Download Original 631.47 KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

REBELS of the NEON GOD (QUING SHAO NIAN NE ZHA) Dir

bigworldpictures.org presents Booking contact: Jonathan Howell Big World Pictures [email protected] Tel: 917-400-1437 New York and Los Angeles Press Contact: Sasha Berman Shotwell Media Tel: 310-450-5571 [email protected] NY THEATRICAL RELEASE: APRIL 10TH LA THEATRICAL RELEASE: JUNE 12TH SYNOPSIS REBELS OF THE NEON GOD (QUING SHAO NIAN NE ZHA) Dir. Tsai Ming-liang Taiwan / 1992/2014 / 106 min / DCP! In Mandarin, with English subtitles Aspect ratio: 1.85:1 Sound: Dual Mono Best First Film – Nantes Three Continents Film Festival Best Film – International Feature Film Competition – Torino Intl. Festival of Young Cinema Best Original Score – Golden Horse Film Festival Tsai Ming-liang emerged on the world cinema scene in 1992 with his groundbreaking first feature, REBELS OF THE NEON GOD. His debut already includes a handful of elements familiar to fans of subsequent work: a deceptively spare style often branded “minimalist”; actor Lee Kang-sheng as the silent and sullen Hsiao-kang; copious amounts of water, whether pouring from the sky or bubbling up from a clogged drain; and enough urban anomie to ensure that even the subtle humor in evidence is tinged with pathos. The loosely structured plot involves Hsiao-kang, a despondent cram school student, who becomes obsessed with young petty thief Ah-tze, after Ah-tze smashes the rearview mirror of a taxi driven by Hsiao-kang’s father. Hsiao-kang stalks Ah-tze and his buddy Ah-ping as they hang out in the film’s iconic arcade (featuring a telling poster of James Dean on the wall) and other locales around Taipei, and ultimately takes his revenge. -

Friday, April 10 6:30 T1 Days. 2020. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming

Tsai Ming-Liang: In Dialogue with Time, Memory, and Self April 10 - 26, 2020 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters Friday, April 10 6:30 T1 Days. 2020. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang 127min. Saturday, April 11 2:00 T2 Goodbye, Dragon Inn. 2003. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 82 min. 4:00 T1 (Lobby) Tsai Ming-Liang: Improvisations on the Memory of Cinema 6:30 T1 Vive L’Amour. 1994. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 118 min. Sunday, April 12 2:30 T2 Face. 2009. Taiwan/France. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 138 min. Monday, April 13 6:30 T1 No Form. 2012. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang 20 min. Followed by: Journey to the West. 2014. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 56 min. Tuesday, April 14 4:30 T1 Rebels of the Neon God. 1992. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 106 min. Wednesday, April 15 4:00 T2 The River. 1997. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 115 min. 6:30 T2 The Missing. 2003. Taiwan. Directed by Lee Kang-Sheng. 87 min. Preceded by: Single Belief. 2016. Taiwan. Directed by Lee Kang-Sheng. 15 min. Thursday, April 16 4:00 T2 I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone. 2006. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 115 min. 7:00 T2 What Times Is It There? 2001. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 116 min. Friday, April 17 4:00 T2 The Hole. 1998. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. 93 min. 7:00 T1 Stray Dogs. 2013. Taiwan. Directed by Tsai Ming-Liang. -

The Iafor Journal of Media, Communication & Film

the iafor journal of media, communication & film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: James Rowlins ISSN: 2187-0667 The IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Editor: James Rowlins, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Associate Editor: Celia Lam, University of Notre Dame Australia, Australia Assistant Editor: Anna Krivoruchko, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Advisory Editor: Jecheol Park, National University of Singapore, Singapore Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-0667 Online: JOMCF.iafor.org Cover photograph: Harajuku, James Rowlins IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Edited by James Rowlins Table of Contents Notes on Contributors 1 Introduction 3 Editor, James Rowlins Interview with Martin Wood: A Filmmaker’s Journey into Research 5 Questions by James Rowlins Theorizing Subjectivity and Community Through Film 15 Jakub Morawski Sinophone Queerness and Female Auteurship in Zero Chou’s Drifting Flowers 22 Zoran Lee Pecic On Using Machinima as “Found” in Animation Production 36 Jifeng Huang A Story in the Making: Storytelling in the Digital Marketing of 53 Independent Films Nico Meissner Film Festivals and Cinematic Events Bridging the Gap between the Individual 63 and the Community: Cinema and Social Function in Conflict Resolution Elisa Costa Villaverde Semiotic Approach to Media Language 77 Michael Ejstrup and Bjarne le Fevre Jakobsen Revitalising Indigenous Resistance and Dissent through Online Media 90 Elizabeth Burrows IAFOR Journal of Media, Communicaion & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributors Dr. -

Journal of Asian Studies Contemporary Chinese Cinema Special Edition

the iafor journal of asian studies Contemporary Chinese Cinema Special Edition Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: Seiko Yasumoto ISSN: 2187-6037 The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Editor: Seiko Yasumoto, University of Sydney, Australia Associate Editor: Jason Bainbridge, Swinburne University, Australia Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-6037 Online: joas.iafor.org Cover image: Flickr Creative Commons/Guy Gorek The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue I – Spring 2016 Edited by Seiko Yasumoto Table of Contents Notes on contributors 1 Welcome and Introduction 4 From Recording to Ritual: Weimar Villa and 24 City 10 Dr. Jinhee Choi Contested identities: exploring the cultural, historical and 25 political complexities of the ‘three Chinas’ Dr. Qiao Li & Prof. Ros Jennings Sounds, Swords and Forests: An Exploration into the Representations 41 of Music and Martial Arts in Contemporary Kung Fu Films Brent Keogh Sentimentalism in Under the Hawthorn Tree 53 Jing Meng Changes Manifest: Time, Memory, and a Changing Hong Kong 65 Emma Tipson The Taste of Ice Kacang: Xiaoqingxin Film as the Possible 74 Prospect of Taiwan Popular Cinema Panpan Yang Subtitling Chinese Humour: the English Version of A Woman, a 85 Gun and a Noodle Shop (2009) Yilei Yuan The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributers Dr. -

Aspects of Chinese Cinema Today

Aspects of Chinese Cinema Today By Toh, Hai Leong Spring 1997 Issue of KINEMA 1. THE TAIWANESE ANTONIONI: TSAI MING-LIANG’S DISPLACEMENT OF LOVE IN AN URBAN ENVIRONMENT NO, Tsai Ming-liang is not in fact Taiwanese. The bespectacled 40-year-old bachelor was born in Kuching, Sarawak (East Malaysia) and only came to Taiwan for a college education. After graduating with a degree in drama and film in Taiwan’s University, he settled there and impressed critics with several experimental plays and television movies such as Give Me A Home (1988), The Happy Weaver(1989), My Name is Mary (1990), Ah Hsiung’s First Love(1990). He made a brilliant film debut in 1992 with Rebels Of The Neon God and his film Vive l’amour shared Venice’s Golden Lion for Best Film with Milcho Manchevski’s Before The Rain (1994). Rebels of the Neon God, a film about aimless and nihilistic Taipei youths, won numerous awards abroad: Among them, the Best Film award at the Festival International Cinema Giovani (1993), Best Film of New Director Award of Torino Film Festival (1993), the Best Music Award, Grand Prize and Best Director Awards of Taiwan Golden Horse Festival (1992), the Best Film of Chinese Film Festival (1992), a bronze award at the Tokyo International Film Festival in 1993 and the Best Director Award and Leading Actor Award at the Nantes Festival des Trois Continents in 1994.(1) For the sake of simplicity, he will be referred to as ”Taiwanese”, since he has made Taipei, (Taiwan) his home. In fact, he is considered to be among the second generation of New Wave filmmakers in Taiwan. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 7, No. 1 (January 1993)

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 7· NUMBER 1 SPECIAL ISSUE ON CINEMA AND NATIONHOOD Baseball in the Post-American Cinema, or Life in the Minor Leagues I VIVIAN SOBCHACK A Nation T(w/o)o: Chinese Cinema(s) and Nationhood(s) CHRIS BERRY Gender, Ideology, Nation: Ju Dou in the Cultural Politics of China 52 w. A. CALLAHAN Cinema and Nation: Dilemmas of Representation in Thailand 81 ANNETTE HAMILTON Tibet: Projections and Perceptions 106 AISLINN SCOFIELD Warring Bodies: Most Nationalistic Selves 137 PATRICIA LEE MASTERS Book Reviews 149 JANUARY 1993 The East-West Center is a public, nonprofit education and research institution that examines such Asia-Pacific issues as the environment, economic development, population, international relations, resources, and culture and communication. Some two thousand research fellows, graduate students, educators, and professionals in business and government from Asia, the Pacific, and the United States annually work with the Center's staff in cooperative study, training, and research. The East-West Center was established in Hawaii in 1960 by the U.S. Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, private agencies, and corporations and through the East- West Center Foundation. The Center has an international board ofgovernors. Baseball in the Post-American Cinema, or Life in the Minor Leagues VIVIAN SOBCHACK The icons of our world are in trouble.! LEEIACOCCA AT THE beginning of Nation Into State: The Shifting Symbolic Founda tions of American -

Tiff Bell Lightbox Celebrates a Century of Chinese Cinema with Unprecedented Film Series, Exhibitions and Special Guests

May 6, 2013 .NEWS RELEASE. TIFF BELL LIGHTBOX CELEBRATES A CENTURY OF CHINESE CINEMA WITH UNPRECEDENTED FILM SERIES, EXHIBITIONS AND SPECIAL GUESTS - Programme features 80 films, free exhibitions and guests including Chen Kaige, Johnnie To and Jackie Chan - -Tickets on sale May 21 at 10 a.m. for TIFF Members, May 27 at 10 a.m. for non-members - Toronto – Noah Cowan, Artistic Director, TIFF Bell Lightbox, announced today details for a comprehensive exploration of Chinese film, art and culture. A Century of Chinese Cinema features a major film retrospective of over 80 titles, sessions with some of the biggest names in Chinese cinema, and a free exhibition featuring two internationally acclaimed visual artists. The flagship programme of the summer season, A Century of Chinese Cinema runs from June 5 to August 11, 2013. “A Century of Chinese Cinema exemplifies TIFF’s vision to foster new relationships and build bridges of cultural exchange,” said Piers Handling, Director and CEO of TIFF. “If we are, indeed, living in the Chinese Century, it is essential that we attempt to understand what that entails. There is no better way to do so than through film, which encourages cross-cultural understanding in our city and beyond.” “The history, legacy and trajectory of Chinese film has been underrepresented in the global cinematic story, and as a leader in creative and cultural discovery through film, TIFF Bell Lightbox is the perfect setting for A Century of Chinese Cinema,” said Noah Cowan, Artistic Director, TIFF Bell Lightbox. “With Chinese cinema in the international spotlight, an examination of the history and development of the region’s amazing artistic output is long overdue. -

Hollywood Abroad: Audiences and Cultural Exchange

Hollywood Abroad: Audiences and Cultural Exchange By Melvyn Stokes and Richard Maltby (eds.) London, British Film Institute 2004. ISBN: 1-84457-018-5 (hbk), 1-84457-051-7 (pbk). 164 pp. £16.99 (pbk), £50 (hbk) A review by Martin Barker, University of Wales, Aberystwyth This is the fourth in a line of excellent books to have come out of two conferences held in London, on Hollywood and its audiences. This fourth collection deals specifically with the reception of Hollywood films in some very different counties and cultural contexts. The quality and the verve of the essays in here (they are all, without exception, beautifully written) is testimony to the rise and the potentials of the new historical approaches to audiences (which has, I am pleased to see, sedimented into some on-going cross-cultural research projects on local film exhibition histories). I recommend this book, unreservedly. Its contributors demonstrate so well the potential for many kinds of archival research to extend our understanding of film reception. In here you will find essays on the reception of the phenomenon of Hollywood, and sometimes of specific films, in contexts as different as a mining town in Australia in the 1920s (Nancy Huggett and Kate Bowles), in and through an upmarket Japanese cinema in the aftermath of Japan's defeat in 1946 (Hiroshi Kitamura), in colonial Northern Rhodesia in the period leading up to independence (Charles Ambler), and in and around the rising nationalist movements in India in the 1920-30s (Priya Jaikumar). It is important, in understanding this book, that we pay attention to the specificities of these contexts. -

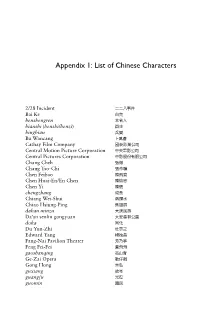

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters 2/28 Incident 二二八事件 Bai Ke 白克 benshengren 本省人 bianshi (benshi/benzi) 辯士 bingbian 兵變 Bu Wancang 卜萬蒼 Cathay Film Company 國泰影業公司 Central Motion Picture Corporation 中央電影公司 Central Pictures Corporation 中影股份有限公司 Chang Cheh 張徹 Chang Tso-Chi 張作驥 Chen Feibao 陳飛寶 Chen Huai-En/En Chen 陳懷恩 Chen Yi 陳儀 chengzhang 成長 Chiang Wei- Shui 蔣謂水 Chiao Hsiung- Ping 焦雄屏 dahan minzu 大漢民族 Da’an senlin gongyuan 大安森林公園 doka 同化 Du Yun- Zhi 杜雲之 Edward Yang 楊德昌 Fang- Nai Pavilion Theater 芳乃亭 Feng Fei- Fei 鳳飛飛 gaoshanqing 高山青 Ge- Zai Opera 歌仔戲 Gong Hong 龔弘 guxiang 故鄉 guangfu 光復 guomin 國民 188 Appendix 1 guopian 國片 He Fei- Guang 何非光 Hou Hsiao- Hsien 侯孝賢 Hu Die 胡蝶 Huang Shi- De 黃時得 Ichikawa Sai 市川彩 jiankang xieshi zhuyi 健康寫實主義 Jinmen 金門 jinru shandi qingyong guoyu 進入山地請用國語 juancun 眷村 keban yingxiang 刻板印象 Kenny Bee 鍾鎮濤 Ke Yi-Zheng 柯一正 kominka 皇民化 Koxinga 國姓爺 Lee Chia 李嘉 Lee Daw- Ming 李道明 Lee Hsing 李行 Li You-Xin 李幼新 Li Xianlan 李香蘭 Liang Zhe- Fu 梁哲夫 Liao Huang 廖煌 Lin Hsien- Tang 林獻堂 Liu Ming- Chuan 劉銘傳 Liu Na’ou 劉吶鷗 Liu Sen- Yao 劉森堯 Liu Xi- Yang 劉喜陽 Lu Su- Shang 呂訴上 Ma- zu 馬祖 Mao Xin- Shao/Mao Wang- Ye 毛信孝/毛王爺 Matuura Shozo 松浦章三 Mei- Tai Troupe 美臺團 Misawa Mamie 三澤真美惠 Niu Chen- Ze 鈕承澤 nuhua 奴化 nuli 奴隸 Oshima Inoshi 大島豬市 piaoyou qunzu 漂游族群 Qiong Yao 瓊瑤 qiuzhi yu 求知慾 quanguo gejie 全國各界 Appendix 1 189 renmin jiyi 人民記憶 Ruan Lingyu 阮玲玉 sanhai 三害 shandi 山地 Shao 邵族 Shigehiko Hasumi 蓮實重彦 Shihmen Reservoir 石門水庫 shumin 庶民 Sino- Japanese Amity 日華親善 Society for Chinese Cinema Studies 中國電影史料研究會 Sun Moon Lake 日月潭 Taiwan Agricultural Education Studios -

5 Taiwan's Cold War Geopolitics in Edward Yang's the Terrorizers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons 5 Taiwan’s Cold War Geopolitics in Edward Yang’s The Terrorizers Catherine Liu “I find myself in an awkward position,” Aijaz Ahmad confesses in his 1987 essay, “Jameson’s Rhetoric of Otherness.” He goes on to confess in a personal tone that he is troubled by the sense of betrayal he felt in reading his intellectual hero and comrade offer an anti-theoretical account of “Third World” literature and culture. Ahmad goes to great trouble to show that in his essay, “Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism,” that Jameson uses “Third World” and “oth- erness” in a polemically instrumental manner.1 Ahmad basically argues that “Third World literature” as Jameson describes it, does not exist. Ahmad’s critique of Jameson’s mystification of Third World literature (and by proxy cultural production) is at its most trenchant when he points out that Marxist theory should allow us to see the ways in which the world is unified by “a single mode of production, namely thecapitalist one” and that Jameson’s rejection of liberal ‘universalism’ in favor of the nationalist/postmodernist divide was specious at best.2 Ahmad insists on the particularity and diversity of South Asian literary culture in the face of Jameson’s naïve and sweeping claims about the culture produced by countries that have experienced imperialism, but I have never seen in English a thorough criticism of the way in which Fredric Jameson treated the work of the late Taiwanese filmmaker Edward Yang. -

The Many Faces of Tsai Ming-Liang: Cinephilia, the French Connection, and Cinema in the Gallery

IJAPS, Vol. 13, No. 2, 141–160, 2017 THE MANY FACES OF TSAI MING-LIANG: CINEPHILIA, THE FRENCH CONNECTION, AND CINEMA IN THE GALLERY Beth Tsai * Department of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, United States email: [email protected] Published online: 15 July 2017 To cite this article: Tsai, B. 2017. The many faces of Tsai Ming-liang: Cinephilia, the French connection, and cinema in the gallery. International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies 13 (2): 141–160, https://doi.org/10.21315/ijaps2017.13.2.7 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.21315/ijaps2017.13.2.7 ABSTRACT The Malaysia-born, Taiwan-based filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang's Visage (2009) is a film that was commissioned by the Louvre as part of its collection. His move to the museum space raises a number of questions: What are some of the implications of his shift in practice? What does it mean to have a film, situated in art galleries or museum space, invites us to think about the notion of cinema, spatial configuration, transnational co-production and consumption? To give these questions more specificity, this article willlook at the triangular relationship between the filmmaker's prior theatre experience, French cinephilia's influence, and cinema in the gallery, using It's a Dream (2007) and Visage as two case studies. I argue Tsai's film and video installation need to be situated in the intersection between the moving images and the alternative viewing experiences, and between the global and regional film cultures taking place at the theatre-within-a-gallery site.