INFORMATION Ta USERS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Digital Movies As Malaysian National Cinema A

Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Hsin-ning Chang April 2017 © 2017 Hsin-ning Chang. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema by HSIN-NING CHANG has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Erin Schlumpf Visiting Assistant Professor of Film Studies Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT CHANG, HSIN-NING, Ph.D., April 2017, Interdisciplinary Arts Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema Director of dissertation: Erin Schlumpf This dissertation argues that the alternative digital movies that emerged in the early 21st century Malaysia have become a part of the Malaysian national cinema. This group of movies includes independent feature-length films, documentaries, short and experimental films and videos. They closely engage with the unique conditions of Malaysia’s economic development, ethnic relationships, and cultural practices, which together comprise significant understandings of the nationhood of Malaysia. The analyses and discussions of the content and practices of these films allow us not only to recognize the economic, social, and historical circumstances of Malaysia, but we also find how these movies reread and rework the existed imagination of the nation, and then actively contribute in configuring the collective entity of Malaysia. 4 DEDICATION To parents, family, friends, and cats in my life 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Prof. -

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation

The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation By Jisung Catherine Kim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kristen Whissel, Chair Professor Mark Sandberg Professor Elaine Kim Fall 2013 The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation © 2013 by Jisung Catherine Kim Abstract The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation by Jisung Catherine Kim Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Kristen Whissel, Chair In The Intimacy of Distance, I reconceive the historical experience of capitalism’s globalization through the vantage point of South Korean cinema. According to world leaders’ discursive construction of South Korea, South Korea is a site of “progress” that proves the superiority of the free market capitalist system for “developing” the so-called “Third World.” Challenging this contention, my dissertation demonstrates how recent South Korean cinema made between 1998 and the first decade of the twenty-first century rearticulates South Korea as a site of economic disaster, ongoing historical trauma and what I call impassible “transmodernity” (compulsory capitalist restructuring alongside, and in conflict with, deep-seated tradition). Made during the first years after the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the films under consideration here visualize the various dystopian social and economic changes attendant upon epidemic capitalist restructuring: social alienation, familial fragmentation, and widening economic division. -

MADE in HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED by BEIJING the U.S

MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence 1 MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION 1 REPORT METHODOLOGY 5 PART I: HOW (AND WHY) BEIJING IS 6 ABLE TO INFLUENCE HOLLYWOOD PART II: THE WAY THIS INFLUENCE PLAYS OUT 20 PART III: ENTERING THE CHINESE MARKET 33 PART IV: LOOKING TOWARD SOLUTIONS 43 RECOMMENDATIONS 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 53 ENDNOTES 54 Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ade in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing system is inconsistent with international norms of Mdescribes the ways in which the Chinese artistic freedom. government and its ruling Chinese Communist There are countless stories to be told about China, Party successfully influence Hollywood films, and those that are non-controversial from Beijing’s warns how this type of influence has increasingly perspective are no less valid. But there are also become normalized in Hollywood, and explains stories to be told about the ongoing crimes against the implications of this influence on freedom of humanity in Xinjiang, the ongoing struggle of Tibetans expression and on the types of stories that global to maintain their language and culture in the face of audiences are exposed to on the big screen. both societal changes and government policy, the Hollywood is one of the world’s most significant prodemocracy movement in Hong Kong, and honest, storytelling centers, a cinematic powerhouse whose everyday stories about how government policies movies are watched by millions across the globe. -

65Yearsbook.Pdf

yorkton film festival 65 Years of film 1 Table of Contents 1937 – 1947: Beginnings – The Yorkton Film Council ……………………………………………………………………………2 1947 – 1960: The Yorkton Film Council Goes to Work ……………………………………………………………………………4 The Projectionist – Then and Now ……………………………………………………………………………6 The 1950s: Yorkton Film Council Screenings – Indoors and Out ……………………………………………………………………………7 1955: Good on You, Yorkton ……………………………………………………………………………9 1947: The Formation of the International Film Festival ……………………………………………………………………………10 1950s: The First International Festival ……………………………………………………………………………11 1952: The Ongoing Story ……………………………………………………………………………13 1954: Why Not Yorkton? ……………………………………………………………………………14 1950 – 1954: The People’s Choice ……………………………………………………………………………15 1956: The Russians Are Coming ……………………………………………………………………………16 1957: Fire! ……………………………………………………………………………18 1957: National Recognition ……………………………………………………………………………20 1960s: An End and a Beginning ……………………………………………………………………………20 1969 – 1979: Change ……………………………………………………………………………21 1969 – 1979: Change – Film, Food, and Fun ……………………………………………………………………………26 1969 – 1979: Change – “An Eyeball Blistering Task” ……………………………………………………………………………26 1969 – 1979: Change – The Cool Cats ……………………………………………………………………………28 1969 – 1979: Change – Money was a Good Thing! It Still Is… ……………………………………………………………………………29 1969 – 1979: Change – Learning the Trade ……………………………………………………………………………31 1971: A Message to Venice ……………………………………………………………………………32 1958 and 1977: The Golden Sheaf ……………………………………………………………………………33 -

Cinema in Cuban National Development: Women and Film Making Culture Michelle Spinella

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 Cinema in Cuban National Development: Women and Film Making Culture Michelle Spinella Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION CINEMA IN CUBAN NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT: WOMEN AND FILM MAKING CULTURE By MICHELLE SPINELLA A dissertation submitted to the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2004 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Michelle Spinella defended on October 6, 2003. Vandra Masemann Professor Directing Dissertation John Mayo Outside Committee Member Michael Basile Committee Member Steve Klees Committee Member Approved: Carolyn Herrington, Chair, Educational Leadership and Policy Studies The office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii Dedicated to the Beloved iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many people to thank for the considerable support I received during my graduate studies and the completion of this dissertation. Vandra Masemann, whose indefatigable patience and generosity to stay the course with me as my major professor even after leaving Florida State University, is the principle reason I have been able to finish this degree. I would like to express great gratitude to all the members of my committee who each helped in his special way, John Mayo and Steve Klees; and especially to Michael Basile, for his “wavelength.” I’d like to thank Sydney Grant for his critical interventions in helping me get to Cuba, to Emanuel Shargel for the inspiration of his presence and Mia Shargel for the same reason plus whatever she put in the tea to calm my nerves. -

LES SILENCES DU PALAIS and INCENDIES Anna Bernard

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository FRAMING PERCEPTIONS OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN FILM: LES SILENCES DU PALAIS AND INCENDIES Anna Bernard-Hoverstad A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Romance Language (French). Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Dominique D. Fisher Sahar Amer Martine Antle ABSTRACT ANNA BERNARD-HOVERSTAD: Framing Perceptions of Violence against Women in Film: Les Silences du Palais and Incendies (Under the direction of Dominique D. Fisher) This thesis focuses on how contemporary Francophone films visually represent violence against women, and explores how sexual violence functions to continue the subjugation and systematic victimization of women. I examine how Moufida Tlatli’s Les Silences du Palais and Denis Villeneuve’s Incendies approach the subject and portrayal of rape within the greater narrative of the film. The two films, quite different in their premise and setting, find commonality as they both treat and depict rape and family dynamics. As such, my goal is to evaluate how the historical contexts of the films affect the portrayal of the violent act and how it is committed, and I consider questions about the viewer’s perceptions of the perpetrators intentions might nuance their reactions to the rape scene, as well as to the film as a whole. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………1 2. Les Silences du Palais………………………………………………………………13 3. Incendies…………………………………………………………………………....30 4. -

LES SILENCES DU PALAIS and INCENDIES Anna Bernard

FRAMING PERCEPTIONS OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN FILM: LES SILENCES DU PALAIS AND INCENDIES Anna Bernard-Hoverstad A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Romance Language (French). Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Dominique D. Fisher Sahar Amer Martine Antle ABSTRACT ANNA BERNARD-HOVERSTAD: Framing Perceptions of Violence against Women in Film: Les Silences du Palais and Incendies (Under the direction of Dominique D. Fisher) This thesis focuses on how contemporary Francophone films visually represent violence against women, and explores how sexual violence functions to continue the subjugation and systematic victimization of women. I examine how Moufida Tlatli’s Les Silences du Palais and Denis Villeneuve’s Incendies approach the subject and portrayal of rape within the greater narrative of the film. The two films, quite different in their premise and setting, find commonality as they both treat and depict rape and family dynamics. As such, my goal is to evaluate how the historical contexts of the films affect the portrayal of the violent act and how it is committed, and I consider questions about the viewer’s perceptions of the perpetrators intentions might nuance their reactions to the rape scene, as well as to the film as a whole. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………1 2. Les Silences du Palais………………………………………………………………13 3. Incendies…………………………………………………………………………....30 -

Mapping Past and Future Wars in Voice of the People: Experiencing Narrative in the 3D/VR Environment Institution: Florida Atlantic University

Mapping Past and Future Wars in Voice of the People: Experiencing Narrative in the 3D/VR Environment by Ivan Kalytovskyy A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL August 2017 Copyright by Ivan Kalytovskyy 2017 ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere thanks to Dr. Joey Bargsten for his unrelenting support and encouragement throughout the writing of this manuscript. Additionally, I would like to thank professor Francis X. McAfee for his continued support throughout my undergraduate and graduate studies, his advice and orientation has inspired me to tackle any challenge. Additionally, Bradley Lewter for his advice in navigating the challenges of this project. I am also grateful to Dr. Eric Freedman and Dr. Noemi Marin for providing me with teaching assistantship that greatly lifted the financial burdens of my education. iv ABSTRACT Author: Ivan Kalytovskyy Title: Mapping Past and Future Wars in Voice of the People: Experiencing Narrative in the 3D/VR Environment Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Bradley Lewter Degree: Master of Fine Arts Year: 2017 We have an opportunity not only to interact with 3D content but also to immerse ourselves in it via Virtual Reality (VR). This work is deeply inspired by my experience as a Ukrainian witnessing the recent turmoil in my homeland. I wanted people around the globe to experience the horrors that are unfolding. The Voice of the People, explores narrative storytelling through VR. -

FILMS on ICE Cinemas of the Arctic

FILMS ON ICE Cinemas of the Arctic Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport MACKENZIE 9780748694174 PRINT (MAD0040) (G).indd 3 31/10/2014 14:39 © editorial matter and organisation Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport, 2014 © the chapters their several authors, 2014 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 10/12.5 pt Sabon by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9417 4 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9418 1 (webready PDF) The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). MACKENZIE 9780748694174 PRINT (MAD0040) (G).indd 4 31/10/2014 14:39 CONTENTS List of Illustrations viii Acknowledgements xi Introduction: What are Arctic Cinemas? 1 Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport PART I GLOBAL INDIGENEITY 1. ‘Who Were We? And What Happened to Us?’: Inuit Memory and Arctic Futures in Igloolik Isuma Film and Video 33 Marian Bredin 2. Northern Exposures and Marginal Critiques: The Politics of Sovereignty in Sámi Cinema 45 Pietari Kääpä 3. Frozen in Film: Alaska Eskimos in the Movies 59 Ann Fienup-Riordan 4. Cultural Stereotypes and Negotiations in Sámi Cinema 72 Monica Kim Mecsei 5. Cinema of Emancipation and Zacharias Kunuk’s Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner 84 Marco Bohr MACKENZIE 9780748694174 PRINT (MAD0040) (G).indd 5 31/10/2014 14:39 FILMS ON ICE 6. -

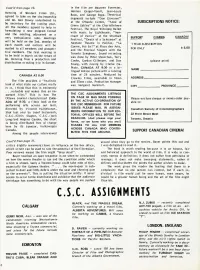

C.S.C. ASSIGNMENTS

Cont'd from page 13. in the film are Maureen Forrester, Herman Geiger-Tore II, Jean-Louis Henning of Western Fi Ims Ltd., Roux, and George Ryga. Theatrical agreed to take on the chairmanship segments inc lude "Don Giovanni" and Mr. Ken Davey volunteered to at the O'Keefe Centre, "Anne of SUBSCRIPTIONS NOTICE: be secretary for the coming year. Green Gab les" at the Char lottetown All the members agreed to help in Festival, The Royal Winnipeg Ballet formulating a new program format with music by Lighthouse, "Mer and the meeting adjourned on a chant of Venice" at the Stratford very enthusiastic note. Meetings SUPPORT CINEMA CANADA! Festiva I, "Death of a Sa lesman" at will be held on the 2nd. MOf.1day of Neptune Theatre in Halifax, "La 1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION eac h month and not ices will be Guerre, Yes Sir!" at Place des Arts, FOR ONLY $ 5.00 mailed to all members and prospec and the Festival Singers with the tive members. The first meeting is Toronto Symphony. Sound recording to be he Id in Marc h on the return of was done by Peter Shewc huk, Terry Mr. Henning from a production and Cooke, Gordon Gillespie. and Don (p lease pr i nt) distribution scouting trip in Europe. Young, with mixing by Clarke Da Prato. CANADA AT 8:30 is a bi NAME _ lingual motion picture with a running time of 28 minutes. Produced by CANADA AT 8:30 ADDRESS _ Crawley ,Films, available in 16mm The film provides a "realistic and 35mm color. -

Disparities for Women Filmmakers in the Film Industry Bobbie Lucas

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2015 Behind Every Great Man There Are More Men: Disparities for Women Filmmakers in the Film Industry Bobbie Lucas Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Lucas, Bobbie, "Behind Every Great Man There Are More Men: Disparities for Women Filmmakers in the Film Industry" (2015). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 387. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vassar College “Behind Every Great Man There Are More Men:” Disparities for Women Filmmakers in the Film Industry A research thesis submitted to The Department of Film Bobbie Lucas Fall 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS “Someday hopefully it won’t be necessary to allocate a special evening [Women in Film] to celebrate where we are and how far we’ve come…someday women writers, producers, and crew members will be so commonplace, and roles and salaries for actresses will outstrip those for men, and pigs will fly.” --Sigourney Weaver For the women filmmakers who made films and established filmmaking careers in the face of adversity and misogyny, and for those who will continue to do so. I would like to express my appreciation to the people who helped me accomplish this endeavor: Dara Greenwood, Associate Professor of Psychology Paul Johnson, Professor of Economics Evsen Turkay Pillai, Associate Professor of Economics I am extremely grateful for the valuable input you provided on my ideas and your willing assistance in my research.