The Medieval Carol Genre: a Critical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

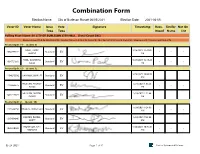

Combination Form

Combination Form Election Name: City of Burleson Runoff 06/05/2021 Election Date: 2021-06-05 Voter ID Voter Name Issue Vote Signature Timestamp Reas. Similar Not On Type Type Imped Name List Polling Place Name: EV CITY OF BURLESON CITY HALL (Total Count:245) Reason Imped (Y-0, N-245, Net-245) : Similar Name (Y-0, N-245, Net-245) : Not On List (Y-0, N-245, Net-245) : Standard-245, Provisional-0, Net-245 Precinct Split: 11- (Count: 2) POOL, LARRY 5/24/2021 12:45:02 1034793222 Standard EV - - - WAYNE PM POOL, DAVONNA 5/24/2021 12:45:28 1034721699 Standard EV - - - GAILE PM Precinct Split: 12- (Count: 3) 5/24/2021 10:08:30 1184023930 VAN NOY, JONI LEE Standard EV - - - AM MILBURN, AUDREY 5/24/2021 1:36:23 1146862575 Standard EV - - - RENEE PM MILBURN, DUSTIN 5/24/2021 2:51:44 1057217877 Standard EV - - - EVANS PM Precinct Split: 2- (Count: 14) 5/24/2021 9:24:06 1155522950 BASDEN, AMBER LEA Standard EV - - - AM BASDEN, DANIEL 5/24/2021 9:24:48 1215434046 Standard EV - - - SCOTT AM THOMPSON, KATI 5/24/2021 10:36:46 1050370989 Standard EV - - - MORGAN AM 05-24-2021 Page 1 of 21 Election Systems and Software Combination Form CRINER, JOAQUIN 5/24/2021 11:43:35 1052537873 Standard EV - - - RENE AM BOEDEKER, ALEXA 5/24/2021 11:45:30 1060105870 Standard EV - - - DANIELLE AM HOLMS, BARBARA 5/24/2021 11:59:40 1211090562 Standard EV - - - ANN AM HOLMS, BRADFORD 5/24/2021 12:00:52 1211090527 Standard EV - - - ANDREW PM 5/24/2021 12:33:18 2177469793 MABRY, ERIN NICOLE Standard EV - - - PM MABRY, TIMOTHY 5/24/2021 12:43:27 1200041381 Standard EV - - - -

2020-Commencement-Program.Pdf

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT 2020 Conferring of degrees at the close of the 144th academic year MAY 21, 2020 1 CONTENTS Degrees for Conferral .......................................................................... 3 University Motto and Ode ................................................................... 8 Awards ................................................................................................. 9 Honor Societies ................................................................................. 20 Student Honors ................................................................................. 25 Candidates for Degrees ..................................................................... 35 2 ConferringDegrees of Degrees for Conferral on Candidates CAREY BUSINESS SCHOOL Masters of Science Masters of Business Administration Graduate Certificates SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Doctors of Education Doctors of Philosophy Post-Master’s Certificates Masters of Science Masters of Education in the Health Professions Masters of Arts in Teaching Graduate Certificates Bachelors of Science PEABODY CONSERVATORY Doctors of Musical Arts Masters of Arts Masters of Audio Sciences Masters of Music Artist Diplomas Graduate Performance Diplomas Bachelors of Music SCHOOL OF NURSING Doctors of Nursing Practice Doctors of Philosophy Masters of Science in Nursing/Advanced Practice Masters of Science in Nursing/Entry into Nursing Practice SCHOOL OF NURSING AND BLOOMBERG SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH Masters of Science in Nursing/Masters of Public -

From the Black Death to Black Dance: Choreomania As Cultural Symptom

270 Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry, 8(2), pp 270–276 April 2021 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/pli.2020.46 From the Black Death to Black Dance: Choreomania as Cultural Symptom Ananya Jahanara Kabir Keywords: choreomania, imperial medievalism, Dionysian revivals, St. John’s dances, kola sanjon Paris in the interwar years was abuzz with Black dance and dancers. The stage was set since the First World War, when expatriate African Americans first began creating here, through their performance and patronage of jazz, “a new sense of black commu- nity, one based on positive affects and experience.”1 This community was a permeable one, where men and women of different races came together on the dance floor. As the novelist Michel Leiris recalls in his autobiographical work, L’Age d’homme, “During the years immediately following November 11th, 1918, nationalities were sufficiently con- fused and class barriers sufficiently lowered … for most parties given by young people to be strange mixtures where scions of the best families mixed with the dregs of the dance halls … In the period of great licence following the hostilities, jazz was a sign of allegiance, an orgiastic tribute to the colours of the moment. It functioned magically, and its means of influence can be compared to a kind of possession. -

Battlefieldbam

2016 BAM Next Wave Festival #BattlefieldBAM Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Battlefield BAM Harvey Theater Sep 28—30, Oct 1, 4—9 at 7:30pm Oct 1, 8 & 9 at 2pm; Oct 2 at 3pm Running time: approx. one hour & 10 minutes, no intermission C.I.C.T.—Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord Based on The Mahabharata and the play written by Jean-Claude Carrière Adapted and directed by Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne Music by Toshi Tsuchitori Costume design by Oria Puppo Lighting design by Phillippe Vialatte With Carole Karemera Jared McNeill Ery Nzaramba Sean O’Callaghan Season Sponsor: Major support for theater at BAM provided by: The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust Donald R. Mullen Jr. The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. Battlefield Photos: Simon Annand CAROLE KAREMERA JARED MCNEILL ERY NZARAMBA SEAN O’CALLAGHAN TOSHI TSUCHITORI Stage manager Thomas Becelewski American Stage Manager R. Michael Blanco The Actors are appearing with the permission of Actors’ Equity Association. The American Stage Manager is a member of Actors’ Equity Association. COPRODUCTION The Grotowski Institute; PARCO Co. Ltd / Tokyo; Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg; Young Vic Theatre / London; Singapore Repertory Theatre; Le Théâtre de Liège; C.I.R.T.; Attiki Cultural Society / Athens; Cercle des partenaires des Bouffes du Nord Battlefield DIRECTORS’ STATEMENT The Mahabharata is not simply a book, nor a great series of books, it is an immense canvas covering all the aspects of human existence. -

CRITTER LANE CHRONICLES the Summary of an Interesting Point

[Type a quote from the document or CRITTER LANE CHRONICLES the summary of an interesting point. You can position the text box THE NEWSLETTER OF THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF JEFFERSON COUNTY anywhere in the document. Use the Drawing Tools tab to change the formatting of the pull quote text box.] December, 2012: A Season of Giving As the Humane Society of Jefferson County nears the end of the first year of operating the shelter, between 750 and 800 animals will have come into our care. I want to thank the many supporters of the Humane Society who made it possible to provide the shelter and care for these animals when there was nowhere else for them to go. Those who have been kind enough to make a donation to the shelter allow us to provide food, medical care, and supplies. The businesses who have supported the shelter in so many different ways are appreciated and deserve the support of the community. Without all of you the fates of these animals would have been very different. Please consider making a donation to the Humane Society during the holiday season to help insure there will always be a shelter for animals in need. A donation to HSJC is perfect for anyone on your gift list; they will receive a lovely holiday card advising them of the gift you made in their name. –Paul Becker From all at the shelter we wish you and your companionA Stormy animals Lifea very Happy Holiday Season. by Susan Johnson Paul Becker When Stormy first came to the shelter we weren’t sure if she was named for her looks (she’s a handsome short-haired, Russian Blue type) or her temperament. -

19Th International Congress on Medieval Studies

mea1eva1HE1· ~ 1 INSTI1UTE international congress on medieval studies — GENERAL INFORMATION — REGISTRATION Everyone attending the Congress must fill out the official Registration Form and pay the $40.00 regular fee or $15.00 student fee. This registra tion fee is non-refundable. To save time upon arrival, we urge you to pre-register by mail before the April 1 deadline. Since University Food Services and the Housing Office need advance notification of the expected number of guests in order to make adequate arrangements, only advance registration will assure each person of an assigned room and the correct number of meal tickets waiting at the time of arrival. We regret that we cannot take registrations or reservations by phone. If you wish confirmation, include a stamped, self-addressed post card. TO PRE-REGISTER Fill out the enclosed registration form and mail all copies of the form, together with your check or money order, to THE MEDIEVAL INSTITUTE, WESTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY, KALAMAZOO, MICHIGAN 49008, before April 1. Only checks or money orders made out in U.S. dollars will be accepted. Foreign residents should use international money orders. The registration form is for ONE person only. If you wish to register and pay fees for another person, or share a room with another person, request additional registration forms from the Medieval Institute and send them to the Institute together. Refunds for housing and meals can be made only if the Medieval Institute receives notification of cancellation by April 15, 1984. NOTE: Please check and recheck figures before making out a check or money order and submitting the registration form. -

Lo Chansonnier Du Roi Luoghi E Autori Della Lirica E Della Musica Europee Del Duecento

Lo Chansonnier du Roi Luoghi e autori della lirica e della musica europee del Duecento Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia Dottorato in Musica e Spettacolo Curriculum di Storia e Analisi delle Culture Musicali Candidato Alexandros Maria Hatzikiriakos Tutor Co-Tutor Prof. Emanuele Giuseppe Senici Prof. Davide Daolmi a Niccolò Ringraziamenti Seppur licenziata sotto il nome di un solo autore, questa tesi ha raccolto una considerevole quantità di debiti, nel corso dei suoi tre anni di gestazione, che mi è impossibile ignorare. Agli studi e al prezioso aiuto di Stefano Asperti devo non solo il fondamento di questo lavoro, ma anche un supporto indispensabile. Parimenti ad Anna Radaelli, sono grato per un sostegno costante, non solo scientifico ma anche morale ed emotivo. Non di meno, i numerosi consigli di Emma Dillon, spesso accompagnati da confortanti tazze di caffè nero e bollente, mi hanno permesso di (ri-)trovare ordine nel coacervo di dati, intuizioni e deduzioni che ho dovuto affrontare giorno dopo giorno. A Simon Gaunt devo un prezioso aiuto nella prima e confusa fase della mia ricerca. A Marco Cursi e Stefano Palmieri devo una paziente consulenza paleografica e a Francesca Manzari un’indispensabile expertise sulle decorazioni del Roi. Ringrazio inoltre Davide Daolmi per la guida, il paziente aiuto e le numerose “pulci”; Maria Teresa Rachetta, filologa romanza, per aver lavorato e presentato con me i primi frutti di questa ricerca, lo Chansonnier du Roi per avermi dato l’opportunità di conoscere Maria Teresa Rachetta, l’amica; Livio Giuliano per ragionamenti improbabili ad ore altrettanto improbabili, sulla sociologia arrageois; Cecilia Malatesta e Ortensia Giovannini perché … il resto nol dico, già ognuno lo sa. -

February 2021

Emmanuel Lutheran Church One church...multiple communities February 2021 Mooring Line Drive Campus 777 Mooring Line Dr. Naples, FL 34102 239-261-0894 Sunday Services during the pandemic In-person services: 9:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m. - Traditional Service in Sanctuary 10:00 a.m. - Contemporary Alive Service in the Family Life Center 11:30 a.m. - Bilingual Service in the Family Life Center 9:00 a.m., 10:00 a.m. and 11:30 a.m. will be livestreamed as well. www.naplesemmanuel.org (Check out the “Weekly Schedule” on our Home Page) 10:00 a.m. - Drive-In Service at Emmanuel Park 2770 Oil Well Road, Naples, FL 34120 Email: [email protected] Our Mission: A Christ-centered community where God’s Spirit guides our lives as we worship, learn, love, share and serve. Staff and Church Council Our Staff: Rev. Steven E Wigdahl, Senior Pastor - [email protected] Rev. Dr. Rick Bliese, Associate Pastor - [email protected] Rev. José Lebrón, Associate Pastor for Mission Development - [email protected] Rev. William Kittinger, Associate Pastor for Mission Development - [email protected] Karole Langset, Resident Pastor - [email protected] Lois Sorensen, Resident Pastor - [email protected] Jim Cooper, ELCA Deacon, Youth & Family - [email protected] Frine Donadelli, Administrative Assistant at Pebblebrooke - [email protected] Gina Fidler, Office Manager - [email protected] Joyce Finlay, ELCA Deacon, Music & Worship; organist - [email protected] Carol Hartman, Parish Nurse -

1/24/2020 8:15 AM Warrant Listing WRNTLST Active Warrants from 1/01/2000 to 1/24/2020

1/24/2020 8:15 AM Warrant Listing WRNTLST Page: 1 Active Warrants From 1/01/2000 to 1/24/2020 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Name.................................... Warrant #... R/S DOB........ Issued.... Offense.............................. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ABBY, BYRON DONNELL E031621 -01 B/M 1/25/1977 7-26-2016 FAIL TO MAINTAIN FINANCIAL RESPONSI CP E031621 -02 7-26-2016 NO SEAT BELT - DRIVER CP ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ADAMS, BRADLEY JACOB F5668 -02 W/M 4/18/1998 9-04-2019 NO SEAT BELT - DRIVER CP ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ADAMS, BRYAN LEWIS F5477 -01 W/M 9/21/1985 6-26-2019 FAIL TO MAINTAIN FINANCIAL RESPONSI AW ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ADAMS, CHARLES RAY E035733 -01 W/M 1/26/1970 3-07-2017 FAIL TO MAINTAIN FINANCIAL RESPONSI CP E035733 -02 3-07-2017 DRIVING WHILE LICENSE INVALID CP E035733 -03 3-07-2017 EXPIRED REGISTRATION CP ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ADAMS, DANIEL JAMES 0683203 -01 W/M 7/18/1969 -

New Oxford History of Music Volume Ii

NEW OXFORD HISTORY OF MUSIC VOLUME II EDITORIAL BOARD J. A. WESTRUP (Chairman) GERALD ABRAHAM (Secretary) EDWARD J. DENT DOM ANSELM'HUGHES BOON WELLESZ THE VOLUMES OF THE NEW OXFORD HISTORY OF MUSIC I. Ancient and Oriental Music ii. Early Medieval Music up to 1300 in. Ars Nova and the Renaissance (c. 1300-1540) iv. The Age of Humanism (1540-1630) v. Opera and Church Music (1630-1750) vi. The Growth of Instrumental Music (1630-1750) vn. The Symphonic Outlook (1745-1790) VIIL The Age of Beethoven (1790-1830) ix. Romanticism (1830-1890) x. Modern Music (1890-1950) XL Chronological Tables and General Index ' - - SACRED AND PROFANE MUSIC (St. John's College, MS. B. Cambridge, 18.) Twelfth century EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC UP TO BOO EDITED BY DOM ANSELM HUGHES GEOFFREY CUMBERLEGE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON NEWYORK TORONTO 1954 Oxford University Press, Amen House, London E.C.4 GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI CAPE TOWN IBADAN Geoffrey Cumberlege, Publisher to the University PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN GENERAL INTRODUCTION THE present work is designed to replace the Oxford History of Music, first published in six volumes under the general editorship of Sir Henry Hadow between 1901 and 1905. Five authors contributed to that ambitious publication the first of its kind to appear in English. The first two volumes, dealing with the Middle Ages and the sixteenth century, were the work of H. E. Wooldridge. In the third Sir Hubert Parry examined the music of the seventeenth century. The fourth, by J. A. Fuller-Maitland, was devoted to the age of Bach and Handel; the fifth, by Hadow himself, to the period bounded by C. -

Babies' First Forenames: Births Registered in Scotland in 1986

Babies' first forenames: births registered in Scotland in 1986 Information about the basis of the list can be found via the 'Babies' First Names' page on the National Records of Scotland website. Boys Girls Position Name Number of babies Position Name Number of babies 1 David 1623 1 Laura 1038 2 Christopher 1292 2 Claire 876 3 Andrew 1178 3 Nicola 813 4 James 1100 4 Jennifer 782 5 John 1090 5 Sarah 698 6 Craig 984 6 Emma 667 7 Steven 946 7 Kirsty 633 8 Michael 891 8 Lisa 555 9 Scott 842 9 Michelle 519 10 Mark 832 10 Louise 513 11 Paul 816 11 Ashley 467 12 Robert 652 12 Amanda 463 13 Stuart 626 13 Samantha 425 14 Ross 591 14 Stephanie 418 15 Stephen 580 15 Fiona 386 16 Gary 577 16 Stacey 370 17 Kevin 567 17 Karen 360 18 William 552 18 Gemma 349 19 Jamie 465 19 Lauren 336 20 Martin 456 20 Gillian 329 21 Ryan 444 21 Natalie 296 22 Alan 422 22 Kerry 271 23= Graeme 419 23 Victoria 264 23= Thomas 419 24 Cheryl 263 25 Daniel 415 25 Amy 262 26 Darren 371 26 Heather 259 27 Richard 367 27 Kelly 249 28 Sean 336 28 Rachel 240 29 Colin 314 29 Lynsey 238 30 Alexander 305 30 Leanne 232 31 Peter 296 31 Donna 227 32 Iain 291 32 Charlene 219 33 Lee 276 33 Rebecca 218 34 Ian 269 34 Alison 217 35 Brian 268 35 Julie 215 36 Graham 260 36 Susan 205 37 Matthew 258 37 Angela 197 38 Gordon 252 38 Joanne 195 39 Barry 247 39 Pamela 193 40 Adam 241 40 Deborah 189 41 Gavin 236 41 Nicole 188 42 Jonathan 234 42 Catherine 185 43 Neil 226 43 Danielle 184 44 Allan 209 44 Elizabeth 175 45 Marc 206 45 Jenna 169 46 Kenneth 196 46 Jacqueline 165 47 Kyle 194 47= Caroline 159