Three Fifteenth-Century Collections of Communal Song A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AS WE RECALL the Growth of Agricultural Estimates^ 1933-1961 L M Brooks

^t^f.t.i^A^( fk^^^ /^v..<. S AS WE RECALL The Growth of Agricultural Estimates^ 1933-1961 L M Brooks Statistical Reporting s Service U.S. Department of Agriculture Washington, D.C As We Recall, THE GROWTH OF AGRICULTURAL ESTIMATES, 1933-1961 U.S. OEPÎ. or AGRlCUtTURE NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL UBRARY OECIT CATALOGmC PREP E. M. Brooks, Statistical Reporting Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture 1977 I FOREWORD The Statistical Reporting Service, as with any organization, needs to know its past to understand the present and appraise the future. Accordingly, our technical procedures are peri- ^odically set forth in ''Scope and Methods of the Statistical Reporting Service," and the agency's early development and program expansion were presented in "The Story of Agricultural Estimates." However, most important are the people who de- veloped this complex and efficient statistical service for agriculture and those who maintain and expand it today. Dr. Harry C. Trelogan, SRS Administrator, 1961-1975, arranged for Emerson M. Brooks to prepare this informal account of some of the people who steered SRS's course from 1933 to 1961. The series of biographical sketches selected by the author are representative of the people who helped develop the per- sonality of SRS and provide the talent to meet challenges for accurate and timely agricultural information. This narrative touching the critical issues of that period and the way they'^ were resolved adds to our understanding of the agency and helps maintain the esprit de corps that has strengthened our work since it started in 1862. Our history provides us some valuable lessons, for "those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." W. -

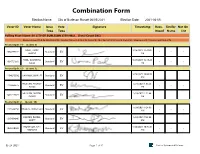

Combination Form

Combination Form Election Name: City of Burleson Runoff 06/05/2021 Election Date: 2021-06-05 Voter ID Voter Name Issue Vote Signature Timestamp Reas. Similar Not On Type Type Imped Name List Polling Place Name: EV CITY OF BURLESON CITY HALL (Total Count:245) Reason Imped (Y-0, N-245, Net-245) : Similar Name (Y-0, N-245, Net-245) : Not On List (Y-0, N-245, Net-245) : Standard-245, Provisional-0, Net-245 Precinct Split: 11- (Count: 2) POOL, LARRY 5/24/2021 12:45:02 1034793222 Standard EV - - - WAYNE PM POOL, DAVONNA 5/24/2021 12:45:28 1034721699 Standard EV - - - GAILE PM Precinct Split: 12- (Count: 3) 5/24/2021 10:08:30 1184023930 VAN NOY, JONI LEE Standard EV - - - AM MILBURN, AUDREY 5/24/2021 1:36:23 1146862575 Standard EV - - - RENEE PM MILBURN, DUSTIN 5/24/2021 2:51:44 1057217877 Standard EV - - - EVANS PM Precinct Split: 2- (Count: 14) 5/24/2021 9:24:06 1155522950 BASDEN, AMBER LEA Standard EV - - - AM BASDEN, DANIEL 5/24/2021 9:24:48 1215434046 Standard EV - - - SCOTT AM THOMPSON, KATI 5/24/2021 10:36:46 1050370989 Standard EV - - - MORGAN AM 05-24-2021 Page 1 of 21 Election Systems and Software Combination Form CRINER, JOAQUIN 5/24/2021 11:43:35 1052537873 Standard EV - - - RENE AM BOEDEKER, ALEXA 5/24/2021 11:45:30 1060105870 Standard EV - - - DANIELLE AM HOLMS, BARBARA 5/24/2021 11:59:40 1211090562 Standard EV - - - ANN AM HOLMS, BRADFORD 5/24/2021 12:00:52 1211090527 Standard EV - - - ANDREW PM 5/24/2021 12:33:18 2177469793 MABRY, ERIN NICOLE Standard EV - - - PM MABRY, TIMOTHY 5/24/2021 12:43:27 1200041381 Standard EV - - - -

2020-Commencement-Program.Pdf

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT 2020 Conferring of degrees at the close of the 144th academic year MAY 21, 2020 1 CONTENTS Degrees for Conferral .......................................................................... 3 University Motto and Ode ................................................................... 8 Awards ................................................................................................. 9 Honor Societies ................................................................................. 20 Student Honors ................................................................................. 25 Candidates for Degrees ..................................................................... 35 2 ConferringDegrees of Degrees for Conferral on Candidates CAREY BUSINESS SCHOOL Masters of Science Masters of Business Administration Graduate Certificates SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Doctors of Education Doctors of Philosophy Post-Master’s Certificates Masters of Science Masters of Education in the Health Professions Masters of Arts in Teaching Graduate Certificates Bachelors of Science PEABODY CONSERVATORY Doctors of Musical Arts Masters of Arts Masters of Audio Sciences Masters of Music Artist Diplomas Graduate Performance Diplomas Bachelors of Music SCHOOL OF NURSING Doctors of Nursing Practice Doctors of Philosophy Masters of Science in Nursing/Advanced Practice Masters of Science in Nursing/Entry into Nursing Practice SCHOOL OF NURSING AND BLOOMBERG SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH Masters of Science in Nursing/Masters of Public -

The Development of Musical Notation Carolyn S

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2015 yS mposium Apr 1st, 2:20 PM - 2:40 PM Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The Development of Musical Notation Carolyn S. Gorog Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Composition Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Gorog, Carolyn S., "Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The eD velopment of Musical Notation" (2015). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 5. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2015/podium_presentations/5 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The development of Musical Notation Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The Development of Musical Notation Music has been around for a long time; in almost every culture around the world we find evidence of music. Music throughout history started as mostly vocal music, it was transmitted orally with no written notation. During the early ninth and tenth century the written tradition started to be seen and developed. This marked the beginnings of music notation. Music notation has gone through many stages of development from neumes, square notes, and four-line staff, to modern notation. Although modern notation works very well, it is not necessarily superior to methods used in the Renaissance and Medieval periods. In Western music neumes are the name given to the first type of notation used. -

One Hundred Fifteenth Congress of the United States of America

H. R. 1892 One Hundred Fifteenth Congress of the United States of America AT THE SECOND SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Wednesday, the third day of January, two thousand and eighteen An Act To amend title 4, United States Code, to provide for the flying of the flag at half-staff in the event of the death of a first responder in the line of duty. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018’’. DIVISION A—HONORING HOMETOWN HEROES ACT SECTION 10101. SHORT TITLE. This division may be cited as the ‘‘Honoring Hometown Heroes Act’’. SEC. 10102. PERMITTING THE FLAG TO BE FLOWN AT HALF-STAFF IN THE EVENT OF THE DEATH OF A FIRST RESPONDER SERVING IN THE LINE OF DUTY. (a) AMENDMENT.—The sixth sentence of section 7(m) of title 4, United States Code, is amended— (1) by striking ‘‘or’’ after ‘‘possession of the United States’’ and inserting a comma; (2) by inserting ‘‘or the death of a first responder working in any State, territory, or possession who dies while serving in the line of duty,’’ after ‘‘while serving on active duty,’’; (3) by striking ‘‘and’’ after ‘‘former officials of the District of Columbia’’ and inserting a comma; and (4) by inserting before the period the following: ‘‘, and first responders working in the District of Columbia’’. (b) FIRST RESPONDER DEFINED.—Such subsection is further amended— (1) in paragraph (2), by striking ‘‘, United States Code; and’’ and inserting a semicolon; (2) in paragraph (3), by striking the period at the end and inserting ‘‘; and’’; and (3) by adding at the end the following new paragraph: ‘‘(4) the term ‘first responder’ means a ‘public safety officer’ as defined in section 1204 of title I of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 (34 U.S.C. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

Plainchant Tradition*

Some Observations on the "Germanic" Plainchant Tradition* By Alexander Blachly Anyone examining the various notational systems according to which medieval scribes committed the plainchant repertory to written form must be impressed both by the obvious relatedness of the systems and by their differences. There are three main categories: the neumatic notations from the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries (written without a staff and incapable, therefore, of indicating precise pitches);1 the quadratic nota tion in use in Italy, Spain, France, and England-the "Romanic" lands from the twelfth century on (this is the "traditional" plainchant notation, written usually on a four-line staff and found also in most twentieth century printed books, e.g., Liber usualis, Antiphonale monasticum, Graduale Romanum); and the several types of Germanic notation that use a staff but retain many of the features of their neumatic ancestors. The second and third categories descended from the first. The staffless neumatic notations that transmit the Gregorian repertory in ninth-, tenth-, and eleventh-century sources, though unlike one another in some important respects, have long been recognized as transmitting the same corpus of melodies. Indeed, the high degree of concordance between manuscripts that are widely separated by time and place is one of the most remarkable aspects the plainchant tradition. As the oldest method of notating chant we know,2 neumatic notation compels detailed study; and the degree to which the neumatic manuscripts agree not only • I would like to thank Kenneth Levy, Alejandro Plan chart, and Norman Smith for reading this article prior to publication and for making useful suggestions for its improve ment. -

108 Melodies

SRI SRI HARINAM SANKIRTAN - l08 MELODIES - INDEX CONTENTS PAGE CONTENTS PAGE Preface 1-2 Samant Sarang 37 Indian Classical Music Theory 3-13 Kurubh 38 Harinam Phylosphy & Development 14-15 Devagiri 39 FIRST PRAHAR RAGAS (6 A.M. to 9 A.M.) THIRD PRAHAR RAGAS (12 P.M. to 3 P.M.) Vairav 16 Gor Sarang 40 Bengal Valrav 17 Bhimpalasi 4 1 Ramkal~ 18 Piloo 42 B~bhas 19 Multani 43 Jog~a 20 Dhani 44 Tori 21 Triveni 45 Jaidev 22 Palasi 46 Morning Keertan 23 Hanskinkini 47 Prabhat Bhairav 24 FOURTH PKAHAR RAGAS (3 P.M. to 6 P.M.) Gunkali 25 Kalmgara 26 Traditional Keertan of Bengal 48-49 Dhanasari 50 SECOND PRAHAR RAGAS (9 A.M. to 12 P.M.) Manohar 5 1 Deva Gandhar 27 Ragasri 52 Bha~ravi 28 Puravi 53 M~shraBhairav~ 29 Malsri 54 Asavar~ 30 Malvi 55 JonPurl 3 1 Sr~tank 56 Durga (Bilawal That) 32 Hans Narayani 57 Gandhari 33 FIFTH PRAHAR RAGAS (6 P.M. to 9 P.M.) Mwa Bilawal 34 Bilawal 35 Yaman 58 Brindawani Sarang 36 Yaman Kalyan 59 Hem Kalyan 60 Purw Kalyan 61 Hindol Bahar 94 Bhupah 62 Arana Bahar 95 Pur~a 63 Kedar 64 SEVENTH PRAHAR RAGAS (12 A.M. to 3 A.M.) Jaldhar Kedar 65 Malgunj~ 96 Marwa 66 Darbar~Kanra 97 Chhaya 67 Basant Bahar 98 Khamaj 68 Deepak 99 Narayani 69 Basant 100 Durga (Khamaj Thhat) 70 Gaur~ 101 T~lakKarnod 71 Ch~traGaur~ 102 H~ndol 72 Shivaranjini 103 M~sraKhamaj 73 Ja~tsr~ 104 Nata 74 Dhawalsr~ 105 Ham~r 75 Paraj 106 Mall Gaura 107 SIXTH PRAHAR RAGAS (9Y.M. -

Battlefieldbam

2016 BAM Next Wave Festival #BattlefieldBAM Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Battlefield BAM Harvey Theater Sep 28—30, Oct 1, 4—9 at 7:30pm Oct 1, 8 & 9 at 2pm; Oct 2 at 3pm Running time: approx. one hour & 10 minutes, no intermission C.I.C.T.—Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord Based on The Mahabharata and the play written by Jean-Claude Carrière Adapted and directed by Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne Music by Toshi Tsuchitori Costume design by Oria Puppo Lighting design by Phillippe Vialatte With Carole Karemera Jared McNeill Ery Nzaramba Sean O’Callaghan Season Sponsor: Major support for theater at BAM provided by: The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust Donald R. Mullen Jr. The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. Battlefield Photos: Simon Annand CAROLE KAREMERA JARED MCNEILL ERY NZARAMBA SEAN O’CALLAGHAN TOSHI TSUCHITORI Stage manager Thomas Becelewski American Stage Manager R. Michael Blanco The Actors are appearing with the permission of Actors’ Equity Association. The American Stage Manager is a member of Actors’ Equity Association. COPRODUCTION The Grotowski Institute; PARCO Co. Ltd / Tokyo; Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg; Young Vic Theatre / London; Singapore Repertory Theatre; Le Théâtre de Liège; C.I.R.T.; Attiki Cultural Society / Athens; Cercle des partenaires des Bouffes du Nord Battlefield DIRECTORS’ STATEMENT The Mahabharata is not simply a book, nor a great series of books, it is an immense canvas covering all the aspects of human existence. -

Shamanism Mother Earth’S Children Spiritual Aging and Dying Your Body Holds the Secret Healing Through Hakomi

FREE! awareness e xploring spirituality Shamanism Mother Earth’s Children Spiritual Aging and Dying Your Body Holds the Secret Healing Through Hakomi South River Highlands Country Retreat Good Vibes Wellness Richmond Hill ...and more! OCTOBER 2016 Bridge Between the Worlds Spiritual Retreat Center Charlottesville, Virginia Multipurpose Facilities Transformational Classes Relaxing Spa Offerings Private Lodging Available A Serene Venue for Seminars, Personal Retreats and Weddings Contact us at www.bbtw.org (434) 293-9708 2 October 2016 awareness exploring spirituality THE HAKOMI METHOD Compassionate Self-Discovery • Come alive in ways you never have before! • Let your body’s wisdom guide you to wholeness & healing • Finally work effectively with all aspects of yourself www.compassionateselfawareness.com Virginia’s only Certified Hakomi Practitioner Jocelyn Pierce Audet CHP Charlottesville and Staunton offices Self-Awareness & Mindfulness Coaching Available by Skype & in person Mental Health Nutrition [email protected] 540.290.6138 www.exploreawareness.com October 2016 3 welcome to … The Awareness family is excited to announce the expansion of our social media presence with upgrades to Facebook (www.facebook.com/ exploreawareness), and Twitter (@exploreawarenes). Please “like” and “follow” us to spread the word and expand Virginia’s community of the spiritually aware. Write us at; Awareness LLC P.O. Box 85 • North Garden, VA 22959 or email [email protected] To advertise with us; Call (434) 972-9273 Or email: [email protected] NEXT ISSUE – JANUARY 2017 4 October 2016 awareness exploring spirituality LETTER FROM THE Publisher... “Alternative lifestyle” … “Alternative belief system” … “Alternative medicine” When I grab my trusty old and well-worn Webster’s VOLUME 1 ISSUE 4 OCTOBER 2016 Dictionary and look up the word alternative, I find .. -

CRITTER LANE CHRONICLES the Summary of an Interesting Point

[Type a quote from the document or CRITTER LANE CHRONICLES the summary of an interesting point. You can position the text box THE NEWSLETTER OF THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF JEFFERSON COUNTY anywhere in the document. Use the Drawing Tools tab to change the formatting of the pull quote text box.] December, 2012: A Season of Giving As the Humane Society of Jefferson County nears the end of the first year of operating the shelter, between 750 and 800 animals will have come into our care. I want to thank the many supporters of the Humane Society who made it possible to provide the shelter and care for these animals when there was nowhere else for them to go. Those who have been kind enough to make a donation to the shelter allow us to provide food, medical care, and supplies. The businesses who have supported the shelter in so many different ways are appreciated and deserve the support of the community. Without all of you the fates of these animals would have been very different. Please consider making a donation to the Humane Society during the holiday season to help insure there will always be a shelter for animals in need. A donation to HSJC is perfect for anyone on your gift list; they will receive a lovely holiday card advising them of the gift you made in their name. –Paul Becker From all at the shelter we wish you and your companionA Stormy animals Lifea very Happy Holiday Season. by Susan Johnson Paul Becker When Stormy first came to the shelter we weren’t sure if she was named for her looks (she’s a handsome short-haired, Russian Blue type) or her temperament. -

Basic Music Course: Keyboard Course

B A S I C M U S I C C O U R S E KEYBOARD course B A S I C M U S I C C O U R S E KEYBOARD COURSE Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah © 1993 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Updated 2004 English approval: 4/03 CONTENTS Introduction to the Basic Music Course .....1 “In Humility, Our Savior”........................28 Hymns to Learn ......................................56 The Keyboard Course..................................2 “Jesus, the Very Thought of Thee”.........29 “How Gentle God’s Commands”............56 Purposes...................................................2 “Jesus, Once of Humble Birth”..............30 “Jesus, the Very Thought of Thee”.........57 Components .............................................2 “Abide with Me!”....................................31 “Jesus, Once of Humble Birth”..............58 Advice to Students ......................................3 Finding and Practicing the White Keys ......32 “God Loved Us, So He Sent His Son”....60 A Note of Encouragement...........................4 Finding Middle C.....................................32 Accidentals ................................................62 Finding and Practicing C and F...............34 Sharps ....................................................63 SECTION 1 ..................................................5 Finding and Practicing A and B...............35 Flats........................................................63 Getting Ready to Play the Piano