Structural Adjustment and Sustainable Development in Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

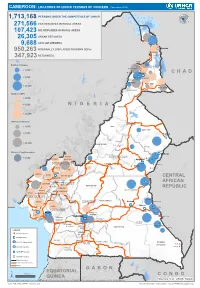

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Biomass Burning and Water Balance Dynamics in the Lake Chad Basin in Africa

Article Biomass Burning and Water Balance Dynamics in the Lake Chad Basin in Africa Forrest W. Black 1 , Jejung Lee 1,*, Charles M. Ichoku 2, Luke Ellison 3 , Charles K. Gatebe 4 , Rakiya Babamaaji 5, Khodayar Abdollahi 6 and Soma San 1 1 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO 64110, USA; [email protected] (F.W.B.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 Graduate Program, College of Arts & Sciences, Howard University, Washington, DC 20059, USA; [email protected] 3 Science Systems and Applications, Inc., Lanham, MD 20706, USA; [email protected] 4 Atmospheric Science Branch SGG, NASA Ames Research Center, Mail Code 245-5, ofc. 136, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA; [email protected] 5 National Space Research and Development Agency (NASRDA), PMB 437, Abuja, Nigeria; [email protected] 6 Faculty of Natural Resources and Earth Sciences, Shahrekord University, P.O. Box 115, Shahrekord 88186-34141, Iran; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-816-235-6495 Abstract: The present study investigated the effect of biomass burning on the water cycle using a case study of the Chari–Logone Catchment of the Lake Chad Basin (LCB). The Chari–Logone catchment was selected because it supplies over 90% of the water input to the lake, which is the largest basin in central Africa. Two water balance simulations, one considering burning and one without, were compared from the years 2003 to 2011. For a more comprehensive assessment of the effects of burning, albedo change, which has been shown to have a significant impact on a number of Citation: Black, F.W.; Lee, J.; Ichoku, environmental factors, was used as a model input for calculating potential evapotranspiration (ET). -

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N'djida

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape Northern Cameroon and Southwestern Chad April - May 2015 Paul Elkan, Roger Fotso, Chris Hamley, Soqui Mendiguetti, Paul Bour, Vailia Nguertou Alexandre, Iyah Ndjidda Emmanuel, Mbamba Jean Paul, Emmanuel Vounserbo, Etienne Bemadjim, Hensel Fopa Kueteyem and Kenmoe Georges Aime Wildlife Conservation Society Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (MINFOF) L'Ecole de Faune de Garoua Funded by the Great Elephant Census Paul G. Allen Foundation and WCS SUMMARY The Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape is located in north Cameroon and extends into southwest Chad. It consists of Bouba N’djida, Sena Oura, Benoue and Faro National Parks, in addition to 25 safari hunting zones. Along with Zakouma NP in Chad and Waza NP in the Far North of Cameroon, the landscape represents one of the most important areas for savanna elephant conservation remaining in Central Africa. Aerial wildlife surveys in the landscape were first undertaken in 1977 by Van Lavieren and Esser (1979) focusing only on Bouba N’djida NP. They documented a population of 232 elephants in the park. After a long period with no systematic aerial surveys across the area, Omondi et al (2008) produced a minimum count of 525 elephants for the entire landscape. This included 450 that were counted in Bouba N’djida NP and its adjacent safari hunting zones. The survey also documented a high richness and abundance of other large mammals in the Bouba N’djida NP area, and to the southeast of Faro NP. In the period since 2010, a number of large-scale elephant poaching incidents have taken place in Bouba N’djida NP. -

Cameroon Risk Profile

019 2 DISASTER RISK PROFILE Flood Drought Cameroon Building Disaster Resilience to Natural Hazards in Sub-Saharan African Regions, Countries and Communities This project is funded by the European Union © CIMA Research Foundation PROJECT TEAM International Centre on Environmental Monitoring Via Magliotto 2. 17100 Savona. Italy Authors Roberto Rudari [1] 2019 - Review Amjad Abbashar [2] Sjaak Conijn [4] Africa Disaster Risk Profiles are co-financed by the Silvia De Angeli [1] Hans de Moel [3] EU-funded ACP-EU Natural Disaster Risk Reduction Auriane Denis-Loupot [2] Program and the ACP-EU Africa Disaster Risk Financing Luca Ferraris [1;5] Program, managed by UNDRR. Tatiana Ghizzoni [1] Isabel Gomes [1] Diana Mosquera Calle [2] Katarina Mouakkid Soltesova [2] DISCLAIMER Marco Massabò [1] Julius Njoroge Kabubi [2] This document is the product of work performed by Lauro Rossi [1] CIMA Research Foundation staff. Luca Rossi [2] The views expressed in this publication do not Roberto Schiano Lomoriello [2] Eva Trasforini [1] necessarily reflect the views of the UNDRR or the EU. The designations employed and the presentation of the Scientific Team material do not imply the expression of any opinion Nazan An [7] Chiara Arrighi [1;6] whatsoever on the part of the UNDRR or the EU Valerio Basso [1] concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city Guido Biondi [1] or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the Alessandro Burastero [1] Lorenzo Campo [1] delineation of its frontiers or boundaries. Fabio Castelli [1;6] Mirko D'Andrea [1] Fabio Delogu [1] Giulia Ercolani[1;6] RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Elisabetta Fiori [1] The material in this work is subject to copyright. -

Livelihood Strategies in African Cities: the Case of Residents in Bamenda, Cameroon Nathanael Ojong

African Review of Economics and Finance, Vol. 3, No.1, Dec 2011 ©The Author(s) Journal compilation ©2011 African Centre for Economics and Finance. Published by Print Services, Rhodes University, P.O. Box 94, Grahamstown, South Africa. Livelihood Strategies in African Cities: The Case of Residents in Bamenda, Cameroon Nathanael Ojong Abstract This paper analyses the livelihood strategies of residents in the city of Bamenda, Cameroon. It argues that the informal economy is not the preserve of the poor. Middle income households also play a crucial role. Informal economic activities permit the middle class to diversify their sources of income as well as accumulate capital. It examines the role of class in the informal economy and analyses the impact of policy on those involved in informal economic activities. The paper reveals that formality, informality and policy are intertwined, thus making livelihood strategies in cities complex. Key words: City, Livelihood, Bamenda, Informal, Income 1. Introduction After independence, Cameroon enjoyed relative prosperity until 1985. From 1970 to 1985, its economy grew annually at over 8 per cent (Page, 2002, p.44). This growth was mostly due to the boom in the exportation of cash crops. In 1977, cash crops made up 72 per cent (71.9 per cent) of exports while oil was 1.4 per cent (Page, 2002, p.44). This situation changed in the 1980s as a result of oil exploration. In 1985 oil made up 65.4 per cent and cash crops 21.4 per cent of exports, with government getting high royalties from international oil companies developing the field (Page, 2002, p.44). -

CMR-3W-Cash-Transfer-Partners V3.4

CAMEROON: 3W Operational Presence - Cash Programming [as of December 2016] Organizations working for cash 10 programs in Cameroon Organizations working in Organizations by Cluster Food security 5 International NGO 5 Multi-Sector cash 5 Government 2 Economic Recovery 3 Red Cross & Red /Livelihood 2 Crescent Movement Nutrition 1 UN Agency 1 WASH 1 Number of organizations Multi-Sector Cash by departments 15 5 distinct organizations 9 organizations conducting only emergency programs 1 organizations conducting only regular programs Number of organizations by departments 15 Economic Recovery/Livelihood Food security 3 distinct organizations 5 distinct organizations Number of organizations Number of organizations by department by department 15 15 Nutrition WASH 3 distinct organizations 1 organization Number of organizations Number of organizations by department by department 15 15 Creation: December 2016 Sources: Cash Working group, UNOCHA and NGOs More information: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/cameroon/cash )HHGEDFNRFKDFDPHURRQ#XQRUJ 7KHERXQGDULHVDQGQDPHVVKRZQDQGWKHGHVLJQDWLRQVXVHGRQWKLVPDSGRQRWLPSO\RI̙FLDOHQGRUVHPHQWRUDFFHSWDQFHE\WKH8QLWHG1DWLRQV CAMEROON:CAMEROON: 3W Operational Presence - Cash Programming [as of December 2016] ADAMAOUA FAR NORTH NORTH 4 distinct organizations 9 distinct organizations 1 organization DJEREM DIAMARE FARO MINJEC CRF MINEPAT CRS IRC MAYO-BANYO LOGONE-ET-CHARI MAYO-LOUTI MINEPAT MINEPAT WFP, PLAN CICR MMBERE MAYO-REY PLAN PUI MINEPAT CENTRE MAYO-DANAY 1 organization MINEPAT LITTORAL 1 organization -

The River Logone: a Mixed-Blessing to the Inhabitants of Mayo Danay

SYLLABUS Revue scientifique interdisciplinaire de l’École Normale Supérieure Série Lettres et sciences humaines Numéro spécial volume VII N° 1 2016 THE RIVER LOGONE: A MIXED-BLESSING TO THE INHABITANTS OF MAYO DANAY DIVISION, FAR-NORTH REGION OF CAMEROON TAKEM MBI Bienvenu Magloire National Institute of Cartography, P.O. Box 157, INC, Yaoundé [email protected] Abstract This paper sought to know if the constant supply of water to the River Logone, in a very low altitude area, from the wet tropical highlands in central Cameroon and the Adamawa plateau is a mixed- blessing to the inhabitants of Mayo Danay. Data was gathered through field enquiry and discussions with administrative authorities in October 2014. Results depict that a number of activities like farming, fishing, animal rearing and transport in the area depend on the River Logone despite that it is a source of floods and facilitates the spreading of malaria parasite. Conclusively, it is actually a mixed- blessing to the people, necessitating measures to make it less hazardous. Key-Words: Far North Cameroon, Floods, Mayo Danay, River Logone. Résumé Cet article permet de savoir si l’approvisionnement constant en eau du fleuve Logone à partir des hautes montagnes tropicales du centre du Cameroun et du plateau de l’Adamaoua vers une zone de basse altitude est une source de vie ou de désastre pour les habitants du 217 TAKEM MBI Bienvenu Magloire / SYLLABUS NUMERO SPECIAL VOL VII N° 1, 2016 : 217 - 242 THE RIVER LOGONE: A MIXED-BLESSING TO THE INHABITANTS OF MAYO DANAY DIVISION, FAR-NORTH REGION OF CAMEROON Mayo Danay. -

The Case of the Cameroonian Cocoa Industry Value Chain

Competitiveness in the Cash Crop Sector: The Case of the Cameroonian Cocoa Industry Value Chain Abei L¹, Van Rooyen J¹ ¹Stellenbosch University Corresponding author email: [email protected] Abstract: Since independence, the cocoa industry of Cameroon has gone through various phases suffering from deregulation of the industry, globalisation, trade liberalisation, natural disasters etc. This paper aims at analysing the competitive performance of a very tradeable global commodity and the main export crop of Cameroon from 1961 to 2013 through the application of a step-wise analytical framework adapted from ISMEA, (1999); Esterhuizen, (2006); Van Rooyen and Esterhuizen (2012) accommodating aspects of agri- value chain analysis. This conventional analysis was expanded to include value chain comparisons between various value- adding processes in the Cameroonian cocoa value chain as well as consensus vs. variations in opinions of different actors within the cocoa industry regarding the factors influencing the industry’s competitive performance from the application of the Porter Diamond model. Information from chain actors through the cocoa executive survey (CES) was used to further expand the framework and analyse the relationship between the various factors affecting the industry’s performance i.e. identify factors which are interrelated in influencing the industry and those that show a degree of independence. Such information is viewed as facilitative for strategic planning purposes. Results revealed that three Porter determinants positively influence the industry’s performance while two were constraining implying that the Cameroon cocoa industry, while performing positively, can strive to increase competitiveness considerably by applying selected industry-based strategies. Keywords: Cameroonian cocoa industry, competitive performance, relative trade advantage (RTA), cocoa executive survey (CES), Porter Diamond. -

Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin

127 WHITE FULANI CATTLE OF WEST AND CENTRAL AFRICA C.L. Tawah' and J.E.O. Rege2 'Centre for Animal and Veterinary Research. P.O. Box 65, Ngaoundere, Adamawa Province, CAMEROON 2International Livestock Research Institute, P.O. Box 5689, Addis Ababa, ETHIOPIA SUMMARY The paper reviews information on the White Fulani cattle under the headings: origin, classification, distribution, population statistics, ecological settings, utility, husbandry practices, physical characteristics, special genetic characteristics, adaptive attributes and performance characteristics. It was concluded that the breed is economically important for several local communities in many West and Central African countries. The population of the breed is substantial. However, introgression from exotic cattle breeds as well as interbreeding with local breeds represent the major threat to the breed. The review identified a lack of programmes to develop the breed as being inimical to its long-term existence. RESUME L'article repasse l'information sur la race White Fulani du point de vue: origine, classement, distribution, statistique de population, contexte écologique, utilité, pratiques de conduites, caractéristiques physiques, caractéristiques génétiques spéciales, adaptabilité, et performances. On conclu que la race est importante du point de vue économique pour diverses communautés rurales dans la plupart des régions orientales et centrale de l'Afrique. Le nombre total de cette race est important; cependant, l'introduction de races exotiques, ainsi que le croisement avec des races locales représente le risque le plus important pour cette race. Cet article souligne également le fait que le manque de programmes de développement à long terme représente un risque important pour la conservation de cette race. -

Review of River Fisheries Valuation in West and Central Africa by Arthur

Neiland and Béné ___________________________________________________________________________________ Review of River Fisheries Valuation in West and Central Africa by Arthur Neiland (1) & Christophe Béné (2) IDDRA (Institute for Sustainable Development & Aquatic Resources) Portsmouth Technopole Kingston Crescent Portsmouth PO2 Hants United Kingdom Tel: +44 2392 658232 E-mail: [email protected] CEMARE (Centre for the Economics & Management of Aquatic Resources) University of Portsmouth Locksway Road Portsmouth PO4 8JF Hants United Kingdom Tel: +44 2392 844116 1 E-mail: [email protected] 1 Dr Bene is now at the World Fish Center 1 Neiland and Béné ___________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT This paper provides a review of the valuation of river fisheries in West and Central Africa. It is the general perception that compared to the biological and ecological aspects of river fisheries, this particular subject area has received comparatively little attention. Economic valuation is concerned with finding expression for what is important in life for human society. It should therefore be a central and integral part of government decision-making and policy. The paper starts with a review of concepts and methods for valuation. Three main types of valuation techniques are identified: conventional economic valuations, economic impact assessments and socio-economic investigations and livelihood analysis. On the basis of a literature review, valuation information was then synthesised for the major regional river basins and large lakes, and also used to develop a series of national fisheries profiles. To supplement this broad perspective, a series of case-studies are also presented, which focus in particular on the impact of changes in water management regime. Finally, the paper presents an assessment of the three main types of valuation methodology and a set of conclusions and recommendations for future valuation studies. -

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa povertydata.worldbank.org Poverty & Equity Brief Sub-Saharan Africa Angola April 2020 Between 2008-2009 and 2018-2019, the percent of people below the national poverty line changed from 37 percent to 41 percent (data source: IDR 2018-2019). During the same period, Angola experienced an increase in GDP per capita followed by a recession after 2014 when the price of oil declined. Based on the new benchmark survey (IDREA 2018-2019) and the new national poverty line, the incidence of poverty in Angola is at 32 percent nationally, 18 percent in urban areas and a staggering 54 percent in the less densely populated rural areas. In Luanda, less than 10 percent of the population is below the poverty line, whereas the provinces of Cunene (54 percent), Moxico (52 percent) and Kwanza Sul (50 percent) have much higher prevalence of poverty. Despite significant progress toward macroeconomic stability and adopting much needed structural reforms, estimates suggest that the economy remained in recession in 2019 for the fourth consecutive year. Negative growth was driven by the continuous negative performance of the oil sector whose production declined by 5.2 percent. This has not been favorable to poverty reduction. Poverty is estimated to have increased to 48.4 percent in 2019 compared to 47.6 percent in 2018 when using the US$ 1.9 per person per day (2011 PPP). COVID-19 will negatively affect labor and non-labor income. Slowdown in economic activity due to social distancing measures will lead to loss of earnings in the formal and informal sector, in particular among informal workers that cannot work remotely or whose activities were limited by Government. -

Folk Knowledge of Fish Among the Kotoko of Logone-Birni

Ministry of Scientific Research and Innovation Folk Knowledge of Fish Among the Kotoko of Logone-Birni Aaron Shryock [DRAFT CIRCULATED FOR COMMENT] SIL B.P. 1299, Yaoundé Cameroon [email protected] (237) 77.77.15.98 (237) 22.17.17.82 2009 Abbreviations ad. adult adl. large adult ads. subadult cf. refer to ex. excluding fem. female juv. juvenile juvl. large juvenile mal. male n. noun n.f. feminine noun n.f.pl. noun which may be feminine or plural without any overt change in its shape n.m. masculine noun n.m.f. noun which may be masculine or feminine without any overt change in its shape n.m.f.pl. noun which may be masculine, feminine, or plural without any overt change n.m.pl. noun which may be masculine or plural without any overt change in its shape n.pl. plural noun pl. plural sg. singular sp. species spp. species, plural syn. synonym TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations........................................................................................................................................i 1. Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 1.1 The purpose of the study and the methods.............................................................................................. 1 1.2 The Kotoko and their language ............................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Fish fauna...............................................................................................................................................