Home Is the Hunter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

65Yearsbook.Pdf

yorkton film festival 65 Years of film 1 Table of Contents 1937 – 1947: Beginnings – The Yorkton Film Council ……………………………………………………………………………2 1947 – 1960: The Yorkton Film Council Goes to Work ……………………………………………………………………………4 The Projectionist – Then and Now ……………………………………………………………………………6 The 1950s: Yorkton Film Council Screenings – Indoors and Out ……………………………………………………………………………7 1955: Good on You, Yorkton ……………………………………………………………………………9 1947: The Formation of the International Film Festival ……………………………………………………………………………10 1950s: The First International Festival ……………………………………………………………………………11 1952: The Ongoing Story ……………………………………………………………………………13 1954: Why Not Yorkton? ……………………………………………………………………………14 1950 – 1954: The People’s Choice ……………………………………………………………………………15 1956: The Russians Are Coming ……………………………………………………………………………16 1957: Fire! ……………………………………………………………………………18 1957: National Recognition ……………………………………………………………………………20 1960s: An End and a Beginning ……………………………………………………………………………20 1969 – 1979: Change ……………………………………………………………………………21 1969 – 1979: Change – Film, Food, and Fun ……………………………………………………………………………26 1969 – 1979: Change – “An Eyeball Blistering Task” ……………………………………………………………………………26 1969 – 1979: Change – The Cool Cats ……………………………………………………………………………28 1969 – 1979: Change – Money was a Good Thing! It Still Is… ……………………………………………………………………………29 1969 – 1979: Change – Learning the Trade ……………………………………………………………………………31 1971: A Message to Venice ……………………………………………………………………………32 1958 and 1977: The Golden Sheaf ……………………………………………………………………………33 -

Mapping Past and Future Wars in Voice of the People: Experiencing Narrative in the 3D/VR Environment Institution: Florida Atlantic University

Mapping Past and Future Wars in Voice of the People: Experiencing Narrative in the 3D/VR Environment by Ivan Kalytovskyy A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL August 2017 Copyright by Ivan Kalytovskyy 2017 ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere thanks to Dr. Joey Bargsten for his unrelenting support and encouragement throughout the writing of this manuscript. Additionally, I would like to thank professor Francis X. McAfee for his continued support throughout my undergraduate and graduate studies, his advice and orientation has inspired me to tackle any challenge. Additionally, Bradley Lewter for his advice in navigating the challenges of this project. I am also grateful to Dr. Eric Freedman and Dr. Noemi Marin for providing me with teaching assistantship that greatly lifted the financial burdens of my education. iv ABSTRACT Author: Ivan Kalytovskyy Title: Mapping Past and Future Wars in Voice of the People: Experiencing Narrative in the 3D/VR Environment Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Bradley Lewter Degree: Master of Fine Arts Year: 2017 We have an opportunity not only to interact with 3D content but also to immerse ourselves in it via Virtual Reality (VR). This work is deeply inspired by my experience as a Ukrainian witnessing the recent turmoil in my homeland. I wanted people around the globe to experience the horrors that are unfolding. The Voice of the People, explores narrative storytelling through VR. -

FILMS on ICE Cinemas of the Arctic

FILMS ON ICE Cinemas of the Arctic Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport MACKENZIE 9780748694174 PRINT (MAD0040) (G).indd 3 31/10/2014 14:39 © editorial matter and organisation Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport, 2014 © the chapters their several authors, 2014 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 10/12.5 pt Sabon by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9417 4 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9418 1 (webready PDF) The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). MACKENZIE 9780748694174 PRINT (MAD0040) (G).indd 4 31/10/2014 14:39 CONTENTS List of Illustrations viii Acknowledgements xi Introduction: What are Arctic Cinemas? 1 Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport PART I GLOBAL INDIGENEITY 1. ‘Who Were We? And What Happened to Us?’: Inuit Memory and Arctic Futures in Igloolik Isuma Film and Video 33 Marian Bredin 2. Northern Exposures and Marginal Critiques: The Politics of Sovereignty in Sámi Cinema 45 Pietari Kääpä 3. Frozen in Film: Alaska Eskimos in the Movies 59 Ann Fienup-Riordan 4. Cultural Stereotypes and Negotiations in Sámi Cinema 72 Monica Kim Mecsei 5. Cinema of Emancipation and Zacharias Kunuk’s Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner 84 Marco Bohr MACKENZIE 9780748694174 PRINT (MAD0040) (G).indd 5 31/10/2014 14:39 FILMS ON ICE 6. -

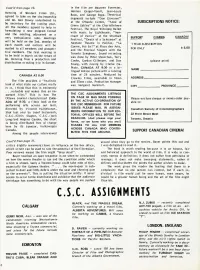

C.S.C. ASSIGNMENTS

Cont'd from page 13. in the film are Maureen Forrester, Herman Geiger-Tore II, Jean-Louis Henning of Western Fi Ims Ltd., Roux, and George Ryga. Theatrical agreed to take on the chairmanship segments inc lude "Don Giovanni" and Mr. Ken Davey volunteered to at the O'Keefe Centre, "Anne of SUBSCRIPTIONS NOTICE: be secretary for the coming year. Green Gab les" at the Char lottetown All the members agreed to help in Festival, The Royal Winnipeg Ballet formulating a new program format with music by Lighthouse, "Mer and the meeting adjourned on a chant of Venice" at the Stratford very enthusiastic note. Meetings SUPPORT CINEMA CANADA! Festiva I, "Death of a Sa lesman" at will be held on the 2nd. MOf.1day of Neptune Theatre in Halifax, "La 1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION eac h month and not ices will be Guerre, Yes Sir!" at Place des Arts, FOR ONLY $ 5.00 mailed to all members and prospec and the Festival Singers with the tive members. The first meeting is Toronto Symphony. Sound recording to be he Id in Marc h on the return of was done by Peter Shewc huk, Terry Mr. Henning from a production and Cooke, Gordon Gillespie. and Don (p lease pr i nt) distribution scouting trip in Europe. Young, with mixing by Clarke Da Prato. CANADA AT 8:30 is a bi NAME _ lingual motion picture with a running time of 28 minutes. Produced by CANADA AT 8:30 ADDRESS _ Crawley ,Films, available in 16mm The film provides a "realistic and 35mm color. -

Curriculum Vitae Professor Adrian Tanner

CURRICULUM VITAE PROFESSOR ADRIAN TANNER Personal Information Name: Adrian Tanner Current Position: Honorary Research Professor University Address: Centre for Aboriginal Research, Inco Innovation Centre, Department of Anthropology, Memorial University, St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada, A1C 5S7. Home Address: Box 159, Petty Harbour, Newfoundland, A0A 3H0 Phone: (709) 737-8868; Home: 368-8614 Fax: (709) 737-8686 E-mail: [email protected] Born: London, England; 31 October 1937 Citizenship: Canadian (Immigrated 1955, Naturalized 1968) Education Secondary: Latymer Upper, London, U.K. (GCE 1954) Undergraduate: University of British Columbia (BA 1964, Anthropology and Geography) Graduate: University of British Columbia (MA 1966, Anthropology) University of Toronto (Ph.D. 1976, Anthropology) Theses 1976 ‘Bringing Home Animals. Religious Ideology and Mode of Production of the Mistassini Cree Hunters.’ Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto. 1966 ‘The Structure of Fur Trade Relations in the Yukon Territory.’ MA Thesis, University of B.C. Languages English (Mother tongue) French (Reading, speaking and oral comprehension - good; writing - fair) Cree, Mistassini dialect (basic conversational) Fijian, Western Interior Viti Levu dialect (limited conversational) Innuktitut, Iniksuak, PQ dialect (very limited conversational) University Employment 1971-72: Part-time Lecturer, Anthropology, University of Toronto (Scarborough College) 1972-74: Lecturer, Anthropology, Memorial University 2 1974-80: Assistant Professor, Anthropology, Memorial University 1980-87: Associate Professor, Anthropology, Memorial University 1987-2003: Professor, Anthropology, Memorial University Awards and Distinctions. 2013. Awarded the Weaver-Tremblay medal in Applied Anthropology. Canadian Anthropology Society. 1999-2000: Russel Visiting Professor of Native American Studies, Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, USA. Publications Books 2014 Bringing Home Animals. Mistissini Hunters of Northern Quebec. (A revised and augmented edition of 1979, below). -

David Blackwood Fonds LA.SC152

E.P. Taylor Library & Archives Description and Finding Aid: David Blackwood Fonds LA.SC152 Prepared by Hannah Johnston, 2018 317 Dundas Street West, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5T 1G4 Reference Desk: 416-979-6642 www.ago.ca/library-archives David Blackwood Fonds David Blackwood Fonds Dates of creation: 1900-2017 Extent: 5.2 m of textual records and graphic material 1773 photographs (1638 prints, 132 negatives, 3 slides) 21 certificates and awards on paper 12 drawings 6 sketchbooks 6 videocassettes 3 posters 1 film reel 1 map 1 DVD Biographical sketch: David Blackwood (1941- ) is a Canadian artist known for his prints depicting Newfoundland life and culture. Born in Wesleyville, Newfoundland in 1941, Blackwood was exposed to subjects which influenced the themes represented in his art: fishermen and sealers and their families; relationships with the land; harsh landscapes; and the importance of tradition to communities on Canada’s east coast. Blackwood attended the Ontario College of Art from 1959-1963, where he studied printmaking. Subsequently, he was the first artist-in-residence at Erindale College at University of Toronto Mississauga, from 1969 to 1975. The Erindale College Art Gallery was renamed The Blackwood Gallery in 1992 in the artist’s honour. In 1976, Blackwood was the subject of a documentary produced by the National Film Board of Canada – titled Blackwood – which was nominated for an Academy Award. Blackwood was a member of the AGO Board of Trustees and the Inuit Art Foundation in Ottawa. He was also the recipient of numerous other awards and accolades, including honorary doctorates at the University of Calgary and Memorial University of Newfoundland (1992); a National Heritage Award (1993); the Order of Ontario (2002); and the Order of Canada (1993). -

Major Developments This Cabinet Area

nEWS Major Developments this cabinet area. No explanation was mISSIOn, but right now they've got given, but Minister of Industry and something slightly more important to It's sort of like some weird circle Tourism Claude Bennett did visit consider, for on April 10 the Quebec action, if you examine the develop Hollywood recently to promote Ont government introduced its long ment of the film industry over the past ario as a movie-making place. Bennett awaited film law, loi cadre. And the several years. The federal government said he wanted Hollywood money and reaction by the industry was anything sets up the CFDC to aid in establishing Ontario talent, whereupon some MP's but gleeful. Cultural Affairs Minister the industry; the filmmakers become suggested it might be a better idea to Denis Hardy presented a bill that will very active, first in actual movie get some Ontario movies made and to have widespread effects on Quebec making, and then politically as prob institute quotas. As a matter of fact, film making and showing. lems arise in forming a solid industrial Ontario has been the great hold-out in The bill first abolishes the present base. Now it's the provinces' turn, as the quota question; Premier William Cinema Advisory Board and substi the assault on their jurisdictions - Davis has said publicly that he's tutes a Quebec Film Institute and mainly in quotas and financial aid - opposed to it, and without Ontario Cinema Classification Board, directly begins. And of course they'll act with there's no point in pushing a national under the minister; the former body the federal government to co-ordinate quota; most box office income is from was separate from the ministry, any efforts. -

The Info-Immersive Modalities of Film Documentarian and Inventor Roman Kroitor

The Info-Immersive Modalities of Film Documentarian and Inventor Roman Kroitor by Graeme Hamish Langdon A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Information Faculty of Information University of Toronto © Copyright by Graeme Hamish Langdon 2012 The Info-Immersive Modalities of Film Documentarian and Inventor Roman Kroitor Graeme Hamish Langdon Master of Information Faculty of Information University of Toronto 2012 Abstract In this thesis, it is argued that Canadian film documentarian and inventor Roman Kroitor’s lifework is structured by simultaneous appeals to the realist and reflexive capacities of film and animation. It is shown that the diverse periods in Kroitor’s lifework (including documentary film production at the National Film Board of Canada; co-invention and development of the large-format film apparatus, IMAX; and software design for computer animation in stereoscopic 3D) are united by a general interest in facilitating immersive audience experiences with documentary information and evidentiary entertainment. Against those who have conceptualized cinema as functioning like a frame or a window, this thesis analyzes Kroitor’s diverse work in relation to Gene Youngblood’s conception of “expanded cinema” (1970). It is argued that Kroitor’s efforts in film and invention constitute modalities that actively eschew the architectonic limits that typically characterize the cinematic experience. ii Acknowledgments The realization of this thesis would not have been possible without the assistance I received from a number of people. First, I would like to thank my supervisor, Juris Dilevko, for his encouragement throughout the project. Second, I would like to thank my examining committee, David Harris Smith and Neil Narine, for their interest in the project and their insightful comments. -

Research and Communication

Research and Communication Suggested Films The films listed below have been suggested by Alberta teachers as useful. The Suggested Films have been divided into two sections to indicate those films that have been authorized by Alberta Education and those that have not. Note: The listing of unauthorized resources is not to be taken as explicit or implicit departmental approval for use. The titles have been provided as a service only, to help school authorities identify resources that contain potentially useful ideas. The responsibility to evaluate these resources prior to selection rests with the user, in accordance with any existing local policy. The user is also responsible for evaluating any materials listed within the resource itself. Alberta Education Authorized Films Mi’kmaq Family–Migmaoei Otjiosog. Dir. Catherine Anne Martin (Mi’kmaw). National Film Board of Canada, 1994 (33 min). The filmmaker explores her Mi’kmaw heritage at the community’s annual gathering in Nova Scotia. The Little Trapper. Dir. Dorothy Schreiber. National Film Board of Canada, 1999 (24 min). Robert Grandjambe, Jr., is a 13-year-old with a passion to learn more about traditional Cree hunting and beliefs. The Washing of Tears. Dir. Hugh Brody. National Film Board of Canada, 1994 (55 min). The Mowachahts of British Columbia express concern for their sacred whaling shrine, now housed in a major museum. Today is a Good Day: Remembering Chief Dan George. Dir. Loretta Todd (Cree Métis). Moving Images Distribution, 1998 (44 min). This video presents an intimate view of legendary actor Chief Dan George. Yuxweluptun: Man of Masks. Dir. Dana Claxton (Hunkpapa Lakota). -

William F. E. Morley Poster Collection

William F. E. Morley Poster Collection 1890-2012, n.d. RG 588 Brock University Archives Creator: Morley, William F. E. Extent: 1467 posters Abstract: The collection consists of a wide variety of popular culture posters. Topics include books, performing arts, film and television, libraries, museums, food and beverages, government and politics, lecture series, sporting events, travel, Niagara, Kingston, United Empire Loyalists and war/military. Materials: Posters Repository: Brock University Archives Processed by: Edie Williams and Chantal Cameron Last updated: June 2017 ______________________________________________________________________________ Terms of Use: The William F. E. Morley Poster Collection is open for research. Use Restrictions: Current copyright applies. In some instances, researchers must obtain the written permission of the holder(s) of copyright and the Brock University Archives before publishing quotations from materials in the collection. Most papers may be copied in accordance with the Library's usual procedures unless otherwise specified. Preferred Citation: RG 588 William F. E. Morley Poster Collection, 1890-2012, n.d., Brock University Archives, Brock University. ___________________________________________________________________________ Scope and Content: The collection consists of 1467 popular culture posters. The posters cover a wide variety of areas, including books, performing arts, film and television, libraries, museums, food and beverages, government and politics, lecture series, sporting events, travel, Niagara, Kingston, United Empire Loyalists and war/military. ______________________________________________________________________________ RG 588 Page 2 Organization: The records were arranged into twelve series: Series I. Book promotions / Printing, 1969-2011, n.d. Series II. Arts and Culture, 1930-2011,n.d. Sub-Series A. Art, 1930-1992, n.d. Sub-Series B. Dance, 1985-2003, n.d. Sub-Series C. -

The World of 3D Movies” by Eddie Sammons 12 September 2005

THE WORLD OF 3-D MOVIES Eddie Sammons Copyright 0 1992 by Eddie Sammons. A Delphi Publication. Please make note of this special copyright notice for this electronic edition of “The World of 3-D Movies” downloaded from the virtual library of the Stereoscopic Displays and Applications conference website (www.stereoscopic.org): Copyright 1992 Eddie Sammons. All rights reserved. This copy of the book is made available with the permission of the author for non-commercial purposes only. Users are granted a limited one-time license to download one copy solely for their own personal use. This edition of “The World of 3-D Movies” was converted to electronic format by Andrew Woods, Curtin University of Technology. C 0 N T E N T S. Page PROLOGUE - Introduction to the book and its contents. 1 CHAPTER 1 - 3-D. - -..THE FORMATS 2 Hopefully, the only boring part of the book but necessary if you, the reader, are to understand the technical terms. CHAPTER 2 - 3-D ..... IN THE BEGINNING .... AND NOW 5 A brief look at the history of stereoscopy with particular regard to still photography. CHAPTER 3 - 3-D ....OR NOT 3-D 12 A look at some at some of the systems that tried to be stereoscopic, those that were but not successfully so and some off-beat references to 3-D. CHAPTER 4 - 3-D. - -.- THE MOVIES, A CHRONOLOGY 25 A brief history of 3-D movies, developments in filming and presentation, festivals and revivals - CHAPTER 5 - 3-D. -..THE MOVIES 50 A filmography of all known films made in 3-D with basic credits; notation of films that may have been made in 3-D and correction of various misconceptions; cross-references to alternative titles, and possible English translations of titles; cross-reference to directors of the films listed.