43540333.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

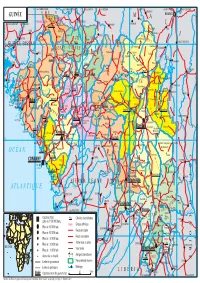

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (As of 17 Fev 2015)

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (as of 17 Fev 2015) Banian SENEGAL Albadariah Mamouroudou MALI Djimissala Kobala Centre GUINEA-BISSAU Mognoumadou Morifindou GUINEA Karala Sangardo Linko Sessè Baladou Hérémakono Tininkoro Sirana De Beyla Manfran Silakoro Samala Soromaya Gbodou Sokowoulendou Kabadou Kankoro Tanantou Kerouane Koffra Bokodou Togobala Centre Gbangbadou Koroukorono Korobikoro Koro Benbèya Centre Gbenkoro SIERRA LEONE Kobikoro Firawa Sassèdou Korokoro Frawanidou Sokourala Vassiadou Waro Samarami Worocia Bakokoro Boukorodou Kamala Fassousso Kissidougou Banankoro Bablaro Bagnala Sananko Sorola Famorodou Fermessadou Pompo Damaro Koumandou Samana Deila Diassodou Mangbala Nerewa LIBERIA Beindou Kalidou Fassianso Vaboudou Binemoridou Faïdou Yaradou Bonin Melikonbo Banama Thièwa DjénédouKivia Feredou Yombiro M'Balia Gonkoroma Kemosso Tombadou Bardou Gberékan Sabouya Tèrèdou Bokoni Bolnin Boninfé Soumanso Beindou Bondodou Sasadou Mama Koussankoro Filadou Gnagbèdou Douala Sincy Faréma Sogboro Kobiramadou Nyadou Tinah Sibiribaro Ouyé Allamadou Fouala Regional Capital Bolodou Béindou Touradala Koïko Daway Fodou 1 Dandou Baïdou 1 Kayla Kama Sagnola Dabadou Blassana Kamian Laye Kondiadou Tignèko Kovila Komende Kassadou Solomana Bengoua Poveni Malla Angola Sokodou Niansoumandou Diani District Capital Kokouma Nongoa Koïko Frandou Sinko Ferela Bolodou Famoîla Mandou Moya Koya Nafadji Domba Koberno Mano Kama Baïzéa Vassala Madina Sèmèkoura Bagbé Yendemillimo Kambadou Mohomè Foomè Sondou Diaboîdou Malondou Dabadou Otol Beindou Koindou -

IOM Guinea Ebola Response Situation Report, 8-31 March 2016

GUINEA EBOLA RESPONSE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION RAPPORT DE SITUATION From 8 to 31, March 2016 News Launching of the “soft ring containment” of Koropara sub-prefecture. © IOM Guinea 2016 On February 29 and March 17, three On March 9, 2016, IOM organized a From March 9 to 11, 2016, a joint IOM-RTI- people died in the sub-prefecture of ceremony during which, it officially handed- DPS mission went to different sub- Koropara following an unknown disease over the health post of Kamakouloun to sub- prefectures of Boffa for a maiden contact characterized by fever, deep emaciation, prefectural authorities of Kamsar, prefecture with local authorities. The aim was to explain diarrhea including vomiting of blood. A few of Boke. The health facility was rehabilitated the criteria used in the selection of CHA days later, two other people developed the and fully equipped by the organization. (Community Health Assistants), validating the same symptoms. The tests, carried out on list of CHA provided by the DPS in their March 17, were positive to the Ebola Virus localities and selecting 30 participants for the Disease, indicating the resurgence of the participatory mapping exercise (10 wise men, disease in Guinea, nearly three months after 10 youths and 10 women). it was officially declared over by WHO. Situation of the Ebola virus disease after its resurgence in Guinea In the sub-prefecture of Koropara, located at 97km from the city of NZerekore, an approximately 50-year-old farmer along with his two wives died between February 29 and March 17, 2016 following an unknown disease characterized by fever, deep emaciation, diarrhea and vomiting of blood. -

Guinea Ebola Response International Organization for Migration

GUINEA EBOLA RESPONSE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION RAPPORT DE SITUATION From 8 to 31, March 2016 News Launching of the “soft ring containment” of Koropara sub-prefecture. © IOM Guinea 2016 On February 29 and March 17, three On March 9, 2016, IOM organized a From March 9 to 11, 2016, a joint IOM-RTI- people died in the sub-prefecture of ceremony during which, it officially handed- DPS mission went to different sub- Koropara following an unknown disease over the health post of Kamakouloun to sub- prefectures of Boffa for a maiden contact characterized by fever, deep emaciation, prefectural authorities of Kamsar, prefecture with local authorities. The aim was to explain diarrhea including vomiting of blood. A few of Boke. The health facility was rehabilitated the criteria used in the selection of CHA days later, two other people developed the and fully equipped by the organization. (Community Health Assistants), validating the same symptoms. The tests, carried out on list of CHA provided by the DPS in their March 17, were positive to the Ebola Virus localities and selecting 30 participants for the Disease, indicating the resurgence of the participatory mapping exercise (10 wise men, disease in Guinea, nearly three months after 10 youths and 10 women). it was officially declared over by WHO. Situation of the Ebola virus disease after its resurgence in Guinea In the sub-prefecture of Koropara, located at 97km from the city of NZerekore, an approximately 50-year-old farmer along with his two wives died between February 29 and March 17, 2016 following an unknown disease characterized by fever, deep emaciation, diarrhea and vomiting of blood. -

Plan De Gestion Environnementale Et Sociale (Pges)

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DE GUINEE ***************** TRAVAIL - JUSTICE – SOLIDARITE DIRECTION NATIONALE DU GENIE RURAL ***************** SECRETARIAT EXECUTIF DE L’ABN Public Disclosure Authorized PROJET DE DEVELOPPEMENT DES RESSOURCES EN EAU ET DE GESTION DURABLE DES ECOSYSTEMES DANS LE BASSIN DU NIGER (PDREGDE) ETUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL, EVALUATION SOCIALE ET EVENTUELS PLANS D’ACTION DE REINSTALLATION DANS LE CADRE DE L’APPUI AUX TRAVAUX D’AMENAGEMENTS HYDRO AGRICOLES, A LA RESTAURATION ET LE DEVELOPPEMENT DES ACTIVITES AGROFORESTERIES ET DE PROTECTION DES VERSANTS DANS LA REGION DE FARANAH, REPUBLIQUE DE LA GUINEE Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized FINANCEMENT IDA ETUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL VERSION PROVISOIRE CORRIGEE Public Disclosure Authorized Novembre 2013 SOCIETE D’ETUDES POLYTECHNIQUES Société à responsabilité limitée au capital de 1.500.000 F CFA BP: 3069 Bamako – N° Fiscal: 086 100086 V - Tél. : (+223) 20 20 69 29) SOMMAIRE ABREVIATIONS ET ACRONYMES.......................................................................................................... 5 LISTE DES TABLEAUX ET FIGURES ...................................................................................................... 6 RESUME ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... -

GUINÉE Gam L BAMAKO PARC NAT

14° vers TAMBACOUNDA vers TAMBACOUNDA 12° vers SARAYA vers KÉNÉBIA 10° vers KITA vers KITA 8° vers KOULIKORO vers SÉGOU S É N É G A L F SIRAKORO bie a GUINÉE Gam l BAMAKO PARC NAT. é M m A DU KONIAGUI é GALÉ FOULAKOUNDA BADIAR KÉDOUGOU g L n i B vers ZIGUINCHOR vers KOLDA F f SAGABARI a Youkounkoun ARABA a k Koundara o B y ba ï G Niagassola SIBI ê Sarébo do a G GABU Guingan m o T i b B Balandou I o i al K m T e F LÉ é R iba ouba A A M ok l i Kifaya Tamgué D A o vers BISSAO o L ro F Á K n 1538 m I BA AT Foulamôri é Balaki I Sou baraya N K A É OUÉLÉSSÉBOUGOU 12° GUINÉE-BISSAO Mali L Boukaria 12° B S m a O a Naboun Kouré alé n l y N E - G U I N É o o KANGABA k Y E N E N k a é XIME O a r M m Madina l Ya béring F a ÉL K andanda Maléa B u B I m n Koumbia Sala bandé Doko o Kounsitél É i a e Siguirini Barrage B bi g è è R al m in Diatif r E de Sélingué vers BISSAO ub Gaoual a f Rio Cor G a IG KANGARÉ BUBA oumb B Banora N é K a Koubia Nafadji n Kintinian é i i Dabalaré F m Malanta ô F o K llé ifa BOUGOUNI Wéndou Mbôrou T Ganiakali Siguiri n Fouta Labé T H Dialakoro o Lélouma ougué A g Tin vers SIKASSO o 1245 U kisso K Hamdallaï Kâkoni F L T E Kiniébakoura K O U A Dinguiraye - G Balandougouba CATIÓ LÉ o U I SANSA g Sélouma N É E o ê Dabiss H rico a Kalinko Koundianakoro n Missira Kankalabé Sangarédi m F YANFOLILA i Chutes arakoba Niandankoro r o e k de Kinkon ka s n Sansalé L A Santou a Pita s i ou i m Sansando c U K B k Ko ola Koura Niantanina a u F O Tén n ié M Niani BADOGO L C ing ilin m é i n GARA O T ta Konsota i T a O io Dobali Djalon B m -

Guinea Nutrition Assessment

Guinea Nutrition Assessment November 2015 ABOUT SPRING The Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project is a five-year USAID-funded cooperative agreement to strengthen global and country efforts to scale up high-impact nutrition practices and policies and improve maternal and child nutrition outcomes. The project is managed by JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc., with partners Helen Keller International, The Manoff Group, Save the Children, and the International Food Policy Research Institute. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS SPRING’s assessment team included Peggy Koniz-Booher, SPRING senior nutrition/SBCC advisor; Sarah Hogan, SPRING project coordinator; Susan van Keulen-Cantella, international agriculture consultant; Abdoul Khalighi Diallo, Guinean agriculture and food security consultant; Mohamed Lamine Fofana, Guinean nutrition advisor (Helen Keller International [HKI]); and Ibrahim Yansane, chief of the extension services, Guinean Ministry of Agriculture (MOA). While conducting field visits, SPRING partnered with field staff from two local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Kissisdougou (APARFE) and in Faranah (Tostan), with special thanks to Keloua Ouendouno and Michel Tolno from APARFE, and Ansoumane Diawara and Ibrahima Toure from Tostan. HKI, SPRING’s global partner with offices in Guinea, was key in providing logistical and context support throughout the assessment. Several SPRING headquarters staff were also key contributors to the assessment, specifically Heather Danton, Sascha Lamstein, -

GUINEA Ebola Situation Report

GUINEA Ebola Situation Report 9 December 2015 UNICEF A child in Conakry is vaccinated during the third round of the polio campaign HIGHLIGHTS SITUATION IN NUMBERS As of 6 December 2015 As of 6 December 2015, Guinea had reached Day 20 of the 42-day countdown to the Ebola outbreak being declared over. There 3,804 have been no new cases of Ebola now for 38 days, keeping the Cases of Ebola (3,351 total tally of confirmed cases at 3,351. confirmed) From 5 to 8 December 2015, UNICEF supported the Ministry of Health in organizing the third round of the latest polio vaccination 2,536 campaign, targeting 2,189,521 children in 38 health districts. In Deaths (2,083 confirmed) addition to being vaccinated, all children aged 6 to 59 months received treatment for worms and vitamin A supplementation. 749 Cases among children 0-17 In the past two weeks, cash transfers were made to 37 parents (confirmed) and caretakers of 157 children (72 girls) who have lost one or both parents due to Ebola in Forécariah. The total number of orphaned 519 children provided with cash transfers is 5,781 out of 6,220 Deaths of children and youth registered children. aged 0-17 (confirmed) Activities to monitor schools after they reopened for the new 4,350,633 academic year on 9 November 2015 – particularly checking for Children in affected areas since the physical presence of teachers – are drawing to a close. the beginning of the epidemic Reports are being prepared and their contents will be duly analyzed. -

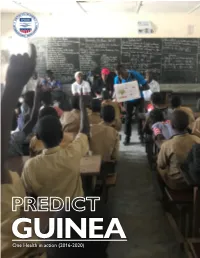

GUINEA One Health in Action (2016-2020) Lessons Learned from Ebola GUINEA EBOLA HOST PROJECT

GUINEA One Health in action (2016-2020) Lessons learned from Ebola GUINEA EBOLA HOST PROJECT Guinea, a country of approximately interface, as well as significant challenges source of Ebola and other devastating 12.9 million people on the Atlantic for disease prevention and control. filoviruses, and to investigate human coast of West Africa, is characterized behaviors associated with virus In 2013, somewhere in the Forest by several different climatic zones, spillover. Region of Guinea, one of these largely due to great geographic diversity. spillover events presumably sparked In Guinea, the PREDICT project’s There are more than 1,300 rivers in by human contact with an infected primary goal was to identify the wildlife the country. Many major rivers, such bat, spread across the Guinea-Sierra hosts of Ebola virus, investigate the as Niger, Senegal (Bafing), The Gambia, Leone-Liberia border region and grew distribution of the virus, and assess and as well as their main tributaries have into the largest Ebola virus epidemic characterize risks for future spillover their sources in Guinea, making this in history, leaving over 28,000 people and emergence. In partnership with country the “Water Tower” of West infected and more than 11,000 dead, the Government of Guinea, PREDICT Africa. Guinea has the largest reserves with 2,544 deaths in Guinea alone. also strengthened health security by of bauxite in the world and the largest This outbreak had devastating impacts supporting improvements in national untapped reserves of iron ore, gold on Guinea’s economy and health capacity for wildlife disease surveillance and diamonds. Despite its significant infrastructure and dramatically affected and bolstering disease detection natural resource potential, the Guinean the livelihoods of Guineans. -

ULU W Fl FEB20 FACSIMILE MESSAGE GENERAL To: Destination Fax Number: Mr

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT IGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES Case Posiale 25OO CH-1211 Geneve 2 Depot ULU W fl FEB20 FACSIMILE MESSAGE GENERAL To: Destination fax number: Mr. S. Iqbat Riza 001.212.963.3826 Chef de Cabinet Executive Office of the Secretary-General From: Return fax number: 739.7346 Ruud Lubbers 7e// (022) 739.8254 Email: saunderm@unhcr,ch Date: 2O February 2OO1 No. of pages including this page: 7O File code: hem Subject: Letter to the Secretary-General I would be grateful if you could share the attached with the Secretary-General: 1. Letter to the Secretary-General 2. Draft letter to the President of the Security Council 3. Letter to the former President of the Security Council (Ambassador Mahbubani of Singapore) 4. Relation between UNHCR's plan on Safe Access etc, and ECOWAS 5. Action Plan on RUF. I look forward to receiving the Secretary-General's comments. Best regards. HSIH-HDHNII Ci 6CZ ZZ If XVd CT>:?T ffill TO, ZQ/OZ NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS LEHAUT COMM1SSA1RE THE HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LE5 FOR REFUGEES Case Ftestato 2500 CH-1211 Genovo 2 Dcpfil Suisse 19 February 2001 EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL Pear Mr. Secretary-General, _Ypu win find herewith enclosed a draft of my letter to the President of the Security Council. I could, of course, also communicate this information to the Security Council in a different form such as a report should you prefer. The President of the Security Council asked me to come and brief the Security Council and answer questions. -

Guinea: Reference Map of Guéckédou Prefecture (As of 27 Fev 2015)

Guinea: Reference Map of Guéckédou Prefecture (as of 27 Fev 2015) Taiandu Sankarama Beindou Kolakoya Simafereya SENEGAL Niriyifeh Yombiro MALI Sumaworia Fakondeya I Bendu I Sondayou Sendiya Mondeia Manson Banama GUINEA-BISSAU Tambaia Yarandor Korodiyakoro Keama Yandakoro Bonin Bonin Wondodou Tarwortor I Tilekoro Nerekoro Saldou Bula-warafia Yerawadu TEMESSADOU CENTRE Kuleror Yiria Böönin Bardou Buru-Fasenia DEC Primary School Yarawadu Polytho GUINEA Tawortor II Konkowakoro Yediobengou 1 Konkowakoro Konin Kulia (B) DEC Primary School Konkonia Kondewakor Yediobengou 2 Mama Parc Kulia (A) Fayeya Durukoro Poteya Sayama Faréma Duwulemma Totor Kombodu Folakoro COTE D'IVOIRE Gbolia Sinsin Beindou Ouedou Musaia Fakondeya II Bendu Gbanworoya Kamaradu Samadou Kundema I KOUNTE CENTRE Kundema II Wasaya Dandu Bolodou Bawadu Fosiotyo SIERRA LEONE Yarakonko Dandu Makongodu Sandia Sowadu Sindakoro Frandala Koïko Frawandou Kissi Sukurella Kamindo Dawayi Kenema Yogboma Nelikoro II Bakandor Popor Kongradiya Sonfondu Salékoudou Maledou Sianfran Kpetema Kawian Dolaro Kouaro Bendu Bolodu YOMADOU CENTRE Kama MCA Primary School Sarandou Beindou Yengema Yendio-Bengu Gbilinba Dandou Kemodu Kamian Sambaia Yombidou LIBERIA Pengidu Kurumbaya Dakadou Chimandu Fosayma Gbikidala Bumbeh Komende Sofédou OULAKO Kassadou Faindu Kankankoura Gbondou Badala Tiessainaye Faréma Baladou Bongo Badala Hermakono Angola Kwakoima Wasaya Teidu Gbandu Soyadou Ouende Kondiadou Kokouma Bandadou Nongoa FARAWANDOU CENTRE SIERRA LEONE Health Centre Kunundu Wangai TOUMANDOU CENTRE Dembadou -

Citizens' Involvement in Health Governance

CITIZENS’ INVOLVEMENT IN HEALTH GOVERNANCE (CIHG) Endline Data Collection Final Report September 2020 This report was prepared with funds provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development under Cooperative Agreement AID-675-LA-17-00001. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development. Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................... 1 I. Introduction ............................................................................................... 5 Overview ...................................................................................................... 5 Background................................................................................................... 5 II. Methodology ............................................................................................ 6 Approach ...................................................................................................... 6 Data Collection ............................................................................................. 7 Analysis ....................................................................................................... 10 Limitations .................................................................................................. 10 Safety and Security ..................................................................................... 11 III. Findings ................................................................................................ -

SCS Guinea: Citizen Involvement in Health Governance

SCS Guinea: Citizen Involvement in Health Governance Funding provided by: United States Agency for International Development Cooperative Agreement No. AID-675-LA-17-00001 Baseline Assessment: Submitted: January 19, 2018 Washington, DC Submitted to: Ruben Johnson Agreement Officer Representative USAID/Guinea [email protected] This report was prepared with funds provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development under Cooperative Agreement AID-675-LA-17-00001. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development. CONTENTS ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................................. ii I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Citizens’ Involvement in Health Governance Activity .......................................................... 3 2.2 Guinea Background ............................................................................................................... 4 III. ASSESSMENT PURPOSE AND QUESTIONS .............................................................. 12 IV. BASELINE ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY.............................................................. 13 4.1 Nationwide Household Opinion Survey ............................................................................