Juanita Jackson Mitchell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kweisi Mfume 1948–

FORMER MEMBERS H 1971–2007 ������������������������������������������������������������������������ Kweisi Mfume 1948– UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE H 1987–1996 DEMOCRAT FROM MARYLAND n epiphany in his mid-20s called Frizzell Gray away stress and frustration, Gray quit his jobs. He hung out A from the streets of Baltimore and into politics under on street corners, participated in illegal gambling, joined a new name: Kweisi Mfume, which means “conquering a gang, and fathered five sons (Ronald, Donald, Kevin, son of kings” in a West African dialect. “Frizzell Gray had Keith, and Michael) with four different women. In the lived and died. From his spirit was born a new person,” summer of 1972, Gray saw a vision of his mother’s face, Mfume later wrote.1 An admirer of civil rights leader Dr. convincing him to leave his life on the streets.5 Earning Martin Luther King, Jr., Mfume followed in his footsteps, a high school equivalency degree, Gray changed his becoming a well-known voice on Baltimore-area radio, the name to symbolize his transformation. He adopted the chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), and name Kweisi Mfume at the suggestion of an aunt who the leader of one of the country’s oldest advocacy groups had traveled through Ghana. An earlier encounter with for African Americans, the National Association for the future Baltimore-area Representative Parren Mitchell, who Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). challenged Mfume to help solve the problems of poverty Kweisi Mfume, formerly named Frizzell Gray, was and violence, profoundly affected the troubled young born on October 24, 1948, in Turners Station, Maryland, man.6 “I can’t explain it, but a feeling just came over me a small town 10 miles south of Baltimore. -

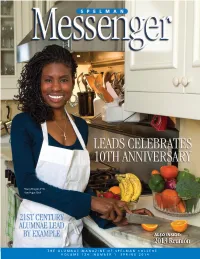

SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger

Stacey Dougan, C’98, Raw Vegan Chef ALSO INSIDE: 2013 Reunion THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE VOLUME 124 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Jo Moore Stewart Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs ASSOCIATE EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Joyce Davis Atlanta, GA 30314 COPY EDITOR OR Janet M. Barstow [email protected] Submission Deadlines: GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Spring Semester: January 1 – May 31 Fall Semester: June 1 – December 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER ALUMNAE NOTES Alyson Dorsey, C’2002 Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE • Education Eloise A. Alexis, C’86 • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Tomika DePriest, C’89 • Professional Kassandra Kimbriel Jolley Please include the date of the event in your Sharon E. Owens, C’76 submission. TAKE NOTE! WRITERS S.A. Reid Take Note! is dedicated to the following Lorraine Robertson alumnae achievements: TaRessa Stovall • Published Angela Brown Terrell • Appearing in films, television or on stage • Special awards, recognition and appointments PHOTOGRAPHERS Please include the date of the event in your J.D. Scott submission. Spelman Archives Julie Yarbrough, C’91 BOOK NOTES Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae authors. Please submit review copies. The Spelman Messenger is published twice a year IN MEMORIAM by Spelman College, 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive Atlanta, Georgia 30314-4399, free of charge notice of the death of a Spelman sister, please for alumnae, donors, trustees and friends of contact the Office of Alumnae Affairs at the College. -

Jew Taboo: Jewish Difference and the Affirmative Action Debate

The Jew Taboo: Jewish Difference and the Affirmative Action Debate DEBORAH C. MALAMUD* One of the most important questions for a serious debate on affirmative action is why certain minority groups need affirmative action while others have succeeded without it. The question is rarely asked, however, because the comparisonthat most frequently comes to mind-i.e., blacks and Jews-is seen by many as taboo. Daniel A. Farberand Suzanna Sherry have breached that taboo in recent writings. ProfessorMalamud's Article draws on work in the Jewish Studies field to respond to Farberand Sherry. It begins by critiquing their claim that Jewish values account for Jewish success. It then explores and embraces alternative explanations-some of which Farberand Sheny reject as anti-Semitic-as essentialparts of the story ofJewish success in America. 1 Jews arepeople who are not what anti-Semitessay they are. Jean-Paul Sartre ha[s] written that for Jews authenticity means not to deny what in fact they are. Yes, but it also means not to claim more than one has a right to.2 Defenders of affirmative action today are publicly faced with questions once thought improper in polite company. For Jewish liberals, the most disturbing question on the list is that posed by the comparison between the twentieth-century Jewish and African-American experiences in the United States. It goes something like this: The Jews succeeded in America without affirmative action. In fact, the Jews have done better on any reasonable measure of economic and educational achievement than members of the dominant majority, and began to succeed even while they were still being discriminated against by this country's elite institutions. -

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF Mourns the Loss of the Honora

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF mourns the loss of The Honorable John Lewis, an esteemed member of Congress and revered civil rights icon with whom our organization has a deeply personal history. Mr. Lewis passed away on July 17, 2020, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old. “I don’t know of another leader in this country with the moral standing of Rep. John Lewis. His life and work helped shape the best of our national identity,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s President & Director-Counsel. “We revered him not only for his work and sacrifices during the Civil Rights Movement, but because of his unending, stubborn, brilliant determination to press for justice and equality in this country. “There was no cynicism in John Lewis; no hint of despair even in the darkest moments. Instead, he showed up relentlessly with commitment and determination - but also love, and joy and unwavering dedication to the principles of non-violence. He spoke up and sat-in and stood on the front lines – and risked it all. This country – every single person in this country – owes a debt of gratitude to John Lewis that we can only begin to repay by following his demand that we do more as citizens. That we ‘get in the way.’ That we ‘speak out when we see injustice’ and that we keep our ‘eyes on the prize.’” The son of sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. He grew up attending segregated public schools in the state’s Pike County and, as a boy, was inspired by the work of civil rights activists, including Dr. -

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillm

“A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By: Thomas Anthony Gass, M.A. Department of History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Advisor Dr. Kevin Boyle Dr. Curtis Austin 1 Copyright by Thomas Anthony Gass 2014 2 Abstract “A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975” traces the history and activities of the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from its revitalization during the Great Depression to the end of the Black Power Movement. The dissertation examines the NAACP’s efforts to eliminate racial discrimination and segregation in a city and state that was “neither North nor South” while carrying out the national directives of the parent body. In doing so, its ideas, tactics, strategies, and methods influenced the growth of the national civil rights movement. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the Jackson, Mitchell, and Murphy families and the countless number of African Americans and their white allies throughout Baltimore and Maryland that strove to make “The Free State” live up to its moniker. It is also dedicated to family members who have passed on but left their mark on this work and myself. They are my grandparents, Lucious and Mattie Gass, Barbara Johns Powell, William “Billy” Spencer, and Cynthia L. “Bunny” Jones. This victory is theirs as well. iii Acknowledgements This dissertation has certainly been a long time coming. -

Working the Democracy: the Long Fight for the Ballot from Ida to Stacey

Social Education 84(4), p. 214–218 ©2020 National Council for the Social Studies Working the Democracy: The Long Fight for the Ballot from Ida to Stacey Jennifer Sdunzik and Chrystal S. Johnson After a 72-year struggle, the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted whose interests should be represented, American women the right to vote in 1920. Coupled with the Fifteenth Amendment, and ultimately what policies will be which extended voting rights to African American men, the ratification of the implemented at the local and national Nineteenth Amendment transformed the power and potency of the American electorate. levels. At a quick glance, childhoods par- Yet for those on the periphery—be Given the dearth of Black women’s tially spent in Mississippi might be the they people of color, women, the poor, voices in the historical memory of the only common denominator of these two and working class—the quest to exer- long civil rights struggle, we explore the women, as they were born in drastically cise civic rights through the ballot box stories of two African American women different times and seemed to fight dras- has remained contested to this day. In who harnessed the discourse of democ- tically different battles. Whereas Wells- the late nineteenth century and into the racy and patriotism to argue for equality Barnett is best known for her crusade twentieth, white fear of a new electorate and justice. Both women formed coali- against lynchings in the South and her of formerly enslaved Black men spurred tions that challenged the patriarchal work in documenting the racial vio- public officials to implement policies boundaries limiting who can be elected, lence of the 1890s in publications such that essentially nullified the Fifteenth as Southern Horrors and A Red Record,1 Amendment for African Americans in she was also instrumental in paving the the South. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced one individual views toward women of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 25, Number 20, May 15, 1998

EIR Founder and Contributing Editor: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. Editorial Board: Melvin Klenetsky, Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., Antony Papert, Gerald Rose, From the Associate Editor Dennis Small, Edward Spannaus, Nancy Spannaus, Jeffrey Steinberg, William Wertz Associate Editor: Susan Welsh Managing Editors: John Sigerson, ith this issue of EIR, the LaRouche movement is launching a Ronald Kokinda W Science Editor: Marjorie Mazel Hecht new strategic initiative to secure Lyndon LaRouche’s exoneration. Special Projects: Mark Burdman As our Feature emphasizes, the fate of the Clinton Presidency, and Book Editor: Katherine Notley Advertising Director: Marsha Freeman the prospects for restoring the rule of natural law, depend, more than Circulation Manager: Stanley Ezrol ever, on the exoneration of LaRouche. This point is further under- INTELLIGENCE DIRECTORS: scored by Edward Spannaus’s article in the National section, which Asia and Africa: Linda de Hoyos Counterintelligence: Jeffrey Steinberg, documents the fact that Clinton’s enemies are the same as Paul Goldstein LaRouche’s enemies (in this case, former U.S. Attorney Henry Hud- Economics: Marcia Merry Baker, William Engdahl son, the prosecutor who jailed LaRouche and is now publicly boost- History: Anton Chaitkin ing Kenneth Starr’s efforts to do the same thing to the President). Ibero-America: Robyn Quijano, Dennis Small Law: Edward Spannaus Between now and Memorial Day, we shall organize an intense Russia and Eastern Europe: lobbying effort on Capitol Hill, including a top-level delegation of Rachel Douglas, Konstantin George United States: Debra Freeman, Suzanne Rose signers of the petition to the President calling for LaRouche’s exoner- INTERNATIONAL BUREAUS: ation. -

ELLA BAKER, “ADDRESS at the HATTIESBURG FREEDOM DAY RALLY” (21 January 1964)

Voices of Democracy 11 (2016): 25-43 Orth 25 ELLA BAKER, “ADDRESS AT THE HATTIESBURG FREEDOM DAY RALLY” (21 January 1964) Nikki Orth The Pennsylvania State University Abstract: Ella Baker’s 1964 address in Hattiesburg reflected her approach to activism. In this speech, Baker emphasized that acquiring rights was not enough. Instead, she asserted that a comprehensive and lived experience of freedom was the ultimate goal. This essay examines how Baker broadened the very idea of “freedom” and how this expansive notion of freedom, alongside a more democratic approach to organizing, were necessary conditions for lasting social change that encompassed all humankind.1 Key Words: Ella Baker, civil rights movement, Mississippi, freedom, identity, rhetoric The storm clouds above Hattiesburg on January 21, 1964 presaged the social turbulence that was to follow the next day. During a mass meeting held on the eve of Freedom Day, an event staged to encourage African-Americans to vote, Ella Baker gave a speech reminding those in attendance of what was at stake on the following day: freedom itself. Although registering local African Americans was the goal of the event, Baker emphasized that voting rights were just part of the larger struggle against racial discrimination. Concentrating on voting rights or integration was not enough; instead, Baker sought a more sweeping social and political transformation. She was dedicated to fostering an activist identity among her listeners and aimed to inspire others to embrace the cause of freedom as an essential element of their identity and character. Baker’s approach to promoting civil rights activism represents a unique and instructive perspective on the rhetoric of that movement. -

Print ED381426.TIF (18 Pages)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 426 SO 024 676 AUTHOR Barnett, Elizabeth F. TITLE Mary McLeod Bethune: Feminist, Educator, and Social Activist. Draft. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the American Educational Research Association (New Orleans, LA, April 4-9, 1994). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Blacks; *Black Studies; Civil Rights; Cultural Pluralism; *Culture; *Diversity (Institutional); Females; *Feminism; Higher Education; *Multicultural Education; Secondary Education; *Women' Studies IDENTIFIERS *Bethune (Mary McLeod) ABSTRACT Multicultural education in the 1990s goes beyond the histories of particular ethnic and cultural groups to examine the context of oppression itself. The historical foundations of this modern conception of multicultural education are exemplified in the lives of African American women, whose stories are largely untold. Aspects of current theory and practice in curriculum transformation and multicultural education have roots in the activities of African American women. This paper discusses the life and contributions of Mary McLeod Bethune as an example of the interconnections among feminism, education, and social activism in early 20th century American life. (Author/EH) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made frt. the original doci'ment. ***************************A.****************************************** MARY MCLEOD BETHUNE: FEMINIST, EDUCATOR, AND SOCIAL ACTIVIST OS. 01411111111111T OP IMILICATION Pico of EdwoOomd Ill000s sod Idoomoome EDUCATIOOKL. RESOURCES ortaevAATION CENTEO WW1 Itfto docamm was MOO 4144116414 C111fteico O OM sown et ogimmio 0940411 4 OWV, Chanin him WWI IWO le MUM* 41014T Paris of lomat olomomosiedsito dew do rot 110011441104, .611.1181184 MON OEM 001140 01040/ Elizabeth F.