The Visible and Invisible Worlds of Tsai Ming-Liang's Goodbye, Dragon Inn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: the Politics of Reading Between East and East a Dissertati

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: The Politics of Reading Between East and East A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Alvin Ka Hin Wong Committee in Charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Lowe, Co-Chair Professor Patrick Anderson Professor Rosemary Marangoly George Professor Larissa N. Heinrich 2012 Copyright Alvin Ka Hin Wong, 2012 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Alvin Ka Hin Wong is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page …………………………………………………….……………….….…iii Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………..…….…iv List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………….…........v Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………….....vi Vita …………………………………………………….…………………………….…...x Abstract of the Dissertation ………………………………………………….……….….xi INTRODUCTION.……………………………………………………………….……....1 CHAPTER ONE. Queering Chineseness and Kinship: Strategies of Rewriting by Chen Ran, Chen Xue and Huang Biyun………………………….………...33 -

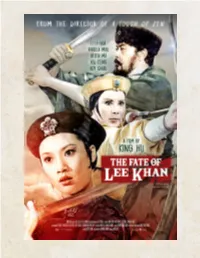

The-Fate-Of-Lee-Khan Presskit.Pdf

presents NEW 2K DIGITAL RESTORATION Hong Kong & Taiwan / 1973 / Action / Mandarin with English Subtitles 106 minutes / 2.35:1 / 5.1 Surround Sound U.S. THEATRICAL PREMIERE Opening April 5th in New York at Metrograph Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Michael Lieberman | Metrograph | (212) 660-0312 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (201) 736-0261 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS In his follow-up to the critically acclaimed A TOUCH OF ZEN, trailblazing filmmaker King Hu brings together an all-star female cast, including Hong Kong cinema stalwart Li Li-hua and Angela “Lady Kung Fu” Mao, in this lively martial arts adventure. When Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army, resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. Featuring stunning action sequences choreographed by Jackie Chan’s “Kung Fu elder brother” Sammo Hung and a generous mix of intrigue and humor, THE FATE OF LEE KHAN is a legendary wuxia masterpiece. SHORT SYNOPSIS Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army. Resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. LOGLINE King Hu's legendary wuxia masterpiece, starring Li Li-hua, Angela Mao and Hsu Feng. SELECT PRESS “The Fate of Lee Khan is to the Chinese martial arts movie what Once Upon a Time in the West is to the Italian Western: a brilliant anthology of its genre's theme and styles, yielding an exhilaratingly original vision.” –Time Out “The Fate of Lee Khan is a masterclass in getting the maximum from every aspect of production. -

Realism O Fantasm Agórico

FANTASMAGÓRICO REALISMO FANTASMAGÓRICO REALISMO UNIVERSIDADE CINUSP PAULO EMÍLIO DE SÃO PAULO DiretorA REITOR Patrícia Moran Fernandes Marco Antonio Zago VICE-DiretorA VICE-Reitor Esther Império Hamburger Vahan Agopyan COORDENADOR DE proDUÇÃO PRó-Reitor DE GRADUAÇÃO Thiago Afonso de André Antonio Carlos Hernandes ESTAGIÁRIOS DE proDUÇÃO PRó-Reitor DE Pós-GRADUAÇÃO Afonso Moretti Bernadete Dora Gombossy Ayume Oliveira de Melo Franco Cauê Teles PRó-Reitor DE PESQUISA Cédric Fanti José Eduardo Krieger Gabrielle Criss Lorena Duarte PRÓ-REITORIA DE CULTURA Nayara Xavier E EXTENSÃO UNIVERSITÁRIA Pedro Nishiyama Thiago Oliveira PRó-ReitorA DE CULTURA Rodrigo Neves E EXTENSÃO UNIVERSITÁRIA ProgrAMAÇÃO VISUAL Maria Arminda do Nascimento Arruda Thiago Quadros PRó-Reitor ADJUNto DE EXTENSÃO ProJECIONISTA Moacyr Ayres Novaes Filho Fransueldes de Abreu PRó-Reitor ADJUNto DE CULTURA ASSISTENTE TÉCNICO DE DIREÇÃO João Marcos de Almeida Lopes Maria José Ipólito ASSESSOR TÉCNICO DE GABINETE AUXILIAR ADMINISTRATIVA José Nicolau Gregorin Filho Maria Aparecida Santos Rubens Beçak ANALISTA ADMINISTRATIVA Telma Bertoni REALISMO FANTASMAGÓRICO COLEÇÃO CINUSP – VOLUME 7 COORDENAÇÃO GERAL DESIGN GRÁFICO Patrícia Moran e Esther Hamburger Thiago Quadros ORGANIZAÇÃO ILUSTRAÇÃO DA CAPA Cecília Mello Heitor Isoda PRODUÇÃO FOTO PARA CAPA Lorena Duarte Wilson Rodrigues Cédric Fanti Pedro Nishiyama Thiago Almeida Thiago de André Mello, Cecília (org.) Realismo Fantasmagórico / Cecília Mello et al São Paulo: Pró-Reitoria de Cultura e Extensão Universitária - USP, 2015 320 p.; 21 x 15,5 cm ISBN 978-85-62587-21-4 1. Cinema 2. Realismo 3. Leste Asiático I. Mello, Cecília (org.) II. Elsaesser, Thomas III. De Luca, Tiago IV. Vieira Jr., Erly V. Andrew, Dudley VI. Weerasethakul, Apichatpong VII. Ma, Jean VIII. -

Legend of the Mountain

LEGEND OF THE MOUNTAIN A film by King Hu 1979 / Taiwan and Hong Kong / 184 min. / In Mandarin with English subtitles Press materials: www.kinolorber.com Distributor Contact: Kino Lorber 333 W. 39th Street New York, NY 10018 (212) 629-6880 Jonathan Hertzberg, [email protected] Publicity Contacts: Rodrigo Brandao, [email protected] Michael Lieberman, [email protected] 1 Synopsis A travelling scholar, intent on translating a Buddhist sutra, loses his way in the mountains. Time and space collapse around him as he continues his journey, encountering ghostly visitations amid a haunting fantasia of color, light and landscape. King Hu rose to prominence in the 1960s and 70s as a superb director of wuxia, a subgenre of samurai film dealing with swords, sorcery and chivalrous heroes. Legend of the Mountain comes from the director’s later period, when his artistry, specifically his landscape compositions, was at the height of its powers. The film’s astonishing nature shots, shot on location in the Korean countryside, are reminiscent of Terrence Malick, while the reflective blend of myth and history is all Hu’s own. 2 About the Restoration The complete version of Legend of the Mountain has been restored in 4K from a first generation, vintage inter-positive and from the sound negative preserved at the Taiwan Film Institute. The original camera negative, re-edited into a shorter theatrical version, was not assessed as the best source because it was completely damaged by mold, and the coiled film strips of some reels were sticky and glued together due to the decay of the support film base. -

Alternative Titles Index

VHD Index - 02 9/29/04 4:43 PM Page 715 Alternative Titles Index While it's true that we couldn't include every Asian cult flick in this slim little vol- ume—heck, there's dozens being dug out of vaults and slapped onto video as you read this—the one you're looking for just might be in here under a title you didn't know about. Most of these films have been released under more than one title, and while we've done our best to use the one that's most likely to be familiar, that doesn't guarantee you aren't trying to find Crippled Avengers and don't know we've got it as The Return of the 5 Deadly Venoms. And so, we've gathered as many alternative titles as we can find, including their original language title(s), and arranged them in alphabetical order in this index to help you out. Remember, English language articles ("a", "an", "the") are ignored in the sort, but foreign articles are NOT ignored. Hey, my Japanese is a little rusty, and some languages just don't have articles. A Fei Zheng Chuan Aau Chin Adventure of Gargan- Ai Shang Wo Ba An Zhan See Days of Being Wild See Running out of tuas See Gimme Gimme See Running out of (1990) Time (1999) See War of the Gargan- (2001) Time (1999) tuas (1966) A Foo Aau Chin 2 Ai Yu Cheng An Zhan 2 See A Fighter’s Blues See Running out of Adventure of Shaolin See A War Named See Running out of (2000) Time 2 (2001) See Five Elements of Desire (2000) Time 2 (2001) Kung Fu (1978) A Gai Waak Ang Kwong Ang Aau Dut Air Battle of the Big See Project A (1983) Kwong Ying Ji Dut See The Longest Nite The Adventures of Cha- Monsters: Gamera vs. -

Press Release Austin Asian American Film Festival Announces “Prismatic Taiwan” a Queer Film Series

Press Release Taiwanese American artist I-Ping Chiang was inspired by the Southern Taiwanese city of Kaohsiung’s “Love River” or Ai He (愛河), a symbol of great cultural and economic significance in Taiwan. Austin Asian American Film Festival Announces “Prismatic Taiwan” A Queer Film Series Co-presented by Taiwan Academy Houston, OFTaiwan, and Taiwanese American Citizens League; Sponsored by the Taiwan Ministry of Culture AUSTIN, TX – The Austin Asian American Film Festival (AAAFF) is thrilled to co-present a virtual, six-film series celebrating the past and present of queer Taiwanese cinema. The viewing period for all films--including exclusive filmmaker Q&As--will be September 4-13, 2020. Access to the films will be available on the festival’s newly re-designed website, aaafilmfest.org. The legalization of same-sex marriage in Taiwan (which took effect in May 2019) inspired the AAAFF team to examine the evolution of LGBTQ subjects throughout the country’s cinematic history. The resulting lineup of films (many of which were never released or remain elusive in the United States) spans 1970 to 2016, and includes such key filmmaking figures in Taiwanese cinema as Tsai Ming-liang, Mickey Chen, and Zero Chou. The series slate serves as a documentation of history as it unfolds, containing contemporaneous portrayals of queer subcultures across various eras--from the gay club scene in the early 1980s (Yu Kan-ping’s OUTCASTS) to the online culture of the early 21st century (Zero Chou’s SPIDER LILIES). Taken as a whole, these films give viewers a firsthand look at the decades-long fight for acceptance waged by Taiwanese people across the LGBTQ spectrum--as subtextual portrayals of hidden desire (as in Mou Tun-fei’s THE END OF THE TRACK) give way to direct confrontations with society (Mickey Chen and Mia Chen’s NOT SIMPLY A WEDDING BANQUET) and family (Huang Hui-chen’s SMALL TALK). -

Download a Touch of Zen Press Kit (PDF)

presents In director King Hu’s grandest work, the noblewoman Yang (Hsu Feng), a fugitive hiding in a small village, must escape into the wilderness with a shy scholar and two aides. There, the quartet face a massive group of fighters, and are joined by a band of Buddhist monks who are surprisingly skilled in the art of battle. Janus Films is proud to present the original, uncut version of this classic in a sparkling new 4K restoration. “ The visual style will set your eyes on fire.” —Time Out London “ Truly spectacular.” —A. H. Weiler, The New York Times © 1971 Union Film Co., Ltd. / © 2015 Taiwan Film Institute. All rights reserved. janusfilms.com/hu “ An amazing and unique director.” —Ang Lee Taiwan • 1971 • 180 minutes • Color • Monaural In Mandarin with English subtitles • 2.35:1 aspect ratio Screening format: 4K DCP CREDITS Director/Scriptwriter: King Hu Starring: Producers: Sha Jung-feng, Hsu Feng as Yang Huizhen Hsia-wu Liang Fang Shi Jun as Gu Shengzhai Cinematographer: Hua Huiying Bai Ying as General Shih Editors: King Hu, Wen-chaio Wang Chin-chen Music: Wu Dajiang Martial arts choreographers: Han Yingjie, Pan Yao-kun Booking Inquiries: Janus Films Press Contact: Ryan Werner [email protected] • 212-756-8761 [email protected] • 917-254-7653 WUXIA: A PRIMER Although in the West most often applied to film, the term wuxia—literally “martial [wu] hero [xia]”—in fact refers to a genre of Chinese fiction that is represented in every medium, from literature to opera to, of course, movies. Dating back to 300 BCE in its protean form, the wuxia narrative traditionally follows a hero from the lower class without official affiliation who pursues righteousness and/or revenge while adhering to a code of chivalrous behavior. -

Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary Stephen Edward Spence University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 4-17-2017 "Revealing Reality": Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary Stephen Edward Spence University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Spence, Stephen Edward. ""Revealing Reality": Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/54 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stephen Edward Spence Candidate American Studies Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Rebecca Schreiber, Chairperson Alyosha Goldstein Susan Dever Luisela Alvaray ii "REVEALING REALITY": FOUR ASIAN FILMMAKERS VISUALIZE THE TRANSNATIONAL IMAGINARY by STEPHEN EDWARD SPENCE B.A., English, University of New Mexico, 1995 M.A., Comparative Literature & Cultural Studies, University of New Mexico, 2002 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2017 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project has been long in the making, and therefore requires substantial acknowledgments of gratitude and recognition. First, I would like to thank my fellow students in the American Studies Graduate cohort of 2003 (and several years following) who always offered support and friendship in the earliest years of this project. -

Tsai Ming-Liang, One of Contemporary Cinema's

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TSAI MING-LIANG, ONE OF CONTEMPORARY CINEMA’S MOST CELEBRATED DIRECTORS, TO RECEIVE A MAJOR RETROSPECTIVE April 10–26, 2015 Astoria, New York, February 26, 2015—Tsai Ming-liang, the defining artist of Taiwan’s Second Wave of filmmakers, will be the subject of a major retrospective at Museum of the Moving Image, from April 10 through 26, 2015—the most comprehensive presentation of Tsai’s work ever presented in New York. Distinguished by a unique austerity of style and a minutely controlled mise-en-scene in which the smallest gestures give off enormous reverberations, Tsai’s films comprise one of the most monumental bodies of work of the past 25 years. And, with actor Lee Kang-sheng, who has appeared in every film, Tsai’s stories express an intimate acquaintance with despair and isolation, punctuated by deadpan humor. The Museum’s eighteen-film retrospective, Tsai Ming-liang, includes all of the director’s feature films as well as many rare shorts, an early television feature (Boys, 1991), and the revealing 2013 documentary Past Present, by Malaysian filmmaker Tiong Guan Saw. From Rebels of the Neon God (1992), which propelled Tsai into the international spotlight, and his 1990s powerhouse films Vive L’Amour (1994), The River (1997), and The Hole (1998); and films made in his native Malaysia, I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone (2006) and Sleeping on Dark Waters (2008); to his films made in France, What Time Is It There? (2001), Face (Visage) (2009), and Journey to the West (2014); the retrospective captures Tsai’s changing aesthetic: his gradual (but not continual) renouncement of classical cinematic techniques, an evolution that is also underscored by the shift from celluloid to digital. -

Goodbye, Dragon Inn and the “Death of Cinema”

arts Article On Dissipation: Goodbye, Dragon Inn and the “Death of Cinema” Anders Bergstrom Department of Communication Arts, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada; [email protected] Received: 29 September 2018; Accepted: 23 November 2018; Published: 27 November 2018 Abstract: This paper explores the cinematic meta-theme of the “death of cinema” through the lens of Taiwanese director, Tsai Ming-liang’s 2003 film, Goodbye, Dragon Inn. In the film, the final screening of the wuxia pian classic, Dragon Inn, directed by King Hu, provides a focal point for the exploration of the diminished experience of institutional cinema in the post-cinematic age. Using the concept of “dissipation” in conjunction with a reappraisal of the turn to affect theory, this paper explores the kinds of subjective experiences that cinema can offer, and the affective experience of cinema-going itself, as portrayed in Goodbye, Dragon Inn. More specifically, in theorizing the role of dissipation in cinema-going, this paper explores the deployment of time and space in Goodbye, Dragon Inn and how it directs attention to the bodily action of cinema-going itself. The result is a critique of the possibilities of post-cinematic affects, rooted in an understanding of the way that late-capitalism continues to dominate and shape the range of experiences in the contemporary moment. Keywords: affect; post-cinema; subjectivity; temporality; perception; embodiment 1. Introduction: The “Death of Cinema” and the Post-Cinematic The transnational art cinema (a term favored by film scholars for the set of heterogenous film practices that emerged around the world after the Second World War) has frequently taken cinema 1 itself as a self-reflexive subject of reflection, as for example, in Fellini’s 8 2 (1963) or Godard’s Contempt (1963). -

Representations of Chinese Women Warriors in the Western Media

REPRESENTATIONS OF CHINESE WOMEN WARRIORS IN THE CINEMAS OF HONG KONG, MAINLAND CHINA AND TAIWAN SINCE 1980 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Chinese at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2007 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................. i ABSTRACT .................................................................................................... ii Introduction................................................................................................ 1 1. HERstory of Chinese women warriors ........................................... 13 1.1 Basic Imagery ...................................................................................... 13 1.2 Thematic Continuity.......................................................................... 17 1.3 A Brief History of Women Warriors in Chinese Cinemas....... .23 2. Western Influence .................................................................................. 43 2.1 Western Women Warriors ..............................................................44 2.2 Chinese Women Warriors in Hollywood ................................... 54 3. Hong Kong .................................................................................................61 3.1 Peking Opera Blue .................................................................................... 61 3.2 Dragon Inn ............................................................................................. -

Vertical Facility List

Facility List The Walt Disney Company is committed to fostering safe, inclusive and respectful workplaces wherever Disney-branded products are manufactured. Numerous measures in support of this commitment are in place, including increased transparency. To that end, we have published this list of the roughly 7,600 facilities in over 70 countries that manufacture Disney-branded products sold, distributed or used in our own retail businesses such as The Disney Stores and Theme Parks, as well as those used in our internal operations. Our goal in releasing this information is to foster collaboration with industry peers, governments, non- governmental organizations and others interested in improving working conditions. Under our International Labor Standards (ILS) Program, facilities that manufacture products or components incorporating Disney intellectual properties must be declared to Disney and receive prior authorization to manufacture. The list below includes the names and addresses of facilities disclosed to us by vendors under the requirements of Disney’s ILS Program for our vertical business, which includes our own retail businesses and internal operations. The list does not include the facilities used only by licensees of The Walt Disney Company or its affiliates that source, manufacture and sell consumer products by and through independent entities. Disney’s vertical business comprises a wide range of product categories including apparel, toys, electronics, food, home goods, personal care, books and others. As a result, the number of facilities involved in the production of Disney-branded products may be larger than for companies that operate in only one or a limited number of product categories. In addition, because we require vendors to disclose any facility where Disney intellectual property is present as part of the manufacturing process, the list includes facilities that may extend beyond finished goods manufacturers or final assembly locations.