Building Societies Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference Banks / Finance Address

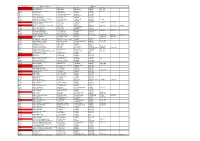

Reference Banks / Finance Address B/F2 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F262 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F57 Abbey National Treasury Services Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F168 ABN Amro Bank 199 Bishopsgate LONDON EC2M 3TY B/F331 ABSA Bank Ltd 52/54 Gracechurch Street LONDON EC3V 0EH B/F175 Adam & Company Plc 22 Charlotte Square EDINBURGH EH2 4DF B/F313 Adam & Company Plc 42 Pall Mall LONDON SW1Y 5JG B/F263 Afghan National Credit & Finance Ltd New Roman House 10 East Road LONDON N1 6AD B/F180 African Continental Bank Plc 24/28 Moorgate LONDON EC2R 6DJ B/F289 Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (AMC) AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER Hampshire SP10 1DE B/F147 AIB Capital Markets Plc 12 Old Jewry LONDON EC2 B/F290 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Lending Girobank Bootle Centre Bridal Road BOOTLE Merseyside GIR 0AA B/F67 Alliance & Leicester Plc Carlton Park NARBOROUGH LE9 5XX B/F264 Alliance & Leicester plc 49 Park Lane LONDON W1Y 4EQ B/F110 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd PO Box 164 Meadow House 64 Reform Street DUNDEE DD1 9YP B/F32 Allied Bank of Pakistan Ltd 62-63 Mark Lane LONDON EC3R 7NE B/F134 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row LONDON SW1P B/F291 Allied Irish Bank Plc Commercial Banking Bankcentre Belmont Road UXBRIDGE Middlesex UB8 1SA B/F8 Amber Homeloans Ltd 1 Providence Place SKIPTON North Yorks BD23 2HL B/F59 AMC Bank Ltd AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER SP10 1DD B/F345 American Express Bank Ltd 60 Buckingham Palace Road LONDON SW1 W B/F84 Anglo Irish -

170Th Anniversary Society Celebrates Success Spanning Three Centuries

SoIssue 8 • Spring 2018 ciety G MEM DIN B R ER A S W H I E FOR P R • • S 1 0 C 7YEARS O Y T 1848-2018 T T IE I C SH O B S UILDING 170th Anniversary Society celebrates success spanning three centuries The magazine of Inside: Welcome THIS year sees Scottish in this issue we visit Marsie Stuart Fulfilling our promise to offer Building Society reach its 170th in Troon who has been awarded our best available rates anniversary. Like the bridges the British Empire Medal in Page 3 crossing the River Forth on the recognition of her contribution to Five minutes with cover of this issue, your Society teaching British Sign Language, Drew Ferguson has spanned three centuries and young couple Nikki Watson Page 4 where much has changed, but the and Gregor Steedman who have importance we place on fairness bought their first home with the Lifetime mortgage is a lifeline and community remain the same. help of a Professional Mortgage. for British Empire Medal As Scotland’s only independent Thank you to everyone who winner building society, and the oldest voted for the local charities you Page 5 in the world, we marked the would like us to support in the Scottish Building Society occasion with a reception at the coming year. 170th Anniversary Scottish Parliament. Hosted for The results are in and we are Page 6 us by our constituency MSP Ruth gearing up to support the good Davidson, it was a pleasure to causes you have chosen. If you Our charities of the year 2018 see members rub shoulders with would like to be involved, please Page 8 cross party politicians, staff past contact your local branch. -

Scotland Analysis: Financial Services and Banking

Scotland analysis: financial services and banking Calculating the size of the Scottish banking sector relative to Scottish GDP The Treasury’s paper Scotland analysis: financial services and banking outlines that: • Banking sector assets for the whole UK at present are around 492 per cent of GDP. • The Scottish banking sector, by comparison, would be extremely large in the event of independence. It currently stands at around 1254 per cent of Scotland’s GDP. Data on total assets of the Scottish financial sector was provided to the Treasury by the Financial Services Authority (FSA), which was the regulator of all UK financial services firms up until 1 April 2013, when it was replaced by the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). As the paper sets out, the analysis proceeds on the basis that firms whose headquarters or principal place of business are in Scotland are to be considered ‘Scottish’ firms. Further information about where individual firms are located is available from the financial services register, which is available from www.fca.org.uk/register/ When considering groups, legal entities are treated on an individual basis, rather than the whole group being classified as either Scottish or ‘rest of the UK’. For example within RBS group, Royal Bank of Scotland PLC is treated as a Scottish firm, but National Westminster Bank PLC is treated as a ‘rest of the UK’ firm: although it is part of RBS group, it is separately authorised and headquartered in London. The regulator is not able to provide data for publication about the size of assets held by individual firms, as there are restrictions on the sharing of firm-specific regulatory data. -

Rpt MFI-EU Hard Copy Annual Publication

MFI ID NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CITY HEAD OFFICE RES* UNITED KINGDOM Central Banks GB0425 Bank of England Threadneedle Street EC2R 8AH London No Total number of Central Banks : 1 Credit Institutions GB0005 3i Group plc 91 Waterloo Road SE1 8XP London No GB0015 Abbey National plc Abbey National House, 2 Triton NW1 3AN London No Square, Regents Place GB0020 Abbey National Treasury Services plc Abbey National House, 2 Triton NW1 3AN London No Square, Regents Place GB0025 ABC International Bank 1-5 Moorgate EC2R 6AB London No GB0030 ABN Amro Bank NV 10th Floor, 250 Bishopsgate EC2M 4AA London NL ABN AMRO Bank N.V. No GB0032 ABN AMRO Mellon Global Securities Services Princess House, 1 Suffolk Lane EC4R 0AN London No BV GB0035 ABSA Bank Ltd 75 King William Street EC4N 7AB London No GB0040 Adam & Company plc 22 Charlotte Square EH2 4DF Edinburgh No GB2620 Ahli United Bank (UK) Ltd 7 Baker Street W1M 1AB London No GB0050 Airdrie Savings Bank 56 Stirling Street ML6 OAW Airdrie No GB1260 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Bank plc Building One, Narborough LE9 5XX Leicester No GB0060 Alliance and Leicester plc Building One, Floor 2, Carlton Park, LE10 0AL Leicester No Narborough GB0065 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd Meadow House, 64 Reform Street DD1 1TJ Dundee No GB0075 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row SW1P 1JQ London No GB0087 Allied Irish Bank (GB) / First Trust Bank - AIB 51 Belmont Road, Uxbridge UB8 1SA Middlesex No Group (UK) plc GB0080 Allied Irish Banks plc 12 Old Jewry EC2R 8DP London IE Allied Irish Banks plc No GB0095 Alpha Bank AE 66 Cannon Street EC4N 6AE London GR Alpha Bank, S.A. -

Coding and Editing Instructions

Appendix C Coding And Editing Instructions Version 2: December 2004 P2321 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70) 2004 Survey Editor’s code book and CAPI edit instructions British Cohort Study: 2004-2005 Survey Technical Report 4 Introduction These instructions outline the coding and editing requirements for the BCS70 2004 Study. This document explains the editing tasks that you need to carry out and it contains the code frames you will need for coding. In this study, respondents are called ‘Cohort Members’ (CMs for short), and that is how they will be described in this document. This document should be used in conjunction with the BCS70 CAPI edit questionnaire. Background to the BCS70 2004 The 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70) began in 1970, when data was collected about over 16, 000 babies born in England, Scotland and Wales between 5th and 11th April 1970. Since then, the Cohort Members have been followed up five times, at ages 5, 10, 16, 26 and 30, to collect data about their health, educational, social and economic circumstances. NatCen carried out the most recent survey of the cohort in 1999/2000. The 2004 questionnaire has several elements including a Core interview (both CAPI and CASI) and assessments of basic skills. Half of the people in the sample are assigned to the Parent and Child survey. These CMs complete an additional module of the CAPI questionnaire (which focuses on their children) and their natural and/or adopted children complete some assessments. The Core (CAPI) questionnaire covers the following areas: • Housing • Partnerships -

FOI3002 Information Provided

Firm Ref Firm Name 100013 Skipton Financial Services Ltd 100014 Leek United Building Society 100015 Saffron Building Society 100017 SBCA 100129 Allotts 100163 Alexander Ash & Co Ltd 100266 Bevan & Buckland 100556 Oury Clark 100732 Alliotts 100747 Heywood Shepherd 100799 Forrester Boyd 100813 Gibbons 100820 Gilberts 100825 Greaves West & Ayre 100883 Friend-James 101012 Neville A. Joseph 101022 Howard Worth 101092 Javed & Co 101112 Lamont Pridmore 101117 Winningtons 101133 Gross Klein (incorporating Gross Klein Wood and Gross Klein & Partners) 101142 Larking Gowen 101163 Latif & Company 101180 Keymer Haslam & Co 101321 J.H. Greenwood & Company 101330 John Kerr 101494 Lovewell Blake 101501 McCabe Ford Williams 101566 Hamilton Brading 101579 Robinson and Co 101608 Pentins 101609 Peters, Elworthy & Moore 101633 Palmer, Riley & Co 101739 Nicholsons 101840 Price Mann & Co 101886 Leftley, Rowe & Company 102046 Mitchell Charlesworth 102167 Playfoot & Company 102245 Stephenson & Co 102323 Volans, Leach & Schofield 102395 Whitakers 102411 Shelvoke, Pickering, Janney & Co 102529 Trudgeon Halling 102531 Uppal & Warr 102557 Shah Dodhia & Co 102577 Wildin & Co 102581 Gerald Thomas & Co 102677 Arthur E Walker & Co 102722 BSG Valentine 102781 Pierce 102903 Winburn Glass Norfolk 102983 Mark J Rees 103410 Sedley Richard Laurence Voulters 103440 Leonard Gold 103630 Tyas & Company 103677 Daly, Hoggett & Co 103876 Sandison Easson & Co 104021 Sampson West 104101 Geo Little Sebire & Co 104219 M. Emanuel 104354 Potter Baker 104433 Millener Davies 104538 Bird Simpson & Co 104673 Thomson Cooper 104732 Gilmour Hamilton & Co 104752 James S Lessells 104753 Walker, Dunnett & Co 104766 James Hair & Co 104875 Ipswich Building Society 104877 West Bromwich Building Society 104917 Armstrong Watson 104961 Morris Owen 104965 Mercer & Hole 104982 Strover, Leader & Co 105125 Hicks and Company 105181 Malthouse & Company Wealth Management 105402 H.B. -

REGISTRAR of Bltilding SOCIETIES

VICTORIA Report of the REGISTRAR OF BlTILDING SOCIETIES for the Year ended 30 June 1984 Ordered by the Legislative Assembly to be printed MELBOURNE F D ATKINSON GOVERNMENT PRINTER 1985 No 12. VICTORIA BUILDING SOCIETIES Seventh Annual ReJXlrt of the Registrar for the financial year ended 30 June 1984 The Honourable the Minister of Housing This reJXlrt, which is submitted pursuant to the provisions of section 113 of the Building Societies Act 1976 (No. 8966), relates to the period 1 July 1983 to 30 June 1984. A statistical and graphical summary of the operations of Permanent Building Societies and the Building Societies General Reserve Fund, to the close of the year under review, is presented in the supplement to the reJXlrt. GENERAL The year to 30 June, 1984 has been most eventful. The progressive deregulation of the fmancial system continued, generating new OpfKlrtunities and challenges for all finan cial institutions and in particular, building societies. Although the initiative in this area lies predominantly with the Federal Government, the States have an imJXlrtant reSJXln sibility with respect to those insitutions which operate under State legislation. Victoria took the lead in this area when the Government established the Financial Institutions Review in December 1983. The ReJXlrt of the Review was submitted to the resJXlnsible Ministers, the Hon. R. A. Jolly, M.P., Treasurer, and the Hon. I. A. Cathie, M.P., Minister of Housing, in May 1984. As Chairman of the Review Steering Committee, I acknowledge the contributions of my colleagues on the Committee and the work of the Review Team, in particular that of the Consultant to the Review, Mr. -

Banking: Law-Now Alerts, Tools and Latest News

Banking: Law-Now alerts, tools and latest news Law-Now alerts and other tools Law-Now: “ The Banking Standards Report: The new offence of reckless misconduct ” (18/07/13) Law Now: “ The Government responds to the Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards Report ” (12/07/13) Law-Now: “ Liability of Credit Rating Agencies – UK Regulations come into force on 25 July 2013 ” (10/07/13) Law-Now: “ Recent banking pay developments ” (25/06/13) Law-Now: “ Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards Final Report ” (25/06/13) Law-Now: “ The European Financial Transaction Tax - a levy sans frontieres ” (9/04/13) Law-Now: “ Disqualification may be on the horizon for former HBOS directors ” (9/04/13) Law Now: “ Interest Rate Derivative Mis-selling: A new case ” (9/01/13) Click here to access archived Law-Now alerts and other tools Click here to access more general news on remuneration Latest news Topics covered: Reforming the financial regulation of banks and credit rating agencies Payment systems and non-consumer banking Building societies and mutuals Reforming the financial regulation of banks and credit rating agencies HMT: A bank levy banding approach: consultation This consultation considers the case for a revenue neutral reform of the bank levy which would move away from the existing system of headline rates and towards a banding approach for determining banks’ charges under the levy. Responses are required by 8 May 2014. If the Government decides to make changes to the bank levy’s design in response to this consultation, the intention is to introduce legislation at the Report Stage of Finance Bill 2014 (currently expected to be in early July) with changes taking effect for chargeable periods beginning on or after 1 January 2015. -

Mfi Id Name Address Postal City Head Office Res* United Kingdom

MFI ID NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CITY HEAD OFFICE RES* UNITED KINGDOM Central Banks GB0425 Bank of England Threadneedle Street EC2R 8AH London No Total number of Central Banks : 1 Credit Institutions GB0015 Abbey National plc Abbey National House, 2 Triton NW1 3AN London No Square, Regents Place GB0020 Abbey National Treasury Services plc Abbey National House, 2 Triton NW1 3AN London No Square, Regents Place GB0025 ABC International Bank 1-5 Moorgate EC2R 6AB London No GB0030 ABN Amro Bank NV 10th Floor, 250 Bishopsgate EC2M 4AA London NL ABN AMRO Bank N.V. No GB0032 ABN AMRO Mellon Global Securities Services Princess House, 1 Suffolk Lane EC4R 0AN London No BV GB0035 ABSA Bank Ltd 75 King William Street EC4N 7AB London No GB0040 Adam & Company plc 22 Charlotte Square EH2 4DF Edinburgh No GB2620 Ahli United Bank (UK) Ltd 7 Baker Street W1M 1AB London No GB0050 Airdrie Savings Bank 56 Stirling Street ML6 OAW Airdrie No GB0043 Akbank NV 2nd Floor, 29 Marylebone Road NW1 5JX London No GB0056 Allfunds Bank SA Abbey House, 2 Triton Square, NW1 3AN London ES Allfunds Bank, S.A No Regents Place GB1260 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Bank plc Building One, Narborough LE9 5XX Leicester No GB0060 Alliance and Leicester plc Building One, Floor 2, Carlton Park, LE10 0AL Leicester No Narborough GB0065 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd Meadow House, 64 Reform Street DD1 1TJ Dundee No GB0075 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row SW1P 1JQ London No GB0087 Allied Irish Bank (GB) / First Trust Bank - AIB 51 Belmont Road, Uxbridge UB8 1SA Middlesex No Group (UK) plc GB0080 Allied Irish Banks plc 12 Old Jewry EC2R 8DP London IE Allied Irish Banks plc No GB0095 Alpha Bank AE 66 Cannon Street EC4N 6AE London GR Alpha Bank, S.A. -

Annual Report & Accounts

Annual Report & Accounts For the year ended 31 January 2018 Rewarding Membership Report & Accounts For the year ended 31 January 2018 “ I am delighted to report on another healthy set of financial results for a year that has seen both residential mortgage assets and retail savings balances increase, with Profit Before Tax, at £1.30 million, directly in line with our five-year-plan.” MARK L THOMSON CHIEF EXECUTIVE Contents Chairman’s Report 2 Chief Executive’s Review 4 Member Survey Results 2017 7 Society Key Results 8 Directors’ Report 10 Board of Directors 16 Corporate Governance Report 18 Directors’ Remuneration Report 23 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 25 Independent Auditor’s Report 26 Accounts Income Statement 30 Other Comprehensive Income 31 Statement of Financial Position 32 Statement of Changes in Members’ Interests 33 Cash Flow Statement 34 Notes to the Accounts 35 Annual Business Statement 69 Our Loyalty Promises 71 Our Branches 72 REPORT & ACCOUNTS for the year ended 31 January 2018 | 1 Chairman’s Report “ We are positive about the Society’s ability to remain strong and relevant and provide our members with attractive rates and excellent service.” RAYMOND ABBOTT CHAIRMAN 2 | REPORT & ACCOUNTS for the year ended 31 January 2018 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT of the developments in our selected charities. Questions for the AGM can be asked on the day or sent in advance. “ Your Society Details of sending questions are included in the Notice remains in a calling the AGM. strong financial FINANCIAL OVERVIEW position with Your Society remains in a strong financial position with a healthy capital base and liquidity. -

The Building Societies Association

Report for: The Building Societies Association An Analysis of the Relative Performance of UK Banks and Building Societies Prepared by Dr Barbara Casu Centre for Banking Research Cass Business School City University London 30 June 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary……………………………………………………2 1. BACKGROUND 1.1 The UK Economic Outlook……………………………………………………………………….3 2. AN OVERVIEW OF THE STRUCTURE OF THE UK BANKING SECTOR…………...…8 2.1 The Global Financial Crisis and Structural Reforms……………………………………….8 2.2 The Structure of the UK Banking Sector……………………………………………………10 3. THE ECONOMICS OF BUILDING SOCIETIES……………………………………………18 4. THE PERFORMANCE OF BUILDING SOCIETIES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS…22 4.1 Lending and Asset Growth……………………….……………………………………………24 4.2 Performance Indicators………………………………………………….……………………..27 4.3 Solvency and Stability Indicators…………………………………………………………….35 5. SUMMARY………………………………………………………….………………………….40 6. REFERENCES…………………………………………………………………………………41 Appendix 1: Demutualisation of the UK building society sector (1997 - 2015)………42 Appendix 2: Major British Banking Groups (MBBGs)…………………………………….44 Appendix 3: List of banks and building societies considered in this report…………48 1 Research objectives To evaluate the relative performance of UK building societies To compare the performance of building societies to that of commercial banks To understand the impact of the financial crisis and subsequent regulatory changes on UK building societies To offer an evaluation of the economic outlook for the UK’s building societies' sector EXECTUTIVE SUMMARY This report examines the performance of UK building societies since the large-scale demutualisation process ended in the year 2000. It considers the strengths and the weaknesses of the building society sector and their contribution to the financial industry, at a time where public confidence in the financial system and, in particular banks, is low. -

Annual Report & Accounts

Annual Report & Accounts For the year ended 31 January 2020 ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS for the year ended 31 January 2020 “ I have taken a great deal of confidence from the capability, capacity and resourcefulness within the business during an uncertain year, but it is our collective resilience that is key to our sustainable future.” PAUL DENTON CHIEF EXECUTIVE CONTENTS Page Chairman’s Report 2 Chief Executive’s Review 4 Society Key Results 6 Member Survey Results 2019 7 Directors’ Report 8 Board of Directors 14 Corporate Governance Report 16 Directors’ Remuneration Report 21 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 23 Independent Auditors’ Report 24 Accounts Income Statement 32 Statement of Other Comprehensive Income 33 Statement of Financial Position 34 Statement of Changes in Members’ Interests 35 Cash Flow Statement 36 Notes to the Accounts 37 Country by Country Reporting 71 Annual Business Statement 74 1 ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS for the year ended 31 January 2020 Chairman’s Report YOUR SOCIETY The year to 31 January 2020 has been another positive one for the Society. We maintained a strong and profitable financial position, albeit at a lower level than recent years due to a number of one-off costs as we transitioned to a new operating structure. Our results reflect a sixth consecutive year of mortgage book growth and strong growth in savings balances, against a backdrop of a highly competitive mortgage market and continued economic uncertainty. Indeed, at the time of writing, the effects of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in social and economic terms are severe and unprecedented in our lifetime.