Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Variable Star Classification and Light Curves Manual

Variable Star Classification and Light Curves An AAVSO course for the Carolyn Hurless Online Institute for Continuing Education in Astronomy (CHOICE) This is copyrighted material meant only for official enrollees in this online course. Do not share this document with others. Please do not quote from it without prior permission from the AAVSO. Table of Contents Course Description and Requirements for Completion Chapter One- 1. Introduction . What are variable stars? . The first known variable stars 2. Variable Star Names . Constellation names . Greek letters (Bayer letters) . GCVS naming scheme . Other naming conventions . Naming variable star types 3. The Main Types of variability Extrinsic . Eclipsing . Rotating . Microlensing Intrinsic . Pulsating . Eruptive . Cataclysmic . X-Ray 4. The Variability Tree Chapter Two- 1. Rotating Variables . The Sun . BY Dra stars . RS CVn stars . Rotating ellipsoidal variables 2. Eclipsing Variables . EA . EB . EW . EP . Roche Lobes 1 Chapter Three- 1. Pulsating Variables . Classical Cepheids . Type II Cepheids . RV Tau stars . Delta Sct stars . RR Lyr stars . Miras . Semi-regular stars 2. Eruptive Variables . Young Stellar Objects . T Tau stars . FUOrs . EXOrs . UXOrs . UV Cet stars . Gamma Cas stars . S Dor stars . R CrB stars Chapter Four- 1. Cataclysmic Variables . Dwarf Novae . Novae . Recurrent Novae . Magnetic CVs . Symbiotic Variables . Supernovae 2. Other Variables . Gamma-Ray Bursters . Active Galactic Nuclei 2 Course Description and Requirements for Completion This course is an overview of the types of variable stars most commonly observed by AAVSO observers. We discuss the physical processes behind what makes each type variable and how this is demonstrated in their light curves. Variable star names and nomenclature are placed in a historical context to aid in understanding today’s classification scheme. -

Dust and Molecular Shells in Asymptotic Giant Branch Stars⋆⋆⋆⋆⋆⋆

A&A 545, A56 (2012) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201118150 & c ESO 2012 Astrophysics Dust and molecular shells in asymptotic giant branch stars,, Mid-infrared interferometric observations of R Aquilae, R Aquarii, R Hydrae, W Hydrae, and V Hydrae R. Zhao-Geisler1,2,†, A. Quirrenbach1, R. Köhler1,3, and B. Lopez4 1 Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg (ZAH), Landessternwarte, Königstuhl 12, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 National Taiwan Normal University, Department of Earth Sciences, 88 Sec. 4, Ting-Chou Rd, Wenshan District, Taipei, 11677 Taiwan, ROC 3 Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 4 Laboratoire J.-L. Lagrange, Université de Nice Sophia-Antipolis et Observatoire de la Cˆote d’Azur, BP 4229, 06304 Nice Cedex 4, France Received 26 September 2011 / Accepted 21 June 2012 ABSTRACT Context. Asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars are one of the largest distributors of dust into the interstellar medium. However, the wind formation mechanism and dust condensation sequence leading to the observed high mass-loss rates have not yet been constrained well observationally, in particular for oxygen-rich AGB stars. Aims. The immediate objective in this work is to identify molecules and dust species which are present in the layers above the photosphere, and which have emission and absorption features in the mid-infrared (IR), causing the diameter to vary across the N-band, and are potentially relevant for the wind formation. Methods. Mid-IR (8–13 μm) interferometric data of four oxygen-rich AGB stars (R Aql, R Aqr, R Hya, and W Hya) and one carbon- rich AGB star (V Hya) were obtained with MIDI/VLTI between April 2007 and September 2009. -

Aqueous Alteration on Main Belt Primitive Asteroids: Results from Visible Spectroscopy1

Aqueous alteration on main belt primitive asteroids: results from visible spectroscopy1 S. Fornasier1,2, C. Lantz1,2, M.A. Barucci1, M. Lazzarin3 1 LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, UPMC Univ Paris 06, Univ. Paris Diderot, 5 Place J. Janssen, 92195 Meudon Pricipal Cedex, France 2 Univ. Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cit´e, 4 rue Elsa Morante, 75205 Paris Cedex 13 3 Department of Physics and Astronomy of the University of Padova, Via Marzolo 8 35131 Padova, Italy Submitted to Icarus: November 2013, accepted on 28 January 2014 e-mail: [email protected]; fax: +33145077144; phone: +33145077746 Manuscript pages: 38; Figures: 13 ; Tables: 5 Running head: Aqueous alteration on primitive asteroids Send correspondence to: Sonia Fornasier LESIA-Observatoire de Paris arXiv:1402.0175v1 [astro-ph.EP] 2 Feb 2014 Batiment 17 5, Place Jules Janssen 92195 Meudon Cedex France e-mail: [email protected] 1Based on observations carried out at the European Southern Observatory (ESO), La Silla, Chile, ESO proposals 062.S-0173 and 064.S-0205 (PI M. Lazzarin) Preprint submitted to Elsevier September 27, 2018 fax: +33145077144 phone: +33145077746 2 Aqueous alteration on main belt primitive asteroids: results from visible spectroscopy1 S. Fornasier1,2, C. Lantz1,2, M.A. Barucci1, M. Lazzarin3 Abstract This work focuses on the study of the aqueous alteration process which acted in the main belt and produced hydrated minerals on the altered asteroids. Hydrated minerals have been found mainly on Mars surface, on main belt primitive asteroids and possibly also on few TNOs. These materials have been produced by hydration of pristine anhydrous silicates during the aqueous alteration process, that, to be active, needed the presence of liquid water under low temperature conditions (below 320 K) to chemically alter the minerals. -

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy Special Publications No. 1 George Herbig in 1960 —————————————————————– GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution —————————————————————– Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy University of Hawaii at Manoa 640 North Aohoku Place Hilo, HI 96720 USA . Dedicated to Hannelore Herbig c 2016 by Bo Reipurth Version 1.0 – April 19, 2016 Cover Image: The HH 24 complex in the Lynds 1630 cloud in Orion was discov- ered by Herbig and Kuhi in 1963. This near-infrared HST image shows several collimated Herbig-Haro jets emanating from an embedded multiple system of T Tauri stars. Courtesy Space Telescope Science Institute. This book can be referenced as follows: Reipurth, B. 2016, http://ifa.hawaii.edu/SP1 i FOREWORD I first learned about George Herbig’s work when I was a teenager. I grew up in Denmark in the 1950s, a time when Europe was healing the wounds after the ravages of the Second World War. Already at the age of 7 I had fallen in love with astronomy, but information was very hard to come by in those days, so I scraped together what I could, mainly relying on the local library. At some point I was introduced to the magazine Sky and Telescope, and soon invested my pocket money in a subscription. Every month I would sit at our dining room table with a dictionary and work my way through the latest issue. In one issue I read about Herbig-Haro objects, and I was completely mesmerized that these objects could be signposts of the formation of stars, and I dreamt about some day being able to contribute to this field of study. -

![Arxiv:1905.10588V1 [Astro-Ph.SR]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9865/arxiv-1905-10588v1-astro-ph-sr-1849865.webp)

Arxiv:1905.10588V1 [Astro-Ph.SR]

Draft version May 28, 2019 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX62 TESS Reveals that the Nearby Pisces–Eridanus Stellar Stream is only 120 Myr Old Jason L. Curtis,1, ∗ Marcel A. Agueros¨ ,1 Eric E. Mamajek,2,3 Jason T. Wright,4 and Jeffrey D. Cummings5 1Department of Astronomy, Columbia University, 550 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, USA 2Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, M/S 321-100, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA 3Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY 14627, USA 4Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds, Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, The Pennsylvania State University, 525 Davey Laboratory, University Park, PA 16802, USA 5Center for Astrophysical Sciences, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 N. Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA (Accepted May 24, 2019) Submitted to The Astronomical Journal ABSTRACT Pisces–Eridanus (Psc–Eri), a nearby (d ≃ 80-226 pc) stellar stream stretching across ≈120◦ of the sky, was recently discovered with Gaia data. The stream was claimed to be ≈1 Gyr old, which would make it an exceptional discovery for stellar astrophysics, as star clusters of that age are rare and tend to be distant, limiting their utility as benchmark samples. We test this old age for Psc–Eri in two ways. First, we compare the rotation periods for 101 low-mass members (measured using time series photometry from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, TESS) to those of well-studied open clusters. Second, we identify 34 new high-mass candidate members, including the notable stars λ Tauri (an Algol-type eclipsing binary) and HD 1160 (host to a directly imaged object near the hydrogen- burning limit). -

Ultraviolet Temporal Variability of the Peculiar Star R Aquarii S

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Mathematics, Physics, and Computer Science Science and Technology Faculty Articles and Faculty Articles and Research Research 1995 Ultraviolet Temporal Variability of the Peculiar Star R Aquarii S. R. Meier USN, Research Laboratory Menas Kafatos Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/scs_articles Part of the Instrumentation Commons, and the Stars, Interstellar Medium and the Galaxy Commons Recommended Citation Meier, S.R., Kafatos, M. (1995) Ultraviolet Temporal Variability of the Peculiar Star R Aquarii, Astrophysical Journal, 451: 359-371. doi: 10.1086/176225 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Science and Technology Faculty Articles and Research at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics, Physics, and Computer Science Faculty Articles and Research by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ultraviolet Temporal Variability of the Peculiar Star R Aquarii Comments This article was originally published in Astrophysical Journal, volume 451, in 1995. DOI: 10.1086/176225 Copyright IOP Publishing This article is available at Chapman University Digital Commons: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/scs_articles/139 THE AsTROPHYSICAL JOURNAL, 451:359-371, 1995 September 20 © 1995. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. 1995ApJ...451..359M -

![Arxiv:1709.07265V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 21 Sep 2017 an Der Sternwarte 16, 14482 Potsdam, Germany E-Mail: Jstorm@Aip.De 2 Smitha Subramanian Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4549/arxiv-1709-07265v1-astro-ph-sr-21-sep-2017-an-der-sternwarte-16-14482-potsdam-germany-e-mail-jstorm-aip-de-2-smitha-subramanian-et-al-2324549.webp)

Arxiv:1709.07265V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 21 Sep 2017 an Der Sternwarte 16, 14482 Potsdam, Germany E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Smitha Subramanian Et Al

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Young and Intermediate-age Distance Indicators Smitha Subramanian · Massimo Marengo · Anupam Bhardwaj · Yang Huang · Laura Inno · Akiharu Nakagawa · Jesper Storm Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract Distance measurements beyond geometrical and semi-geometrical meth- ods, rely mainly on standard candles. As the name suggests, these objects have known luminosities by virtue of their intrinsic proprieties and play a major role in our understanding of modern cosmology. The main caveats associated with standard candles are their absolute calibration, contamination of the sample from other sources and systematic uncertainties. The absolute calibration mainly de- S. Subramanian Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics Peking University, Beijing, China E-mail: [email protected] M. Marengo Iowa State University Department of Physics and Astronomy, Ames, IA, USA E-mail: [email protected] A. Bhardwaj European Southern Observatory 85748, Garching, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Yang Huang Department of Astronomy, Kavli Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics, Peking University, Beijing, China E-mail: [email protected] L. Inno Max-Planck-Institut f¨urAstronomy 69117, Heidelberg, Germany E-mail: [email protected] A. Nakagawa Kagoshima University, Faculty of Science Korimoto 1-1-35, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan E-mail: [email protected] J. Storm Leibniz-Institut f¨urAstrophysik Potsdam (AIP) arXiv:1709.07265v1 [astro-ph.SR] 21 Sep 2017 An der Sternwarte 16, 14482 Potsdam, Germany E-mail: [email protected] 2 Smitha Subramanian et al. pends on their chemical composition and age. To understand the impact of these effects on the distance scale, it is essential to develop methods based on differ- ent sample of standard candles. -

R Aquarii: Understanding the Mystery of Its Jets by Model Comparison Michelle Marie Risse Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2009 R Aquarii: Understanding the mystery of its jets by model comparison Michelle Marie Risse Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Risse, Michelle Marie, "R Aquarii: Understanding the mystery of its jets by model comparison" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 10565. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/10565 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. R Aquarii: Understanding the mystery of its jets by model comparison by Michelle Marie Risse A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Astrophysics Program of Study Committee: Lee Anne Willson, Major Professor Steven D. Kawaler Craig A. Ogilvie David B. Wilson Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2009 Copyright c Michelle Marie Risse, 2009. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LISTOFTABLES ................................... iv LISTOFFIGURES .................................. v CHAPTER1. Intent ................................. 1 CHAPTER2. Introduction ............................. 2 2.1 -

The Optical Jet of R Aquarii H

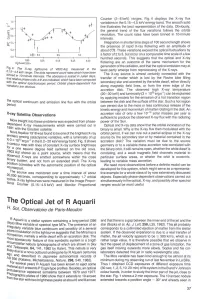

Counter (2-6 keV) ranges. Fig. 4 displays the X-ray flux 1.0 , variations in the 0.15-4.5 keV energy band. The smooth solid VI +t line illustrates the best representation of the data. Obviously, 0.8 ~ + the general trend of the flux variations follows the orbital c: + 15 0.6 + revolution. The count rates have been binned in 10-minute LJ +-f '+-++ + intervals. LJ 0.4 Integration in shorter time steps of 100 second length shows ~ the presence of rapid X-ray flickering with an amplitude of 0.2 I about 0~8. These variations exceed the optical fluctuations by llq,= 0.0 0.5 1.0 a factor of 2 to 3, but occur on a comparable time scale of a few 0.0 hund red seconds. This suggests that the optical and X-ray 0.30 0.35 0.40 0.45 0.50 JO.2444673.00 + flickering are an outcome of the same mechanism for the generation of the radiation, and that the optical emission may at i9 6 . 4: The X-ray lightcurve of V603 Aql, measured in the least partly emerge from reprocessing of the X-rays. t5 4 5 b·. - . keV range. The dots represent count rates which have been The X-ray source is almost certainly connected with the Inned In tO-minute intervals. The abscissa is scaled in Julian days, transfer of matter which is lost by the Roche lobe filling and relative phase units L1 cf) are indicated, which have been computed wlth the optical spectroscopic period. -

I(NASA-CR-154510') ASTEROID SURFACE

REFLECTANCE S PECV A By Michael J. Gaffey Thomas B. McCord (NASA-CR-154510') ASTEROID SURFACE N8-'10992 iMATERIALS: MINERALOGICAL.CHARACTERIZATIONS FROM REFLECTANCE SPECTRA (Hawaii Univ.), 147 p HC -A07/MF A01 CSCL 03B Unclas G , to University of Hawaii at Manoa Institute for Astronomy 2680 Woodlawn Drive * Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Telex: 723-8459 * UHAST HR November 18, 1977 NASA Scientific and Technical Information Facility P.O. Box 8757 Baltimore/Washington Int. Airport Maryland 21240 Gentlemen: RE: Spectroscopy of Asteroids, NSG 7310 Enclosed are two copies of an article entitled "Asteroid Surface Materials: Mineralogical Characterist±cs from Reflectance Spectra," by Dr. Michael J. Gaffey and Dr. Thomas B. McCord, which we have recently submitted for publication to Space Science Reviews. We submit these copies in accordance with the requirements of our NASA grants. Sincerely yours, Thomas B. McCord Principal Investigator TBM:zc Enclosures AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY EMPLOYER ASTEROID SURFACE MATERIALS: MINERALOGICAL CHARACTERIZATIONS FROM REFLECTANCE SPECTRA By Michael J. Gaffey Thomas B. McCord Institute for Astronomy University of Hawaii at Manoa 2680 Woodlawn Drive Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Submitted to Space Science Reviews Publication #151 of the Remote Sensing Laboratory Abstract The interpretation of diagnostic parameters in the spectral reflectance data for asteroids provides a means of characterizing the mineralogy and petrology of asteroid surface materials. An interpretive technique based on a quantitative understanding of the functional relationship between the optical properties of a mineral assemblage and its mineralogy, petrology and chemistry can provide a considerably more sophisticated characterization of a surface material than any matching or classification technique. for those objects bright enough to allow spectral reflectance measurements. -

THE SPECTRUM of RW HYDRAE This Object Offers a Striking

458 ASTRONOMY: SWINGS A ND STR UVE PROC. N. A. S. it is present in the nucleus. [O III] is strong in HD 167362, and very weak in Campbell's star. The striking association in HD 167362 and BD + 300 3639 of a carbon nucleus with a nitrogen envelope suggests that a comparison with NGC 6543 would be interesting, despite the higher excitation prevailing in the nuclear and nebular parts of NGC 6543.11 This object also shows strong nebular lines of [N II], but its nucleus exhibits both N IV and C IV with similar intensities. 1 Astronomy and Astrophysics, 13, 461 (1894). 2 Several excellent spectrograms of Campbell's star (BD + 300 3639) have recently been secured at the McDonald Observatory and agree closely with the description of the spectrum by Wright (Lick Obs. Pub., 13, 220 (1918)); there is no trace of N II, N III, N IV or N V in the nucleus, which is a typical carbon star. 8 Ap. Jour., 2, 354 (1895). 4 Harvard Ann., 76, 31 (1916). 6 Harvard Circ., No. 224 (1921). Henry Draper Catalogue. 7 Harvard Bull., No. 892, 20 (1933). ' Ap. Jour., 61, 389 (1925); 76, 156 (1932). 9"Variable Stars," Harvard Obs. Monograph, No. 5, 311 (1938). 10 Beals has chosen the numbering from WC6 to WC8 so as td allow a certain latitude for new discoveries at either end of the sequence. See Trans. I. A. U., 6, 248 (1938). P. Swings, Ap. Jour. (in press). THE SPECTRUM OF RW HYDRAE By P. SWINGS AND 0. STRUVE MCDONALD OBSERVATORY, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS, AND YERKES OBSERVATORY, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Communicated June 10, 1940 RW Hydrael is an abnormal long-period variable having an unusually small range, of about one magnitude; the maximum photographic magni- tude is 9.7 to 9.9 and the minimum 10.8 to 10.9. -

The Messenger

THE MESSENGER ( , New Meteorite Finds At Imilac No. 47 - March 1987 H. PEDERSEN, ESO, and F. GARe/A, elo ESO Introduction hand, depend more on the preserving some 7,500 meteorites were recovered Stones falling from the sky have been conditions of the terrain, and the extent by Japanese and American expeditions. collected since prehistoric times. They to which it allows meteorites to be spot They come from a smaller, but yet un were, until recently, the only source of ted. Most meteorites are found by known number of independent falls. The extraterrestrial material available for chance. Active searching is, in general, meteorites appear where glaciers are laboratory studies and they remain, too time consuming to be of interest. pressed up towards a mountain range, even in our space age, a valuable However, the blue-ice fields of Antarctis allowing the ice to evaporate. Some source for investigation of the solar sys have proven to be a happy hunting have been Iying in the ice for as much as tem's early history. ground. During the last two decades 700,000 years. It is estimated that, on the average, each square kilometre of the Earth's surface is hit once every million years by a meteorite heavier than 500 grammes. Most are lost in the oceans, or fall in sparsely populated regions. As a result, museums around the world receive as few as about 6 meteorites annually from witnessed falls. Others are due to acci dental finds. These have most often fallen in prehistoric times. Each of the two groups, 'falls' and 'finds', consists of material from about one thousand catalogued, individual meteorites.