Azerbaijan by H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elections, Democratization, and Human Rights in Azerbaijan

ELECTIONS, DEMOCRATIZATION, AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN AZERBAIJAN HEARING BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MAY 25, 2000 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe [CSCE 106-2-10] Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.csce.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2001 67-554PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: (202) 5121800 Fax: (202) 5122250 Mail Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 204020001 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS HOUSE SENATE CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado Chairman Co-Chairman FRANK R. WOLF, Virginia KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas MATT SALMON, Arizona SPENCER ABRAHAM, Michigan JAMES C. GREENWOOD, Pennsylvania SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania TIM HUTCHINSON, Arkansas STENY H. HOYER, Maryland FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland BOB GRAHAM, Florida LOUISE McINTOSH SLAUGHTER, New York RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin MICHAEL P. FORBES, New York CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS HAROLD HONGJU KOH, Department of State EDWARD L. WARNER III, Department of Defense PATRICK A. MULLOY, Department of Commerce COMMISSION S TAFF DOROTHY DOUGLAS TAFT, Chief of Staff RONALD J. MCNAMARA, Deputy Chief of Staff BEN ANDERSON, Communications Director ELIZABETH M. CAMPBELL, Office Administrator OREST DEYCHAKIWSKY, Staff Advisor JOHN F. FINERTY, Staff Advisor CHADWICK R. GORE, Staff Advisor ROBERT HAND, Staff Advisor JANICE HELWIG, Staff Advisor MARLENE KAUFMANN, Counsel KAREN S. LORD, Counsel for Freedom of Religion MICHELE MADASZ, Staff Assistant/Systems Administrator MICHAEL J. -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Spotlight on Azerbaijan

Spotlight on azerbaijan provides an in-depth but accessible analysis of the major challenges Azerbaijan faces regarding democratic development, rule of law, media freedom, property rights and a number of other key governance and human rights issues while examining the impact of its international relationships, the economy and the unresolved nagorno-Karabakh conflict on the domestic situation. it argues that UK, EU and Western engagement in Azerbaijan needs to go beyond energy diplomacy but that increased engagement must be matched by stronger pressure for reform. Edited by Adam hug (Foreign policy Centre) Spotlight on Azerbaijan contains contributions from leading Azerbaijan experts including: Vugar Bayramov (Centre for Economic and Social Development), Michelle Brady (American Bar Association Rule of law initiative), giorgi gogia (human Rights Watch), Vugar gojayev (human Rights house-Azerbaijan) , Jacqueline hale (oSi-EU), Rashid hajili (Media Rights institute), tabib huseynov, Monica Martinez (oSCE), Dr Katy pearce (University of Washington), Firdevs Robinson (FpC) and Denis Sammut (linKS). The Foreign Policy Centre Spotlight on Suite 11, Second floor 23-28 Penn Street London N1 5DL United Kingdom www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] aZERBaIJaN © Foreign Policy Centre 2011 Edited by adam Hug all rights reserved ISBN-13 978-1-905833-24-5 ISBN-10 1-905833-24-5 £4.95 Spotlight on Azerbaijan Edited by Adam Hug First published in May 2012 by The Foreign Policy Centre Suite 11, Second Floor, 23-28 Penn Street London N1 5DL www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] © Foreign Policy Centre 2012 All Rights Reserved ISBN 13: 978-1-905833-24-5 ISBN 10: 1-905833-24-5 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foreign Policy Centre. -

Elemental Composition, Leachability Assessment and Spatial Variability Analysis Of

https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-2019-66 Preprint. Discussion started: 4 November 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Article Type: Original Research 2 3 4 Elemental Composition, Leachability Assessment and Spatial Variability Analysis of 5 Surface Soils in the Mugan Plain in the Republic of Azerbaijan 6 7 Junho Han1, Zaman Mammadov2, Elton Mammadov2, Seoyeon Lee1, Jisuk Park1, 8 Garib Mammadov2, Guliyev Elovsat2, Hee-Myong Ro1* 9 10 1Department of Agricultural Biotechnology and Research Institute of Agriculture and Life 11 Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul, 08826, Republic of Korea 12 2Institute of Soil Science and Agro Chemistry, Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences, 13 Baku, AZ10073, Republic of Azerbaijan 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 *To whom correspondence should be addressed; 21 Hee-Myong Ro 22 Phone: 82-2-880-4645 23 Fax: 82-2-873-3122 24 Email: [email protected] 1 https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-2019-66 Preprint. Discussion started: 4 November 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. 25 Abstract 26 The Republic of Azerbaijan has suffered from low agricultural productivity caused by soil salinization and 27 erosion, and limited and insufficient soil data are available for economic and political reasons. In this study, soil 28 elemental composition and heavy metal levels were assessed by comparing the results of XRF and ICP-OES analyses 29 for the first time. Leachability assessment and spatial variability analysis were conducted to understand the soil 30 salinization properties, and 632 surface soil samples categorized as agricultural (Ag) or salt-affected (SA) soils from 31 the Mugan Plain were collected and analyzed. -

Human Rights Abuses in Azerbaijan

1 1 Human Rights House Network The Human Rights House Network (HRHN) is a community of human rights defenders working for more than 100 independent organisations operating in 16 Human Rights Houses in 13 countries. Empowering, supporting, and protecting human rights defenders, the Network members unite their voices to promote the universal freedoms of assembly, organisation, and expression, and the right to be a human rights defender. The Secretariat, the Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF) based in Oslo, with offices in Geneva and Brussels, stewards the community, raising awareness internationally, raising concerns at the Council of Europe, the European Union and the United Nations, and other international institutions, and coordinating best use and sharing of the knowledge, expertise, influence, and resources within HRHN. Contact persons for the report: Alexander Sjödin European Advocacy Officer, Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF) Email: [email protected] Tel: +32 49 78 15 918 Florian Irminger Head of Advocacy, Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF) Email: [email protected] Tel: +41 79 751 80 42 Oslo office Menneskerettighetshuset Kirkegata 5, 0153 Oslo (Norway) Geneva office Rue de Varembé 1 (5th floor) PO Box 35, 1211 Geneva 20 (Switzerland) Brussels office Rue de Trèves 45, 1040 Brussels (Belgium) 2 For human rights defenders in Azerbaijan In June 2014, a number of Azerbaijani human rights defenders, including Emin Huseynov, Rasul Jafarov, and Intigam Aliyev organised a side-event in Strasbourg when President Aliyev addressed the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). Two months later, Rasul Jafarov and Intigam Aliyev were arrested, and shortly thereafter Emin Huseynov fled to the Swiss Embassy in Baku for protection against his own impending arrest. -

Azerbaijan | Freedom House

Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan About Us DONATE Blog Mobile App Contact Us Mexico Website (in Spanish) REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Subscribe Donate NATIONS IN TRANSIT - View another year - ShareShareShareShareShareMore 7 Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Nations in Transit 2014 DRAFT REPORT 2014 SCORES PDF version Capital: Baku 6.68 Population: 9.3 million REGIME CLASSIFICATION GNI/capita, PPP: US$9,410 Consolidated Source: The data above are drawn from The World Bank, Authoritarian World Development Indicators 2014. Regime 6.75 7.00 6.50 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.75 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: 1 of 23 6/25/2014 11:26 AM Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan Azerbaijan is ruled by an authoritarian regime characterized by intolerance for dissent and disregard for civil liberties and political rights. When President Heydar Aliyev came to power in 1993, he secured a ceasefire in Azerbaijan’s war with Armenia and established relative domestic stability, but he also instituted a Soviet-style, vertical power system, based on patronage and the suppression of political dissent. Ilham Aliyev succeeded his father in 2003, continuing and intensifying the most repressive aspects of his father’s rule. -

Synergetics of the Language, National Consciousness and Culture by Globalization

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 5, No. 3; 2015 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Synergetics of the Language, National Consciousness and Culture by Globalization Nigar Chingiz Veliyeva1 1 Azerbaijan University of Languages, Baku, Azerbaijan Correspondences: Nigar Chingiz Veliyeva, Azerbaijan University of Languages, Baku, Azerbaijan. E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 15, 2015 Accepted: April 10, 2015 Online Published: May 30, 2015 doi:10.5539/ijel.v5n3p154 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v5n3p154 Abstract The main aim of the investigation is to learn out all positive and negative influences of the process of globalization on the formation and development of the national language, national consciousness and national culture in the modern world during the intercultural communication and to analyze the power and impact of the Modern English as a global language to our national Azerbaijani language. To study such a global problem from the different view points as of native, so foreign scientists is also one of the main aims. The process of globalization, covering various spheres of life, is universal, as for thousands of years separated, remote to some extent, differential events—national or regional peculiarities, habits, complexes strongly influenced by modern technologies, approaching each other with incredible speed and combine as a result of multifaceted economic, socio-political, moral and ideological ties, limiting the kind of peculiarities, lead to the events and processes happening in the world. It is obvious that there is a great influence on the language’s enrichment of the process of globalization, which had taken place in the world. -

Review Article

Ashdin Publishing Journal of Drug and Alcohol Research Vol. 10 (2021), Article ID 23612, 04 pages Review Article Relno Situation Foreign Economic Relations and Geopolitical Perspective Azerbaijan Z.H.Aliyev*1 Dr.D.I.Allaxverdiyev2 1Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Address Correspondence to: ZH Aliyev, Professor, Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan; E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 11, 2021; Accepted: April 25, 2021; Published: May 4, 2021 Copyright: © 2021 Aliyev. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract “natural resources, ill-conceived, irrational and ill-use, op- The purpose of research is to identify the prospects for foreign economic eration as a result of their destruction, leading the world to relations and sustainable development of the geopolitical interests of the destruction leads and so prosperous development our econ- world, an increase in foreign investment, the development of competitive omy, and is the cause of sustainable artımaına exposure national wealth, disclosure and recreate the real picture of foreign eco- nomic relations. Given the increase in the rate of development of diplo- over time, adverse effects on future generations, “he said. matic and economic relations between the countries of the world deter- mines the need for the creation of new forms of foreign economic relations Theodore Roosevelt approach to the controversial event in of Azerbaijan. -

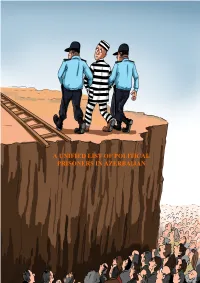

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

Parliamentary Program of Azerbaijan Evaluation, DI

AZERBAIJANN PARLIAMENTARY PROGRAM OF AZERBAIJAN EVALUATION FINAL REPORT JULY 2011 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Democracy International, Inc. DISCLAIMER This is an external evaluation. The views expressed in this document are the authors' and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development by Democracy International, Inc., through Task Order No. AID-112-TO-11-00002 under the Analytical Services II Indefinite Quantity Contract (USAID Contract No. AID-OAA-I-10- 00004). Team: • Lincoln Mitchell, Ph.D. • Rashad Shirinov, M.A. Democracy International: Democracy International, Inc. 4802 Montgomery Lane Bethesda, MD 20814 Tel: 301-961-1660 www.democracyinternational.com PARLIAMENTARY PROGRAM OF AZERBAIJAN EVALUATION FINAL REPORT JULY 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................. III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................... V 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY .................................................. 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ........................................................... 1 1.2 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 2.0 PROGRAM BACKGROUND ................................................................... -

Committee of Ministers Secrétariat Du Comité Des Ministres

SECRETARIAT / SECRÉTARIAT SECRETARIAT OF THE COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS SECRÉTARIAT DU COMITÉ DES MINISTRES Contact: John Darcy Tel: 03 88 41 31 56 Date: 07/11/2019 DH-DD(2019)1295 Document distributed under the sole responsibility of its author, without prejudice to the legal or political position of the Committee of Ministers. Meeting: 1362nd meeting (December 2019) (DH) Communication from a NGO (E.M.D.S: Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Centre) (22/10/2019) in the Namat Aliyev group of cases v. Azerbaijan) (Application No. 18705/06) Information made available under Rule 9.2 of the Rules of the Committee of Ministers for the supervision of the execution of judgments and of the terms of friendly settlements. * * * * * * * * * * * Document distribué sous la seule responsabilité de son auteur, sans préjuger de la position juridique ou politique du Comité des Ministres. Réunion : 1362e réunion (décembre 2019) (DH) Communication d’une ONG (E.M.D.S: Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Centre) (22/10/2019) dans le groupe d’affaires Namat Aliyev c. Azerbaïdjan (requête n° 18705/06) (anglais uniquement). Informations mises à disposition en vertu de la Règle 9.2 des Règles du Comité des Ministres pour la surveillance de l’exécution des arrêts et des termes des règlements amiables. DH-DD(2019)1295: Rule 9.2 Communication from a NGO in Namat Aliyev v. Azerbaijan. Document distributed under the sole responsibility of its author, without prejudice to the legal or political position of the Committee of Ministers. DGI 22 OCT. 2019 SERVICE DE L’EXECUTION DES ARRETS DE LA CEDH 22 October 2019 Head of the Department of Execution of Judgments Directorate of Monitoring Council of Europe Avenue de l’Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex France Namat Aliyev v. -

Azerbaijan: Downward Spiral: Continuing Crackdown on Freedoms in Azerbaijan

DOWNWARD SPIRAL: CONTINUING CRACKDOWN ON FREEDOMS IN AZERBAIJAN Amnesty International Publications First published in 2013 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2013 Index: EUR 55/010/2013 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. CONTENTS 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 2. Shrinking space for free media ................................................................................... 7 2.1 The continuing use of defamation suits to silence government critics ........................ 7 2.2 State control of broadcast media ........................................................................... 8 2.3 Harassment, intimidation and imprisonment of journalists ......................................