PMS 52 Spring 1995 PMS 52

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Noir Timeline Compiled from Data from the Internet Movie Database—412 Films

Film Noir Timeline Compiled from data from The Internet Movie Database—412 films. 1927 Underworld 1944 Double Indemnity 1928 Racket, The 1944 Guest in the House 1929 Thunderbolt 1945 Leave Her to Heaven 1931 City Streets 1945 Scarlet Street 1932 Beast of the City, The 1945 Spellbound 1932 I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang 1945 Strange Affair of Uncle Harry, The 1934 Midnight 1945 Strange Illusion 1935 Scoundrel, The 1945 Lost Weekend, The 1935 Bordertown 1945 Woman in the Window, The 1935 Glass Key, The 1945 Mildred Pierce 1936 Fury 1945 My Name Is Julia Ross 1937 You Only Live Once 1945 Lady on a Train 1940 Letter, The 1945 Woman in the Window, The 1940 Stranger on the Third Floor 1945 Conflict 1940 City for Conquest 1945 Cornered 1940 City of Chance 1945 Danger Signal 1940 Girl in 313 1945 Detour 1941 Shanghai Gesture, The 1945 Bewitched 1941 Suspicion 1945 Escape in the Fog 1941 Maltese Falcon, The 1945 Fallen Angel 1941 Out of the Fog 1945 Apology for Murder 1941 High Sierra 1945 House on 92nd Street, The 1941 Among the Living 1945 Johnny Angel 1941 I Wake Up Screaming 1946 Shadow of a Woman 1942 Sealed Lips 1946 Shock 1942 Street of Chance 1946 So Dark the Night 1942 This Gun for Hire 1946 Somewhere in the Night 1942 Fingers at the Window 1946 Locket, The 1942 Glass Key, The 1946 Strange Love of Martha Ivers, The 1942 Grand Central Murder 1946 Strange Triangle 1942 Johnny Eager 1946 Stranger, The 1942 Journey Into Fear 1946 Suspense 1943 Shadow of a Doubt 1946 Tomorrow Is Forever 1943 Fallen Sparrow, The 1946 Undercurrent 1944 When -

Youth Clarence Brown Theatre Clarence Brown Theatre

YOUTH CLARENCE BROWN THEATRE CLARENCE BROWN THEATRE he Clarence Brown Theatre Company is a professional theatre company in residence at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Founded in 1974 by Sir Anthony Quayle and Dr. Ralph G. Allen, the company is a member Tof the League of Resident Theatres (LORT) and is the only professional LORT company within a 150-mile radius of Knoxville. The University of Tennessee is one of a select number of universities nationwide that are affiliated with a professional LORT theatre, allowing students regular opportunities to work alongside professional actors, directors, designers, dramaturgs, and production artists. The theatre was named in honor of Knoxville native and University of Tennessee graduate, Clarence Brown, the distinguished MGM director of such beloved films as “The Yearling” and “National Velvet”. In addition to the 575-seat proscenium theatre, the CBT’s facilities house the costume shop, electrics department, scene shop, property shop, actors’ dressing quarters, and a 100-seat Lab Theatre. The Clarence Brown Theatre Company also utilizes the Ula Love Doughty Carousel Theatre, an arena theatre with flexible seating for 350, located next to the CBT on the University of Tennessee campus. The Clarence Brown Theatre has a 19-member resident faculty, headed by Calvin MacLean, and 25 full-time management and production staff members. SEASON FOR YOUTH t the Clarence Brown Theatre, we recognize the positive impact that the performing arts have on young people. We are pleased to continue our commitment to providing high-quality theatre for young audiences Awith our 2013-2014 Season for Youth performances. -

The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Film Studies (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-2021 The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Michael Chian Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/film_studies_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chian, Michael. "The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood." Master's thesis, Chapman University, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000269 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film Studies (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood A Thesis by Michael Chian Chapman University Orange, CA Dodge College of Film and Media Arts Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Film Studies May, 2021 Committee in charge: Emily Carman, Ph.D., Chair Nam Lee, Ph.D. Federico Paccihoni, Ph.D. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Copyright © 2021 by Michael Chian III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor and thesis chair, Dr. Emily Carman, for both overseeing and advising me throughout the development of my thesis. Her guidance helped me to both formulate better arguments and hone my skills as a writer and academic. I would next like to thank my first reader, Dr. Nam Lee, who helped teach me the proper steps in conducting research and recognize areas of my thesis to improve or emphasize. -

The Naked Spur: Classic Western Scores from M-G-M

FSMCD Vol. 11, No. 7 The Naked Spur: Classic Western Scores From M-G-M Supplemental Liner Notes Contents The Naked Spur 1 The Wild North 5 The Last Hunt 9 Devil’s Doorway 14 Escape From Fort Bravo 18 Liner notes ©2008 Film Score Monthly, 6311 Romaine Street, Suite 7109, Hollywood CA 90038. These notes may be printed or archived electronically for personal use only. For a complete catalog of all FSM releases, please visit: http://www.filmscoremonthly.com The Naked Spur ©1953 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. The Wild North ©1952 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. The Last Hunt ©1956 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. Devil’s Doorway ©1950 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. Escape From Fort Bravo ©1953 Turner Entertainment Co., A Warner Bros. Entertainment Company. All rights reserved. FSMCD Vol. 11, No. 7 • Classic Western Scores From M-G-M • Supplemental Liner Notes The Naked Spur Anthony Mann (1906–1967) directed films in a screenplay” and The Hollywood Reporter calling it wide variety of genres, from film noir to musical to “finely acted,” although Variety felt that it was “proba- biopic to historical epic, but today he is most often ac- bly too raw and brutal for some theatergoers.” William claimed for the “psychological” westerns he made with Mellor’s Technicolor cinematography of the scenic Col- star James Stewart, including Winchester ’73 (1950), orado locations received particular praise, although Bend of the River (1952), The Far Country (1954) and The several critics commented on the anachronistic appear- Man From Laramie (1955). -

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present A film by Craig McCall Worldwide Sales: High Point Media Group Contact in Cannes: Residences du Grand Hotel, Cormoran II, 3 rd Floor: Tel: +33 (0) 4 93 38 05 87 London Contact: Tel: +44 20 7424 6870. Fax +44 20 7435 3281 [email protected] CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 1 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff www.jackcardiff.com Contents: - Film Synopsis p 3 - 10 Facts About Jack p 4 - Jack Cardiff Filmography p 5 - Quotes about Jack p 6 - Director’s Notes p 7 - Interviewee’s p 8 - Bio’s of Key Crew p10 - Director's Q&A p14 - Credits p 19 CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 2 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN : The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff A Documentary Feature Film Logline: Celebrating the remarkable nine decade career of legendary cinematographer, Jack Cardiff, who provided the canvas for classics like The Red Shoes and The African Queen . Short Synopsis: Jack Cardiff’s career spanned an incredible nine of moving picture’s first ten decades and his work behind the camera altered the look of films forever through his use of Technicolor photography. Craig McCall’s passionate film about the legendary cinematographer reveals a unique figure in British and international cinema. Long Synopsis: Cameraman illuminates a unique figure in British and international cinema, Jack Cardiff, a man whose life and career are inextricably interwoven with the history of cinema spanning nine decades of moving pictures' ten. -

The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir

1 Murder, Mugs, Molls, Marriage: The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir Noir is a conversation rather than a single genre or style, though it does have a history, a complex of overlapping styles and typical plots, and more central directors and films. It is also a conversation about its more common philosophies, socio-economic and sexual concerns, and more expansively its social imaginaries. MacIntyre's three rival versions suggest the different ways noir can be studied. Tradition's approach explains better the failure of the other two, as will as their more limited successes. Something like the Thomist understanding of people pursuing perceived (but faulty) goods better explains the neo- Marxist (or other power/conflict) model and the self-construction model. Each is dependent upon the materials of an earlier tradition to advance its claims/interpretations. [Styles-studio versus on location; expressionist versus classical three-point lighting; low-key versus high lighting; whites/blacks versus grays; depth versus flat; theatrical versus pseudo-documentary; variety of felt threat levels—investigative; detective, procedural, etc.; basic trust in ability to restore safety and order versus various pictures of unopposable corruption to a more systemic nihilism; melodramatic vs. colder, more distant; dialogue—more or less wordy, more or less contrived, more or less realistic; musical score—how much it guides and dictates emotions; presence or absence of humor, sentiment, romance, healthy family life; narrator, narratival flashback; motives for criminality and violence-- socio- economic (expressed by criminal with or without irony), moral corruption (greed, desire for power), psychological pathology; cinematography—classical vs. -

Feel Films / Resen «Cine Clásico Exclusivamente En

JOAN CRAWFORD EN ASÍ AMA LA MUJER vamente. La gran mayoría de sus films en MGM (SADIE MCKEE) (V.O.S.). UNA PELÍCULA durante la década de 1930, que representan el DE CLARENCE BROWN cénit de su éxito, belleza y popularidad, ni Título: Así ama la mujer siquiera llegaron a estrenarse en España. Los Distribuidora: Feel Films / Resen «Cine motivos de esta omisión son diversos, pero po- Clásico Exclusivamente en V.O.S.» drían resumirse en uno: Crawford fue en esencia Zona: 2 una estrella y un fenómeno 100% norteameri- Contenido: Un disco cano. Formato de imagen: 4:3 / 1.33:1 Sadie McKee no es ninguna excepción a este Audio: Dolby Digital Mono inglés respecto, si bien se constituye como una de las Subtítulos: castellano, portugués cintas más significativas de la segunda parte de Contenido extra: tráiler original su filmografía, ya en la época sonora. La actriz Precio: 15,65 € ingresó en el celuloide, contratada por MGM, en 1925. Tras una serie de pequeñas apariciones, el estudio decidió lanzarla en 1928 como la quin- taesencia de la modernidad, interpretando a la flapper propia de los años 20. El hundimiento de la bolsa de Wall Street en 1929 sumió al país en el desempleo, la pobreza y el hambre, y tanto MGM como la estrella comprendieron que se había acabado la etapa de la «virgen moderna». Debía crearse para ella otro tipo de personalidad, acorde con los nuevos tiempos de la Depresión: la working girl (chica trabajadora), personaje inspirado en su biografía personal y orígenes sociales humildes. El film que inauguró esta ten- dencia fue Amor -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten Through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jensen, Joni Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 21:33:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193556 A COMPARISON OF ORIGINS AND INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND BRITTEN THROUGH ANALYSIS OF THEIR FESTIVAL TE DEUMS by Joni Lynn Jensen Copyright © Joni Lynn Jensen 2005 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Joni Lynn Jensen entitled A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughan Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Josef Knott Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Alban Berg's Filmic Music

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula Dawn, "Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2351. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2351 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ALBAN BERG’S FILMIC MUSIC: INTENTIONS AND EXTENSIONS OF THE FILM MUSIC INTERLUDE IN THE OPERA LULU A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts by Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith A.B., Smith College, 1993 A.M., Smith College, 1995 M.L.I.S., Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 1999 May 2002 ©Copyright 2002 Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to express gratitude to my wonderful committee for working so well together and for their suggestions and encouragement. I am especially grateful to Jan Herlinger, my dissertation advisor, for his insightful guidance, care and precision in editing my written prose and translations, and open mindedness. -

Glorious Technicolor: from George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 the G

Glorious Technicolor: From George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 The Garden of Allah. 1936. USA. Directed by Richard Boleslawski. Screenplay by W.P. Lipscomb, Lynn Riggs, based on the novel by Robert Hichens. With Marlene Dietrich, Charles Boyer, Basil Rathbone, Joseph Schildkraut. 35mm restoration by The Museum of Modern Art, with support from the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation; courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 75 min. La Cucaracha. 1934. Directed by Lloyd Corrigan. With Steffi Duna, Don Alvarado, Paul Porcasi, Eduardo Durant’s Rhumba Band. Courtesy George Eastman House (35mm dye-transfer print on June 5); and UCLA Film & Television Archive (restored 35mm print on July 21). 20 min. [John Barrymore Technicolor Test for Hamlet]. 1933. USA. Pioneer Pictures. 35mm print from The Museum of Modern Art. 5 min. 7:00 The Wizard of Oz. 1939. USA. Directed by Victor Fleming. Screenplay by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, Edgar Allan Woolf, based on the book by L. Frank Baum. Music by Harold Arlen, E.Y. Harburg. With Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke. 35mm print from George Eastman House; courtesy Warner Bros. 102 min. Saturday, June 6 2:30 THE DAWN OF TECHNICOLOR: THE SILENT ERA *Special Guest Appearances: James Layton and David Pierce, authors of The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (George Eastman House, 2015). James Layton and David Pierce illustrate Technicolor’s origins during the silent film era. Before Technicolor achieved success in the 1930s, the company had to overcome countless technical challenges and persuade cost-conscious producers that color was worth the extra effort and expense. -

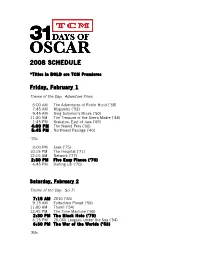

2008 Schedule

2008 SCHEDULE *Titles in BOLD are TCM Premieres Friday, February 1 Theme of the Day: Adventure Films 6:00 AM The Adventures of Robin Hood (’38) 7:45 AM Mogambo (’53) 9:45 AM King Solomon’s Mines (’50) 11:30 AM The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (’48) 1:45 PM Krakatoa, East of Java (’69) 4:00 PM The Naked Prey (’66) 5:45 PM Northwest Passage (’40) ‘70s 8:00 PM Jaws (’75) 10:15 PM The Hospital (’71) 12:15 AM Network (’77) 2:30 PM Five Easy Pieces (’70) 4:45 PM Darling Lili (’70) Saturday, February 2 Theme of the Day: Sci Fi 7:15 AM 2010 (’84) 9:15 AM Forbidden Planet (’56) 11:00 AM Them! (’54) 12:45 PM The Time Machine (’60) 2:30 PM The Black Hole (’79) 4:15 PM 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (’54) 6:30 PM The War of the Worlds (’53) ‘80s 8:00 PM Gandhi (’82) 11:15 PM Atlantic City (’81) 1:15 AM The Trip to Bountiful (’85) 3:15 AM Mephisto (’82) Sunday, February 3 Theme of the Day: Musicals 6:00 AM Anchors Aweigh (’45) 8:30 AM Brigadoon (’54) 10:30 AM The Harvey Girls (’46) 12:15 PM The Band Wagon (’53) 2:15 PM Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (’54) 4:00 PM Gigi (’58) 6:00 PM An American in Paris (’51) ‘90s/’00s 8:00 PM Sense and Sensibility (’95) 10:30 PM Quiz Show (’94) 12:45 PM Kundun (’97) 3:15 AM The Wings of the Dove (’97) Monday, February 4 Theme of the Day: Biopics 5:30 AM The Story of Louis Pasteur (’35) 7:00 AM The Life of Emile Zola (’37) 9:00 AM The Adventures of Mark Twain (’44) 11:15 AM The Eddy Duchin Story (’56) 1:30 PM The Joker is Wild (’57) 3:45 PM Night and Day (’46) 6:00 PM The Glenn Miller Story (’54) ‘20s/’30s 8:00 PM Wings