Pediatric Status Epilepticus Pathway-FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

Non-Epileptic Seizures a Short Guide for Patients and Families

Non-epileptic seizures a short guide for patients and families Department of Neurology Information for patients Royal Hallamshire Hospital What are non-epileptic seizures? In a seizure people lose control of their body, often causing shaking or other movements of arms and legs, blacking out, or both. Seizures can happen for different reasons. During epileptic seizures, the brain produces electrical impulses, which stop it from working normally. Non-epileptic seizures look a little like epileptic seizures, but are not caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Non-epileptic seizures happen because of problems with handling thoughts, memories, emotions or sensations in the brain. Such problems are sometimes related to stress. However, they can also occur in people who seem calm and relaxed. Often people do not understand why they have developed non-epileptic seizures. Are non-epileptic seizures rare? For every 100,000 people, between 15 and 30 have non- epileptic seizures. Nearly half of all people brought in to hospital with suspected serious epilepsy turn out to have non- epileptic seizures instead. One of the reasons why you may not have heard of non- epileptic seizures is that there are several other names for the same problem. Non-epileptic seizures are also known as pseudoseizures, psychogenic, dissociative or functional seizures. Sometimes people who have non-epileptic seizures are told that they suffer from non-epileptic attack disorder (NEAD). How can I be sure that this is the right diagnosis? Non-epileptic seizures often look like epileptic seizures to friends, family members and even doctors. Like epilepsy, non- epileptic seizures can cause injuries and loss of control over bladder function. -

An Atypical Presentation of Epilepsy; What a Headache! J Neurol Transl Neurosci 5(1): 1078

Central Journal of Neurology & Translational Neuroscience Bringing Excellence in Open Access Case Report Corresponding author Sarah Seyffert, Trinity School of Medicine, 505 Tadmore court Schaumburg, Illinois 60194, USA, Tel: 847-217-4262; An Atypical Presentation of Email: Submitted: 13 April 2017 Epilepsy; What a Headache! Accepted: 07 June 2017 Published: 09 June 2017 Sarah Seyffert* and Wade Kvatum ISSN: 2333-7087 Trinity School of Medicine, USA Copyright © 2017 Seyffert et al. Abstract OPEN ACCESS The relationship between headache and seizure is a poorly understood and controversial topic; however, the literature has recently suggested that the two conditions may be related. Keywords The interplay between these conditions seems to be even more complex in a group of • Epilepsy patients with epilepsy related headaches. It has been proposed that the association could • Headache be classified into preictal, ictal, postictal, or interictal headaches. Here we present a case • Ictal epileptic headache report of a 62 year old male who presented with a chief complaint of new onset severe headache and subsequently underwent multiple diagnostic testing modalities before he was finally diagnosed and treated for epilepsy, which lead to the resolution of his headache. We conclude with a short discussion of how to subcategorize seizure related headaches based on their temporal relationship and why they can pose such a difficult diagnostic challenge. ABBREVIATIONS afebrile with a normal CBC and CMP. On arrival to the hospital he underwent a non-contrast head CT scan; however, no evidence of EEG: Electroencephalogram; CBC: Complete Blood Count; acute intracranial abnormality was seen. Additionally, a lumbar CMP: Complete Metabolic Panel; CT scan: Computerized puncture was performed which was negative for xanthochromia Tomography Scan; CTA: Computed Tomographic Angiography; and showed a protein count of 27, glucose 230, and 2 white MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging blood cells. -

The Migraine-Epilepsy Syndrome

medigraphic Artemisaen línea Arch Neurocien (Mex) Vol 11, No. 4: 282-287, 2006 The Migraine- Epilepsy Syndrome Arch Neurocien (Mex) Vol. 11, No. 4: 282-287, 2006 Artículo de revisión ©INNN, 2006 de caso The migraine-epilepsy syndrome Enrique Otero Siliceo†, Fernando Zermeño EL SINDROME MIGRAÑA-EPILEPSIA represent a neural exitation. Since that the glutamate has in important rol in both patologys depending of the part of the brain more affected the symptoms might RESUMEN vary from visual to abdominal phemomena. La migraña y la epilepsia tienen varios puntos en común Key words: migraine epilepsy, EEG abnormalities, sintomática clínica y genéticamente lo que ha sido glutamate, diagnosis. postulado por más de cien años. El fenómeno referido como migraña-epilepsia sugiere que exista una he first steps of a practical, approach by patofisiología común. El síndrome de migraña o physicians in recognizing and treating neuro- epilepsia tiene fenómenos comunes de dolor adominal T logic diseases are to recognithat there are jaqueca anormalidades del EE y respuesta a droga various overlaps between migraine and epilepsy. antiepilépticas. En ocasiones el paciente puede tener Epileptic seizures and classic migraine episodes may un ataque migrañoso o una convulsión o en otras occur in the same patient. Migraine and epilepsy share ambas. La comorbilidad puede explicarse por estados several genetic, clinical, evolutive and neurophysio- de hiperrexcitabilidad neural. Alteraciones electroen- logic features. A relationship between epilepsy and cefalográficas son comunes en estos estados. En migraine has been postulated for over a hundred years apariencia el glutamato tiene un papel importante tanto and the syndrome of Migraine-Epilepsy illustrates this en la migraña como en la epilepsia. -

Migraine Triggered Seizures and Epilepsy Triggered Headache and Migraine Attacks: a Need for Re-Assessment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central J Headache Pain (2011) 12:287–288 DOI 10.1007/s10194-011-0344-2 COMMENTARY Migraine triggered seizures and epilepsy triggered headache and migraine attacks: a need for re-assessment Paul T. G. Davies • C. P. Panayiotopoulos Received: 5 April 2011 / Accepted: 8 April 2011 / Published online: 24 April 2011 Ó The Author(s) 2011. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com In this issue of the Journal, Belcastro and associates review Migralepsy terminology and classification issues for migralepsy, hem- icrania epileptica, post-ictal and ictal headache [1]. They According to the ICHD-II 1.5.5, ‘‘migraine-triggered sei- raise key points such as ictal headache and visual seizures zure (sometimes referred to as migralepsy)’’ denotes an are often misdiagnosed as migraine, ‘‘migralepsy’’ is unli- epileptic seizure that occurs ‘‘during or within one hour kely to exist and an ‘‘epilepsy-migraine sequence’’ is much after a migraine aura’’ [3]. However, the evidence of this more common and well documented than the dominant ‘‘migraine-seizure’’ sequence is weak and the proposed view of a ‘‘migraine-epilepsy sequence’’. Their relevant criterion of 1 h gap between the end of the ‘‘aura’’ and the proposals need appropriate attention by the committee of start of an epileptic seizure is entirely arbitrary the international classification of headache disorders Migralepsy is an old term derived from migra(ine) and (ICHD) as well as the physicians in their clinical practice (epi)lepsy, coined by Dr Douglas Davidson, but mainly because of the consequences that misdiagnosis may have on attributed to Lennox and Lennox, which we quote, ‘‘a patients. -

Seizure Triggers

SEIZURE TRIGGERS M A R I A R AQUEL LOPEZ. M.D M I A M I V H A DEFINITION OF SEIZURE VS. EPILEPSY • Epileptic seizure: Is a transient symptom of abnormal excessive electric activity of the brain. EPILEPSY • More than one epileptic seizure. TYPE OF SEIZURES ETIOLOGY • Epilepsy is a heterogeneous condition with varying etiologies including: 1. Genetic 2. Infectious 3. Trauma 4. Vascular 5. Neoplasm 6. Toxic exposures TRIGGERS FOR EPILEPTIC SEIZURES • What is a seizure trigger? It is a factor that can cause a seizure in a person who either has epilepsy or does not. • Factors that lead into a seizure are complex and it is not possible to determine the trigger in each patient. TRIGGERS A. Most common ones Stress Missing taking the medication THE MOST OFTEN REPORTED BY PATIENTS • Sleep deprivation and tiredness • Fever OTHER COMMON CAUSES . Infection . Fasting leading into hypoglycemia. Caffeine: particularly if it interrupts normal sleep patterns. Other medications like hormonal replacement, pain killers or antibiotics. OTHER TRIGGERS External precipitants • Alcohol consumption or withdrawal. *Specific triggers that are related to Reflex epilepsy Bathing Eating Reading OTHER TRIGGERS • Flashing light: especially with patients with idiopathic generalized seizure disorder STRESS . Stress is the most common patient –perceived seizure precipitant, studies of life events suggest that stressful experiences trigger seizures in certain individuals. Animals epilepsy models provide more convincing evidence that exposure to exogenous and endogenous stress mediators has been found to increase epileptic activity in the brain, especially after repeating exposure. SOLUTION ABOUT STRESS • Intervention of copying with stress STRESS MANAGEMENT • Include trying to get in a place of peace utilizing multiple techniques: • Regular exercise • Yoga and medication • Therapy or psychological support with a provider. -

Myoclonic Status Epilepticus in Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

Original article Epileptic Disord 2009; 11 (4): 309-14 Myoclonic status epilepticus in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy Julia Larch, Iris Unterberger, Gerhard Bauer, Johannes Reichsoellner, Giorgi Kuchukhidze, Eugen Trinka Department of Neurology, Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria Received April 9, 2009; Accepted November 18, 2009 ABSTRACT – Background. Myoclonic status epilepticus (MSE) is rarely found in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) and its clinical features are not well described. We aimed to analyze MSE incidence, precipitating factors and clini- cal course by studying patients with JME from a large outpatient epilepsy clinic. Methods. We retrospectively screened all patients with JME treated at the Department of Neurology, Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria between 1970 and 2007 for a history of MSE. We analyzed age, sex, age at seizure onset, seizure types, EEG, MRI/CT findings and response to antiepileptic drugs. Results. Seven patients (five women, two men; median age at time of MSE 31 years; range 17-73) with MSE out of a total of 247 patients with JME were identi- fied. The median follow-up time was seven years (range 0-35), the incidence was 3.2/1,000 patient years. Median duration of epilepsy before MSE was 26 years (range 10-58). We identified three subtypes: 1) MSE with myoclonic seizures only in two patients, 2) MSE with generalized tonic clonic seizures in three, and 3) generalized tonic clonic seizures with myoclonic absence status in two patients. All patients responded promptly to benzodiazepines. One patient had repeated episodes of MSE. Precipitating events were identified in all but one patient. Drug withdrawal was identified in four patients, one of whom had additional sleep deprivation and alcohol intake. -

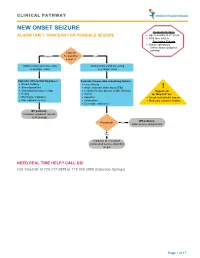

Seizure, New Onset

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

Emergency Department Management of Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. -, No. -, pp. 1–4, 2016 Ó 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 0736-4679/$ - see front matter http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.10.042 Selected Topics: Psychiatric Emergencies PSYCHIATRIC EMERGENCIES FOR CLINICIANS: EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT MANAGEMENT OF NEUROLEPTIC MALIGNANT SYNDROME Michael P. Wilson, MD, PHD,*† Gary M. Vilke, MD,*† Stephen R. Hayden, MD,* and Kimberly Nordstrom, MD, JD‡§ *University of California at San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, California, †Department of Emergency Medicine Behavioral Emergencies Research (DEMBER) Laboratory, University of California San Diego, San Diego, California, ‡Denver Health Medical Center, Department of Behavioral Health, Psychiatric Emergency Service, Denver, Colorado, and §University of Colorado Denver, School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado Reprint Address: Michael P. Wilson, MD, PHD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California at San Diego Medical Center, 200 West Arbor Drive, Mail Code #8676, San Diego, CA, 92103 , Keywords—altered mental status; neuroleptic malig- What Do You Think is Going on with This Patient? nant syndrome; dystonia; catatonia; rigidity The clinical presentation suggests neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). Although first described more than 50 years ago, the diagnosis of NMS is primarily CLINICAL SCENARIO clinical (1). A 25-year-old man presents with a recent diagnosis of schizophrenia. He was discharged 1 week earlier from What Key Findings Lead to the Diagnosis? an inpatient psychiatric unit. His mother states that he has been acting ‘‘differently’’ for the past 2 days. He Clues to an NMS diagnosis include a recent diagnosis of a has not been ‘‘making any sense,’’ has felt warm to the psychotic disorder and inpatient psychiatric hospitaliza- touch, and today has been stiff and moving rigidly like tion. -

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions N Specchio1, EC Wirrell2*, IE Scheffer3, R Nabbout4, K Riney5, P Samia6, SM Zuberi7, JM Wilmshurst8, E Yozawitz9, R Pressler10, E Hirsch11, S Wiebe12, JH Cross13, P Tinuper14, S Auvin15 1. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. University of Melbourne, Austin Health and Royal Children’s Hospital, Florey Institute, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. 4. Reference Centre for Rare Epilepsies, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital, APHP, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Institut Imagine, INSERM, UMR 1163, Université de Paris, Paris, France. 5. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 6. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 7. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Refence Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 8. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 9. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 10. Programme of Developmental Neurosciences, UCL NIHR BRC Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK 11. -

Epilepsy After Stroke

Stroke Helpline: 0303 3033 100 Website: stroke.org.uk Epilepsy after stroke In the first few weeks after a stroke some people have a seizure, and a small number go on to develop epilepsy – a tendency to have repeated seizures. These can usually be completely controlled with treatment. This factsheet explains what epilepsy is, the different types of seizures, and how epilepsy is diagnosed and treated. It also includes advice about coping with a seizure, and a glossary. Epilepsy is a tendency to have repeated What causes seizures? seizures – sometimes called ‘fits’ or ‘attacks’. It affects just under one per cent Cells in the brain communicate with one of people in the UK. Stroke is one of many another and with our muscles by passing conditions that can lead to epilepsy. electrical signals along nerve fibres. If you have epilepsy this electrical activity can Around five per cent of people who have a become disordered. A sudden abnormal stroke will have a seizure within the following burst of electrical activity in the brain can few weeks. These are known as acute or lead to a seizure. onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke. You are more likely There are over 40 different types of seizures to have one if you have had a severe stroke, ranging from tingling sensations or ‘going a stroke caused by bleeding in the brain (a blank’ for a few seconds, to shaking and haemorrhagic stroke), or a stroke involving losing consciousness. the part of the brain called the cerebral cortex. If you have an onset seizure, it This can mean that epilepsy is sometimes does not necessarily mean you have or will confused with other conditions, including develop epilepsy. -

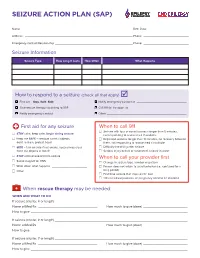

Seizure Action Plan (Sap)

SEIZURE ACTION PLAN (SAP) Name: ——————————————————————————————————————————————————— Birth Date: ——————————————————— Address: —————————————————————————————————————————————————— Phone: ————————————————————— Emergency Contact/Relationship ———————————————————————————————————— Phone: ————————————————————— Seizure Information Seizure Type How Long It Lasts How Often What Happens How to respond to a seizure (check all that apply) F First aid – Stay. Safe. Side. F Notify emergency contact at ______________________________ F Give rescue therapy according to SAP F Call 911 for transport to __________________________________________ F Notify emergency contact F Other ________________________________________________ First aid for any seizure When to call 911 F Seizure with loss of consciousness longer than 5 minutes, F STAY calm, keep calm, begin timing seizure not responding to rescue med if available F Keep me SAFE – remove harmful objects, F Repeated seizures longer than 10 minutes, no recovery between don’t restrain, protect head them, not responding to rescue med if available F SIDE – turn on side if not awake, keep airway clear, F Difficulty breathing after seizure don’t put objects in mouth F Serious injury occurs or suspected, seizure in water F STAY until recovered from seizure When to call your provider first F Swipe magnet for VNS F Change in seizure type, number or pattern F Write down what happens _____________________ F Person does not return to usual behavior (i.e., confused for a F Other _____________________________________ long