Extended Program Notes for Graduate Trumpet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Release Sheet

November 17, 2017 November 17, 2017 TALES OF TWO CITIES The Leipzig-Damascus Coffee House “powerful” “flawless” — The Globe and Mail — Musical Toronto Tafelmusik’s stunning multimedia concert Tales of Two Cities: The Leipzig-Damascus Coffee House is now available as a CD soundtrack and DVD that was filmed before a live audience at the Aga Khan Museum’s auditorium in Toronto. Inspired by the colourful, opulent world of 18th-century Saxon and Syrian coffee houses, Tales of Two Cities is performed entirely from memory by Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, ensemble Trio Arabica — Maryem Tollar, voice and qanun; Demetri Petsalakis, oud; and Naghmeh Farahmand, percussion — with narrator Alon Nashman. Described as an “enterprising concept … [that] blends elements that are entertaining, educational, musically rewarding and visually arresting” (Huffington Post Canada), Tales of Two Cities received rapturous critical acclaim at its May 2016 Toronto premiere and was named Best Concert of 2016 by the Spanish classical music magazine Codalario.com. DVD extras include subtitles in Arabic, a video on the restoration of the Dresden Damascus Room, behind-the-scenes footage from rehearsals, and a nine-camera split screen video of the orchestra performing Bach’s Sinfonia after BWV 248 in a new arrangement by Tafelmusik. TALES OF TWO CITIES The Leipzig-Damascus Coffee House DVD (Total Duration 1:37:15) CHAPTERS LISTING Chapter 1: Opening credits/Overture 5:41 Chapter 2: Coffee travels from the Middle East to Venice and Paris 15:57 Chapter 3: Coffee comes to Leipzig -

Tuba Syllabus / 2003 Edition

74058_TAP_SyllabusCovers_ART_Layout 1 2019-12-10 10:56 AM Page 36 Tuba SYLLABUS / 2003 EDITION SHIN SUGINO SHIN Message from the President The mission of The Royal Conservatory—to develop human potential through leadership in music and the arts—is based on the conviction that music and the arts are humanity’s greatest means to achieve personal growth and social cohesion. Since 1886 The Royal Conservatory has realized this mission by developing a structured system consisting of curriculum and assessment that fosters participation in music making and creative expression by millions of people. We believe that the curriculum at the core of our system is the finest in the world today. In order to ensure the quality, relevance, and effectiveness of our curriculum, we engage in an ongoing process of revitalization, which elicits the input of hundreds of leading teachers. The award-winning publications that support the use of the curriculum offer the widest selection of carefully selected and graded materials at all levels. Certificates and Diplomas from The Royal Conservatory of Music attained through examinations represent the gold standard in music education. The strength of the curriculum and assessment structure is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of outstanding musicians and teachers from Canada, the United States, and abroad who have been chosen for their experience, skill, and professionalism. An acclaimed adjudicator certification program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in helping all people to open critical windows for reflection, to unleash their creativity, and to make deeper connections with others. -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

HOWARD COLLEGE MUSIC FALL 2018 RECITAL Monday November 5, 2018 Hall Center for the Arts Linda Lindell, Accompanist

HOWARD COLLEGE MUSIC FALL 2018 RECITAL Monday November 5, 2018 Hall Center for the Arts Linda Lindell, Accompanist Makinsey Grant . Bb Clarinet Fantasy Piece No. 1 by Robert Schumann Fantasy Piece No. 1 by Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856) was written in 1849. It is the first movement of three pieces written to promote the creative notion of the performer. It allows the performer to be unrestricted with their imagination. Fantasy Piece No. 1 is written to be “Zart und mit Ausdruck” which translates to tenderly and expressively. It begins in the key of A minor to give the audience the sense of melancholy then ends in the key of A major to give resolution and leave the audience looking forward to the next movements. (M. Grant) Tony Lozano . Guitar Tu Lo Sai by Giuseppe Torelli (1650 – 1703) Tu lo sai (You Know It) This musical piece is emotionally fueled. Told from the perspective of someone who has confessed their love for someone only to find that they no longer feel the same way. The piece also ends on a sad note, when they find that they don’t feel the same way. “How much I do love you. Ah, cruel heart how well you know.” (T. Lozano) Ruth Sorenson . Mezzo Soprano Sure on this Shining Night by Samuel Barber Samuel Barber (1910 – 1981) was an American composer known for his choral, orchestral, and opera works. He was also well known for his adaptation of poetry into choral and vocal music. Considered to be one of the composers most famous pieces, “Sure on this shining night,” became one of the most frequently programmed songs in both the United States and Europe. -

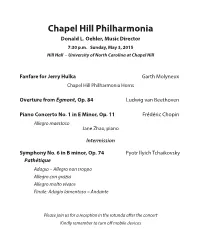

Concert Program

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

A Senior Recital

Senior Recitals Recitals 4-7-2008 A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Hansen, A. (2008). A Senior Recital. 1-1. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals/1 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Recitals by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. illi1YThe University Of Nevada Las Ve gas Co ll e~e of Fine Arts Ocparlmenl o f Music Pre:senls A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen, ptano ~Program~ ._a Conternplazione: Una Fantasia Piccola, Johann Nepomuk Hummel 1 Op. 107, No.3 (1778-1837) Deux Preludes Claude Achille Debussy Book 1, No.8: La fi/le aux cf7 eueux de /in (1862-1918) Book 2, No. 5: Bruyeres Ballades, Op. 10 Johannes Brahms No. 1 in D minor -Andante (1833-1897) No. 2 in D maj or -Andante No. 3 in B minor -Intermezzo No. 4 in B major - Andante con moto Papillons, Op. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. -

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

A New Species of Instrument: the Vented Trumpet in Context

1 A NEW SPECIES OF INSTRUMENT: THE VENTED TRUMPET IN CONTEXT Robert Barclay Introduction The natural trumpet is the one instrument not yet fully revived for use in the performance of Baroque music. A handful of recordings are available and very rarely a concert featuring solo performances on the instrument is given, but to a great extent the idiosyncrasies of the natural harmonic series are still considered to be beyond reliability in the recording studio or in live performance. Most current players have taken to using machine-made instruments with as many as four fi nger-holes placed in their tubing near to pressure nodes, so that the so-called “out-of-tune harmonics” of the natural series (principally f’/f#’, and a” ) will not be unpleasant to modern sensitivity. The vented instruments that have resulted from this recent “invention of tradition” are often equipped with so many anachronistic features that the result is a trumpet which resembles its Baroque counterpart only superfi cially, whose playing technique is quite different, and whose timbre is far removed from that expected for Baroque music. Among publications that deal with the compromises made to natural instruments in modern practice, those of Tim Collins, Richard Seraphinoff, and Crispian Steele-Perkins deserve especial mention. Collins provides an excellent summary of the characteristics of the natural trumpet, and an analysis of the current state of playing of the instrument.1 Seraphinoff concentrates on the early horn, and discusses the pros and cons of the use of vent holes in so-called historical performances.2 Steele-Perkins summarizes the develop- ment of the modern Baroque trumpet and provides practical advice on the selection of instruments3 All three authors highlight the tension that has arisen within the fi eld of early brass performance.