Gay Is Good ■ 20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

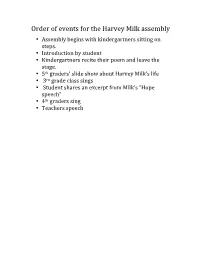

Order of Events for the Harvey Milk Assembly • Assembly Begins with Kindergartners Sitting on Steps

Order of events for the Harvey Milk assembly • Assembly begins with kindergartners sitting on steps. • Introduction by student • Kindergartners recite their poem and leave the stage. • 5th graders’ slide show about Harvey Milk’s life • 3rd grade class sings • Student shares an excerpt from Milk’s “Hope speech” • 4th graders sing • Teachers speech Student 1 Introduction Welcome students of (School Name). Today we will tell you about Harvey Milk, the first gay City Hall supervisor. He has changed many people’s lives that are gay or lesbian. People respect him because he stood up for gay and lesbian people. He is remembered for changing our country, and he is a hero to gay and lesbian people. Fifth Grade Class Slide Show When Harvey Milk was a little boy he loved to be the center of attention. Growing up, Harvey was a pretty normal boy, doing things that all boys do. Harvey was very popular in school and had many friends. However, he hid from everyone a very troubling secret. Harvey Milk was homosexual. Being gay wasn’t very easy back in those days. For an example, Harvey Milk and Joe Campbell had to keep a secret of their gay relationship for six years. Sadly, they broke up because of stress. But Harvey Milk was still looking for a spouse. Eventually, Harvey Milk met Scott Smith and fell in love. Harvey and Scott moved together to the Castro neighborhood of San Francisco, which was a haven for people who were gay, a place where they were respected more easily. Harvey and Scott opened a store called Castro Camera and lived on the top floor. -

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. THEMES The chapters in this section take themes as their starting points. They explore different aspects of LGBTQ history and heritage, tying them to specific places across the country. They include examinations of LGBTQ community, civil rights, the law, health, art and artists, commerce, the military, sports and leisure, and sex, love, and relationships. MAKING COMMUNITY: THE PLACES AND15 SPACES OF LGBTQ COLLECTIVE IDENTITY FORMATION Christina B. Hanhardt Introduction In the summer of 2012, posters reading "MORE GRINDR=FEWER GAY BARS” appeared taped to signposts in numerous gay neighborhoods in North America—from Greenwich Village in New York City to Davie Village in Vancouver, Canada.1 The signs expressed a brewing fear: that the popularity of online lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) social media—like Grindr, which connects gay men based on proximate location—would soon replace the bricks-and-mortar institutions that had long facilitated LGBTQ community building. -

Thematic Review: American Gay Rights Movement Directions and Obje

Name:_____________________________________ Class Period:______ Thematic Review: American Gay Rights Movement Although the topic of homosexuality continues to ignite passionate debate and is often omitted from history discussions due to the sensitivity of the topic, it is important to consider gays and lesbians when defining and analyzing modern American identity. The purpose of this activity is to review the struggle for respect, dignity, and equal protection under the law that so many have fought for throughout American history. Racial minorities… from slaves fighting for freedom to immigrants battling for opportunity… to modern-day racial and ethnic minorities working to overcome previous and current inequities in the American system. Women… fighting for property rights, education, suffrage, divorce, and birth control. Non- Protestants… from Catholics, Mormons, and Jews battling discrimination to modern day Muslims and others seeking peaceful co-existence in this “land of the free.” Where do gays and lesbians fit in? Once marginalized as criminals and/or mentally ill, they are increasingly being included in the “fabric” we call America. From the Period 8 Content Outline: Stirred by a growing awareness of inequalities in American society and by the African American civil rights movement, activists also addressed issues of identity and social justice, such as gender/sexuality and ethnicity. Activists began to question society’s assumptions about gender and to call for social and economic equality for women and for gays and lesbians. Directions and Objectives: Review the events in the Gay Rights Thematic Review Timeline, analyze changes in American identity, and make connections to other historically significant events occurring along the way. -

Sip-In" That Drew from the Civil Rights Movement by History.Com, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 11.07.19 Word Count 887 Level 1020L

The gay "sip-in" that drew from the civil rights movement By History.com, adapted by Newsela staff on 11.07.19 Word Count 887 Level 1020L Image 1. A bartender in Julius's Bar refuses to serve John Timmins, Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell and Randy Wicker, members of the Mattachine Society, an early American gay rights group, who were protesting New York liquor laws that prevented serving gay customers on April 21, 1966. Photo from: Getty Images/Fred W. McDarrah. In 1966, on a spring afternoon in Greenwich Village, three men set out to change the political and social climate of New York City. After having gone from one bar to the next, the men reached a cozy tavern named Julius'. They approached the bartender, proclaimed they were gay and then requested a drink, but were promptly denied service. The trio had accomplished their goal: their "sip-in" had begun. The men belonged to the Mattachine Society, an early organization dedicated to fighting for gay rights. They wanted to show that bars in the city discriminated against gay people. Discrimination against the gay community was a common practice at the time. Still, this discrimination was less obvious than the discriminatory Jim Crow laws in the South that forced racial segregation. Bartenders Refused Service To Gay Couples This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. A person's sexual orientation couldn't be detected as easily as a person's sex or race. With that in mind, the New York State Liquor Authority, a state agency that controls liquor sales, took action. -

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lvovsky, Anna. 2015. Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463142 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 A dissertation presented by Anna Lvovsky to The Committee on Higher Degrees in the History of American Civilization in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of American Civilization Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 – Anna Lvovsky All rights reserved. Advisor: Nancy Cott Anna Lvovsky Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 Abstract This dissertation tracks how urban police tactics against homosexuality participated in the construction, ratification, and dissemination of authoritative public knowledge about gay men in the -

Raise the Curtain

JAN-FEB 2016 THEAtlanta OFFICIAL VISITORS GUIDE OF AtLANTA CoNVENTI ON &Now VISITORS BUREAU ATLANTA.NET RAISE THE CURTAIN THE NEW YEAR USHERS IN EXCITING NEW ADDITIONS TO SOME OF AtLANTA’S FAVORITE ATTRACTIONS INCLUDING THE WORLDS OF PUPPETRY MUSEUM AT CENTER FOR PUPPETRY ARTS. B ARGAIN BITES SEE PAGE 24 V ALENTINE’S DAY GIFT GUIDE SEE PAGE 32 SOP RTS CENTRAL SEE PAGE 36 ATLANTA’S MUST-SEA ATTRACTION. In 2015, Georgia Aquarium won the TripAdvisor Travelers’ Choice award as the #1 aquarium in the U.S. Don’t miss this amazing attraction while you’re here in Atlanta. For one low price, you’ll see all the exhibits and shows, and you’ll get a special discount when you book online. Plan your visit today at GeorgiaAquarium.org | 404.581.4000 | Georgia Aquarium is a not-for-profit organization, inspiring awareness and conservation of aquatic animals. F ATLANTA JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2016 O CONTENTS en’s museum DR D CHIL ENE OP E Y R NEWL THE 6 CALENDAR 36 SPORTS OF EVENTS SPORTS CENTRAL 14 Our hottest picks for Start the year with NASCAR, January and February’s basketball and more. what’S new events 38 ARC AROUND 11 INSIDER INFO THE PARK AT our Tips, conventions, discounts Centennial Olympic Park on tickets and visitor anchors a walkable ring of ATTRACTIONS information booth locations. some of the city’s best- It’s all here. known attractions. Think you’ve already seen most of the city’s top visitor 12 NEIGHBORHOODS 39 RESOURCE Explore our neighborhoods GUIDE venues? Update your bucket and find the perfect fit for Attractions, restaurants, list with these new and improved your interests, plus special venues, services and events in each ’hood. -

The Stonewall Riots 2/5/16 10:34 PM Page Iii DM - the Stonewall Riots 2/5/16 10:34 PM Page V

DM - The Stonewall Riots 2/5/16 10:34 PM Page iii DM - The Stonewall Riots 2/5/16 10:34 PM Page v Table of Contents Preface . vii How to Use This Book . xi Research Topics for Defining Moments: The Stonewall Riots . xiii NARRATIVE OVERVIEW Prologue . 3 Chapter 1: Homophobia and Discrimination . 9 Chapter 2: The LGBT Experience in New York City . 23 Chapter 3: Raid on the Stonewall Inn . 37 Chapter 4: Growth of the LGBT Rights Movement . 53 Chapter 5: The AIDS Crisis and the Struggle for Acceptance . 65 Chapter 6: Progress in the Courts . 79 Chapter 7: Legacy of the Stonewall Riots . 95 BIOGRAPHIES Marsha P. Johnson (1945–1992) . 107 Stonewall Riot Participant and Transgender Rights Activist Frank Kameny (1925–2011) . 111 Father of the LGBT Rights Movement Dick Leitsch (1935–) . 116 LGBT Rights Activist and New York Mattachine Society Leader v DM - The Stonewall Riots 2/9/16 2:06 PM Page vi Defining Moments: The Stonewall Riots Seymour Pine (1919–2010) . 120 New York Police Inspector Who Led the Stonewall Inn Raid Sylvia Rivera (1951–2002) . 123 Stonewall Riot Participant and Transgender Rights Activist Craig Rodwell (1940–1993) . 127 Bookstore Owner, Activist, and Stonewall Riot Participant Martha Shelley (1943–) . 131 LGBT Rights Activist and Witness to the Stonewall Riots Howard Smith (1936–2014) . 135 Journalist Who Reported from Inside the Stonewall Inn PRIMARY SOURCES A Medical Journal Exhibits Homophobia . 141 The Kinsey Report Explodes Myths about Homosexuality . 143 Lucian Truscott Covers the Stonewall Riots . 149 Howard Smith Reports from Inside the Bar . 154 Media Coverage Angers LGBT Activists . -

Lorne Bair :: Catalog 21

LORNE BAIR :: CATALOG 21 1 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 2621 Daniel Terrace Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with order and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ standards of professionalism and ethics. PART ONE African American History & Literature ITEMS 1-54 PART TWO Radical, Social, & Proletarian Literature ITEMS 55-92 PART THREE Graphics, Posters & Original Art ITEMS 93-150 PART FOUR Social Movements & Radical History ITEMS 151-194 2 PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. CUNARD, Nancy (ed.) Negro Anthology Made by Nancy Cunard 1931-1933. London: Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co., 1934. -

This Is Not a Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections Walter Gainor Moore Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2015 This Is Not A Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections Walter Gainor Moore Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Recommended Citation Moore, Walter Gainor, "This Is Not A Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections" (2015). Open Access Dissertations. 1421. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/1421 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School Form 30 Updated 1/15/2015 PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Walter Gainor Moore Entitled THIS IS NOT A DISSERTATION. (NEO)NEO-BOHEMIAN CONNECTIONS For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Is approved by the final examining committee: Lance A. Duerfahrd Chair Daniel Morris P. Ryan Schneider Rachel L. Einwohner To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material. Approved by Major Professor(s): Lance A. Duerfahrd Approved by: Aryvon Fouche 9/19/2015 Head of the Departmental Graduate Program Date THIS IS NOT A DISSERTATION. (NEO)NEO-BOHEMIAN CONNECTIONS A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Walter Moore In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Lance, my advisor for this dissertation, for challenging me to do better; to work better—to be a stronger student. -

Dp Harvey Milk

1 Focus Features présente en association avec Axon Films Une production Groundswell/Jinks/Cohen Company un film de GUS VAN SANT SEAN PENN HARVEY MILK EMILE HIRSCH JOSH BROLIN DIEGO LUNA et JAMES FRANCO Durée : 2h07 SORTIE NATIONALE LE 4 MARS 2008 Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.snd-films.com DISTRIBUTION : RELATIONS PRESSE : SND JEAN-PIERRE VINCENT 89, avenue Charles-de-Gaulle SOPHIE SALEYRON 92575 Neuilly-sur-Seine Cedex 12, rue Paul Baudry Tél. : 01 41 92 79 39/41/42 75008 Paris Fax : 01 41 92 79 07 Tél. : 01 42 25 23 80 3 SYNOPSIS Le film retrace les huit dernières années de la vie d’Harvey Milk (SEAN PENN). Dans les années 1970 il fut le premier homme politique américain ouvertement gay à être élu à des fonctions officielles, à San Francisco en Californie. Son combat pour la tolérance et l’intégration des communautés homosexuelles lui coûta la vie. Son action a changé les mentalités, et son engagement a changé l’histoire. 5 CHRONOLOGIE 1930, 22 mai. Naissance d’Harvey Bernard Milk à Woodmere, dans l’Etat de New York. 1946 Milk entre dans l’équipe de football junior de Bay Shore High School, dans l’Etat de New York. 1947 Milk sort diplômé de Bay Shore High School. 1951 Milk obtient son diplôme de mathématiques de la State University (SUNY) d’Albany et entre dans l’U.S. Navy. 1955 Milk quitte la Navy avec les honneurs et devient professeur dans un lycée. 1963 Milk entame une nouvelle carrière au sein d’une firme d’investissements de Wall Street, Bache & Co. -

Harvey Milk Timeline

Harvey Milk Timeline • 1930: Harvey Bernard Milk is born. • 1947: Milk graduates high school. • 1950: __________________________________________ • 1951: Milk enlists in the Navy. • 1955: Milk is discharged from the Navy. • 1959: __________________________________________ • 1963: __________________________________________ • 1965: __________________________________________ • 1969: __________________________________________ • 1971: __________________________________________ • 1972: __________________________________________ • 1972: Milk moves from New York City to San Francisco. • 1973: Milk opens Castro Camera • 1973: Milk helps the Teamsters with their successful Coors boycott. • 1973: __________________________________________ • 1973: __________________________________________ • 1973: Milk runs for District 5 Supervisor for the first time and loses. • 1975: __________________________________________ • 1976: __________________________________________ • 1976: __________________________________________ • 1977: Milk is elected district Supervisor. • 1977: __________________________________________ • 1977: Milk led Milk led march against the Dade County Ordinance vote. • 1978: The San Francisco Gay Civil Rights Ordinance is signed. • 1978: __________________________________________ • 1978: Milk is assassinated by Dan White. • 1979: __________________________________________ • 1979: People protest Dan White’s sentence. This is known as the White Night. • 1981: __________________________________________ Add the following events into the timeline! -

Local Judges Opposie Regional Court Idea

Cloudy, Warm THEMLY Ctondy warm witt late show- era today. Cooler tonigit. Sun- } Red Bank, Freehold f FINAL ny, pleasant tomorrow and Long Branch / Thursday. EDITION Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 92 Years VOL 93 NO. 239 RED BANK, N.J., TUESDAY, JUNE 8,1971 TENCEWflJ A Vietnam Veteran: He's Not Bitter ByMABYBETHAlLEN Braille. he estimates that maybe eight were still against the Ger- skin of his teeth" from Mid- (Second of a series) Through operations to re- will ever, further their educa- mans and. the Japanese, and "dletowrr Township High tion or return to normalcy. he remembers being insulted LEONABDO-"Ican'tfeei move shrapnel and cataracts, School in 1966 and was "a big partial vision has been re- The .gripes, he says, come when he would go out in the surfing fanatic." He swam at mainly from patients in Army street. "I knew it might happen. .stored. Loss of his bands, he Edgewater Beach Club, Sea hospitals because "half of Fd worked .with explosives. I accepts without bitterness. "It got to the point," he Bright, and worked as a bus- them were drafted and didn't knew the chances of getting And he considers himself says, "where all I did was boy for Bahr's Restaurant, want to go in the first place." shot or blown up. There's not more fortunate than some of fight every day. So I blocked Highlands, because the hours "I've tried to sit down and much I could say about I'm the men whom he has seen in the German language out of fit his surfing schedule.