[J-81-2020] in the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania Western District Baer, C.J., Saylor, Todd, Donohue, Dougherty, Wecht, Mundy, Jj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 6, 2021 To: General Authorities; General O Cers

May 6, 2021 To: General Authorities; General Owcers; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, and Temple Presidencies; Bishoprics and Branch Presidencies Senior Service Missionaries Around the World Dear Brothers and Sisters: We are deeply grateful for the faithful service of senior missionaries around the world and for the signiucant contributions they make in building the kingdom of God. We continue to encourage members to serve either full- time missions away from home as their circumstances permit or senior service missions if they are unable to leave home. Starting this May, and based on Area Presidency direction and approval, eligible members anywhere in the world may be considered for a senior service mission. Under the direction of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, each senior service missionary will receive a call from his or her stake, mission, or district president. Senior service missionaries (individuals and couples) assist Church functions and operations in a variety of ways. Additional details are included in the enclosed document. Information for members interested in serving as a senior service missionary can be found at seniormissionary.ChurchofJesusChrist.org. Sincerely yours, {e First Presidency Senior Service Missionary Opportunities May 6, 2021 Opportunities to serve as senior service missionaries are presented to members through a website (seniormissionary.ChurchofJesusChrist.org) that allows a customized search to match Church needs to talents, interests, and availability of members. Once an opportunity is identiued, senior service missionaries are called, under the direction of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, through their stake, mission or district president. -

The Joseph Smith Memorial Monument and Royalton's

The Joseph Smith Memorial Monument and Royalton’s “Mormon Affair”: Religion, Community, Memory, and Politics in Progressive Vermont In a state with a history of ambivalence toward outsiders, the story of the Mormon monument’s mediation in the local rivalry between Royalton and South Royalton is ultimately a story about transformation, religion, community, memory, and politics. Along the way— and in this case entangled with the Mormon monument—a generation reshaped town affairs. By Keith A. Erekson n December 23, 1905, over fifty members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) gathered to Odedicate a monument to their church’s founder, Joseph Smith, near the site of his birth on a hill in the White River Valley. Dur- ing the previous six months, the monument’s designer and project man- agers had marshaled the vast resources of Vermont’s granite industry to quarry and polish half a dozen granite blocks and transport them by rail and horse power; they surmounted all odds by shoring up sagging ..................... KEITH A. EREKSON is a Ph.D. candidate in history at Indiana University and is the assistant editor of the Indiana Magazine of History. Vermont History 73 (Summer/Fall 2005): 117–151. © 2005 by the Vermont Historical Society. ISSN: 0042-4161; on-line ISSN: 1544-3043 118 ..................... Joseph Smith Memorial Monument (Lovejoy, History, facing 648). bridges, crossing frozen mud holes, and beating winter storms to erect a fifty-foot, one-hundred-ton monument considered to be the largest of its kind in the world. Since 1905, Vermont histories and travel litera- ture, when they have acknowledged the monument’s presence, have generally referred to it as a remarkable engineering feat representative of the state’s prized granite industry.1 What these accounts have omitted is any indication of the monument’s impact upon the local community in which it was erected. -

Callings in the Church

19. Callings in the Church This chapter provides information about calling presented for a sustaining vote. A person who is and releasing members to serve in the Church. The being considered for a calling is not notified until Chart of Callings, 19.7, lists selected callings and the calling is issued. specifies who recommends a person, who approves When a calling will be extended by or under the the recommendation, who sustains the person, and direction of the stake president, the bishop should who calls and sets apart the person. Callings on the be consulted to determine the member’s worthiness chart are filled according to need and as members and the family, employment, and Church service cir- are available. cumstances. The stake presidency then asks the high council to sustain the decision to call the person, if 19.1 necessary according to the Chart of Callings. Determining Whom to Call When a young man or young woman will be called to a Church position, a member of the bishopric ob- 19.1.1 tains approval from the parents or guardians before General Guidelines issuing the calling. A person must be called of God to serve in the Leaders may extend a Church calling only after Church (see Articles of Faith 1:5). Leaders seek the (1) a person’s membership record is on file in the guidance of the Spirit in determining whom to call. ward and has been carefully reviewed by the bishop They consider the worthiness that may be required or (2) the bishop has contacted the member’s previ- for the calling. -

The Folklore of Mormon Missionaries

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Faculty Honor Lectures Lectures 4-12-1981 On Being Human: The Folklore of Mormon Missionaries William A. Wilson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honor_lectures Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, William A., "On Being Human: The Folklore of Mormon Missionaries" (1981). Faculty Honor Lectures. Paper 60. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honor_lectures/60 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Honor Lectures by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. On Being Human: The Folklore of Mormon Missionaries by William A. Wilson 64th Faculty Honor Lecture Utah State University Logan, Utah SIXTY. FOURTH HONOR LECTURE DELIVERED AT THE UNIVERSITY A basic objective of the Faculty Association of Utah State Uni- versity, in the words of its constitution, is: to encourage intellectual growth and development of its members by sponsoring and arranging for the publication of two annual faculty research lectures in the fields of (1) the biological and exact sciences, including engineering, called the Annual Faculty Honor Lecture in the Natural Sciences; and (2) the humanities and social sciences, including education and business administra tion, called the Annual Faculty Honor Lecture in the Humanities. The administration of the University is sympathetic with these aims and shares, through the Scholarly Publications Committee, the costs of publishing and distributing these lectures. Lecturers are chosen by a standing committee of the Faculty Association. -

Who Is a Member of the District Assembly? Who Is a Member of the District Conventions? (A Compiled and Edited Document, Prepared by Brian E

Who Is a Member of the District Assembly? Who Is a Member of the District Conventions? (A compiled and edited document, prepared by Brian E. Wilson, Updated March 3, 2018) District Assembly Manual 201: Membership of the District Assembly The district assembly shall be composed of the following ex officio (by virtue of office) members: 1. All assigned elders 2. All assigned deacons 3. All assigned district-licensed ministers 4. The district secretary 5. The district treasurer 6. Chairpersons of standing district committees reporting to the District Assembly 7. Any lay presidents of Nazarene institutions of higher education, whose local church membership is on the district. 8. The District SDMI chairperson (Sunday School and Discipleship International) 9. District age-group ministries international directors (children and adult) 10. The District SDMI Board 11. The president of the District NYI (Nazarene Youth International) 12. The president of the District NMI (Nazarene Missions International) 13. The newly elected superintendent or vice superintendent of each local SDMI Board 14. The newly elected president or vice president of each local NYI 15. The newly elected president or vice president of each local NMI 16. (OR) an elected alternate may represent the local NMI, NYI, and SDMI organizations in the district assembly 17. The lay members of the District Advisory Board 18. Active lay missionaries whose local church membership is on the district 19. All retired lay missionaries whose local church membership is on the district who were active missionaries at the time of retirement In addition to the ex officio delegates, each local church and church-type mission in the assembly district may send locally-elected lay delegates as members of the District Assembly. -

NDS Endorsement Part 3

Part 3: Instructions for Student Commitment and Confidential Report Instructions to all Applicants: Applicants to the CES schools commit to live the ideals and principles of the gospel of Jesus Christ and to maintain the standards of conduct as taught by The Church of Jesus Christ of latter-day Saints. By accepting admission to these schools, individuals reconfirm their commitment to observe these standards. After reading this page, you must Interview With your LDS bishop or branch president. LDS applicants must also interview with a member of their current stake or district presidency. Non-LDS applicants may interview with any local LDS Bishop, then will be contacted by the university chaplain for a second interview after CES receives Part 3. Your ecclesiastical leader w1ll complete his section of Part 3 and send the entire section directly to Educational Outreach. Please sign Part 3 at the conclusion of your interview. Instructions to the Interviewing Officer: Please review in detail the Honor Code and the Dress and Grooming Standards with the applicant. The First Presidency directs ecclesiastical leaders to not endorse students with unresolved worthiness or activity problems. A student who is admitted but is not actually worthy of the ecclesiastical endorsement given is not fully prepared spiritually and displaces another student who is qualified to attend. Individuals who are 1) less active, 2) unworthy, or 3) under Church discipline should not be endorsed for admission until these issues have been completely resolved and the requisite standards of worthiness are met. If endorsed, please forward this form directly to the stake or district president. -

A Historical Examination of the Views of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and the Reorganized Church of Jesus

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1968 A Historical Examination of the Views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints on Four Distinctive Aspects of the Doctrine of Deity Taught by the Prophet Joseph Smith Joseph F. McConkie Sr. Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation McConkie, Joseph F. Sr., "A Historical Examination of the Views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter- Day Saints and the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints on Four Distinctive Aspects of the Doctrine of Deity Taught by the Prophet Joseph Smith" (1968). Theses and Dissertations. 4925. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4925 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. i A historical examination OF THE VIEWS OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTERDAYLATTER DAY SAINTS AND THE reorganized CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTERDAYLATTER DAY SAINTS ON FOUR distinctive ASPECTS OPOFTHE DOCTRINE OF DEITY TAUGHT BY THE PROPHET JOSEPH SMITH A thesis presented to the graduate studies in religious instruction brigham young -

The First 12 Weeks

In-Field Training for New Missionaries The First 12 Weeks For New Missionaries and Trainers Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah © 2013 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the USA. English approval: 8/13. 12177 000 In-FieldIn-Field TrainingTraining forfor NewNew MissionariesMissionaries Introduction To the New Missionary our experience in the missionary training center build on the foundation established at the MTC by (MTC) was designed to help you learn your understanding and living all of the principles of mis- Ypurpose as a missionary and how to prepare sionary work found in Preach My Gospel. Strive to and teach investigators by the Spirit, according to become the kind of missionary who could, if called their interests and needs. upon, train a new missionary by the end of your first 12 weeks in the mission field. Your purpose for the rest of your mission is to follow the promptings of the Spirit as you invite an in- To accomplish this objective, follow these principles: creasing number of people “to come unto Christ by n Be obedient to mission rules and the direction helping them receive the restored gospel through contained in the Missionary Handbook. faith in Jesus Christ and His Atonement, repentance, baptism, receiving the gift of the Holy Ghost, and n Love, serve, and listen to your companion. enduring to the end” (Preach My Gospel [2004], 1). n Eagerly participate as a fully contributing member To accomplish this purpose, you will continue to of your companionship. 1 Introduction The Lord has blessed you with unique gifts and the first 12 weeks of training. -

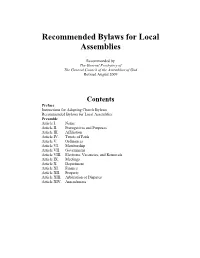

Recommended Bylaws for Local Assemblies

Recommended Bylaws for Local Assemblies Recommended by The General Presbytery of The General Council of the Assemblies of God Revised August 2009 Contents Preface Instructions for Adopting Church Bylaws Recommended Bylaws for Local Assemblies Preamble Article I. Name Article II. Prerogatives and Purposes Article III. Affiliation Article IV. Tenets of Faith Article V. Ordinances Article VI. Membership Article VII. Government Article VIII. Elections, Vacancies, and Removals Article IX. Meetings Article X. Department Article XI. Finance Article XII. Property Article XIII. Arbitration of Disputes Article XIV. Amendments Preface In response to an increasing demand for some practical rules of order to serve as a guide in the development and conducting of affairs of local assemblies, the General Council Presbytery of The General Council of the Assemblies of God has prepared this document titled "Recommended Bylaws for Local Assemblies." These provisions have been thought out carefully and should have full and careful consideration before adoption. It is desirable that the form of organization for the church be kept as simple as possible. Boards should not be multiplied just to give offices to people. It may not be desirable to elect any deacons for longer than 1 year. There is, however, a legal reason for the election of trustees for 3 years each: so that some trustees are always carried over each year and at no time do all trustees go out of office together. Their terms should, therefore, be staggered. It would be well to impress upon the members of the church board at the time of their election that they have been chosen by the assembly to serve, rather than to rule. -

Robert S. Treff V. GORDON B. HINCKLEY, President of The

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Utah Supreme Court Briefs 2000 Robert S. Treff .v GORDON B. HINCKLEY, President of The hC urch of Jesus Christ of Latter- day Saints, THOMAS S. MONSON, First Counselor in the First Presidency of The hC urch of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, JAMES E. FAUST, Second Counselor in the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, DORIS WILSON, The Division of Family Services for the State of Utah, SUSAN CHANDLER, WENDY WFolloRIGHTw this and addit,ion JAMESal works at: h ttBAps://dUigitMalcommonGARDNERs.law.byu.edu/byu_s, Sc2HEILA DPOart YLof theE,Law J Cohnommon sand Jane Does #1-30, all defendants sOruediginal B indirief Submittvidualed to thely U tahin S uppreemerson Courtal; di gaitindzed b yoffic the Howialard Wc.a Hpunatecr Litawies : Library, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; machine-generated OBCrRief, ma yof con tAainpp errorels. lee Robert S. Treff; pro se. Utah Supreme Court Randy T. Austin, Amy S. Thomas; Kirton & McConkie; attorneys for appellees. Recommended Citation Brief of Appellee, Treff .v Hinckley, No. 20000777.00 (Utah Supreme Court, 2000). https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/byu_sc2/577 This Brief of Appellee is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Supreme Court Briefs by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. Policies regarding these Utah briefs are available at http://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/utah_court_briefs/policies.html. Please contact the Repository Manager at [email protected] with questions or feedback. -

District Highlights March 2019 Vol

Western PA District Highlights March 2019 Vol. 19 No. 2 Jesus said, “Come, follow me!” The Season of Lent begins this year on March 6th. March 6th is my birthday and this year it also happens to be Ash Wednesday. How does a person celebrate his birth and at the same time ponder his mortality? Well, that is my problem not yours! But getting back to Lent - Lent is that 40 day period before Easter in which we are challenged to deepen our personal discipleship under the Lordship of Christ. We take it upon ourselves to ask again what it means to follow Jesus. How do we know if we are following Jesus? What are the telltale signs? We could respond with the “go to” answers like “going to church, giving to the church, reading the Bible, praying to the Lord day by day.” But is there more to following Jesus than those things? Again, how do we know if we are following Jesus? What are the telltale signs? We could perhaps list many things. But I want to suggest to you that a telltale sign that a person is following Jesus is this: When faced with a choice between Jesus and the world, he chooses Jesus. When faced with a choice between Jesus’ attitude and the world’s arrogance, he chooses Jesus. When faced with a choice between Jesus’ abounding love for others and the world’s meanness, he chooses Jesus. It may be simplistic or even redundant to put it this way, but the telltale sign that a person is following Jesus is that he chooses Jesus in everything. -

History of the South African Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, 1853-1970

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1971 History of the South African Mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, 1853-1970 Farrell Ray Monson Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Mormon Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Monson, Farrell Ray, "History of the South African Mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, 1853-1970" (1971). Theses and Dissertations. 4951. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4951 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. HISTORY OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN MISSION OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRITCHRIST OF LATTERDAYLATTER DAY SAINTS 185319701853 1970 A thesis presented to the department of church history and doctrine brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts by farrell ray monson may 1971 copyright 1971 by farrellfarparre 11 ray monson roy utah acknowledgments this history of the south african mission 185319701853 1970 was not completed without the invaluable assistance of many friends teachers librarians and families failure to acknowledge them all does not mean that the writer is