Man Vs. Machine a Comparative Study on MIDI Programmed and Recorded Drums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Building Cold War Warriors: Socialization of the Final Cold War Generation

BUILDING COLD WAR WARRIORS: SOCIALIZATION OF THE FINAL COLD WAR GENERATION Steven Robert Bellavia A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Andrew M. Schocket, Advisor Karen B. Guzzo Graduate Faculty Representative Benjamin P. Greene Rebecca J. Mancuso © 2018 Steven Robert Bellavia All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor This dissertation examines the experiences of the final Cold War generation. I define this cohort as a subset of Generation X born between 1965 and 1971. The primary focus of this dissertation is to study the ways this cohort interacted with the three messages found embedded within the Cold War us vs. them binary. These messages included an emphasis on American exceptionalism, a manufactured and heightened fear of World War III, as well as the othering of the Soviet Union and its people. I begin the dissertation in the 1970s, - during the period of détente- where I examine the cohort’s experiences in elementary school. There they learned who was important within the American mythos and the rituals associated with being an American. This is followed by an examination of 1976’s bicentennial celebration, which focuses on not only the planning for the celebration but also specific events designed to fulfill the two prime directives of the celebration. As the 1980s came around not only did the Cold War change but also the cohort entered high school. Within this stage of this cohorts education, where I focus on the textbooks used by the cohort and the ways these textbooks reinforced notions of patriotism and being an American citizen. -

Heavy Metal and Classical Literature

Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 ROCKING THE CANON: HEAVY METAL AND CLASSICAL LITERATURE By Heather L. Lusty University of Nevada, Las Vegas While metalheads around the world embrace the engaging storylines of their favorite songs, the influence of canonical literature on heavy metal musicians does not appear to have garnered much interest from the academic world. This essay considers a wide swath of canonical literature from the Bible through the Science Fiction/Fantasy trend of the 1960s and 70s and presents examples of ways in which musicians adapt historical events, myths, religious themes, and epics into their own contemporary art. I have constructed artificial categories under which to place various songs and albums, but many fit into (and may appear in) multiple categories. A few bands who heavily indulge in literary sources, like Rush and Styx, don’t quite make my own “heavy metal” category. Some bands that sit 101 Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 on the edge of rock/metal, like Scorpions and Buckcherry, do. Other examples, like Megadeth’s “Of Mice and Men,” Metallica’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” and Cradle of Filth’s “Nymphetamine” won’t feature at all, as the thematic inspiration is clear, but the textual connections tenuous.1 The categories constructed here are necessarily wide, but they allow for flexibility with the variety of approaches to literature and form. A segment devoted to the Bible as a source text has many pockets of variation not considered here (country music, Christian rock, Christian metal). -

Elena Is Not What I Body and Remove Toxins

VISIT HTTP://SPARTANDAILY.COM VIDEO SPORTS Hi: 68o A WEEKEND SPARTANS HOLD STROLL Lo: 43o ALONG THE ON TO CLOSE WIN OVER DONS GUADALUPE Tuesday RIVER PAGE 10 February 3, 2015 Volume 144 • Issue 4 Serving San Jose State University since 1934 LOCAL NEWS Electronic duo amps up Philz Coff ee Disney opens doors for SJSU design team BY VANESSA GONGORA @_princessness_ Disney continues to make dreams come true for future designers. Four students from San Jose State University were chosen by Walt Disney Imagineering as one of the top six college teams of its 24th Imaginations Design Competition. The top six fi nal teams were awarded a fi ve-day, all-expense-paid trip to Glendale, Calif., from Jan. 26–30, where they presented their projects to Imag- ineering executives and took part in an awards cere- mony on Jan. 30. According to the press release from Walt Disney Imagineering, the competition was created and spon- sored by Walt Disney Imagineering with the purpose of seeking out and nurturing the next generation of diverse Imagineers. This year’s Imaginations Design Competition consisted of students from American universities and Samson So | Spartan Daily colleges taking what Disney does best today and ap- Gavin Neves, one-half of the San Jose electronic duo “Hexes” performs “Witchhunt” at Philz plying it to transportation within a well-known city. Coffee’s weekly open mic night on Monday, Feb. 2. Open mic nights take place every Monday at The team’s Disney transportation creation needed the coffee shop from 6:30 p.m. to 9:15 p.m. -

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal *

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal * Stephen S. Hudson NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hudson.php KEYWORDS: Heavy Metal, Formenlehre, Form Perception, Embodied Cognition, Corpus Study, Musical Meaning, Genre ABSTRACT: This article presents a new framework for analyzing compound AABA form in heavy metal music, inspired by normative theories of form in the Formenlehre tradition. A corpus study shows that a particular riff-based version of compound AABA, with a specific style of buildup intro (Aas 2015) and other characteristic features, is normative in mainstream styles of the metal genre. Within this norm, individual artists have their own strategies (Meyer 1989) for manifesting compound AABA form. These strategies afford stylistic distinctions between bands, so that differences in form can be said to signify aesthetic posing or social positioning—a different kind of signification than the programmatic or semantic communication that has been the focus of most existing music theory research in areas like topic theory or musical semiotics. This article concludes with an exploration of how these different formal strategies embody different qualities of physical movement or feelings of motion, arguing that in making stylistic distinctions and identifying with a particular subgenre or style, we imagine that these distinct ways of moving correlate with (sub)genre rhetoric and the physical stances of imagined communities of fans (Anderson 1983, Hill 2016). Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory “Your favorite songs all sound the same — and that’s okay . -

Metaldata: Heavy Metal Scholarship in the Music Department and The

Dr. Sonia Archer-Capuzzo Dr. Guy Capuzzo . Growing respect in scholarly and music communities . Interdisciplinary . Music theory . Sociology . Music History . Ethnomusicology . Cultural studies . Religious studies . Psychology . “A term used since the early 1970s to designate a subgenre of hard rock music…. During the 1960s, British hard rock bands and the American guitarist Jimi Hendrix developed a more distorted guitar sound and heavier drums and bass that led to a separation of heavy metal from other blues-based rock. Albums by Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple in 1970 codified the new genre, which was marked by distorted guitar ‘power chords’, heavy riffs, wailing vocals and virtuosic solos by guitarists and drummers. During the 1970s performers such as AC/DC, Judas Priest, Kiss and Alice Cooper toured incessantly with elaborate stage shows, building a fan base for an internationally-successful style.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . “Heavy metal fans became known as ‘headbangers’ on account of the vigorous nodding motions that sometimes mark their appreciation of the music.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . Multiple sub-genres . What’s the difference between speed metal and death metal, and does anyone really care? (The answer is YES!) . Collection development . Are there standard things every library should have?? . Cataloging . The standard difficulties with cataloging popular music . Reference . Do people even know you have this stuff? . And what did this person just ask me? . Library of Congress added first heavy metal recording for preservation March 2016: Master of Puppets . Library of Congress: search for “heavy metal music” April 2017 . 176 print resources - 25 published 1980s, 25 published 1990s, 125+ published 2000s . -

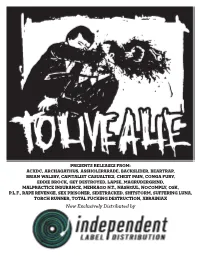

Now Exclusively Distributed by ACXDC Street Date: He Had It Coming, 7˝ AVAILABLE NOW!

PRESENTS RELEASES FROM: ACXDC, ARCHAGATHUS, ASSHOLEPARADE, BACKSLIDER, BEARTRAP, BRIAN WALSBY, CAPITALIST CASUALTIES, CHEST PAIN, CONGA FURY, EDDIE BROCK, GET DESTROYED, LAPSE, MAGRUDERGRIND, MALPRACTICE INSURANCE, MEHKAGO N.T., NASHGUL, NOCOMPLY, OSK, P.L.F., RAPE REVENGE, SEX PRISONER, SIDETRACKED, SHITSTORM, SUFFERING LUNA, TORCH RUNNER, TOTAL FUCKING DESTRUCTION, XBRAINIAX Now Exclusively Distributed by ACXDC Street Date: He Had It Coming, 7˝ AVAILABLE NOW! INFORMATION: Artist Hometown: Los Angeles, CA Key Markets: LA & CA, Texas, Arizona, DC, Baltimore MD, New York, Canada, Germany For Fans of: MAGRUDERGRIND, NASUM, NAPALM DEATH, DESPISE YOU ANTI-CHRIST DEMON CORE’s He Had it Coming repress features the original six song EP released in 2005 plus two tracks from the same session off the A Sign Of Impending Doom Compilation. The band formed in 2003, recorded these songs in 2005 and then vanished for awhile on a many- year hiatus, only to resurface and record and release a brilliant new EP and begin touring again in 2011/2012. The original EP is long sought after ARTIST: ACXDC by grindcore and powerviolence fiends around the country and this is your TITLE: He Had It Coming chance to grab the limited repress. LABEL: TO LIVE A LIE CAT#: TLAL64AB Marketing Points: FORMAT: 7˝ GENRE: Grindcore • Hugely Popular Band BOX LOT: NA • Repress of Long Sold Out EP SRLP: $5.48 • Huge Seller UPC: 616983334836 • Two Extra Songs In Additional To Originals EXPORT: NO RESTRICTIONS • Two Bonus Songs Never Before Pressed To Vinyl, In Additional To Originals Tracklist: 1. Dumb N Dumbshit 2. Death Spare Not The Tiger 3. Anti-Christ Demon Core 4. -

Thematic Patterns in Millennial Heavy Metal: a Lyrical Analysis

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 Thematic Patterns In Millennial Heavy Metal: A Lyrical Analysis Evan Chabot University of Central Florida Part of the Sociology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Chabot, Evan, "Thematic Patterns In Millennial Heavy Metal: A Lyrical Analysis" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2277. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2277 THEMATIC PATTERNS IN MILLENNIAL HEAVY METAL: A LYRICAL ANALYSIS by EVAN CHABOT B.A. University of Florida, 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 ABSTRACT Research on heavy metal music has traditionally been framed by deviant characterizations, effects on audiences, and the validity of criticism. More recently, studies have neglected content analysis due to perceived homogeneity in themes, despite evidence that the modern genre is distinct from its past. As lyrical patterns are strong markers of genre, this study attempts to characterize heavy metal in the 21st century by analyzing lyrics for specific themes and perspectives. Citing evidence that the “Millennial” generation confers significant developments to popular culture, the contemporary genre is termed “Millennial heavy metal” throughout, and the study is framed accordingly. -

Hipster Black Metal?

Hipster Black Metal? Deafheaven’s Sunbather and the Evolution of an (Un) popular Genre Paola Ferrero A couple of months ago a guy walks into a bar in Brooklyn and strikes up a conversation with the bartenders about heavy metal. The guy happens to mention that Deafheaven, an up-and-coming American black metal (BM) band, is going to perform at Saint Vitus, the local metal concert venue, in a couple of weeks. The bartenders immediately become confrontational, denying Deafheaven the BM ‘label of authenticity’: the band, according to them, plays ‘hipster metal’ and their singer, George Clarke, clearly sports a hipster hairstyle. Good thing they probably did not know who they were talking to: the ‘guy’ in our story is, in fact, Jonah Bayer, a contributor to Noisey, the music magazine of Vice, considered to be one of the bastions of hipster online culture. The product of that conversation, a piece entitled ‘Why are black metal fans such elitist assholes?’ was almost certainly intended as a humorous nod to the ongoing debate, generated mainly by music webzines and their readers, over Deafheaven’s inclusion in the BM canon. The article features a promo picture of the band, two young, clean- shaven guys, wearing indistinct clothing, with short haircuts and mild, neutral facial expressions, their faces made to look like they were ironically wearing black and white make up, the typical ‘corpse-paint’ of traditional, early BM. It certainly did not help that Bayer also included a picture of Inquisition, a historical BM band from Colombia formed in the early 1990s, and ridiculed their corpse-paint and black cloaks attire with the following caption: ‘Here’s what you’re defending, black metal purists. -

Gravetemple More Cohesive As a Unit, Allowing Them to Experiment with Their Sound Even Further

both in the recording studio and in a live Mammothfest takes place across various venues setting.” in Brighton from October 6th -8th, and tickets are BULLET POINTS www.Facebook.com/EntombedClandestine available now from their website. The long-running court case surrounding said: “Naturally, we are delighted with the www.Mammothfest.uk Brighton’s has announced the Entombed name has come to an end, decision of the courts. It’s a great relief Mammothfest its final lineup, with Akercocke, Vodun, Abhorrent Members of At The Gates, God Macabre, with the judge ruling against original vocalist that this issue is now finally ruled on and Decimation, Vigil, Confronted and more all Skitsystem and Tormented have come together Lars-Göran “LG” Petrov’s trademark of the we can return to focusing on giving people confirmed. They’ve also scored another UK exclusive to form Swedish death metal supergroup The name, and in favour of founding guitarist more Entombed. We have discussed ideas in the form of Belgian post-metallers Amenra, Lurking Fear, and will release their debut Alex Hellid, along with Nicke Andersson and plans of what we want to do and look who will headline Sunday night, joining exclusive album ‘Out Of The Voiceless Grave’ this August via and Uffe Cederlund. In a statement to forward to working together on creating Friday/Saturday headliners (respectively) Rotting Century Media. Blabbermouth, the three Entombed members the best possible Entombed for the future, Christ and Fleshgod Apocalypse. www.Facebook.com/TheLurkingFear ravetemple have just released ‘Impassable Fears’, their second album and follow up to 2007’s ‘The GHoly Down’. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE -

Vicious Ghoul Punks CRIMSON SPECTRE Team up with Eco-Violence Warriors UWHARRIA for a Battle of Epic Proportions

Vicious ghoul punks CRIMSON SPECTRE team up with Eco-violence warriors UWHARRIA for a battle of epic proportions. With a sound like the undead proletarian masses destroying their former masters in a blood-spattered zombie uprising, the unholy CRIMSON SPECTRE defy all that corporate punk and hardcore have become. Maybe because they’re old enough to remember a time before there was such a thing as “corporate punk and hardcore”, or maybe because they never sold-out to a formula sound or watered down lyrics. In the days when the US empire pretends to stand triumphant and declare that “there is no alternative”, fi ve (r)aging punk rockers never stopped believing in the power of rebel music or revolutionary dreams. Instead, CRIMSON SPECTRE will be the ones digging the graves, as they unearth monster riffs and bone-shattering beats to unleash on the oppressor class. CRIMSON SPECTRE is the evil smile on the face of the gravedigger. UWHARRIA started in 1999 as a group of environmental activists who were to create a musical extension of their activism. Eight days after forming, the band had written seven songs, played their fi rst show, and recorded a demo. These songs were based on the concept of nature glorifi cation: skunks, woodpeckers, sea turtles, dung beetles, and the human species being devoured by a jaguar. UWHARRIA blends early hardcore punk with NWOBHM and a heavy dose of crossover thrash, while being compared to BAD BRAINS, COC, RATOS DE PARAO, DRI, and oddly, CCR. The band’s favorite review was, “Sounds like Ronnie James Dio getting his