5,000 VSS are working to restore more than 1.2 million hectares of degraded forests. VSS share all of the non-timber forest products (grasses, fuel-wood, fruit, and medicines) amongst themselves, and receive all of the income from the harvest of timber and bamboo. Half of this income is set aside for the future development and maintenance of the forest. In this way the long-term sustainability of the project is protected and government support is only required while the forest returns to a productive state. Ecosystem type The Eastern Highlands Tropical Moist Deciduous Forests are considered globally outstanding for the communities of large vertebrates and intact ecological processes that they support. The region contains 84,000 km2 of intact habitat, some in blocks of more than 5,000 km2. The region is a refuge for many large vertebrates such as wolves (Canis lupus) and gaur (Bos gaurus), and threatened large mammals such as the tiger (Panthera tigris), sloth bear (Melursus ursinus), wild dog (Cuon alpinus), chousingha (Tetracerus quadricornis), blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra), and chinkara (Gazella bennettii). The only endemic mammal is a threatened Rhinolophidae bat, Hipposideros durgadasi.