Summer 2018 Title Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Percy Savage Interviewed by Linda Sandino: Full Transcript of the Interview

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH FASHION Percy Savage Interviewed by Linda Sandino C1046/09 IMPORTANT Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 [0]20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. THE NATIONAL LIFE STORY COLLECTION INTERVIEW SUMMARY SHEET Ref. No.: C1046/09 Playback No.: F15198-99; F15388-90; F15531-35; F15591-92 Collection title: An Oral History of British Fashion Interviewee’s surname: Savage Title: Mr Interviewee’s forenames: Percy Sex: Occupation: Date of birth: 12.10.1926 Mother’s occupation: Father’s occupation: Date(s) of recording: 04.06.2004; 11.06.2004; 02.07.2004; 09.07.2004; 16.07.2004 Location of interview: Name of interviewer: Linda Sandino Type of recorder: Marantz Total no. of tapes: 12 Type of tape: C60 Mono or stereo: stereo Speed: Noise reduction: Original or copy: original Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Interview is open. Copyright of BL Interviewer’s comments: Percy Savage Page 1 C1046/09 Tape 1 Side A (part 1) Tape 1 Side A [part 1] .....to plug it in? No we don’t. Not unless something goes wrong. [inaudible] see well enough, because I can put the [inaudible] light on, if you like? Yes, no, lovely, lovely, thank you. -

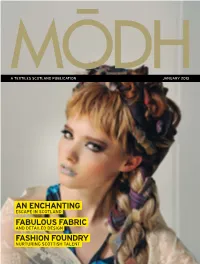

Modh-Textiles-Scotland-Issue-4.Pdf

A TEXTILES SCOTLAND PUBLICATION JANUARY 2013 AN ENCHANTING ESCAPE IN SCOTLAND FABULOUS FABRIC AND DETAILED DESIGN FASHION FOUNDRY NURTURING SCOTTISH TALENT contents Editor’s Note Setting the Scene 3 Welcome from Stewart Roxburgh 21 Make a statement in any room with inspired wallpaper Ten Must-Haves for this Season An Enchanting Escape 4 Some of the cutest products on offer this season 23 A fashionable stay in Scotland Fabulous Fabric Fashion Foundry 6 Uncovering the wealth of quality fabric in Scotland 32 Inspirational hub for a new generation Fashion with Passion Devil is in the Detail 12 Guest contributor Eric Musgrave shares his 38 Dedicated craftsmanship from start to fi nish thoughts on Scottish textiles Our World of Interiors Find us 18 Guest contributor Ronda Carman on why Scotland 44 Why not get in touch – you know you want to! has the interiors market fi rmly sewn up FRONT COVER Helena wears: Jacquard Woven Plaid with Herringbone 100% Merino Wool Fabric in Hair by Calzeat; Poppy Soft Cupsilk Bra by Iona Crawford and contributors Lucynda Lace in Ivory by MYB Textiles. Thanks to: Our fi rst ever guest contributors – Eric Musgrave and Ronda Carman. Read Eric’s thoughts on the Scottish textiles industry on page 12 and Ronda’s insights on Scottish interiors on page 18. And our main photoshoot team – photographer Anna Isola Crolla and assistant Solen; creative director/stylist Chris Hunt and assistant Emma Jackson; hair-stylist Gary Lees using tecni.art by L’Oreal Professionnel and the ‘O’ and irons by Cloud Nine, and make-up artist Ana Cruzalegui using WE ARE FAUX and Nars products. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Cloth, Fashion and Revolution 'Evocative' Garments and a Merchant's Know-How: Madame Teillard, Dressmaker at the Palais-Ro

CLOTH, FASHION AND REVOLUTION ‘EVOCATIVE’ GARMENTS AND A MERCHANT’S KNOW-HOW: MADAME TEILLARD, DRESSMAKER AT THE PALAIS-ROYAL By Professor Natacha Coquery, University of Lyon 2 (France) Revolutionary upheavals have substantial repercussions on the luxury goods sector. This is because the luxury goods market is ever-changing, highly competitive, and a source of considerable profits. Yet it is also fragile, given its close ties to fashion, to the imperative for novelty and the short-lived, and to objects or materials that act as social markers, intended for consumers from elite circles. However, this very fragility, related to fashion’s fleeting nature, can also be a strength. When we speak of fashion, we speak of inventiveness and constant innovation in materials, shapes, and colours. Thus, fashion merchants become experts in the fleeting and the novel. In his Dictionnaire universel de commerce [Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce], Savary des Bruslons assimilates ‘novelty’ and ‘fabrics’ with ‘fashion’: [Fashion] […] It is commonly said of new fabrics that delight with their colour, design or fabrication, [that they] are eagerly sought after at first, but soon give way in turn to other fabrics that have the charm of novelty.1 In the clothing trade, which best embodies fashion, talented merchants are those that successfully start new fashions and react most rapidly to new trends, which are sometimes triggered by political events. In 1763, the year in which the Treaty of Paris was signed to end the Seven Years’ War, the haberdasher Déton of Rue Saint-Honoré, Paris, ‘in whose shop one finds all fashionable merchandise, invented preliminary hats, decorated on the front in the French style, and on the back in the English manner.’2 The haberdasher made a clear and clever allusion to the preliminary treaty, signed a year earlier. -

September 2019 Cover Story Trajes De Charro

September 2019 Cover Story Trajes de Charro 멕시코 카우보이의 전통 의상 멕시코의 ‘차로’만큼 멋지게 차려입은 카우보이도 없을 것이다. 섬세한 자수 장식 재킷, 세선 세공의 벨트 버클, 정교한 문양이 들어간 모자 차림의 차로 덕분에 로데오 경기는 오페라 공연만큼이나 격식과 품위가 넘친다. Suit Up, Saddle Up You’ll never see a better-dressed cowboy than the Mexican charro. In exquisitely embroidered jackets, finely filigreed belt buckles and intricately embellished sombreros, they make going to the rodeo seem as refined as a trip to the opera. 1519년 스페인의 정복자 에르난 코르테스가 멕시코에 When Hernán Cortés arrived in Mexico in 1519, he 입성한 이래 스페인의 다양한 풍습과 화려한 의상도 이 땅에 brought centuries of Spanish customs and ornate styles of 전해졌다. 300여 년의 식민 통치 기간 스페인 문화는 멕시코 dress with him. Over the next 300 years, these would form 사회에 단단하게 뿌리를 내렸다. 특히 오늘날 멕시코 중서부 the bedrock of Mexican society, exemplified by the rise of 할리스코주의 과달라하라에 해당하는 지역을 중심으로 한 wealthy Spanish landowners who were the ultimate tier of 스페인 제국의 통치 지역 누에바갈리시아에서는 스페인 cattle ranchers and farmers known as chinacos. 출신의 기마병인 ‘치나코’가 목장과 농장을 소유하면서 Throughout the 19th century, the Spanish-derived 부유한 지배층으로 성장했다. chinaco slowly transformed into the uniquely Mexican 19세기에는 치나코에 영향을 받아 멕시코 고유의 카우보이 charro. While chinacos carried spears and wore flared ‘차로’가 탄생했다. 치나코가 창을 들고 다니며 무릎 높이에서 pants often left open up to the knee, charros carried ropes 양쪽으로 트이며 바지폭이 넓어지는 나팔바지를 입고 다녔다면, and wore straight-legged pants fitted above ankle boots. 차로는 밧줄을 들고 다니며 일자바지를 입고 바지 끝자락이 In 1920, a group of charros in Guadalajara founded 발목 높이의 부츠를 덮는 스타일을 고수했다. -

The Morgue File 2010

the morgue file 2010 DONE BY: ASSIL DIAB 1850 1900 1850 to 1900 was known as the Victorian Era. Early 1850 bodices had a Basque opening over a che- misette, the bodice continued to be very close fitting, the waist sharp and the shoulder less slanted, during the 1850s to 1866. During the 1850s the dresses were cut without a waist seam and during the 1860s the round waist was raised to some extent. The decade of the 1870s is one of the most intricate era of women’s fashion. The style of the early 1870s relied on the renewal of the polonaise, strained on the back, gath- ered and puffed up into an detailed arrangement at the rear, above a sustaining bustle, to somewhat broaden at the wrist. The underskirt, trimmed with pleated fragments, inserting ribbon bands. An abundance of puffs, borders, rib- bons, drapes, and an outlandish mixture of fabric and colors besieged the past proposal for minimalism and looseness. women’s daywear Victorian women received their first corset at the age of 3. A typical Victorian Silhouette consisted of a two piece dress with bodice & skirt, a high neckline, armholes cut under high arm, full sleeves, small waist (17 inch waist), full skirt with petticoats and crinoline, and a floor length skirt. 1894/1896 Walking Suit the essential “tailor suit” for the active and energetic Victorian woman, The jacket and bodice are one piece, but provide the look of two separate pieces. 1859 zouave jacket Zouave jacket is a collarless, waist length braid trimmed bolero style jacket with three quarter length sleeves. -

Weaving Twill Damask Fabric Using ‘Section- Scale- Stitch’ Harnessing

Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research Vol. 40, December 2015, pp. 356-362 Weaving twill damask fabric using ‘section- scale- stitch’ harnessing R G Panneerselvam 1, a, L Rathakrishnan2 & H L Vijayakumar3 1Department of Weaving, Indian Institute of Handloom Technology, Chowkaghat, Varanasi 221 002, India 2Rural Industries and Management, Gandhigram Rural Institute, Gandhigram 624 302, India 3Army Institute of Fashion and Design, Bangalore 560 016, India Received 6 June 2014; revised received and accepted 30 July 2014 The possibility of weaving figured twill damask using the combination of ‘sectional-scaled- stitched’ (SSS) harnessing systems has been explored. Setting of sectional, pressure harness systems used in jacquard have been studied. The arrangements of weave marks of twill damask using the warp face and weft face twills of 4 threads have been analyzed. The different characteristics of the weave have been identified. The methodology of setting the jacquard harness along with healds has been derived corresponding to the weave analysis. It involves in making the harness / ends in two sections; one section is to increase the figuring capacity by scaling the harness and combining it with other section of simple stitching harnessing of ends. Hence, the new harness methodology has been named as ‘section-scale-stitch’ harnessing. The advantages of new SSS harnessing to weave figured twill damask have been recorded. It is observed that the new harnessing methodology has got the advantages like increased figuring capacity with the given jacquard, less strain on the ends and versatility to produce all range of products of twill damask. It is also found that the new harnessing is suitable to weave figured double cloth using interchanging double equal plain cloth, extra warp and extra weft weaving. -

Of Gucci, Crasi Vira- Le, Collisione Digitale Tra Il Social Del Momento Clubhouse Marchio, Questo Nome, Questa Saga

il primo quotidiano della moda e del lusso Anno XXXII n. 074 Direttore ed editore Direttore MFvenerdì fashion 16 aprile 2021 MF fashion Paolo Panerai - Stefano RoncatoI 16.04.21 CClub-Houselub-House UN LOOK DELLA COLLEZIONE ARIA DI GUCCI ooff GGucciucci DDalal SSavoyavoy a uunn EEdenden lluminosouminoso ddoveove ssii pprenderende iill vvolo.olo. IIll vvideoideo cco-direttoo-diretto ddaa AAlessandrolessandro MMicheleichele e ddaa FFlorialoria SSigismondiigismondi ssperimentaperimenta ppensandoensando aaii 110000 aanninni ddellaella mmaisonaison ddellaella ddoppiaoppia GG,, ssvelandovelando ll’inedito’inedito ddialogoialogo cconon DDemnaemna GGvasaliavasalia ddii BBalenciagaalenciaga o rrilettureiletture ddelel llavoroavoro ddii TTomom FFord.ord. TTrara lluccicanzeuccicanze ddii ccristalli,ristalli, ssartorialeartoriale ssensuale,ensuale, eelementilementi eequestriquestri ffetishetish e rrimandiimandi a HHollywoodollywood ucci gang, Lil Pump canta. Un innocente tailleur si avvicina al- la cam e svela the body of evidence. Glitter, cristalli, ricami, La scritta Balenciaga sulla giacca, le calze con il logo GG. Quei Gdue nomi uniti, che tanto hanno scatenato l’interesse di que- sti giorni alla fine sono comparsi (vedere MFF del 12 aprile). Gucci e Balenciaga, sovrapposti nei ricami e nelle fantasie, in una composizione che farà impazzire i consumatori. Kering ringrazia. Ma ringrazia anche per la collezione Aria che incomincia a svelare i festeggiamenti per i 100 anni della maison Gucci. Un mondo che è andato in scena in quel corto- metraggio co-diretto da Alessandro Michele e da Floria Sigismondi, la regista avantguard e visionaria dei videoclip musicali che aveva già col- laborato con la fashion house della doppia G. E in effetti la musica ha un grande peso, oltre al ritmo diventa una colonna sonora con canzoni che citano la parola Gucci a più riprese, super virale. -

Charles James, Um Astro Sem Atmosfera No Mundo Da Moda

[por que ler...?] [ MARIA LUCIA BUENO ] Professora do Instituto de Artes e Design da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (MG). Doutora em Sociologia (IFCH-UNICAMP), com pós-doutorado em Sociologia da Arte, da Cultura e da Moda (EHESS e Université Paris-Est ). É autora, entre outros, de Artes plásticas no século XX: modernidade e globalização (Imprensa Oficial, 2001) e organizadora de Sociologia das artes visuais no Brasil (Senac, 2012). E-mail: [email protected] Charles James, um astro sem atmosfera no mundo da moda [ 39 ] Charles James fotografado em 1952 por Michael Vaccaro. Foto reproduzida na catálogo (p. 52). [ por que ler...? | MARIA LUCIA BUENO ] Estilistas como Christian Dior e Chanel, ícones na cultura de moda do século XX, tiveram seus nomes ligados a marcas prestígio que permanecem ativas. Na história da moda, as referências mais longevas e legitimadas geralmente estão associadas a uma grife ou a um perfume, os principais artífices da construção da memória do trabalho dos profissionais do setor. A importância histórica tornou-se proporcional ao peso econômico e simbólico das marcas, pois são elas que financiam as publicações, as grandes exposições, a manutenção do acervo material, as pesquisas, os filmes, os documentários, uma vez que é na perenidade da influência do costureiro que reside a sua força simbólica. Charles James (Surrey, Reino Unido,1906 – Nova York, Estados Unidos, 1978), um dos mais inventivos costureiros do período da alta-costura, o único que atuou a partir dos Estados Unidos, foi referência incontestável no mundo da moda do anos 1940 e 1950. Mas, em razão do seu fracasso comercial e por não ter seu nome associado a uma marca ou a um perfume, ficou quase esquecido, mantendo-se como uma lem- brança vaga entre pesquisadores e profissionais da área – mesmo assim, a partir de referências muito restritas, como os vestidos de baile fotografados por Cecil Beaton. -

Fashion Trends 2016

Fashion Trends 2016 U.S. & U.K. Report [email protected] Intro With every query typed into a search bar, we are given a glimpse into user considerations or intentions. By compiling top searches, we are able to render a strong representation of the population and gain insight into this population’s behavior. In our second iteration of the Google Fashion Trends Report, we are excited to introduce data from multiple markets. This report focuses on apparel trends from the United States and United Kingdom to enable a better understanding of how trends spread and behaviors emerge across the two markets. We are proud to share this iteration and look forward to hearing back from you. Olivier Zimmer | Trends Data Scientist Yarden Horwitz | Trends Brand Strategist Methodology To compile a list of accurate trends within the fashion industry, we pulled top volume queries related to the apparel category and looked at their monthly volume from May 2014 to May 2016. We first removed any seasonal effect, and then measured the year-over-year growth, velocity, and acceleration for each search query. Based on these metrics, we were able to classify the queries into similar trend patterns. We then curated the most significant trends to illustrate interesting shifts in behavior. Query Deseasonalized Trend 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 Query 2016 Characteristics Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Top Risers a Spotlight on an Extensive List and Decliners Top Trending of the Top Volume Themes Fashion Trends Trend Categories To identify top trends, we categorized past data into six different clusters based on Sustained Seasonal Rising similar behaviors. -

ALL the PRETTY HORSES.Hwp

ALL THE PRETTY HORSES Cormac McCarthy Volume One The Border Trilogy Vintage International• Vintage Books A Division of Random House, Inc. • New York I THE CANDLEFLAME and the image of the candleflame caught in the pierglass twisted and righted when he entered the hall and again when he shut the door. He took off his hat and came slowly forward. The floorboards creaked under his boots. In his black suit he stood in the dark glass where the lilies leaned so palely from their waisted cutglass vase. Along the cold hallway behind him hung the portraits of forebears only dimly known to him all framed in glass and dimly lit above the narrow wainscotting. He looked down at the guttered candlestub. He pressed his thumbprint in the warm wax pooled on the oak veneer. Lastly he looked at the face so caved and drawn among the folds of funeral cloth, the yellowed moustache, the eyelids paper thin. That was not sleeping. That was not sleeping. It was dark outside and cold and no wind. In the distance a calf bawled. He stood with his hat in his hand. You never combed your hair that way in your life, he said. Inside the house there was no sound save the ticking of the mantel clock in the front room. He went out and shut the door. Dark and cold and no wind and a thin gray reef beginning along the eastern rim of the world. He walked out on the prairie and stood holding his hat like some supplicant to the darkness over them all and he stood there for a long time. -

Autumn 2017 Cover

Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 Front cover image: John June, 1749, print, 188 x 137mm, British Museum, London, England, 1850,1109.36. The Journal of Dress History Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 Managing Editor Jennifer Daley Editor Alison Fairhurst Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org i The Journal of Dress History Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2017 ISSN 2515–0995 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2017 The Association of Dress Historians Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession number: 988749854 The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer–reviewed environment. The journal is published biannually, every spring and autumn. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is distributed completely free of charge, solely for academic purposes, and not for sale or profit. The Journal of Dress History is published on an Open Access platform distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The editors of the journal encourage the cultivation of ideas for proposals.