Tsai Ming Liang and Re-Thinking Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: the Politics of Reading Between East and East a Dissertati

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: The Politics of Reading Between East and East A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Alvin Ka Hin Wong Committee in Charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Lowe, Co-Chair Professor Patrick Anderson Professor Rosemary Marangoly George Professor Larissa N. Heinrich 2012 Copyright Alvin Ka Hin Wong, 2012 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Alvin Ka Hin Wong is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page …………………………………………………….……………….….…iii Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………..…….…iv List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………….…........v Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………….....vi Vita …………………………………………………….…………………………….…...x Abstract of the Dissertation ………………………………………………….……….….xi INTRODUCTION.……………………………………………………………….……....1 CHAPTER ONE. Queering Chineseness and Kinship: Strategies of Rewriting by Chen Ran, Chen Xue and Huang Biyun………………………….………...33 -

The Visible and Invisible Worlds of Tsai Ming-Liang's Goodbye, Dragon Inn

Screening Today: The Visible and Invisible Worlds of Tsai Ming-liang's Goodbye, Dragon Inn Elizabeth Wijaya Discourse, Volume 43, Number 1, Winter 2021, pp. 65-97 (Article) Published by Wayne State University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/790601 [ Access provided at 26 May 2021 21:04 GMT from University of Toronto Library ] Screening Today: The Visible and Invisible Worlds of Tsai Ming- liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn Elizabeth Wijaya Waste is the interface of life and death. It incarnates all that has been rendered invisible, peripheral, or expendable to history writ large, that is, history as the tale of great men, empire, and nation. —Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother (2006) A film operates through what it withdraws from the visible. —Alain Badiou, Handbook of Inaesthetics (2004) 1. Goodbye, Dragon Inn in the Time After Where does cinema begin and end? There is a series of images in Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003), directed by Tsai Ming-liang, that contain the central thesis of this essay (figure 1). In the first image of a canted wide shot, Chen Discourse, 43.1, Winter 2021, pp. 65–97. Copyright © 2021 Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309. ISSN 1522-5321. 66 Elizabeth Wijaya Figure 1. The Ticket Lady’s face intercepting the projected light in Good- bye, Dragon Inn (Homegreen Films, 2003). Shiang-Chyi’s character of the Ticket Lady is at the lower edge of the frame, and with one hand on the door of a cinema hall within Fuhe Grand Theater, she looks up at the film projection of a martial arts heroine in King Hu’s Dragon Inn (1967). -

REBELS of the NEON GOD (QUING SHAO NIAN NE ZHA) Dir

bigworldpictures.org presents Booking contact: Jonathan Howell Big World Pictures [email protected] Tel: 917-400-1437 New York and Los Angeles Press Contact: Sasha Berman Shotwell Media Tel: 310-450-5571 [email protected] NY THEATRICAL RELEASE: APRIL 10TH LA THEATRICAL RELEASE: JUNE 12TH SYNOPSIS REBELS OF THE NEON GOD (QUING SHAO NIAN NE ZHA) Dir. Tsai Ming-liang Taiwan / 1992/2014 / 106 min / DCP! In Mandarin, with English subtitles Aspect ratio: 1.85:1 Sound: Dual Mono Best First Film – Nantes Three Continents Film Festival Best Film – International Feature Film Competition – Torino Intl. Festival of Young Cinema Best Original Score – Golden Horse Film Festival Tsai Ming-liang emerged on the world cinema scene in 1992 with his groundbreaking first feature, REBELS OF THE NEON GOD. His debut already includes a handful of elements familiar to fans of subsequent work: a deceptively spare style often branded “minimalist”; actor Lee Kang-sheng as the silent and sullen Hsiao-kang; copious amounts of water, whether pouring from the sky or bubbling up from a clogged drain; and enough urban anomie to ensure that even the subtle humor in evidence is tinged with pathos. The loosely structured plot involves Hsiao-kang, a despondent cram school student, who becomes obsessed with young petty thief Ah-tze, after Ah-tze smashes the rearview mirror of a taxi driven by Hsiao-kang’s father. Hsiao-kang stalks Ah-tze and his buddy Ah-ping as they hang out in the film’s iconic arcade (featuring a telling poster of James Dean on the wall) and other locales around Taipei, and ultimately takes his revenge. -

Friday, April 10 6:30 T1 Days. 2020. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming

Tsai Ming-Liang: In Dialogue with Time, Memory, and Self April 10 - 26, 2020 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters Friday, April 10 6:30 T1 Days. 2020. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang 127min. Saturday, April 11 2:00 T2 Goodbye, Dragon Inn. 2003. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 82 min. 4:00 T1 (Lobby) Tsai Ming-Liang: Improvisations on the Memory of Cinema 6:30 T1 Vive L’Amour. 1994. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 118 min. Sunday, April 12 2:30 T2 Face. 2009. Taiwan/France. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 138 min. Monday, April 13 6:30 T1 No Form. 2012. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang 20 min. Followed by: Journey to the West. 2014. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 56 min. Tuesday, April 14 4:30 T1 Rebels of the Neon God. 1992. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 106 min. Wednesday, April 15 4:00 T2 The River. 1997. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 115 min. 6:30 T2 The Missing. 2003. Taiwan. Directed by Lee Kang-Sheng. 87 min. Preceded by: Single Belief. 2016. Taiwan. Directed by Lee Kang-Sheng. 15 min. Thursday, April 16 4:00 T2 I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone. 2006. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 115 min. 7:00 T2 What Times Is It There? 2001. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 116 min. Friday, April 17 4:00 T2 The Hole. 1998. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 93 min. 7:00 T1 Stray Dogs. 2013. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. -

The Iafor Journal of Media, Communication & Film

the iafor journal of media, communication & film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: James Rowlins ISSN: 2187-0667 The IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Editor: James Rowlins, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Associate Editor: Celia Lam, University of Notre Dame Australia, Australia Assistant Editor: Anna Krivoruchko, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Advisory Editor: Jecheol Park, National University of Singapore, Singapore Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-0667 Online: JOMCF.iafor.org Cover photograph: Harajuku, James Rowlins IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Edited by James Rowlins Table of Contents Notes on Contributors 1 Introduction 3 Editor, James Rowlins Interview with Martin Wood: A Filmmaker’s Journey into Research 5 Questions by James Rowlins Theorizing Subjectivity and Community Through Film 15 Jakub Morawski Sinophone Queerness and Female Auteurship in Zero Chou’s Drifting Flowers 22 Zoran Lee Pecic On Using Machinima as “Found” in Animation Production 36 Jifeng Huang A Story in the Making: Storytelling in the Digital Marketing of 53 Independent Films Nico Meissner Film Festivals and Cinematic Events Bridging the Gap between the Individual 63 and the Community: Cinema and Social Function in Conflict Resolution Elisa Costa Villaverde Semiotic Approach to Media Language 77 Michael Ejstrup and Bjarne le Fevre Jakobsen Revitalising Indigenous Resistance and Dissent through Online Media 90 Elizabeth Burrows IAFOR Journal of Media, Communicaion & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributors Dr. -

What Time Is It There?

What Time Is It There? 404110603 Charlie Lee 404110093 Daniel Hsu 404110586 Dean Lee 405110466 Leo Bao 404110615 Rex Huang 404110471 Tim Liu 4. Dean -- different aspects of time -- characters in different time zones kang -- *constrained in his inner self and his time --connects with Chyi and then to Paris Mother -- connects via her religious belief (talking to the fish, watering the plant) -- *confines herself in her own imaginary world. Chyi -- Kang's "way out." -- * wrist watch: two time zones -- three time zones -- in the theatre *Also the railroad scenes 3 sex scenes -- good quote from Ebert to explain them. Chyi -- "experiment with the other woman? Rex -- Time, Space and Human Flows; You also discuss the possibility of Chyi being Kang's fantasy Multiple Time --> Human flows -- 1) Chyi crossing national boundaries; 2) daily encounters --Can time be changed? * He changes it first at home and then different spaces of flows and thus connects with human flows. What does he long for? --> They want to break through their present constraints. time-space convergence -- at the railroad scene --> no friction? Is Chyi part of Kang's fantasy of Paris? Also the Father at the end? Leo-- Symbols -- the meanings you discuss are all possible in this "minimalist" film.--You are producing stories out of it. -- Circle, watch, clock -- to change the clock. a romantic act to be in the same time zone with Chyi -- This is a 2001 film, so maybe mobile phone is not that prevalent. -- water --also a means of connection, besides being a means of survival -- plant --the three family members are connected through the plant. -

Aspects of Chinese Cinema Today

Aspects of Chinese Cinema Today By Toh, Hai Leong Spring 1997 Issue of KINEMA 1. THE TAIWANESE ANTONIONI: TSAI MING-LIANG’S DISPLACEMENT OF LOVE IN AN URBAN ENVIRONMENT NO, Tsai Ming-liang is not in fact Taiwanese. The bespectacled 40-year-old bachelor was born in Kuching, Sarawak (East Malaysia) and only came to Taiwan for a college education. After graduating with a degree in drama and film in Taiwan’s University, he settled there and impressed critics with several experimental plays and television movies such as Give Me A Home (1988), The Happy Weaver(1989), My Name is Mary (1990), Ah Hsiung’s First Love(1990). He made a brilliant film debut in 1992 with Rebels Of The Neon God and his film Vive l’amour shared Venice’s Golden Lion for Best Film with Milcho Manchevski’s Before The Rain (1994). Rebels of the Neon God, a film about aimless and nihilistic Taipei youths, won numerous awards abroad: Among them, the Best Film award at the Festival International Cinema Giovani (1993), Best Film of New Director Award of Torino Film Festival (1993), the Best Music Award, Grand Prize and Best Director Awards of Taiwan Golden Horse Festival (1992), the Best Film of Chinese Film Festival (1992), a bronze award at the Tokyo International Film Festival in 1993 and the Best Director Award and Leading Actor Award at the Nantes Festival des Trois Continents in 1994.(1) For the sake of simplicity, he will be referred to as ”Taiwanese”, since he has made Taipei, (Taiwan) his home. In fact, he is considered to be among the second generation of New Wave filmmakers in Taiwan. -

Realism O Fantasm Agórico

FANTASMAGÓRICO REALISMO FANTASMAGÓRICO REALISMO UNIVERSIDADE CINUSP PAULO EMÍLIO DE SÃO PAULO DiretorA REITOR Patrícia Moran Fernandes Marco Antonio Zago VICE-DiretorA VICE-Reitor Esther Império Hamburger Vahan Agopyan COORDENADOR DE proDUÇÃO PRó-Reitor DE GRADUAÇÃO Thiago Afonso de André Antonio Carlos Hernandes ESTAGIÁRIOS DE proDUÇÃO PRó-Reitor DE Pós-GRADUAÇÃO Afonso Moretti Bernadete Dora Gombossy Ayume Oliveira de Melo Franco Cauê Teles PRó-Reitor DE PESQUISA Cédric Fanti José Eduardo Krieger Gabrielle Criss Lorena Duarte PRÓ-REITORIA DE CULTURA Nayara Xavier E EXTENSÃO UNIVERSITÁRIA Pedro Nishiyama Thiago Oliveira PRó-ReitorA DE CULTURA Rodrigo Neves E EXTENSÃO UNIVERSITÁRIA ProgrAMAÇÃO VISUAL Maria Arminda do Nascimento Arruda Thiago Quadros PRó-Reitor ADJUNto DE EXTENSÃO ProJECIONISTA Moacyr Ayres Novaes Filho Fransueldes de Abreu PRó-Reitor ADJUNto DE CULTURA ASSISTENTE TÉCNICO DE DIREÇÃO João Marcos de Almeida Lopes Maria José Ipólito ASSESSOR TÉCNICO DE GABINETE AUXILIAR ADMINISTRATIVA José Nicolau Gregorin Filho Maria Aparecida Santos Rubens Beçak ANALISTA ADMINISTRATIVA Telma Bertoni REALISMO FANTASMAGÓRICO COLEÇÃO CINUSP – VOLUME 7 COORDENAÇÃO GERAL DESIGN GRÁFICO Patrícia Moran e Esther Hamburger Thiago Quadros ORGANIZAÇÃO ILUSTRAÇÃO DA CAPA Cecília Mello Heitor Isoda PRODUÇÃO FOTO PARA CAPA Lorena Duarte Wilson Rodrigues Cédric Fanti Pedro Nishiyama Thiago Almeida Thiago de André Mello, Cecília (org.) Realismo Fantasmagórico / Cecília Mello et al São Paulo: Pró-Reitoria de Cultura e Extensão Universitária - USP, 2015 320 p.; 21 x 15,5 cm ISBN 978-85-62587-21-4 1. Cinema 2. Realismo 3. Leste Asiático I. Mello, Cecília (org.) II. Elsaesser, Thomas III. De Luca, Tiago IV. Vieira Jr., Erly V. Andrew, Dudley VI. Weerasethakul, Apichatpong VII. Ma, Jean VIII. -

The Care for Opacity – on Tsai Ming-Liang's Conservative Filmic

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Erik Bordeleau The care for opacity – On Tsai Ming-Liang’s conservative filmic gesture 2012 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15052 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bordeleau, Erik: The care for opacity – On Tsai Ming-Liang’s conservative filmic gesture. In: NECSUS. European Journal of Media Studies, Jg. 1 (2012), Nr. 2, S. 115–131. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15052. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.5117/NECSUS2012.2.BORD Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org NECSUS Published by: Amsterdam University Press The care for opacity On Tsai Ming-Liang’s conservative filmic gesture Erik Bordeleau NECSUS 1 (2):115–131 DOI: 10.5117/NECSUS2012.2.BORD Keywords: film, gesture, opacity, Tsai Ming-Liang A thin veneer of immediate reality is spread over natural and artificial matter, and whoever wishes to remain in the now, with the now, on the now, should please not break its tension film. – Vladimir Nabokov, Transparent Things Transparent things The opening generic of Tsai Ming-Liang’s Face (2009) has just ended. In the background, we hear the hum of a café. -

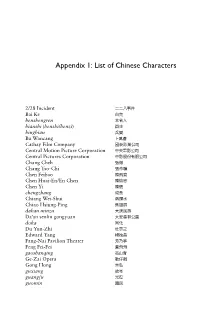

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters 2/28 Incident 二二八事件 Bai Ke 白克 benshengren 本省人 bianshi (benshi/benzi) 辯士 bingbian 兵變 Bu Wancang 卜萬蒼 Cathay Film Company 國泰影業公司 Central Motion Picture Corporation 中央電影公司 Central Pictures Corporation 中影股份有限公司 Chang Cheh 張徹 Chang Tso-Chi 張作驥 Chen Feibao 陳飛寶 Chen Huai-En/En Chen 陳懷恩 Chen Yi 陳儀 chengzhang 成長 Chiang Wei- Shui 蔣謂水 Chiao Hsiung- Ping 焦雄屏 dahan minzu 大漢民族 Da’an senlin gongyuan 大安森林公園 doka 同化 Du Yun- Zhi 杜雲之 Edward Yang 楊德昌 Fang- Nai Pavilion Theater 芳乃亭 Feng Fei- Fei 鳳飛飛 gaoshanqing 高山青 Ge- Zai Opera 歌仔戲 Gong Hong 龔弘 guxiang 故鄉 guangfu 光復 guomin 國民 188 Appendix 1 guopian 國片 He Fei- Guang 何非光 Hou Hsiao- Hsien 侯孝賢 Hu Die 胡蝶 Huang Shi- De 黃時得 Ichikawa Sai 市川彩 jiankang xieshi zhuyi 健康寫實主義 Jinmen 金門 jinru shandi qingyong guoyu 進入山地請用國語 juancun 眷村 keban yingxiang 刻板印象 Kenny Bee 鍾鎮濤 Ke Yi-Zheng 柯一正 kominka 皇民化 Koxinga 國姓爺 Lee Chia 李嘉 Lee Daw- Ming 李道明 Lee Hsing 李行 Li You-Xin 李幼新 Li Xianlan 李香蘭 Liang Zhe- Fu 梁哲夫 Liao Huang 廖煌 Lin Hsien- Tang 林獻堂 Liu Ming- Chuan 劉銘傳 Liu Na’ou 劉吶鷗 Liu Sen- Yao 劉森堯 Liu Xi- Yang 劉喜陽 Lu Su- Shang 呂訴上 Ma- zu 馬祖 Mao Xin- Shao/Mao Wang- Ye 毛信孝/毛王爺 Matuura Shozo 松浦章三 Mei- Tai Troupe 美臺團 Misawa Mamie 三澤真美惠 Niu Chen- Ze 鈕承澤 nuhua 奴化 nuli 奴隸 Oshima Inoshi 大島豬市 piaoyou qunzu 漂游族群 Qiong Yao 瓊瑤 qiuzhi yu 求知慾 quanguo gejie 全國各界 Appendix 1 189 renmin jiyi 人民記憶 Ruan Lingyu 阮玲玉 sanhai 三害 shandi 山地 Shao 邵族 Shigehiko Hasumi 蓮實重彦 Shihmen Reservoir 石門水庫 shumin 庶民 Sino- Japanese Amity 日華親善 Society for Chinese Cinema Studies 中國電影史料研究會 Sun Moon Lake 日月潭 Taiwan Agricultural Education Studios -

The Many Faces of Tsai Ming-Liang: Cinephilia, the French Connection, and Cinema in the Gallery

IJAPS, Vol. 13, No. 2, 141–160, 2017 THE MANY FACES OF TSAI MING-LIANG: CINEPHILIA, THE FRENCH CONNECTION, AND CINEMA IN THE GALLERY Beth Tsai * Department of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, United States email: [email protected] Published online: 15 July 2017 To cite this article: Tsai, B. 2017. The many faces of Tsai Ming-liang: Cinephilia, the French connection, and cinema in the gallery. International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies 13 (2): 141–160, https://doi.org/10.21315/ijaps2017.13.2.7 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.21315/ijaps2017.13.2.7 ABSTRACT The Malaysia-born, Taiwan-based filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang's Visage (2009) is a film that was commissioned by the Louvre as part of its collection. His move to the museum space raises a number of questions: What are some of the implications of his shift in practice? What does it mean to have a film, situated in art galleries or museum space, invites us to think about the notion of cinema, spatial configuration, transnational co-production and consumption? To give these questions more specificity, this article willlook at the triangular relationship between the filmmaker's prior theatre experience, French cinephilia's influence, and cinema in the gallery, using It's a Dream (2007) and Visage as two case studies. I argue Tsai's film and video installation need to be situated in the intersection between the moving images and the alternative viewing experiences, and between the global and regional film cultures taking place at the theatre-within-a-gallery site. -

China Cat and Dog We

(May - June 2013) NGOs agree to work together to end “criminal and cruel” dog and cat eating in China Jill Robinson, Founder and CEO of Animals Asia Foundation presents at the symposium Group photo for the 4th China Companion Animal Symposium. Animal welfare organisations across China have Survey data presented to delegates at Changsha, agreed to work together against the “criminal and collected from across 28 provinces, showed that cruel” dog and cat meat industry. the dog meat industry continues to rely on animals stolen from homes and on strays picked up from the Over 170 delegates were in attendance at the streets. Many such dogs are poisoned before being 4th China Companion Animal Symposium in taken to markets and restaurants and are served Changsha, Hunan Province hosted by Animals Asia with toxic residues still present. Foundation and co-organised by Humane Society International (HSI) and Changsha Small Animal Delegates shared evidence that criminality extends Protection Association. They represented around to every level of the dog meat trade from theft, 100 NGOs, including both grassroots Chinese through to transportation and sale. The shared organisations and international charities. findings will be published later this year. 1 Bimonthly Review Cat and Dog Welfare Programme, China Conference attendees agreed a final resolution with the government to highlight and crack down on to work together across China towards common the inherent illegalities of the trade. goals, specifically aiming to reduce demand through increased public awareness of the cruelty and health More details of the symposium: risks associated with dog and cat meat and working http://www.animalsasia.org/index.php?UID=2KYBB4XEHO8 “Be healthy.