Saskpower's Power Generation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Discovery Guide

saskatchewan discovery guide OFFICIAL VACATION AND ACCOMMODATION PLANNER CONTENTS 1 Contents Welcome.........................................................................................................................2 Need More Information? ...........................................................................................4 Saskatchewan Tourism Zones..................................................................................5 How to Use the Guide................................................................................................6 Saskatchewan at a Glance ........................................................................................9 Discover History • Culture • Urban Playgrounds • Nature .............................12 Outdoor Adventure Operators...............................................................................22 Regina..................................................................................................................... 40 Southern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 76 Saskatoon .............................................................................................................. 158 Central Saskatchewan ....................................................................................... 194 Northern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 276 Events Guide.............................................................................................................333 -

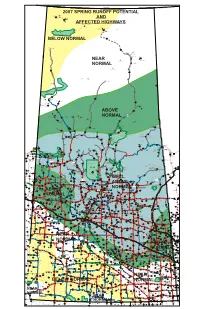

Spring Runoff Highway Map.Pdf

NUNAVUT TERRITORY MANITOBA NORTHWEST TERRITORIES 2007 SPRING RUNOFF POTENTIAL Waterloo Lake (Northernmost Settlement) Camsell Portage .3 999 White Lake Dam AND Uranium City 11 10 962 19 AFFECTEDIR 229 Fond du Lac HIGHWAYS Fond-du-Lac IR 227 Fond du Lac IR 225 IR 228 Fond du Lac Black Lake IR 224 IR 233 Fond du Lac Black Lake Stony Rapids IR 226 Stony Lake Black Lake 905 IR 232 17 IR 231 Fond du Lac Black Lake Fond du Lac ATHABASCA SAND DUNES PROVINCIAL WILDERNESS PARK BELOW NORMAL 905 Cluff Lake Mine 905 Midwest Mine Eagle Point Mine Points North Landing McClean Lake Mine 33 Rabbit Lake Mine IR 220 Hatchet Lake 7 995 3 3 NEAR Wollaston Lake Cigar Lake Mine 52 NORMAL Wollaston Lake Landing 160 McArthur River Mine 955 905 S e m 38 c h u k IR 192G English River Cree Lake Key Lake Mine Descharme Lake 2 Kinoosao T 74 994 r a i l CLEARWATER RIVER PROVINCIAL PARK 85 955 75 IR 222 La Loche 914 La Loche West La Loche Turnor Lake IR 193B 905 10 Birch Narrows 5 Black Point 6 IR 221 33 909 La Loche Southend IR 200 Peter 221 Ballantyne Cree Garson Lake 49 956 4 30 Bear Creek 22 Whitesand Dam IR 193A 102 155 Birch Narrows Brabant Lake IR 223 La Loche ABOVE 60 Landing Michel 20 CANAM IR 192D HIGHWAY Dillon IR 192C IR 194 English River Dipper Lake 110 IR 193 Buffalo English River McLennan Lake 6 Birch Narrows Patuanak NORMAL River Dene Buffalo Narrows Primeau LakeIR 192B St.George's Hill 3 IR 192F English River English River IR 192A English River 11 Elak Dase 102 925 Laonil Lake / Seabee Mine 53 11 33 6 IR 219 Lac la Ronge 92 Missinipe Grandmother’s -

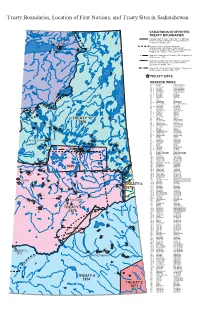

Treaty Boundaries Map for Saskatchewan

Treaty Boundaries, Location of First Nations, and Treaty Sites in Saskatchewan VARIATIONS IN DEPICTED TREATY BOUNDARIES Canada Indian Treaties. Wall map. The National Atlas of Canada, 5th Edition. Energy, Mines and 229 Fond du Lac Resources Canada, 1991. 227 General Location of Indian Reserves, 225 226 Saskatchewan. Wall Map. Prepared for the 233 228 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs by Prairie 231 224 Mapping Ltd., Regina. 1978, updated 1981. 232 Map of the Dominion of Canada, 1908. Department of the Interior, 1908. Map Shewing Mounted Police Stations...during the Year 1888 also Boundaries of Indian Treaties... Dominion of Canada, 1888. Map of Part of the North West Territory. Department of the Interior, 31st December, 1877. 220 TREATY SITES RESERVE INDEX NO. NAME FIRST NATION 20 Cumberland Cumberland House 20 A Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 B Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 C Muskeg River Cumberland House 20 D Budd's Point Cumberland House 192G 27 A Carrot River The Pas 28 A Shoal Lake Shoal Lake 29 Red Earth Red Earth 29 A Carrot River Red Earth 64 Cote Cote 65 The Key Key 66 Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 66 A Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 68 Pheasant Rump Pheasant Rump Nakota 69 Ocean Man Ocean Man 69 A-I Ocean Man Ocean Man 70 White Bear White Bear 71 Ochapowace Ochapowace 222 72 Kahkewistahaw Kahkewistahaw 73 Cowessess Cowessess 74 B Little Bone Sakimay 74 Sakimay Sakimay 74 A Shesheep Sakimay 221 193B 74 C Minoahchak Sakimay 200 75 Piapot Piapot TREATY 10 76 Assiniboine Carry the Kettle 78 Standing Buffalo Standing Buffalo 79 Pasqua -

Ressources Naturelles Canada

111° 110° 109° 108° 107° 106° 105° 104° 103° 102° 101° 100° 99° 98° n Northwest Territories a i d n i a r i e Territoires du Nord-Ouest d M i n r a e h i Nunavut t M 60° d r 60° i u r d o e n F M o c e d S r 1 i 2 h 6 23 2 2 T 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 126 12 11 10 9 Sovereign 4 3 2 125 8 7 6 5 4 3 9 8 7 6 5 Thainka Lake 23 Lake 19 18 17 16 15 13 12 11 10 Tazin Lake Ena Lake Premier 125 124 125 Lake Selwyn Lake Ressources naturelles Sc ott Lake Dodge Lake 124 123 Tsalwor Lake Canada 124 Misaw Lake Oman Fontaine Grolier Bonokoski L. 123 1 Harper Lake Lake 22 Lake 123 Lake Herbert L. Young L. CANADA LANDS - SASKATCHEWAN TERRES DU CANADA – SASKATCHEWAN 122 Uranium City Astrolabe Lake FIRST NATION LANDS and TERRES DES PREMIÈRES NATIONS et 121 122 Bompas L. Beaverlodge Lake NATIONAL PARKS OF CANADA PARCS NATIONAUX DU CANADA 121 120 121 Fond du Lac 229 Thicke Lake Milton Lake Nunim Lake 120 Scale 1: 1 000 000 or one centimetre represents 10 kilometres Chipman L. Franklin Lake 119 120 Échelle de 1/1 000 000 – un centimètre représente 10 kilomètres Fond du Lac 227 119 0 12.5 25 50 75 100 125 150 1 Lake Athabasca 18 Fond-du-Lac ! 119 Chicken 225 Kohn Lake Fond du Lac km 8 Fond du Lac 228 Stony Rapids 11 117 ! Universal Transverse Mercator Projection (NAD 83), Zone 13 233 118 Chicken 226 Phelps Black Lake Lake Projection de Mercator transverse universelle (NAD 83), zone 13 Fond du Lac 231 117 116 Richards Lake 59° 59° 117 Chicken NOTE: Ath 224 This map is an index to First Nation Lands (Indian Lands as defined by the Indian Act) abasca Sand Dunes Fond du Lac 232 Provincial Wilderne Black Lake 116 1 ss Park and National Parks of Canada. -

Health Status Report Chapter 4: Community Well Being

July 2017 Health Status Report 2015 - 2010 Community Well Being 1 of 11 Suggested Citation: Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority. Health Status Report 2010-2015: Community Well-being. Public Health Unit, Prince Albert, 2017. Available at: www.nitha.com 2 of 11 Chapter 4: Community Well-being Table of Contents Key Findings: ................................................................................................................................ 4 Background: .................................................................................................................................. 5 Results: .......................................................................................................................................... 5 CWB (Community Well-Being) Index Scores ............................................................................. 5 INCOME ...................................................................................................................................... 7 EDUCATION ............................................................................................................................... 8 HOUSING .................................................................................................................................... 9 LABOUR FORCE ACTIVITY .................................................................................................... 10 Discussion: ................................................................................................................................. -

Saskatchewan Official Road

PRINCE ALBERT MELFORT MEADOW LAKE Population MEADOW LAKE PROVINCIAL PARK Population 35,926 Population 40 km 5,992 5,344 Prince Albert Visitor Information Centre Visitor Information 4 3700 - 2nd Avenue West Prince Albert National Park / Waskesieu Nipawin 142 km Northern Lights Palace Meadow Lake Tourist Information Centre Phone: 306-682-0094 La Ronge 88 km Choiceland and Hanson Lake Road Open seasonally 110 Mcleod Avenue W 79 km Hwy 4 and 9th Ave W GREEN LAKE 239 km 55 Phone: 306-752-7200 Phone: 306-236-4447 ve E 49 km Flin Flon t A Chamber of Commerce 6 RCMP 1s 425 km Open year-round 2nd Ave W 3700 - 2nd Avenue West t r S P.O. Phone: 306-764-6222 3 e iv M e R 5th Ave W r e Prince Albert . t Open year-round e l e n c f E v o W ru e t p 95 km r A 7th Ave W t S C S t y S d Airport 3 Km 9th Ave W H a 5 r w 3 Little Red 55 d ? R North Battleford T River Park a Meadow Lake C CANAM o Radio Stations: r HIGHWAY Lions Regional Park 208 km 15th St. N.W. 15th St. N.E. Veteran’s Way B McDonald Ave. C CJNS-Q98-FM e RCMP v 3 Mall r 55 . A e 3 e Meadow Lake h h v RCMP ek t St. t 5 km Northern 5 A Golf Club 8 AN P W Lights H ark . E Airport e e H Ave. -

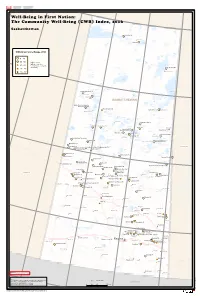

The Community Well-Being (CWB) Index, 2016

117° W 114° W 111° W 108° W 105° W 102° W Well-Being in First Nation: The Community Well-Being (CWB) Index, 2016 Selwyn N Lake ° 0 Saskatchewan 6 Misaw Lake Lake Athabasca F¸ ond du Lac 227 Stony Rapids ! ¸ Chicken 224 Black Lake Phelps Lake CWB Index Score Range, 2016 Charcoal Lake Hatchet Lake ¸ 0 - 49 Pasfield ¸ Lake Theriau N 50 - 59 ° Higher scores Lake 7 5 indicate a greater Waterbury Wollaston Lake ! Lake · 60 - 69 level of socio-economic well-being. ¸ Lac La Hache 220 ^ 70 - 79 ^ !P ^^ 80 - 100 Wollaston Lake Lloyd Lake Cree Lake Careen Lake Black Birch Wasekamio Lake Lake Highrock Reindeer Lake Clearwa¸ ter River Dene 222 Lake Turnor Lake Wathaman !P Upper Lake La Loche ¸ Foster Lac Lake La Loche Frobisher Lake N Turnor Lake Nokomis ° Lake 7 5 193B Oliver Lake SASKATCHEWAN Davin Lake Deception Lake Buffalo River Dene Nation 193 (Peter Pond Lake¸ 193) Churchill Macoun Lake Lake ¸ Wapachewunak 192D ¸ !P ! Southend No. 200A Southend 200 · Primeau Lake Buffalo Narrows Dipper C Lac h Lake u r Île- c h à-la- il l R Crosse Brabant iv e Lake r Knee Lake Pinehouse Lake Sandfly Lake McIntosh Steephill Lake Black Bear Lake Kazan Island Lake Lake Île-à-la-Crosse !P Pinehouse P ! ¸ Besnard Grandmother's Bay 219 Lake Canoe Lake Mountain ¸ Canoe Lake 165 La ¸ Plonge 192 Nemeiben Lake Lake Chu rchill River Arsenault ¸ Stanley 157 ¸ Primrose Lake Sandy Bay Lake Sucker River 156C ¸ !P Keeley Lac la (Nemebien River 156C) Wapaskokimaw 202 Lake Plonge ¸ Trade Lake Lac la Ronge Kipahigin N Morin Lake 217 ¸ Lake ° ¸ 4 Kitsakie 156B Wood 5 Egg !P Lake -

Saskatchewan Tire Collection Zones

Legend Saskatchewan 0255075 Tire Zones First Nation Reserve Highway Kilometres Tire Collection Zones Urban Municipality Park R.M. Water Creation Date 01/13/2018 Version 1.0 Mahigan UV165 Oskikebuk Lake MISTIK 184 106 Lake 203 UV Map 1 of 1 WASKWAYNIKAPIK Lake Vance 228 Wildfong Annabel 919 Dore Lake Bryans Lake UV Casat 911 Lake UVViney Lake Lake Lake Lake NAKISKATOWANEEK 227 Neagle FLIN FLON 165 Lake UV CREIGHTON Flotten UV903 Sarginson MCKAY IM Lake Lake 209 PISIWIMINIWAT Hanson Smoothstone 207 Lake Lake Deschambault NARE BEACH DORE 106 DE Waterhen LAK 912 MUSKWAMINIWATIM Lake UV E UV Chisholm Spectral 924 Limestone Shuttleworth UV 225 Lake UV2 Lake Lake Lake McNally Lake W ATERHEN UV969 AMISK Lake Hollingdale 130 Stringer LAKE M Beaupre 916 Lake EADOW UV Lake 184 BI LA Lake Molanosa Cobb Kerr G KE GREIG L 167 IS AKE UV 21 LAND PROVINCIA UV155 Lake Lake Hobbs Lake Amisk UV G L SO OO UT PIE DSOIL H Sled Clarke Lake Lake Nepe RCELA PAR WATERH GLADUE Edgelow ND K EN Lake Lake Oatway Balsam Lake LAKE LAKE Lake Meeyomoot Shallow Renown Lake Lake Maraiche 105 SLED Lake UV55 Nipekamew Lake Lake Lake DORIN L Lake Saskoba 622 TOSH AKE Lake WEYAKWIN Big Sandy Harrington AMISKOSAKAHIKAN Wanner Lake Narrow Herman Lake 210 Lake Lake Goulden Lake Lake UV924 East Trout Saunders GRE Lake Lake Suggi Windy EN Montre 26 4 al 927 UV106 Lake Lake UV UV LAK Lake UV Little Bear E Lake Leonard STURGEON WEIR Marquis Lake 184 Lake Red Bobs T 55 CLARENCE-STEEPBANK Waterfall HUNDERCHILD FLYING DUST UV Lake O'Leary Lake 115 UV55 105 LAKES PROVINCIAL PARK Lake Namew -

Environmental and Municipal Management Services Administrative Boundaries

ENVIRONMENTAL AND MUNICIPAL MANAGEMENT SERVICES ADMINISTRATIVE BOUNDARIES R n i z a T Patterson Sovereign Selwyn Lake Thainka Scott Bailey Lake r Lake Lake Wayaw Ena e Misaw Lake v Lake i Hamill Picea Lake Lake R Warren Tazin Prem Lake Lake ier Lake Tsalwor er Lake Tazin Riv Lake Robins Gebhard Lake Lake Dodge Lake Lake Harper Lake Keseechewun Many Oldman Lake LEGEND Lak River Bonokoski e CAMSELL Lake Oman Islands Fontaine Grollier Wapiyao Lake PORTAGE L Hawkins Nicholson ake Astrolabe Lake Lake Lake Lake ke " URANIUM Lake La Lake Emerson ipuyew CITY Forsyth Bompas Herbert Ap ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS Lake ake Beaverlodge e Young ake L " Lake s Lake L CITY 962 Box a r e Lake e n r v a Nevins Lake i Lake G R m d Lake Kaskawan Nunim Black l O Thicke Lake ke S Milton La Gravelbourg pring Pt Bay Lake Grove " I.R.229 B Lake J" u Lake Fond Du Lac l ew son TOWN y Mukas Hutcher e Maur a Franklin ice Pt Clut Chipman Charlebois Walker Lake Lake Johnston R Lake iver Lakes Lake Lake e Lake Island I.R.227 in Hewgill p inkham Kindersley dFond Du Lac cu P Fon Du or Lake I.R.228 L P Lake ! Fond Du Lac ac River Kohn VILLAGE LAKE ATH I.R.233 I.R.225 Fanson ABASCA Fond Du Lac Chicken Lake chak Helmer O Lake Phelps William Pt Black ake Lake Richards l Lake r I.R.224 e I.R.226 Meadow Lake 905 Chicken v i Lake Lake Chicken R I.R.232 Elizabeth " Fond Misekumaw ah I.R.231 Hann ra Du Lac Riou Falls Newnham Ha NORTHERN SETTLEMENT Fond Du Lac r Lake h e Lake Lake ne Engler erc Lake iv A la Lake P R rchibald ar tt O urne cF Lake Bickerton B La a t ke M h Hocking Nordbye -

Lloydminster, AB BEAUVAL BREYNAT JANS BAY 965 Regional Municipality

Lloydminster, AB BEAUVAL BREYNAT JANS BAY 965 Regional Municipality Secondary Highways 123 HEART LAKE INDIAN RESERVE 167 Primary Highways 123 813 2 Express Way 123 858 Par Boundary ISLAND LAKE SOUTH ISLAND LAKE PLAMONDON WEST BAPTISTE LAC LA BICHE Cities 250000 and AboveCity SUNSET BEACH WHITE GULL 663 Cities 1 - 249999 City ATHABASCA HYLO 155 904 Cities 0 - 0 City CASLAN BEAVER LAKE INDIAN RESERVE 131 COLINTON DORE LAKE BOYLE BONDISS LAKELAND COUNTY COLD LAKE INDIAN RESERVE 149B WATERHEN LAKE 827 WATERHEN 130 866 COLD LAKE INDIAN RESERVE 149A LARKSPUR KIKINO LA COREY 55 GREIG LAKE 63 BIG HEAD 124 224 924 ROCHESTER PIERCELAND DAPP 661 MCRAE 881 ARDMORE 28 DORINTOSH NEWBROOK FORT KENT 55 TAWATINAW COLD LAKE INDIAN RESERVE 149 GREEN LAKE 44 855 660 NESTOW ABEE 897 MALLAIG 4 BONNYVILLE BEACH MINISTIKWAN 161A SPEDDEN ST VINCENT 831 BELLIS RAPID VIEW 18 657 FLYING DUST FIRST NATION 105 CLYDE VIMY HORSESHOE BAY KEHIWIN INDIAN RESERVE 123 EAGLES LAKE 165C RADWAY MAKWA LAKE 129C 799 SADDLE LAKE WHELAN 55 OPAL ST PAUL MAKWA LAKE 129 2 PUSKIAKIWENIN INDIAN RESERVE 122 BUSBY REDWATER 652 MAKWA 651 SPUTINOW LEGAL BARTHEL 943 ALCOMDALE ELK POINT 38 45 ANDREW LAFOND UNIPOUHEOS INDIAN RESERVE 121 STAR WILLINGDON FROG LAKE 21 945 MORINVILLE WOSTOK 646 4 GIBBONS BROSSEAU THUNDERCHILD FIRST NATION 115D 28 HAIRY HILL 637 881 CHITEK LAKE FORT SASKATCHEWAN MUSIDORA 41 SEEKASKOOTCH 119 37 NAMAO TWO HILLS BRIGHT SAND DERWENT MAKAOO INDIAN RESERVE 120 HILLIARD 857 830 BEAUVALLON 795 THUNDERCHILD FIRST NATION 115C LEOVILLE 797 PELICAN LAKE 191B 45 DEWBERRY KIVIMAA-MOONLIGHT -

Saskatchewan Population Report 2016 Census of Canada

Saskatchewan Population Report 2016 Census of Canada 2016 CENSUS POPULATION Saskatchewan’s Census population for 2016 Villages and Resort Villages accounted for was 1,098,352, according to Statistics Canada. This represents an increase of 64,971 persons 47,308 persons in 2016. This is an increase of 228 persons (0.5 percent) from the 2011 village (6.3 percent) from the 2011 Census population of 1,033,381. and resort village population of 47,080. These people live in a total of 21,159 dwellings. Table 1 shows the Census population counts Indian Reserves also decreased in population and growth rates for Saskatchewan for the past between 2011 and 2016. Reserve population 55 years. fell by 172 persons (0.3 percent) to 56,050 in 2016 from 56,222 in 2011. These people live in Table 1: Census Population, 1961 - 2016 a total of 13,995 dwellings. Saskatchewan Rural Municipality population increased by Date Census Population Growth Rate 1,934 to 176,535 persons in 2016 from 174,601 1961 925,181 5.1% persons in 2011. This represents an increase of 1966 955,344 3.3% 1.1 percent. These people live in a total of 1971 926,242 -3.0% 65,770 dwellings. 1976 921,323 -0.5% 1981 968,313 5.1% Northern Villages, Hamlets, Crown Colonies, 1986 1,009,613 4.3% Unorganized and other populations fell 1,201 1991 988,928 -2.0% persons between 2011 and 2016 from 14,630 1996 990,237 0.1% persons to 13,429 persons. These people live in 2001 978,933 -1.1% a total of 4,183 dwellings. -

Provincial Composite

0 25 50 75 Saskatchewan S E Kilometres I Provincial C N Creation Date E E Electoral U C 01/10/2020 T I N Legend Version 1.3 I COMPOSITE Constituency T V S ² O N Constituency First Nation Reserve Highway R O P C This map is a graphic representation of N F Saskatchewan provincial constituencies to be I Urban Municipality Park Saskatchewan constituency boundaries are drawn in accordance with The represented by elected members of the O Representation Act, 2012 and any amendments thereto. These maps have been H Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan. The produced solely for the purpose of identifying polling divisions within each constituency. T N I Water boundaries of these constituencies are for the O Source data has been adapted from Information Services Corporation of Saskatchewan, W I 28th and 29th General Election. Provincial Sask Cadastral (Surface) dataset and administrative overlays. Reproduced with the T permission of Information Services Corporation of Saskatchewan. A C All data captured on this map is current as of the retrieval date of January 2019, unless otherwise stated. Composite O L Map 1 of 1 110°W 109° W 108°W 102°W 107°W 106°W 105°W 104°W 103°W s Dionne Collins Hatle Combre Thainka Scott Lake Ena Selwyn Lake Lake Lake Lake ake Lake Sovereign L Lake Hamill Lake isaw Picea Robins Alley Lake M Lake Lake Lake Lake Wayow Gebhard Lake Lake Bailey Tazin Premier Hamden Lake Lake Lake Lake Saruk Patterson Tsalwor Dodge Lake Lake Lake Lake Polgreen Lake Anson Middlemiss Lake Keseechewun Harper Taché Lake Many Islands Oldman Bonokoski