The Folklore of Mormon Missionaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mormon Trail

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Mormon Trail William E. Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hill, W. E. (1996). The Mormon Trail: Yesterday and today. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MORMON TRAIL Yesterday and Today Number: 223 Orig: 26.5 x 38.5 Crop: 26.5 x 36 Scale: 100% Final: 26.5 x 36 BRIGHAM YOUNG—From Piercy’s Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley Brigham Young was one of the early converts to helped to organize the exodus from Nauvoo in Mormonism who joined in 1832. He moved to 1846, led the first Mormon pioneers from Win- Kirtland, was a member of Zion’s Camp in ter Quarters to Salt Lake in 1847, and again led 1834, and became a member of the first Quo- the 1848 migration. He was sustained as the sec- rum of Twelve Apostles in 1835. He served as a ond president of the Mormon Church in 1847, missionary to England. After the death of became the territorial governor of Utah in 1850, Joseph Smith in 1844, he was the senior apostle and continued to lead the Mormon Church and became leader of the Mormon Church. -

May 6, 2021 To: General Authorities; General O Cers

May 6, 2021 To: General Authorities; General Owcers; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, and Temple Presidencies; Bishoprics and Branch Presidencies Senior Service Missionaries Around the World Dear Brothers and Sisters: We are deeply grateful for the faithful service of senior missionaries around the world and for the signiucant contributions they make in building the kingdom of God. We continue to encourage members to serve either full- time missions away from home as their circumstances permit or senior service missions if they are unable to leave home. Starting this May, and based on Area Presidency direction and approval, eligible members anywhere in the world may be considered for a senior service mission. Under the direction of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, each senior service missionary will receive a call from his or her stake, mission, or district president. Senior service missionaries (individuals and couples) assist Church functions and operations in a variety of ways. Additional details are included in the enclosed document. Information for members interested in serving as a senior service missionary can be found at seniormissionary.ChurchofJesusChrist.org. Sincerely yours, {e First Presidency Senior Service Missionary Opportunities May 6, 2021 Opportunities to serve as senior service missionaries are presented to members through a website (seniormissionary.ChurchofJesusChrist.org) that allows a customized search to match Church needs to talents, interests, and availability of members. Once an opportunity is identiued, senior service missionaries are called, under the direction of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, through their stake, mission or district president. -

![[J-81-2020] in the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania Western District Baer, C.J., Saylor, Todd, Donohue, Dougherty, Wecht, Mundy, Jj](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9865/j-81-2020-in-the-supreme-court-of-pennsylvania-western-district-baer-c-j-saylor-todd-donohue-dougherty-wecht-mundy-jj-709865.webp)

[J-81-2020] in the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania Western District Baer, C.J., Saylor, Todd, Donohue, Dougherty, Wecht, Mundy, Jj

[J-81-2020] IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PENNSYLVANIA WESTERN DISTRICT BAER, C.J., SAYLOR, TODD, DONOHUE, DOUGHERTY, WECHT, MUNDY, JJ. RENEE' A. RICE : No. 3 WAP 2020 : : Appeal from the Order of the v. : Superior Court entered June 11, : 2019 at No. 97 WDA 2018, : reversing the Order of the Court of DIOCESE OF ALTOONA-JOHNSTOWN, : Common Pleas of Blair County BISHOP JOSEPH ADAMEC (RETIRED), : entered December 15, 2017 at No. MONSIGNOR MICHAEL E. SERVINSKY, : 2016 GN 1919, and remanding. EXECUTOR OF THE ESTATE OF BISHOP : JAMES HOGAN, DECEASED, AND : ARGUED: October 20, 2020 REVEREND CHARLES F. BODZIAK : : : APPEAL OF: DIOCESE OF ALTOONA- : JOHNSTOWN, BISHOP JOSEPH ADAMEC : (RETIRED), MONSIGNOR MICHAEL E. : SERVINSKY, EXECUTOR OF THE : ESTATE OF BISHOP JAMES HOGAN, : DECEASED : OPINION JUSTICE DONOHUE DECIDED: JULY 21, 2021 In this appeal, we address the proper application of the statute of limitations to a tort action filed by Renee’ Rice (“Rice”) against the Diocese of Altoona-Johnstown and its bishops (collectively, the “Diocese”) for their alleged role in covering up and facilitating a series of alleged sexual assaults committed by the Reverend Charles F. Bodziak. Rice alleged that Bodziak sexually abused her from approximately 1974 through 1981. She did not file suit against Bodziak or the Diocese until June 2016, thirty-five years after the alleged abuse stopped. For the reasons set forth herein, we conclude that a straightforward application of Pennsylvania’s statute of limitations requires that Rice’s complaint be dismissed as untimely. Accordingly, we reverse the order of the Superior Court and reinstate the trial court’s dismissal of the case. -

The Joseph Smith Memorial Monument and Royalton's

The Joseph Smith Memorial Monument and Royalton’s “Mormon Affair”: Religion, Community, Memory, and Politics in Progressive Vermont In a state with a history of ambivalence toward outsiders, the story of the Mormon monument’s mediation in the local rivalry between Royalton and South Royalton is ultimately a story about transformation, religion, community, memory, and politics. Along the way— and in this case entangled with the Mormon monument—a generation reshaped town affairs. By Keith A. Erekson n December 23, 1905, over fifty members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) gathered to Odedicate a monument to their church’s founder, Joseph Smith, near the site of his birth on a hill in the White River Valley. Dur- ing the previous six months, the monument’s designer and project man- agers had marshaled the vast resources of Vermont’s granite industry to quarry and polish half a dozen granite blocks and transport them by rail and horse power; they surmounted all odds by shoring up sagging ..................... KEITH A. EREKSON is a Ph.D. candidate in history at Indiana University and is the assistant editor of the Indiana Magazine of History. Vermont History 73 (Summer/Fall 2005): 117–151. © 2005 by the Vermont Historical Society. ISSN: 0042-4161; on-line ISSN: 1544-3043 118 ..................... Joseph Smith Memorial Monument (Lovejoy, History, facing 648). bridges, crossing frozen mud holes, and beating winter storms to erect a fifty-foot, one-hundred-ton monument considered to be the largest of its kind in the world. Since 1905, Vermont histories and travel litera- ture, when they have acknowledged the monument’s presence, have generally referred to it as a remarkable engineering feat representative of the state’s prized granite industry.1 What these accounts have omitted is any indication of the monument’s impact upon the local community in which it was erected. -

FD Supp 04 Bednar the Spirit and Purposes of Gathering Oct 31 2006

The Spirit and Purposes of Gathering Elder David A. Bednar Brigham Young University–Idaho Devotional October 31, 2006 Sister Bednar and I are grateful to be back on campus with you this afternoon. We love you. My general authority colleagues who are assigned to speak at BYU–Idaho devotionals often ask me if I have any advice for them as they prepare their messages. My answer is always the same. Do not underestimate the students at Brigham Young University– Idaho. Those young people will come to the devotional eager to worship and to learn the basic doctrines of the restored gospel. Those young men and women will come to the devotional with their scriptures in hand and ready to use them. They will come to the devotional prepared to seek learning by study and also by faith. Treat and teach those young men and women as who they really are. This afternoon I will take my own advice. During the time Sister Bednar and I served here in Rexburg, I often said from this pulpit that the greatest compliment I could give you as students is to treat you and to teach you as who you are spirit sons and daughters of our Heavenly Father with a particular and important purpose to fulfill in these latter days. I now plead and pray for the Holy Ghost to assist me and you as together we discuss the spirit and purposes of gathering. We are met together today to participate in the groundbreaking for two buildings on this campus—the addition to the Manwaring Center and the new auditorium. -

Pres. Russell M. Nelson Elder David A. Bednar Elder Scott D. Whiting President of the Church Quorum of the Twelve Apostles General Authority Seventy

SAT SATURDAY MORNING SESSION 190TH SEMIANNUAL GENERAL CONFERENCE Pres. Russell M. Nelson Elder David A. Bednar Elder Scott D. Whiting President of the Church Quorum of the Twelve Apostles General Authority Seventy The world has been overturned Tests in “the school of mortality” are Latter-day Saints are commanded by in recent months by a global a vital element in eternal progression. the Savior to become “even as [He is].” pandemic, raging wildfires and Scriptural words such as “prove,” “ex- “Consider asking a trusted family mem- other natural disasters. amine” and “try” are used to describe ber, spouse, friend, or spiritual leader “I grieve with each of you who knowledge about, understanding of what attribute of Jesus Christ we are in has lost a loved one during this and devotion to the plan of happiness need of.” It is vital to also ask Heavenly time. And I pray for all who are and the Savior’s Atonement. Father where to focus efforts. “He has a currently suffering.” “The year 2020 has been marked, perfect view of us and will lovingly show Yet the work of the Lord moves in part, by a global pandemic that has us our weakness.” steadily forward. “Amid social proved, examined and tried us in many President Russell M. Nelson taught: distancing, face masks and Zoom meetings, we have ways. I pray that we as individuals and families are learning the “When we choose to repent, we choose to change!” learned to do some things differently, and some even more valuable lessons that only challenging experiences can teach us.” After committing to change and repent, the next step is to choose effectively. -

Callings in the Church

19. Callings in the Church This chapter provides information about calling presented for a sustaining vote. A person who is and releasing members to serve in the Church. The being considered for a calling is not notified until Chart of Callings, 19.7, lists selected callings and the calling is issued. specifies who recommends a person, who approves When a calling will be extended by or under the the recommendation, who sustains the person, and direction of the stake president, the bishop should who calls and sets apart the person. Callings on the be consulted to determine the member’s worthiness chart are filled according to need and as members and the family, employment, and Church service cir- are available. cumstances. The stake presidency then asks the high council to sustain the decision to call the person, if 19.1 necessary according to the Chart of Callings. Determining Whom to Call When a young man or young woman will be called to a Church position, a member of the bishopric ob- 19.1.1 tains approval from the parents or guardians before General Guidelines issuing the calling. A person must be called of God to serve in the Leaders may extend a Church calling only after Church (see Articles of Faith 1:5). Leaders seek the (1) a person’s membership record is on file in the guidance of the Spirit in determining whom to call. ward and has been carefully reviewed by the bishop They consider the worthiness that may be required or (2) the bishop has contacted the member’s previ- for the calling. -

"Lamanites" and the Spirit of the Lord

"Lamanites" and the Spirit of the Lord Eugene England EDITORS' NOTE: This issue of DIALOGUE, which was funded by Dora Hartvigsen England and Eugene England Sr., and their children and guest-edited by David J. Whittaker, has been planned as an effort to increase understanding of the history of Mor- mon responses to the "Lamanites" — native peoples of the Americas and Poly- nesia. We have invited Eugene England, Jr., professor of English at BYU, to document his parents' efforts, over a period of forty years, to respond to what he names "the spirit of Lehi" — a focused interest in and effort to help those who are called Lamanites. His essay also reviews the sources and proper present use of that term (too often used with misunderstanding and offense) and the origins and prophesied future of those to whom it has been applied. y parents grew up conditioned toward racial prejudice — as did most Americans, including Mormons, through their generation and into part of mine. But something touched my father in his early life and grew con- stantly in him until he and my mother were moved at mid-life gradually to consecrate most of their life's earnings from then on to help Lamanites. I wish to call what touched them "the spirit of Lehi." It came in its earliest, somewhat vague, form to my father when he left home as a seventeen-year-old, took a job as an apprentice Union Pacific coach painter in Pocatello, Idaho, and — because he was still a farmboy in habits and woke up each morning at five — read the Book of Mormon and The Discourses of Brigham Young in his lonely boarding room. -

Race Equity and Belonging Report

REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE BYU COMMITTEE ON Race, Equity, and Belonging FEBRUARY 2021 Report and Recommendations of the BYU Committee on Race, Equity, and Belonging Presented to President Kevin J Worthen FEBRUARY 2021 Cover photos (clockwise from top left): Andrea C., communications major; Batchlor J., communications graduate student; Kyoo K., BYU employee; Lita G., BYU employee. Dear President Worthen, In June 2020, you directed the formation of the BYU Committee on Race, Equity, and Belonging. We are grateful to have been appointed by you to serve on this important committee at this crucial time. You charged us to review processes, policies, and organizational attitudes at BYU and to “root out 1 racism,” as advised by Church President Russell M. Nelson in his joint statement with the NAACP. In setting the vision and mandate for our work, you urged us to seek strategies for historic, transformative change at BYU in order to more fully realize the unity, love, equity, and belonging that should characterize our campus culture and permeate our interactions as disciples of Jesus Christ. As a committee, we have endeavored to carry out that charge with an aspiration to build such a future at BYU. Our work has included numerous meetings with students, alumni, faculty, staff, and administrators as well as more than 500 online submissions of experiences and perspectives from members of the campus community. This effort has been revealing and has illustrated many opportunities for improvement and growth at the university. We anticipate that realizing our aspiration to bring about historic, transformative change will require a longstanding institutional commitment, searching internal reviews, and innovative thinking from each sector of the university community. -

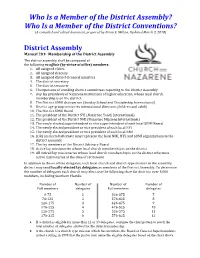

Who Is a Member of the District Assembly? Who Is a Member of the District Conventions? (A Compiled and Edited Document, Prepared by Brian E

Who Is a Member of the District Assembly? Who Is a Member of the District Conventions? (A compiled and edited document, prepared by Brian E. Wilson, Updated March 3, 2018) District Assembly Manual 201: Membership of the District Assembly The district assembly shall be composed of the following ex officio (by virtue of office) members: 1. All assigned elders 2. All assigned deacons 3. All assigned district-licensed ministers 4. The district secretary 5. The district treasurer 6. Chairpersons of standing district committees reporting to the District Assembly 7. Any lay presidents of Nazarene institutions of higher education, whose local church membership is on the district. 8. The District SDMI chairperson (Sunday School and Discipleship International) 9. District age-group ministries international directors (children and adult) 10. The District SDMI Board 11. The president of the District NYI (Nazarene Youth International) 12. The president of the District NMI (Nazarene Missions International) 13. The newly elected superintendent or vice superintendent of each local SDMI Board 14. The newly elected president or vice president of each local NYI 15. The newly elected president or vice president of each local NMI 16. (OR) an elected alternate may represent the local NMI, NYI, and SDMI organizations in the district assembly 17. The lay members of the District Advisory Board 18. Active lay missionaries whose local church membership is on the district 19. All retired lay missionaries whose local church membership is on the district who were active missionaries at the time of retirement In addition to the ex officio delegates, each local church and church-type mission in the assembly district may send locally-elected lay delegates as members of the District Assembly. -

NDS Endorsement Part 3

Part 3: Instructions for Student Commitment and Confidential Report Instructions to all Applicants: Applicants to the CES schools commit to live the ideals and principles of the gospel of Jesus Christ and to maintain the standards of conduct as taught by The Church of Jesus Christ of latter-day Saints. By accepting admission to these schools, individuals reconfirm their commitment to observe these standards. After reading this page, you must Interview With your LDS bishop or branch president. LDS applicants must also interview with a member of their current stake or district presidency. Non-LDS applicants may interview with any local LDS Bishop, then will be contacted by the university chaplain for a second interview after CES receives Part 3. Your ecclesiastical leader w1ll complete his section of Part 3 and send the entire section directly to Educational Outreach. Please sign Part 3 at the conclusion of your interview. Instructions to the Interviewing Officer: Please review in detail the Honor Code and the Dress and Grooming Standards with the applicant. The First Presidency directs ecclesiastical leaders to not endorse students with unresolved worthiness or activity problems. A student who is admitted but is not actually worthy of the ecclesiastical endorsement given is not fully prepared spiritually and displaces another student who is qualified to attend. Individuals who are 1) less active, 2) unworthy, or 3) under Church discipline should not be endorsed for admission until these issues have been completely resolved and the requisite standards of worthiness are met. If endorsed, please forward this form directly to the stake or district president. -

A Historical Examination of the Views of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and the Reorganized Church of Jesus

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1968 A Historical Examination of the Views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints on Four Distinctive Aspects of the Doctrine of Deity Taught by the Prophet Joseph Smith Joseph F. McConkie Sr. Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation McConkie, Joseph F. Sr., "A Historical Examination of the Views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter- Day Saints and the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints on Four Distinctive Aspects of the Doctrine of Deity Taught by the Prophet Joseph Smith" (1968). Theses and Dissertations. 4925. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4925 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. i A historical examination OF THE VIEWS OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTERDAYLATTER DAY SAINTS AND THE reorganized CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTERDAYLATTER DAY SAINTS ON FOUR distinctive ASPECTS OPOFTHE DOCTRINE OF DEITY TAUGHT BY THE PROPHET JOSEPH SMITH A thesis presented to the graduate studies in religious instruction brigham young