Pesant Revolt in Madras Presidency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Author of Summaries- Contemporary of Buddhaghosa

UNIVERSITY OF CEYLON REVIEW The Great Author of Summaries- Contemporary of Buddhaghosa UDDHADATTA'S Manuals of Vinaya and Abhidhamma are now known to orientalists through the editions of the Pali Text B Society. I In the Introductory Note to the Abhidhammavatiira, Mrs. C. A. F. Rhys Davids remarks: "According to the legend, Buddhadatta recast in a condensed shape that which Buddhaghosa handed on, in Pali, from the Sinhalese Commentaries. But the psychology and philosophy are pre- sented through the prism of a second vigorous intellect, under fresh aspects, in a style often less discursive and more graphic than that of the great Com- msntator, and with strikingly rich vocabulary, as is revealed by the dimensions of the Index. .. So little was the modestly expressed ambition of Buddha- datta's Commentator realized :-that the great man's death would leave others room to emerge from eclipse-a verse that forcibly recalls George Meredith's quip uttered at Tennyson's funeral-' Well, a -, it's a great day for the minor poets'!" The legend that she refers to is found in the Pali Commentary on the Vina- yavinicchaya and in the Buddhaghosu-p paiti, The former work was composed by the Sinhalese Elder, Mahasami Vacissara, in about the r zth century A.D., and is still unpublished. In its introduction it states: "Ayarn kira Bhadanta- Buddhadatt acariyo Lankadlpato sajatibhfimin Jambudipam agacchanto Bhadanta-Buddhaghosacariyau J ambudipavasikehi . mahatheravarehi kataradhanan Sihalatthakathan parivattetva . miilabhasaya tipitaka- pariyattiya atthakatham likhitum Lankadlpam gacchantam antar amagge disva sakacchaya samupaparikkhitva ... balavaparitosam patva ... 'tumhe yathadhippeta-pariyantarn likhitam atthakatham amhakam pesetha, mayam assa pan a .. -

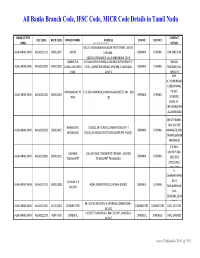

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 54.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 41] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2013 Aippasi 6, Vijaya, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 2893-3026 Notice .. 3026-3028 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 43888. My son, D. Ramkumar, born on 21st October 1997 43891. My son, S. Antony Thommai Anslam, born on (native district: Madurai), residing at No. 4/81C, Lakshmi 20th March 1999 (native district: Thoothukkudi), residing at Mill, West Colony, Kovilpatti, Thoothukkudi-628 502, shall Old No. 91/2, New No. 122, S.S. Manickapuram, Thoothukkudi henceforth be known as D. RAAMKUMAR. Town and Taluk, Thoothukkudi-628 001, shall henceforth be G. DHAMODARACHAMY. known as S. ANSLAM. Thoothukkudi, 7th October 2013. (Father.) M. v¯ð¡. Thoothukkudi, 7th October 2013. (Father.) 43889. I, S. Salma Banu, wife of Thiru S. Shahul Hameed, born on 13th September 1975 (native district: Mumbai), 43892. My son, G. Sanjay Somasundaram, born residing at No. 184/16, North Car Street, on 4th July 1997 (native district: Theni), residing Vickiramasingapuram, Tirunelveli-627 425, shall henceforth at No. 1/190-1, Vasu Nagar 1st Street, Bank be known as S SALMA. -

TNEB LIMITED TANGEDCO TANTRANSCO BULLETIN December

1 TNEB LIMITED TANGEDCO TANTRANSCO BULLETIN December – 2018 CONTENTS Page No 1. PART – I NEWS & NOTES … … … 2 2. PART – II GENERAL ADMINISTRATIVE & SERVICES … … … 8 3. PART – III FINANCE … … … 21 4. PART – IV TECHNICAL … … … 33 5. INDEX … … … 55 6. CONSOLIDATED INDEX … … … 59 A request With the present issue of the TANGEDCO Bulletin for December 2018 Volume XXXVII (37) which completed. The recipients of the Bulletin are request to have the 12 issues of Volume XXXVII bound in one part from January 2018 to December 2018. A consolidated Index for volume XXXVII has been included in this issue for reference. 2 NEWS & NOTES PART – I I. GENERATION/RELIEF PARTICULARS:- The Generation/Relief particulars for the month of December 2018 were as follows: Sl.No Particulars In Million Units I. TNEB GENERATION (Gross) Hydro 488.582 Thermal 2318.235 Gas 145.094 Wind 0.100 TNEB TOTAL 2952.011 II. NETT PURCHASES FROM CGS 2730.033 III. PURCHASES IPP 221.921 Windmill Private 243.604 CPP, Co- generation & Bio-Mass (Provisional) 16.500 Solar (Private) 274.640 Through Traders (nett purchase) 1758.316 TOTAL PURCHASES 2514.981 IV. Total Wheeling Quantum by HT consumers 702.424 Total Wheeling Quantum to Other States by Pvt. Generators 11.053 Total TNEB Power generation for sale 0.000 TOTAL WHEELING 713.477 Power Sale by TANGEDCO (Exchange) 0.000 Power Sale by TANGEDCO (STOA under Bilateral) 0.000 Power Sale by Private Generators (Exchange) (-)8.403 Power Sale by Private Generators (Bilateral) (-)2.650 Power balance under SWAP 2.688 V. TOTAL (TNEB Own Gen + Purchase + wheeling quantum + SWAP) 8902.138 VI. -

1. Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION Biodiversity refers to the variability of life all the living species of animals, plants and microorganisms on earth. According to Hawksworth (2002), fungi are a major component of biodiversities, essential for the survival of other organisms and are crucial in global ecological processes. Fungi being ubiquitous organisms, occur in all types of habitats and are the most adaptable organisms. The soil is one of the most important habitats for microorganisms like bacteria, fungi, yeasts, nematodes, etc. The filamentous fungi are the major contributors to soil biomass (Alexander, 1977). They form the major group of organotrophic organisms responsible for the decomposition of organic compounds. Their activity participates in the biodeterioration and biodegradation of toxic substances in the soil (Rangaswami and Bagyaraj, 1998). It has been found that more number of genera and species of fungi exist in soil than in any other environment (Nagmani et al., 2005). Contributing to the nutrient cycle and the maintenance of ecosystem fungi play an important role in soil formation, soil fertility, soil structure and soil improvement (Pan et al., 2008). Fungi take a very important position in structure and function of ecosystem. They decompose organic matter from humus, nutrients, assimilate soil carbon and fix organic nutrients. An intense study of the abundance and diversity of soil microorganisms can divulge their role in nutrient recycling in ecosystem. Studies on the soil mycoflora in chilli field of Thiruvarur district and biological control of 1 Pythium debaryanum Hesse 1.1 Biological control of Pythium debaryanum in Chilli pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Systematic Position Class - Dicotyledons Order - Solanales Family - Solanaceae Genus - Capsicum Species - annuum Capsicum (Capsicum annuum L.) is an important spices crop extensively cultivated throughout the tropics and Southern countries such as Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. -

Download Download

The Journal of Threatened Taxa (JoTT) is dedicated to building evidence for conservaton globally by publishing peer-reviewed artcles OPEN ACCESS online every month at a reasonably rapid rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org. All artcles published in JoTT are registered under Creatve Commons Atributon 4.0 Internatonal License unless otherwise mentoned. JoTT allows unrestricted use, reproducton, and distributon of artcles in any medium by providing adequate credit to the author(s) and the source of publicaton. Journal of Threatened Taxa Building evidence for conservaton globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Communication Vaduvur and Sitheri lakes, Tamil Nadu, India: conservation and management perspective V. Gokula & P. Ananth Raj 26 May 2021 | Vol. 13 | No. 6 | Pages: 18497–18507 DOI: 10.11609/jot.5547.13.6.18497-18507 For Focus, Scope, Aims, and Policies, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/aims_scope For Artcle Submission Guidelines, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/submissions For Policies against Scientfc Misconduct, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/policies_various For reprints, contact <[email protected]> The opinions expressed by the authors do not refect the views of the Journal of Threatened Taxa, Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society, Zoo Outreach Organizaton, or any of the partners. The journal, the publisher, the host, and the part- Publisher & Host ners are not responsible for the accuracy of the politcal boundaries shown in the maps by the authors. Member Threatened Taxa Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 May 2021 | 13(6): 18497–18507 ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) OPEN ACCESS htps://doi.org/10.11609/jot.5547.13.6.18497-18507 #5547 | Received 11 November 2019 | Final received 17 April 2021 | Finally accepted 05 May 2021 COMMUNICATION Vaduvur and Sitheri lakes, Tamil Nadu, India: conservaton and management perspectve V. -

Tamil Nadu Industrial Connectivity Project: Thanjavur to Mannargudi

Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Draft January 2021 IND: Tamil Nadu Industrial Connectivity Project Thanjavur to Mannargudi (SH63) Prepared by Project Implementation Unit (PIU), Chennai Kanyakumari Industrial Corridor, Highways Department, Government of Tamil Nadu for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 7 January 2021) Currency unit – Indian rupee/s (₹) ₹1.00 = $0. 01367 $1.00 = ₹73.1347 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AH – Affected Household AP – Affected Person BPL – Below Poverty Line CKICP – Chennai Kanyakumari Industrial Corridor Project DC – District Collector DE – Divisional Engineer (Highways) DH – Displaced Household DP – Displaced Person DRO – District Revenue Officer (Competent Authority for Land Acquisition) GOI – Government of India GRC – Grievance Redressal Committee IAY – Indira Awaas Yojana LA – Land Acquisition LARRU – Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Unit LARRIC – Land Acquisition Rehabilitation and Resettlement Implementation Consultant PD – Project Director PIU – Project implementation Unit PRoW – Proposed Right-of-Way RFCTLARR – The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 R&R – Rehabilitation and Resettlement RF – Resettlement Framework RSO – Resettlement Officer RoW – Right-of-Way RP – Resettlement Plan SC – Scheduled Caste SH – State Highway SPS – Safeguard Policy Statement SoR – Schedule of Rate ST – Scheduled Tribe NOTE (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of India ends on 31 March. FY before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2021 ends on 31 March 2021. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This draft resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

List of Public Information Officers of Various Department Under Rti Act of Thiruvarur District

LIST OF PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICERS OF VARIOUS DEPARTMENT UNDER RTI ACT OF THIRUVARUR DISTRICT. Sl. Department / Public Telephone / Appellate Telephone / Fax No. Office Name Information Fax Authority Officers 1 District Collector Personal Assistant 04366 District Revenue STD - 04366 Office, Thiruvarur. (General) to 220889 Officer, Office 220 483 Collector, Thiruvarur. House 224 178 Thiruvarur. Fax : 221 033 District Adi 04366 District Revenue 04366 – 220 483 Dravider and 220528 Officer, Tribal Welfare Thiruvarur. Officer, Thiruvarur. District Backward 04366 – 220 District Revenue 04366 – 220 483 Classes and 519 Officer, Mionrity Welfare Thiruvarur. Officer, Thiruvarur. District Supply 04366 -220 District Revenue 04366 – 220 483 and Consumer 510 Officer, Protection Officer, Thiruvarur. Thiruvarur. Assistant 04366 – District Revenue 04366 – 220 483 Commissioner 220 501 Officer, (Excise), Thiruvarur. Thiruvarur. Special Deputy 04366 District Revenue 04366 – 220 483 Collector ( Social 225662 Officer, Security Scheme) Thiruvarur. Thiruvarur. Personal Assistant 04366 District Revenue 04366 – 220 483 (Accounts) to 251926 Officer, Collector, Thiruvarur. Thiruvarur. 2 Revenue Divisional Personal Assistant 04366 Revenue 04366 Office, Thiruvarur. to Revenue 240 537 Divisional Officer, 240 537 Divisional Officer. Thiruvarur. 3 Revenue Divisional Personal Assistant 04367 – Revenue 04367 – Office, Mannargudi. to Revenue 240 537 Divisional Officer, 252 261 Divisional Officer, Mannargudi. 4 Taluk Office, Head Quarters 04366 Tahsildar, 04366 Thiruvarur. Deputy Tahsildar. 222 379 Thiruvarur. 222 379 5 Taluk Office, Head Quarters 04366 Tahsildar, 04366 Nannilam. Deputy Tahsildar. 230 456 Nannilam. 230 456 6 Taluk Office, Head Quarters 04366 Tahsildar, 04366 Kudavasal. Deputy Tahsildar. 262056 Kudavasal. 262056 7 Taluk Office, Head Quarters 04374 Tahsildar, 04374 Valangaiman. Deputy Tahsildar. 264 456 Valangaiman. 264 456 8 Taluk Office, Head Quarters 04367 Tahsildar, 04367 Mannargudi. -

![316] CHENNAI, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2011 Aavani 22, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2042](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9055/316-chennai-thursday-september-8-2011-aavani-22-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2042-4179055.webp)

316] CHENNAI, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2011 Aavani 22, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2042

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2009-11. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2011 [Price: Rs. 140.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 316] CHENNAI, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2011 Aavani 22, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2042 Part II—Section 2 Notifications or Orders of interest to a section of the public issued by Secretariat Departments. NOTIFICATIONS BY GOVERNMENT RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND PANCHAYAT RAJ DEPARTMENT RESERVATION OF OFFICES OF CHAIRPERSONS OF PANCHAYAT UNION COUNCILS FOR THE PERSONS BELONGING TO SCHEDULED CASTES / SCHEDULED TRIBES AND FOR WOMEN UNDER THE TAMIL NADU PANCHAYAT ACT [G.O. Ms. No. 56, Rural Development and Panchayat Raj (PR-1) 8th September 2011 ÝõE 22, F¼õœÀõ˜ ݇´ 2042.] No. II(2)/RDPR/396(e-1)/2011. Under Section 57 of the Tamil Nadu Panchayat Act, 1994 (Tamil Nadu Act 21 of 1994) the Governor of Tamil Nadu hereby reserves the offices of the Chairpersons of Panchayat Union Council for the persons belonging to Scheduled Castes / Scheduled Tribs and for Women as indicated below: The Chairpersons of the Panchayat Union Councils. DTP—II-2 Ex. (316)—1 [ 1 ] 2 TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY RESERVATION OF SEATS OF CHAIRPERSONS OF PANCHAYAT UNION Sl. Panchayat Union Category to Sl. Panchayat Union Category to which No which Reservation No Reservation is is made made 1.Kancheepuram District 4.Villupuram District 1. Thiruporur SC (Women) 1 Kalrayan Hills ST (General) 2. Acharapakkam SC (Women) 2 Kandamangalam SC(Women) 3. Uthiramerur SC (General) 3 Merkanam SC(Women) 4. Sriperumbudur SC(General) 4 Ulundurpet SC(General) 5. -

2005- Journal 12Th Issue

JOURNAL OF INDIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE September 2005 Twelfth Issue C.P. RAMASWAMI AIYAR INSTITUTE OF INDOLOGICAL RESEARCH The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1, Eldams Road, Alwarpet, Chennai 600 018, INDIA EDITOR Dr. G.J. Sudhakar EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. K.V.Raman Dr. T.K.Venkatasubramaniam Dr. R.Nagaswami Dr. Nanditha Krishna Published by C.P.Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1, Eldams Road, Alwarpet, Chennai 600 018 Tel: 2434 1778 Fax: 91-44-24351022 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.cprfoundation.org Subscription Rs.95/- (for 2 issues) Rs.180/- (for 4 issues) CONTENTS Mahisha, The Buffalo Demon .................................................................... 7 Dr. Nanditha Krishna A Study of the Ramayana and Mahabharata .......................................... 11 Dr. S. Kuppusamy Secular and Religious Contribution of Performing Arts............................ 16 Dr. Prof. Mrs. V. Balambal Historiography of Professor K.A. Nilakanta Sastri ................................... 36 Dr. Shankar Goyal Female Functionaries of Medieval South Indian Temples........................ 51 Dr. S. Chandni Bi Society and Land Relation in the Kaveri Delta During the Chola Period A.d. 850–1300 ................................................................... 70 Mr. V. Palanichamy Note on Dutch Documents on Coastal Karnataka 1583–1763 .................. 81 Dr. K.G. Vasantha Madhava India Under the East India Company and the Transition to British Rule ... 85 Dr. Rukmini Nagarajan Kudikaval System in Madurai District ....................................................101 Dr. K.V. Jeyaraj and Mr. P. Jeganathan Articles of Trade, The System of Weights and Measures in Parlakhemundi Under the British Raj (A.d. 1858–1936): A Case Study of the Gajapati District.....................................................108 Dr. N.P. Panigrahi Indian Nationalism: Role of Cuddapah District in the Constructive Activities (1922–30) – A Micro Study ................................116 Dr. -

Tneb Limited Tangedco Tantransco Bulletin

TNEB LIMITED TANGEDCO TANTRANSCO BULLETIN AUGUST – 2018 CONTENTS Page No 1. PART – I NEWS & NOTES … … … 2 2. PART – II GENERAL ADMINISTRATIVE & SERVICES … … … 10 3. PART – III FINANCE … … … 2 4. PART – IV TECHNICAL … … … 3 5. INDEX … … … 6 NEWS & NOTES PART – I I. GENERATION/RELIEF PARTICULARS:- The Generation/Relief particulars for the month of August 2018 were as follows : Sl.No Particulars In Million Units I. TNEB GENERATION (Gross) Hydro 883.084 Thermal 1613.444 Gas 164.784 Wind 1.400 TNEB TOTAL 2662.712 II. NETT PURCHASES FROM CGS 1589.113 III. PURCHASES IPP 190.885 Windmill Private 2862.693 CPP, Co- generation & Bio-Mass (Provisional) 35.800 Solar (Private) 278.506 Through Traders (nett purchase) 1693.357 TOTAL PURCHASES 5061.241 IV. Total Wheeling Quantum by HT consumers 642.255 Total Wheeling Quantum to Other States by Pvt. Generators 16.840 Total TNEB Power generation for sale 0.132 TOTAL WHEELING 659.095 Power Sale by TANGEDCO (Exchange) (-)0.132 Power Sale by TANGEDCO (STOA under Bilateral) 0.000 Power Sale by Private Generators (Exchange) (-)14.432 Power Sale by Private Generators (Bilateral) (-)2.408 Power balance under SWAP (-)378.406 V. TOTAL (TNEB Own Gen + Purchase + wheeling quantum + SWAP) 9576.915 VI. Load shedding & Power cut relief (Approx) 0 VII. Less energy used for Kadamparai pump 0.000 Less Aux. consumption for Hydro, Thermal & Gas 138.707 VIII. AVERAGE PER DAY REQUIREMENT 309 IX. DETAILS OF NETT PURCHASES FROM CGS & OTHER REGIONS: Neyveli TS-I 150.738 Neyveli TS-I Expansion 36.535 Neyveli TS-II Expansion 39.850 -

District Survey Report of Thiruvarur District

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF THIRUVARUR DISTRICT DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINING THIRUVARUR DISTRICT 1 DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT- THIRUVARUR CONTENTS S.No Chapter Page No. 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 Overview of Mining Activity in the District; 4 3.0 General profile of the district 4 4.0 Geology of the district; 9 5.0 Drainage of irrigation pattern 10 6.0 Land utilisation pattern in the district; Forest, Agricultural, 10 Horticultural, Mining etc 7.0 Surface water and ground water scenario of the district 11 8.0 Rainfall of the district and climate condition 11 9.0 Savudu/Earth - Details of the mining lease in the district as per 13 following format 10.0 Details of Royalty / Revenue received in the last three years 17 (2015-16 to 2017-18) 11.0 Details of Production of Minor Mineral in last three Years 26 12.0 Mineral map of the district 26 13.0 List of letter of intent (LOI) holder in the district along with its 27 validity 14.0 Total mineral reserve available in the district. 28 15.0 Quality / Grade of mineral available in the district 28 16.0 Use of mineral 29 17.0 Demand and supply of the mineral in the lase three years 30 2 DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT- THIRUVARUR 18.0 Mining leases marked on the map of the district 31 19.0 Details of the area where there is a cluster of mining leases viz., 33 number of mining leases, location (latitude & longitude) 20.0 Details of eco-sensitive area 33 21.0 Impact on the environment due to mining activity 35 22.0 Remedial measure to mitigate the impact of mining on the 36 environment 23.0 Reclamation of mined out