Gary A. Rendsburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Omar Ibn Said a Spoleto Festival USA Workbook Artwork by Jonathan Green This Workbook Is Dedicated to Omar Ibn Said

Omar Ibn Said A Spoleto Festival USA Workbook Artwork by Jonathan Green This workbook is dedicated to Omar Ibn Said. About the Artist Jonathan Green is an African American visual artist who grew up in the Gullah Geechee community in Gardens Corner near Beaufort, South Carolina. Jonathan’s paintings reveal the richness of African American culture in the South Carolina countryside and tell the story of how Africans like Omar Ibn Said, managed to maintain their heritage despite their enslavement in the United States. About Omar Ibn Said This workbook is about Omar Ibn Said, a man of great resilience and perseverance. Born around 1770 in Futa Toro, a rich land in West Africa that is now in the country of Senegal on the border of Mauritania, Omar was a Muslim scholar who studied the religion of Islam, among other subjects, for more than 25 years. When Omar was 37, he was captured, enslaved, and transported to Charleston, where he was sold at auction. He remained enslaved until he died in 1863. In 1831, Omar wrote his autobiography in Arabic. It is considered the only autobiography written by an enslaved person—while still enslaved—in the United States. Omar’s writing contains much about Islam, his religion while he lived in Futa Toro. In fact, many Africans who were enslaved in the United States were Muslim. In his autobiography, Omar makes the point that Christians enslaved and sold him. He also writes of how his owner, Jim Owen, taught him about Jesus. Today, Omar’s autobiography is housed in the Library of Congress. -

Torah on Tap Amalek! 2008/03/Finding -Amalek.Html

Torah on Tap Amalek! http://rabbiseinfeld.blogspot.com/ 2008/03/finding -amalek.html Genesis 36: And Esau dwelt in the mountain-land of Seir--Esau is 8 ח ַוֵּיֶׁשבֵּ עָׂשו ְּבַהֵּר שִעיר, ֵּעָׂשו הּוא .Edom ֱאדֹום. And these are the generations of Esau the father of a 9 ט ְּוֵּאֶׁלה תְֹּּלדֹותֵּ עָׂשו, ֲאִבי ֱאדֹום, .the Edomites in the mountain-land of Seir ְּבַהר, ֵּשִעיר. These are the chiefs of the sons of Esau: the sons of 15 טו ֵּאֶׁלה, ַאלֵּּופי ְּבֵּני-ֵּעָׂשו: ְּבֵּני Eliphaz the first-born of Esau: the chief of Teman, the ֱאִלַיפז, ְּבכֹורֵּ עָׂשו--ַאלֵּּוף תיָׂמן ,chief of Omar, the chief of Zepho, the chief of Kenaz ַאלּוף אָֹׂומר, ַאלְּּוף צפֹו ַאלּוףְּקַנז. the chief of Korah, the chief of Gatam, the chief of 16 טז ַאלּוף- ַקֹּרחַאלּוף ַגְּעָׂתם, Amalek. These are the chiefs that came of Eliphaz in ַאלּוףֲ עָׂמֵּלק; ֵּאֶׁלה ַאלֵּּופי ֱאִלַיפ ז .the land of Edom. These are the sons of Adah ְּבֶׁאֶׁרֱץאדֹום, ֵּאֶׁלְּה בֵּניָׂ עָׂדה. When Esau was getting old, he called in his grandson Amalek and said: "I tried to kill Jacob but was unable. Now I am entrusting you and your descendents with the important mission of annihilating Jacob's descendents -- the Jewish people. Carry out this deed for me. Be relentless and do not show mercy." (Midrashim Da’at and Hadar, summarised from Legends of the Jews volume 6 – Louis Ginzburg p.23) Exodus 17: Then came Amalek, and fought with Israel in 8 ח ַוָׂיבֹּא, ֲעָׂמֵּלק; ַוִיָׂלֶׁחםִעם- .Rephidim ִיְּשָׂרֵּאל, ִבְּרִפִידם. ,And Moses said unto Joshua: 'Choose us out men 9 ט ַויֶֹּׁאמֶׁר מֹּשה ֶׁאל-ְּיֻׁהֹושַע ְּבַח ר- and go out, fight with Amalek; tomorrow I will stand ָׂלנּו ֲאָׂנִשים, ְּוֵּצאִ הָׂלֵּחם ַבֲעָׂמֵּלק; '.on the top of the hill with the rod of God in my hand ָׂמָׂחר, ָאנִֹּכי ִנָׂצב ַעל-רֹּאשַ הִגְּבָׂעה, ַּומֵּטה ָׂהֱאלִֹּהים, ְּבָׂיִדי. -

The Unforgiven Ones

The Unforgiven Ones 1 God These are the generations of Esau (that is, Edom). 2 Esau took his wives from the Canaanites: Adah the daughter of Elon the Hittite, Oholibamah the daughter of Anah the daughter of Zibeon the Hivite, 3 and Basemath, Ishmael's daughter, the sister of Nebaioth. 4 And Adah bore to Esau, Eliphaz; Basemath bore Reuel; 5 and Oholibamah bore Jeush, Jalam, and Korah. These are the sons of Esau who were born to him in the land of Canaan. 6 Then Esau took his wives, his sons, his daughters, and all the members of his household, his livestock, all his beasts, and all his property that he had acquired in the land of Canaan. He went into a land away from his brother Jacob. 7 For their possessions were too great for them to dwell together. The land of their sojournings could not support them because of their livestock. 8 So Esau settled in the hill country of Seir. (Esau is Edom.) 9 These are the generations of Esau the father of the Edomites in the hill country of Seir. 10 These are the names of Esau's sons: Eliphaz the son of Adah the wife of Esau, Reuel the son of Basemath the wife of Esau. 11 The sons of Eliphaz were Teman, Omar, Zepho, Gatam, and Kenaz. 12 (Timna was a concubine of Eliphaz, Esau's son; she bore Amalek to Eliphaz.) These are the sons of Adah, Esau's wife. 13 These are the sons of Reuel: Nahath, Zerah, Shammah, and Mizzah. -

Study Genesis 36

A dash between two dates Intro: even though we know by now that money will not make us happy that family will not make us fulfilled and that power will not make us immortal we seem to want to find out for ourselves Problem: Ecclesiastes 2:1-11 Esau is an illustration of Solomon’s experiment - he is a man whose heart is set upon the world - as we behold his wealth, his legacy, his power, and the meaninglessness of it all, ask yourself the question…. Main Idea: what good is your wealth what good is your legacy what good is your power without God? Implication: what good is wealth without wisdom? what good is a legacy without life? what good is power without permanence? what good is any of it without God? Application: Judges 10:1-5 like all of us Esau had a dash between two dates - his wealth, his legacy and his power ultimately meant nothing more than these guys -what will yours mean? Articles to read for further study: https://www.gotquestions.org/wealth-Christian.html https://www.desiringgod.org/topics/parenting# https://www.gotquestions.org/Christian-politics.html A dash between two dates text: What good is your wealth what good is your power Gen. 36:1 ¶ These are the generations of Esau (that is, Edom). Gen. 36:15 ¶ These are the chiefs of the sons of Esau. The sons of Gen. 36:2 Esau took his wives from the Canaanites: Adah the daughter Eliphaz the firstborn of Esau: the chiefs Teman, Omar, Zepho, Kenaz, of Elon the Hittite, Oholibamah the daughter of Anah the daughter of Gen. -

Amalek from Generation to Generation

11 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Amalek from Generation Asher Benzion Buchman responds: to Generation I thank Dr. Tanen for acknowledg- I WAS DISAPPOINTED that you in- ing that my article on modern-day cluded gratuitous political posturing Amalek made “many fine points,” in your recent article Amalek From but I am puzzled as to why he then Generation to Generation (Hakiraḥ 28). finds it to include “gratuitous polit- Hakiraḥ is supposed to be “a forum ical posturing” as there is nothing for the discussion of issues of hash- gratuitous about my identification kafah and halakhah relevant to the of the base of the Democratic Party community from a perspective of with Amalek. That is the whole careful analysis of the primary To- point of the article. What could be rah sources.” The article could have more “relevant to the community” made its many fine points without than this? The purpose of Torah is the political posturing, sexism and lilmod al m’nas la’asos. Rambam iden- xenophobia: “And thus the base of tifies the eternal enemy of the Jews the Democratic Party in the United as those who either want to physi- States is made up of the envious cally annihilate the Jewish people or lower classes, the Muslims, and the to kill them spiritually by tearing G-dless ‘intellectuals’ who domi- them away from their religion. He nate and indoctrinate on our college refers to the prophecies of Daniel campuses and in the media. All are to suggest that these two groups will driven by jealousy. Jealousy and its eventually work in tandem. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE a Study of Antichrist

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE A Study of Antichrist Typology in Six Biblical Dramas of 17th Century Spain A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Spanish by Jason Allen Wells December 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. James Parr, Chairperson Dr. David Herzberger Dr. Benjamin Liu Copyright Jason Allen Wells 2014 The Dissertation of Jason Allen Wells is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A Study of Antichrist Typology in Six Biblical Dramas of 17th Century Spain by Jason Allen Wells Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Spanish University of California, Riverside, December 2014 Dr. James Parr, Chairperson This dissertation examines Antichrist types manifested in the primary antagonists of six biblical dramas of seventeenth century Spanish theater. After researching the topic of biblical typology in the works of theologians Sir Robert Anderson, G.H. Pember, Arthur W. Pink, and Peter S. Ruckman, who propose various personages of both the Old and New Testaments that adumbrate the Antichrist, I devise a reduced list based on extant plays of the Spanish Golden Age whose main characters match the scriptural counterparts of my register. These characters are Cain, Absalom, Haman, Herod the Great, Judas Iscariot, and the Antichrist himself. I consult the Bible to provide the reader with pertinent background information about these foreshadowings of the Son of Perdition and then I compare and contrast these characteristics with those provided by the playwrights in their respective works. By making these comparisons and contrasts the reader is able to observe the poets’ embellishments of the source material, artistic contributions that in many instances probably satisfy the reader’s desire for details not found in the biblical iv narratives. -

Genesis 36:15 Genesis 36

Calvary Chapel Portsmouth TheThe GenerationsGenerations ofof EsauEsau ChapterChapter 3636 - A verse by verse study of the book of Genesis Session 30 Genesis Part 1 Session Genesis 1, 2 Creation 1-8 Genesis 3 Fall of Man 9 Genesis 4 Cain & Abel 10 Genesis 5-6 Days of Noah 11 Genesis 7-8 Flood of Noah 12 Genesis 9-10 Post-Flood World 13 Genesis 11 Tower of Babel 14 Part 2 Genesis 12-20 Abraham 15, 16 Genesis 21-27 Isaac 17, 18 Genesis 28-36 Jacob 19, 20 Genesis 37-48 Joseph 21, 22, 23 Genesis 49-50 12 Tribes Prophetically 24 Genesis 36 1 Now these are the generations of Esau, who is Edom. 2 Esau took his wives of the daughters of Canaan; Adah the daughter of Elon the Hittite, and Aholibamah the daughter of Anah the daughter of Zibeon the Hivite; 3 And Bashemath Ishmael's daughter, sister of Nebajoth. Genesis 36:1-3 The Wives of Esau Hittite Hivite Ishmaelite Adah Aholibamah Bashemath “ornament” “tent of the high place” “fragrant spice” Genesis 36 4 And Adah bare to Esau Eliphaz; and Bashemath bare Reuel; 5 And Aholibamah bare Jeush, and Jaalam, and Korah: these are the sons of Esau, which were born unto him in the land of Canaan. Genesis 36:4-5 Hittite Hivite Ishmaelite Adah Aholibamah Bashemath “ornament” “tent of the high place” “fragrant spice” Eliphaz Juesh Reuel “God of gold” “hasty” “friend of God” Jaalam “consealed” Korah “pull hair out” Genesis 36 6 And Esau took his wives, and his sons, and his daughters, and all the persons of his house, and his cattle, and all his beasts, and all his substance, which he had got in the land of Canaan; and went into the country from the face of his brother Jacob. -

The Reccnnition That Knowledge About the Bible Is Fundamental To

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 049 239 TE 002 338 TITLE The Bible as Literature. INSTITUTION Broward County Board of Public Instruction, Fort Lauderdale, Fla. PUB DATE: 71 NOTZ 119p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Biblical Literature, Christianity, Cultural Background, History, Humanities, Judaism, Literature, *Literature Appreciation, Philosophy, Religion, *Secondary Education, Senior High Schools, *Study Guides, Western Civilization ABSTRACT The reccnnition that knowledge about the Bible is fundamental to understanding western cultural heritage, as well as allusions in literature, music, the fine arts, news media, and entertainment, guided the development of this elective course of study for senior high school students. Test suggestions, objectives, and lesson plans are provided for each of the 0.ght units: (1) Introduction and Historical Background; (2) The Apocrypha; (3) Biography and History As Literature in the New Testament; CO The Narrative; (5) Poetry in the Bible;(6) Wisdom Literature; (7) Drama--the Book of Job; and (8)Prophetic Literature of the Bible. Lesson plans within these units include goals, readings, and activities. A bibliography plus lists of audiovisual materials, film strips, and transparencies conclude this guide. (JMC) U.S. DEPARTMENT Of HEALTH, EDUCATION I WELFARE 0 OFFICE Of EDUCATION THIS DOCIIMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON 01 ORGARIEATION ORIGINATING If PONT; Of CM OR ONIONS sun DO NOT NECESSAR'lf REPRESENT OffICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POLITION OR POLICY 01 THE BIBLE AS LITERATURE THE SCHOOL BOARD OF BROWARD COUNTY, FLORIDA Benjamin C. Willis, Superintendent of Schoo's THE BIBLE AS LITERATURE THE SCHOOL BOARD OF BROWARD COUNTY, FLORIDA Benjamin C. -

36:9–19 (ESV) of Their Livestock

These are the generations of Esau the father of the Edomites in the hill country of Seir. These are the names of Esau’s sons: Eliphaz the son of Adah the wife of Esau, Reuel the son of Basemath the wife of Esau. The sons of Eliphaz were Teman, Omar, Zepho, Gatam, and Kenaz. (Timna was a concubine of Eliphaz, July 10, 2016 Esau’s son; she bore Amalek to Eliphaz.) These are the sons of Adah, Esau’s wife. These are the sons of Reuel: Nahath, Zerah, Shammah, and Mizzah. These are the sons of Basemath, Esau’s wife. These are the sons of These are the generations of Esau (that is, Edom). Esau took his wives from the Oholibamah the daughter of Anah the daughter of Zibeon, Esau’s wife: she bore Canaanites: Adah the daughter of Elon the Hittite, Oholibamah the daughter of to Esau Jeush, Jalam, and Korah. These are the chiefs of the sons of Esau. The Anah the daughter of Zibeon the Hivite, and Basemath, Ishmael’s daughter, the sons of Eliphaz the firstborn of Esau: the chiefs Teman, Omar, Zepho, Kenaz, sister of Nebaioth. And Adah bore to Esau, Eliphaz; Basemath bore Reuel; and Korah, Gatam, and Amalek; these are the chiefs of Eliphaz in the land of Edom; Oholibamah bore Jeush, Jalam, and Korah. These are the sons of Esau who these are the sons of Adah. These are the sons of Reuel, Esau’s son: the chiefs were born to him in the land of Canaan. Then Esau took his wives, his sons, his Nahath, Zerah, Shammah, and Mizzah; these are the chiefs of Reuel in the land daughters, and all the members of his household, his livestock, all his beasts, of Edom; these are the sons of Basemath, Esau’s wife. -

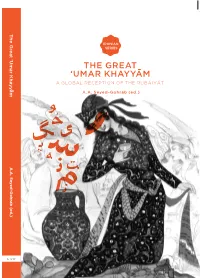

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

The Book of Genesis

The book of Genesis 01_CEB_Childrens_Genesis.indd 1 8/21/14 3:23 PM CEB Deep Blue Kids Bible © 2012 by Common English Bible “Bible Basics” is adapted from Learning to Use My Bible—Teachers Guide by Joyce Brown ©1999 Abingdon Press. “Discovery Central” dictionary is adapted from Young Reader’s Bible Dictionary, Revised Edition © 2000 Abingdon Press. All rights reserved on Deep Blue Notes, Life Preserver Notes, God Thoughts/My Thoughts, Did You Know?, Bet You Can!, and Navigation Point! material. No part of these works may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may expressly be permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act, the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act, or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Common English Bible, 2222 Rosa L. Parks Boulevard, Nashville, TN 37228-1306, or e-mailed to permissions@ commonenglish.com. Copyright © 2011 by Common English Bible The CEB text may be quoted and/or reprinted up to and inclusive of five hundred (500) verses without express written permission of the publisher, provided the verses quoted do not amount to a complete book of the Bible nor account for twenty-five percent (25%) of the written text of the total work in which they are quoted. Notice of copyright must appear on the title or copyright page of the work as follows: “All scripture quotations unless noted otherwise are taken from the Common English Bible, copyright 2011. Used by permission. -

Genesis 36 2 of 13

Genesis (2011) 36 • Having reached the end of Isaac’s toldat, we reach an interlude with chapter 36 o The next toldat we will study will be the toldat of Jacob § Speci!cally, we’ll study the story of his children § The book of Genesis contains 10 toldots or genealogies altogether § This chapter gives us the ninth toldat o Let’s remember that the story of Genesis isn’t concerned with telling an interesting story or documenting the lives of interesting people § It is a very interesting story and it does revolve around some very interesting people § But Genesis is a story of Man’s creation, fall and God’s response to that fall • The response of God was to promise a Seed Who would come into the world to save Creation from the fall • That Seed is Jesus Christ § So in Genesis we’re focused on the stories of those who are connected in some way to God’s ful!llment of His promise • Obviously, the patriarchs are important to the ful!llment of that promise • Abraham, Isaac and Jacob are men who produce the nation of Israel • And Israel will be the people to bring the Messiah into the world • With Abraham and Isaac, Moses focused on which of two possible heirs received the seed promise o In the case of Abraham, Isaac received the promise and in the case of Isaac, Jacob received the promise § But in both cases, Moses allotted a chapter to bringing to an end the story of the rejected son © 2012 – Verse By Verse Ministry International (www.versebyverseministry.org) May be copied and distributed provided the document is reproduced in its entirety, including this copyright statement, and no fee is collected for its distribution.