Archaeological Reconstructions: an Experiential Approach to Archaeological and Historical Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CWLT Student Guide

Cold Weather Leader Training STUDENT GUIDE Northern Tier National High Adventure Boy Scouts of America Northern Tier National High Adventure Cold Weather Leader Training Student Guide Table of Contents About Okpik and CWLT ................................................................................................................ 4 How Do We Prepare Mentally and Physically? ............................................................................. 5 What are the risks? (Risk Advisory) ............................................................................................... 6 How do I prevent problems? ........................................................................................................... 7 General policies and information .................................................................................................... 7 How do I get there? ......................................................................................................................... 8 What do I need to pack?.................................................................................................................. 9 Patches and Program Awards ....................................................................................................... 12 Feed the Cold (a pre-CWLT assignment) ..................................................................................... 13 Sample Course Schedule (subject to change) ............................................................................... 14 Cold Weather Camping................................................................................................................ -

Shoe and Leather Encyclopedia;

TS 945 .S35 - Copy 1 Shoe "d Leather Encyclopedia ISSUED BY THE SHOE AND LEATHER GAZETTE SAINT LOUIS Shoes of Quality As a business man you know that a factory with a large output can produce an article of manufacture at less cost than can a factory with a small output. Therein lies the explanation of the unusual quality in American Lady and American Gentleman Shoes. They are made by the largest makers of shoes in the world. Their enormous purchases insure the best quality of materials at the lowest price. They get the best workmen—can employ the best designers—their selling expense must be less per shoe. All of this result in but one thing—the best shoes for the money. You get the benefit. The H B Idea "KEEP THE QUALITY UP " St. Louis m&k r Jb MB Boston Shoexo- TRADE MARK All Leather Shoes In all lines of shoes for men, women and children, the "All Leather" line brings the best results for the merchant :: :: Senate and Atlantic SHOES FOR MEN Pacific and Swell SHOES FOR WOMEN Red Goose School Shoes FOR BOYS AND GIRLS CATALOG ON REQUEST Friedman-Shelby Shoe Co. 1625 Washington Ave. - - ST. LOUIS COPYRIGHT 1911 TRADESMEN'S PUBLISHING CO. ©CI.A292164 SHOE and LEATHER ENCYCLOPEDIA A Book of Practical and Expert Testimony by Successful Merchants Each A rticle a Chapter Each Chapter a Single and Separate Subject PUBLISHED BY THE SHOE AND LEATHER GAZETTE SAINT LOUIS - ' ..-— - " " mm i n i ~ T The Nine O'Clock^ School Shoe Dealer is IS A Public Benefactor As He Aids in the Distribution of Free Flags to Schools Read all about this fascinating trade attraction in our special "Nine O'clock" Catalog. -

Frånfr Träsko Till Lacksko

FRÅN TRÄSKO TILL LACKSKO En studie om folkmusikaliskt lärande innanför och utanför musikutbildningar Olle Hansson Sara Lundbeck Uppsats HT 2011 Handledare: Johan Söderman Musikpedagogik I, avancerad nivå _________________________________________________________ Uppsatser på avancerad nivå vid Musikhögskolan, Örebro universitet Sammanfattning Titel: Från träsko till lacksko En studie om folkmusikaliskt lärande innanför och utanför musikutbildningar Title in English: From clog to dress shoe A study of folk musical learning within and outside music education Denna uppsats behandlar frågor såsom vad som kännetecknar lärande av folkmusik i en institutionell och en icke-institutionell miljö samt vad som händer när folkmusik träder in i musikutbildningar. Vad är det som påverkar låtförmedlingen i de olika miljöerna? Undersökningen har sin utgångspunkt i observationer och intervjuer med representanter från en institutionell respektive icke-institutionell miljö där vi har försökt att ta reda på upplevelser av miljön, stämning, roller och prestationer. Slutsatsen av undersökningen är att de två förmedlingssituationerna är mycket lika men att intentionerna skiljer sig. I den institutionella miljön är utgångspunkten att lära sig att spela och det finns en nyttoaspekt i lärandet av låtar där syftet är att på lång sikt utvecklas inom folkmusik i stort. Inom skolan finns ett ”läxtänkande” där studenten bär ansvar för att utanför lektionerna öva på låtarna och att även där göra sin egen musikaliska tolkning av dessa. I miljöer utanför skolan handlar -

Restructuring Crocs, Inc

RESTRUCTURING CROCS, INC. Turnaround Management Columbia Business School Advisor: Professor Laura Resnikoff April 26, 2010 Molly Bennard Kevin Sayles Ron Schulhof Julie Thaler John Wolff TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................ 2 INDUSTRY.....................................................................................................................................3 COMPANY...................................................................................................................................11 HISTORICAL FINANCIAL OVERVIEW...................................................................................22 DISCUSSION OF VALUATION ................................................................................................35 TURNAROUND PLAN ...............................................................................................................47 RECOMMENDATION.................................................................................................................51 EXHIBITS.....................................................................................................................................55 MARKETING MATERIAL……..................................................................................................65 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Crocs, Inc. is a designer, manufacturer and retailer of footwear for men, women and children. Crocs uses its proprietary closed cell-resin, Croslite, to make shoes -

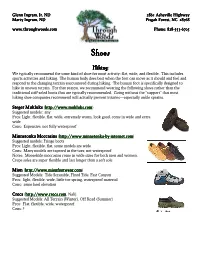

Shoes Throughwoods

Glenn Ingram, Jr, ND 2861 Asheville Highway Marty Ingram, ND Pisgah Forest, NC 28768 www.throughwoods.com Phone: 828828----553553553----67056705 Shoes HikingHiking:::: We typically recommend the same kind of shoe for most activity: flat, wide, and flexible. This includes sports activities and hiking. The human body does best when the foot can move as it should and feel and respond to the changing terrain encountered during hiking. The human foot is specifically designed to hike in uneven terrain. For that reason, we recommend wearing the following shoes rather than the traditional stiff-soled boots that are typically recommended. Going without the “support” that most hiking shoe companies recommend will actually prevent injuries—especially ankle sprains. Steger Mukluks ( http://www.mukluks.com ) Suggested models: any Pros: Light, flexible, flat, wide, extremely warm, look good, come in wide and extra wide Cons: Expensive, not fully waterproof Minnetonka Moccasins ( http://www.minnetonkahttp://www.minnetonka----bybybyby----internet.cominternet.com ) Suggested models: Fringe boots Pros: Light, flexible, flat, some models are wide Cons: Many models are tapered in the toes; not waterproof Notes: Moosehide moccasins come in wide sizes for both men and women. Crepe soles are super flexible and last longer than a soft sole Mion ( http://www.mionfootwear.com ) Suggested Models: Tide Scramble, Flood Tide, Fast Canyon Pros: light, flexible, wide, little toe spring, waterproof material Cons: some heel elevation Crocs (http://whttp://www.crocs.comww.crocs.com -

Visiting Yellowstone in Winter U.S

National Park Service Visiting Yellowstone in Winter U.S. Department of the Interior ellowstone is a special place, very different Observe wildlife Marvel at the Canyon from your home. Like any grand adventure, your Yellowstone journey will take you to Winter is a wonderful time to view wildlife. All the The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River extends Y large mammals present when Yellowstone became a from south of Canyon Village north to Tower impressive new locations and introduce you to new experiences. There are different risks here than you park are here today: grizzly and black bears, wolves, Junction. The most famous and spectacular section, may have faced before. You are responsible for mountain lions, elk, bison, pronghorn, moose, and including the Upper and Lower Falls can be seen your own safety. bighorn sheep. You’ll likely see several species of from the overlooks and trails of the Canyon area. birds, possibly bald eagles. On the road to adventure Pack your patience • Drive cautiously. The park speed limit is 45 mph Keep wildlife wild Traveling can be very stressful and it is easy to get (72 kph), unless posted otherwise. • Animals in Yellowstone are wild and dangerous. overwhelmed. Please use good manners and good • Icy and wet road conditions require extra • Bison, bears, and elk have injured and killed sense. attention. people. For your own safety, keep back and give them space to be wild. • Be prepared for a potential change in plans. • Watch out for wildlife on or near roadways. Allow time for delays due to weather or road • Stay 100 yards (91 m) away from wolves and • Use a road pullout if you need to stop for any conditions. -

View the SCA Dress Code

Seaside Christian Academy Dress Code *All clothing should fit properly, be free of stains, rips, and wrinkles.* SCA uniform shirts, gym uniforms, and outerwear (sweatshirts and fleeces) are purchased through our school uniform site https://seasidechristian.itemorder.com/sale. Pants, shorts, skirts, and jumpers must be uniform style and may be purchased at various retailers. Locally, uniform items may be purchased at The Children’s Place, Old Navy, Walmart, Target, Boscovs, and Kohls. You may also order online from French Toast, Lands’ End, Dickies, Ibiley Uniforms, and others. It is our goal to make purchasing uniforms easy and affordable for our families. When in doubt about whether something follows the dress code, please talk with the office staff BEFORE making a purchase or wearing it to school. Look for retailers that sell clothing designated as “uniform”. This will help with finding items that are the proper style and fit. Shirts ✓ SCA royal blue or gray uniform shirt ✓ High school students may choose from the approved uniform shirts on the online store. ✓ Shirts may be worn untucked but must be an appropriate length. ✓ NO long sleeve shirts or turtlenecks may be worn under a SCA uniform shirt. White undershirts may be worn under uniform shirts. ✓ SCA sweatshirts and fleeces may be worn in class but a uniform polo must be worn underneath. Solid navy and gray sweaters/sweatshirts are also permitted. Pants/Shorts ✓ Uniform style pants (cotton twill chinos or “Dockers”) in navy, tan (khaki) or black. ✓ NO cargo pants, jeans, stretch, knit, or skinny fit pants. ✓ Shorts must be KNEE LENGTH, hitting just above the knee (Bermuda style). -

Stepping Into History at the Bata Shoe Museum Zapatos Y Sociedad: Caminando Por La Historia En El Bata Shoe Museum

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert Shoes and Society: Stepping into History at the Bata Shoe Museum Zapatos y sociedad: caminando por la historia en el Bata Shoe Museum Elizabeth Semmelhack Senior Curator of the Bata Shoe Museum The Bata Shoe Museum 327, Bloor Street West Toronto (ON), Canadá M5S 1W7 [email protected] Recepción del artículo 19-07-2010. Aceptación de su publicación 17-08-2010 resumen. El Bata Shoe Museum de Toronto (Ca- abstract. The Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, nadá) es el museo de zapatos más grande de Nor- Canada is the largest shoe museum in North teamérica y alberga una colección de casi trece mil America and houses a collection of nearly 13,000 objetos que abarcan cuatro mil quinientos años de artifacts spanning 4,500 years of history. It is a cen- historia. Es, además, un centro internacional de in- tre for international academic research with a man- vestigación cuyo objetivo es el estudio, la exposi- date to study, exhibit, and publish on the cultural, ción y la publicación de trabajos académicos y cien- historical and sociological significance of footwear. tíficos sobre el significado cultural, histórico y -so The museum opened its doors to the public on ciológico del calzado. El museo abrió sus puertas May 6, 1995 and was established by Mrs. Sonja Bata al público el 6 de mayo de 1995 y fue fundado por as an independent, non-profit institution to house Sonja Bata como una institución independiente y and exhibit her renowned personal collection of sin ánimo de lucro cuya función primordial era al- historic and ethnographic footwear. -

The Magazine of Clogging Since 1983

The Magazine of Clogging Since 1983 TIMES DOUBLETOEwww.doubletoe.com December 2015 January 2016 Issue DOUBLETOE footprint December 2015 Our “Good Old Days” January 2016 Sometimes it is hard for me to imagine, but I have been involved in clogging and old time dance for 40 years. I started as a square dancer, and began clogging my first In This Issue year off college. I’ve seen so many changes in my time that the dance that I first encountered in the late 1970’s is Index ....................................................................2 hardly recognizable today. Footprint “Our Good Old Days” ...........................2 For those of us who were a part of the activity back then, Calendar of Events ..............................................4 today’s social media has become a means of sharing memories of those times and capturing the golden CLOG, Inc. National Clogging Convention ..........6 moments that are the time stamp of our “good old days.” Cloggers in the Spotlight: The term is certainly a cliché in popular culture. It usually is Students step up for Lancashire Lessons ......14 used when referring to an era considered by the presenter as being better than the current era. It is a form of nostalgia The Willis Clan...................................................16 and romanticism of a certain time. Percussive Dance History: For me and so many others who have been clogging for Buck, Flatfoot and Wings................................18 decades, we fondly look back on our “good old days” with an almost spiritual reverence. We cannot understand how Travelling Shoes: many of the young people of today could turn their noses Clogging at the Owl Cafe...................................24 up at the idea of clogging workshops and roll their eyes at Kriss Sands Flatfooting......................................26 the thought of an evening of fun dancing, mixers, square dancing and freestyling. -

Tuition Must Be Paid in Full by May 12, 2017

Dear Summer Intensive Student: We are so pleased that you have registered for BalletMet Dance Academy’s Summer Intensive 2017. We have enclosed for your review and completion, pertinent information and documentation. As you complete the required information, please use the REGISTRATION CHECKLIST to ensure that all of your paperwork is in order. These forms (*) should be completed in full and received along with the REGISTRATION CHECKLIST at BalletMet by April 14th. The following forms are enclosed: Registration Checklist* T-Shirt Order Form* $25.00 Press Release for Local Newspaper* What to Bring for Dance Classes Release and Treatment Authorization* Directions to BalletMet Regulations and Rules* Tips for you and your student Agreement to Release and Indemnify*(2 sided) OSU Medical Center – Sports Medicine Dept.) Reminder: Tuition must be paid in full by May 12, 2017 BalletMet Summer Intensive Studio Tours and Orientation: The BalletMet facility will be open for tours on Sunday, June 255h from 1:00 - 5:00 pm. Parent Orientations will be at 2:00 pm and 4:00 pm at BalletMet facility at 322 Mount Vernon Avenue. Placements: All students will arrive the first Monday, June 26, for a 9:00 am meeting and will be released at 5:15 pm. Students will be divided alphabetically. The Summer Intensive faculty will be assessing students in classes the first two days of the Intensive Program. Upon arriving Wednesday morning, students will receive their placement and will continue onto class. Classes: We will follow a regular class schedule beginning Wednesday, June 28. All students are expected to attend both morning and afternoon classes Monday through Friday. -

Seaside Christian Academy Dress Code *All Clothing Should Fit Properly, Be Free of Stains, Rips, and Wrinkles.*

Seaside Christian Academy Dress Code *All clothing should fit properly, be free of stains, rips, and wrinkles.* SCA uniform shirts, gym uniforms, and outerwear (sweatshirts and fleeces) are purchased through our school uniform site https://seasidechristian.itemorder.com/sale. Pants, shorts, skirts, and jumpers must be uniform style and may be purchased at various retailers. Locally, uniform items may be purchased at The Children’s Place, Old Navy, Walmart, Target, Boscovs, and Kohls. You may also order online from French Toast, Lands’ End, Dickies, Ibiley Uniforms, and others. It is our goal to make purchasing uniforms easy and affordable for our families. When in doubt about whether something follows the dress code, please talk with the office staff BEFORE making a purchase or wearing it to school. Look for retailers that sell clothing designated as “uniform”. This will help with finding items that are the proper style and fit. Shirts ✓ SCA royal blue uniform shirt ✓ High school students may choose from the approved uniform shirts on the online store. ✓ Shirts may be worn untucked but must be an appropriate length. ✓ NO long sleeve shirts or turtlenecks may be worn under a SCA uniform shirt. White undershirts may be worn under uniform shirts. ✓ SCA sweatshirts and fleeces may be worn in class but a uniform polo must be worn underneath. Solid navy sweaters are also permitted. Pants/Shorts ✓ Uniform style pants (cotton twill chinos or “Dockers”) in navy, tan (khaki) or black. ✓ NO cargo pants, jeans, stretch, knit, or skinny fit pants. ✓ Shorts must be KNEE LENGTH, hitting just above the knee (Bermuda style). -

Discovery Time, Wooden Shoes

Get Creative! Auaha-tia Research Kia hurahura Think E Whakaaro Discovery Time Ask 17 Paengawhāwhā | April 2020 Kia pātai A Special Pair of Shoes For our educator Mirjam whose family is in the Netherlands. Do you have loved ones far away? How do you keep in touch with them? Hi, I’m Pip. I have a small pair of hand-carved wooden children’s shoes, given to me by my mother. They are 17.5 cm long, 6.5cm wide and 4cm tall. I first remember them sitting on a shelf in our home when I was very young. I was SO small in fact, that when I first tried them on, they actually fitted me and I would clip-clop around. My mother had found them in an antique shop on Molesworth Street, Wellington. How they ended up there is a mystery, but luckily for us there are some clues to their history, written on the back of one of them, more than a hundred years ago! The oldest wooden shoe known was found in the Nieuwendijk in Amsterdam. This clog dates from Fun facts around the year 1230 and is made of alder wood. Wooden shoes are often called clogs. These are heavy work shoes that were typically worn by French, Dutch and Belgian peasants or farming people, until the Known in French as sabots, and in Dutch as klompen, beginning of the twentieth century. these sturdy shoes protected the feet of agricultural workers from mud and wet and from injury by the Historians have traced the origin of clogs to at least sharp tools used in the field.