Production Design: Architects of the Screen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Joseph Losey

Joseph Losey Cinéma Institut de l’image 21 octobre – 3 novembre 2009 Le Garçon La Bête s’éveille Les Criminels aux cheveux verts The Sleeping Tiger (GB, 1954) 89 min The Criminal / The Concrete Jungle (GB, 1960) 97 min The Boy with Green Hair (USA, 1948) 82 min Joseph Scén. Harold Buchman, Carl Foreman, À partir de 10 ans d’après Maurice Moisiewitsch Scén. Alan Owen, d’après un sujet de Losey Scén. Ben Barzman, Alfred Lewis Levitt Int. Dirk Bogarde, Alexis Smith, Alexander Jimmy Sangster Int. Pat O’Brien, Robert Ryan, Barbara Int. Stanley Baker, Sam Wanamaker, 21 octobre – Knox, Maxine Audley… Grégoire Aslan… 3 novembre 2009 Hale, Dean Stockwell… Un psychiatre installe chez lui un jeune « Cinéaste cosmique (…), Losey Peter, séparé de ses parents par la voyou dont il veut faire un sujet d’expé- Johnny a passé ses trois dernières années de prison à mettre au point le peut être aussi claustrophobique guerre, est recueilli par Gramp, un rience… vieil acteur irlandais chaleureux. Un plus gros vol de sa carrière. À sa sortie, (…). Analyste subtil des gouffres matin, les cheveux de Peter devien- Dirigé par Losey, exilé en Grande-Bre- il met son plan à exécution. Il cache du psychisme et de l’ambiguïté nent subitement verts. Très vite, il sent tagne pour fuir le mccarthysme, sous l’argent, mais il est arrêté avant d’avoir humaine, peintre sans complai- peser sur lui le regard des autres… le pseudonyme de Victor Hanbury, pu informer ses complices. Ceux-ci sance d’une société vouée au La Bête s’éveille, film à l’ambiance s’empressent de le sortir de prison… matérialisme et du pouvoir destruc- Le premier film de Losey. -

Vintage Violence La Strana Violenza Del Cinema Di Losey Tarcisio Lancioni

Article Vintage Violence. La strana violenza del cinema di Losey LANCIONI, Tarcisio Reference LANCIONI, Tarcisio. Vintage Violence. La strana violenza del cinema di Losey. EU-topias, 2015, vol. 9, p. 95-109 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:133780 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 DOSSIER: Vintage Violence 95 Vintage Violence La strana violenza del cinema di Losey Tarcisio Lancioni Ricevuto: 15.09.2014 – Accettato: 16.01.2015 Sommario / Resumen / Résumé / Abstract sion («lacération» / «contrainte») face un seuil «conventionnel». Cette hypo- thèse est développée dans l’analyse des films de Joseph Losey dans lesquels Poiché i testi sulla violenza tendono a non interrogarsi sul senso di questo la violence apparaît sous différentes formes sans pourtant jamais devenir concetto, l’articolo prova a delinearne una definizione attraverso la lettura totalement explicite ou spectaculaire. L’article reprend l’analyse de Gilles di qualche classico e di voci dizionariali, per proporre una caratterizzazione Deleuze dans L’image-Mouvement, où il montre comment la violence de Losey della violenza come dispositivo semiotico, di ordine figurale, che articola due est principalement inscrite au corps de l’acteur et au pouvoir de ce dernier diverse figure di aggressione («lacerazione»/«costrizione») contro una soglia de vibrer sous l’influence des pulsions. Mais dans le cinéma de Losey nous «convenzionale». Questa ipotesi viene sviluppata analizzando i film di Losey, pouvons aussi y retrouver d’autres expressions de violence et cet article in cui la violenza appare sotto molteplici forme, pur senza mostrarsi come cherche justement à les comprendre selon le dispositif proposé. -

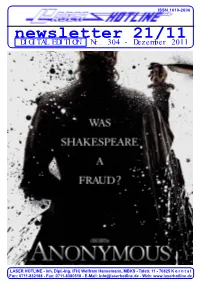

Newsletter 21/11 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 21/11 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 304 - Dezember 2011 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 21/11 (Nr. 304) Dezember 2011 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, sofern freuen wir uns auf jeden Fall und Blu-ray Disc in den Handel liebe Filmfreunde! auf das kommende Jahr, das in die- bringen. Beide Medien werden die ser Hinsicht ganz sicher eine Ent- Freigabe “keine Jugendfreigabe” Jetzt ist es also soweit: dies ist un- scheidung bringen wird. aufweisen, dürfen also nur an Per- ser letzter Newsletter im Jahre sonen ab 18 Jahren verkauft wer- 2011. Und glaubt man dem Kalen- Eine Entscheidung, die noch in die- den. Sobald die genauen Termine der der sehr weisen Maya-Kultur, sem Jahr gefallen ist, betrifft Tobe und Preis feststehen, finden Sie den dann könnte das sogar der letzte Hoopers Kultfilm THE TEXAS Titel natürlich automatisch in unse- Newsletter überhaupt sein. Denn CHAINSAW MASSACRE, der in rer Übersicht im Newsletter. Und laut den Mayas gibt es 2012 den Deutschland unter dem Titel damit hätten wir noch einen weite- ganz großen Knall. Und mal ganz BLUTGERICHT IN TEXAS zu ren Grund, dem verstaubten Maya- ehrlich: haben Sie nicht auch sehen war. 26 Jahre lang war die- Kalender zu misstrauen. Wäre dich manchmal das Gefühl, dass das ser Meilenstein des modernen Hor- jammerschade wenn ausgerechnet stimmen könnte? Angesichts welt- rorfilms auf der Beschlagnahme- dann die Welt untergeht, wenn wir weiter Finanzkrisen und Umwelt- liste der Bundesrepublik Deutsch- endlich Tobe Hoopers Filmperle katastrophen ist es ja absolut kein land. -

A Carnivalesque Analysis of the Monster Child from Early Slapstick to the Nazified Children of Modern Horror

BEWARE! CHILDREN AT PLAY: A CARNIVALESQUE ANALYSIS OF THE MONSTER CHILD FROM EARLY SLAPSTICK TO THE NAZIFIED CHILDREN OF MODERN HORROR Submitted by Craig Alan Frederick Martin, BA (Hons), MA https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8596-6482 A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2020 Faculty of Arts, School of Culture and Communication, Screen and Cultural Studies Program The University of Melbourne Abstract Monster child narratives often use a formula in which normative power relations between adults and children are temporarily inverted as the child outsmarts the adult, leading to a rupture in the social order. Where children are ordinarily subordinate to adults, this relationship is reversed as the monster child exerts dominance over their elders. Applying Mikhail Bakhtin’s carnival theory, this thesis argues that the monster child figure commonly thought of as a horror movie villain began its life on screen in early silent screen comedy. Through qualitative analysis of a range of case study films from the silent era through to the emergence of horror-themed monster child films produced in the mid- 1950s, close comparative analysis of these texts is used to support the claim that the monster children in early silent comedies and later modern horror films have a shared heritage. Such a claim warrants the question, why did the monster child migrate from comedy to horror? The contention put forward in this thesis is that during World War II dark representations of Hitler Youth in Hollywood wartime propaganda films played a significant role in the child monster trope moving from comedy to horror. -

National Gallery of Art 2009 Film Program Enters Fall Season with Dynamic Line-Up Including D.C

Office of Press and Public Information Fourth Street and Constitution Av enue NW Washington, DC Phone: 202-842-6353 Fax: 202-789-3044 www.nga.gov/press Release Date: September 2, 2009 National Gallery of Art 2009 Film Program Enters Fall Season With Dynamic Line-Up Including D.C. Film Premieres and Guest Speakers Film still f rom The Korean Wedding Chest (Die Koreanische Hochzeitstruhe) (Ulrike Ottinger, 2008, 35 mm, Korean, English, and German with subtitles, 82 minutes) Image courtesy of the artist. This fall, the National Gallery of Art's film program provides a great variety of work, including area premieres combined with musical performances and appearances by noted film directors, as well as vibrant film series devoted to postwar "British noir" and the American expatriate director Joseph Losey, whose centennial is celebrated this year. Among the film events, on October 4, director Ulrike Ottinger will appear at the Washington premiere of The Korean Wedding Chest to discuss her film about the elegant, ancient tradition of the Korean wedding rite. On October 31, Catia Ott will introduce her film Tevere (Tiber), a cinematic exploration of Rome's famous river that reveals relics, surprises, and obscure spots that have inspired generations of artists. Eight recent works will be shown as part of the National Gallery's film series New Films From Hungary: Selections from Magyar Filmszemle, including the October 10 Washington premiere of White Palms—a feature film directed by Szabolcs Hajdu, inspired by his younger brother's life as a gymnast. Iván Angelusz, a founding member of Katapult Film Ltd., along with artists Ferenc Török and Diana Groó will speak about this dynamic collective of filmmakers and the cinematic talent emerging from Hungary today. -

Joseph Losey À Cannes Gene D

Document generated on 09/24/2021 4:32 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Joseph Losey à Cannes Gene D. Phillips Le cinéma canadien I Number 50, October 1967 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/51700ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Phillips, G. D. (1967). Joseph Losey à Cannes. Séquences, (50), 47–51. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 1967 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Gene D. Phillips Au cours du Festival de Cannes rackux, est plus représentatif de où Joseph Losey remporta le prix l'orientation de son oeuvre pos spéckl du jury pour son film Ac térieure. cident, j'ai eu l'occasion de discu En 1954, il se rendit en Angle ter de son oeuvre avec lui. terre en quête d'une liberté artis Né au Wisconsin, Losey a réa tique plus grande que celle qui lui lisé son premier film de long mé était permise à Hollywood. Depruis, trage, The Boy with Green Hair, Losey a dirigé quelques-unes des à Hollywood, en 1948. -

The Boy with Green Hair

The Boy With Green Hair US : 1948 : dir. Joseph Losey : RKO : 82 min prod: Stephen Ames : scr: Ben Barzman & Alfred Lewis Levitt : dir.ph.: George Barnes Dean Stockwell; Richard Lyon; Dwayne Hickman; Johnny Calkins; Teddy Infuhr; Bill Sheffield; Rusty Tamblyn ………….………………………………………………………….…………………… Pat O’Brien; Barbara Hale; Robert Ryan; Walter Catlett; Samuel S Hinds; Regis Toomey; Dale Robertson; Russ Tamblyn Ref: Pages Sources Stills Words Ω 8 M Copy on VHS Last Viewed 6070 7.5 17 15 3,146 No Mar 2003 Hollywood’s Cupid deluxe goes punk – and delivers a so-so performance in a clumsily-written homily with the central message “War is Bad for Children”. Well duhhh… More interesting is the theme of individuality vs conformity, especially given that children approaching puberty have an acute need for acceptance by their peer group. Peter could be black of course, or Jewish, but he could also be a boy dancer, a homosexual, an atheist or simply a kid with a heightened political awareness. In either case he’s a mutant, does not belong, and we’re still busy rooting him out from our midst, are we not? Source: Classic Movie Kids website Source: Classic Movie Kids website Leonard Maltin’s Movie and Video Guide 2001 review: Halliwell’s Film Guide review: “Thought provoking allegory of war orphan “When he hears that his parents were killed in Stockwell, who becomes a social outcast when an air raid, a boy’s hair turns green; other war his hair changes colour. Controversial on its orphans encourage him to parade himself release because of its pacifist point of view. -

La Violenza Sottile Del Cinema Di Losey Tarcisio Lancioni

La violenza sottile del cinema di Losey Tarcisio Lancioni “nulla di decisivo può essere pensato al di fuori della violenza” É. Balibar 1. Della violenza Cos’è la violenza? da che cosa la riconosciamo? quand’è che qualcosa ci appare violento? o meglio, quand’è che qualcosa ci significa “violenza”? La letteratura semiotica non ci offre grande aiuto, e benché non manchino studi e lavori su “cose” che classificheremmo senza esitazione violente, come guerre, delitti o torture, non sono riuscito a trovare qualche testo che cerchi specificamente di definire “la violenza”. D’altra parte anche la letteratura classica sul tema, dal Walter Benjamin critico di Sorel ad Hannah Arendt, o da Pierre Clastres a René Girard, sembra assumere la violenza come qualcosa di scontato: vi si discute della legittimità del suo uso, del ruolo della violenza nel formarsi delle società primitive e del suo valore fondativo, ma non si tenta di dire in cosa essa consista né da cosa effettivamente riconosciamo “la violenza”. Per trovare una via di accesso al problema proviamo perciò a rivolgerci al dizionario, luogo istituzionale della memoria semantica della lingua: «violenza. s.f. 1 Forza impetuosa e incontrollata; estens.: la v. del temporale. 2 Azione volontaria, esercitata da un soggetto su un altro, in modo da determinarlo ad agire contro la sua volontà. Violenza assoluta (o violenza materiale), se la resistenza del soggetto è totale. Violenza morale, se è relativa e basata sul timore di chi la subisce. Violenza fisica, se attuata come costrizione materiale. Violenza carnale, il reato di chi impone ad altri con la forza un rapporto sessuale. -

DOUBLE PLAY Author(S): RICHARD COMBS Source: Film Comment, Vol

DOUBLE PLAY Author(s): RICHARD COMBS Source: Film Comment, Vol. 40, No. 2 (MARCH/APRIL 2004), pp. 44-49 Published by: Film Society of Lincoln Center Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43456680 Accessed: 15-04-2020 08:52 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Film Society of Lincoln Center is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Film Comment This content downloaded from 95.183.180.42 on Wed, 15 Apr 2020 08:52:50 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms ÜÜUiJLS 44 This content downloaded from 95.183.180.42 on Wed, 15 Apr 2020 08:52:50 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms LAY CONTINUALLY REINVENTING HIS CAREER AND ELUDING ALL CATEGORIZATION, JOSEPH LOSEY DEFIED THE AXIOM THAT THERE ARE NO SECOND ACTS. BY RICHARD COMBS "To each his own Losey" is how The Servant the and King and Country (64), critic Tom Milne began his 1967 just inter-prior to Accident . One could even aigue view book with Joseph Losey. that,His intally terms of stylistic attack, Losey's of Loseys at that point was three: last the American Hol- film is not The Big Night lywood version (1948-52), the (51), early barely finished before he fled the British incarnation (1954-62), andcountry the and the blacklist, but The Damned art-house auteur revealed in The (a.k.a.Servant These Are the Damned) (62), which (63) and culminating in Accident is also (67).his seventh British film. -

Noviembre 2017

noviembre 2017 Universo Zombi 8.ª Muestra de Cine Rumano Ciclo de Cine Eslovaco Mi Primer Festival [Filmoteca Junior] Joseph Losey: el americano errante (II) El ojo en la materia. Dziga Vertov y el cine soviético temprano (II) Adam Curtis, Mariano Llinás, Ana Mendieta... 1 miércoles 2 jueves 3 viernes 4 sábado 5 domingo No hay sesiones 17:30 - Sala 1 • Juego de espejos / Universo Zombi 17:30 - Sala 1 • El ojo en la materia 17:30 - Sala 1 • Filmoteca Junior / Recuerdo Jean 17:30 - Sala 1 • Universo Zombi Rochefort Casa de Lava (Pedro Costa, 1994). Int.: Inês El gran camino (Velikii put’, Esfir Shub, Yo anduve con un zombi (I Walked with de Medeiros, Isaach De Bankolé, Edith Scob, Pe- 1927). URSS. 35 mm. MRR/E*. 115’ Astérix y Obélix: al servicio de Su a Zombie, Jacques Tourneur, 1943). Int.: James dro Hestnes, Cristina Andrade Alves. Portugal, «El atento ojo de Shub se caracteriza por sus largas Majestad (Astérix & Obélix: Au service de Ellison, Frances Dee, Tom Conway, Edith Ba- Francia, Alemania. DCP. VOSE. 110’ tomas y su reflexión visual. (…) Este excedente de sa Majesté, Laurent Tirard, 2012) Int.: Gerard rrett, James Bell. EEUU. 35 mm. VOSE. 69’ «La película es una reinterpretación libre de Yo andu- percepción genera inquietud y curiosidad en el es- Depardieu, Edouard Baer, Fabrice Lucini, Jean ve con un zombi, de Jacques Tourneur, en la que los pectador, cuyo ojo analiza la imagen en busca de Rochefort. España, Francia, Hungría, Italia. 20:00 - Sala 2 • El ojo en la materia zombis y los fantasmas, tan presentes desde entonces alguna dosis adicional de contenido que pueda justi- B-R. -

National Gallery of Art Fall 09 Film Program U.S

Non-Profit Org. NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART FALL 09 FILM PROGRAM U.S. Postage Paid Washington DC 4th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, DC Mailing address 2000B South Club Drive, Landover, MD 20785 Permit # 9712 New Films from Hungary: Recovered Selections Joseph Losey: Treasure: from Magyar The Silesian American UCLA’S Festival Filmszemle Trilogy Brit Noir Abroad OF Preservation The Criminal the Door Urlicht Point of Order cover calendar page page four page three page two page one (Magyar Filmunió) The Servant ( UCLA The Crowd The October Man The Brother from Another Planet (British Film Institute), Sleeping Tiger details from FALL09 ( and Photofest), UCLA (Photofest) and Photofest), (Photofest) (Photofest) The Servant (Photofest) Night and the City Tevere Brighton Rock (Photofest), ( (Catia Ott), IFC Films) (Photofest), Secret Beyond (Rialto Pictures), M (Photofest), Lecture / Screening: American Visionary Filmmakers and the Heritage of Emerson Illustrated discussion by P. Adams Sitney Sunday December 6 at 2:00 Film Events Distinguished film historian, theorist, and professor of visual arts at Princeton University, P. Adams Sitney discusses American avant-garde cinema as fulfill- New Masters of European Cinema: ment of the promise of an American aesthetic, an idea first defined by Ralph The Korean Wedding Chest (Die Koreanische Hochzeitstruhe) Waldo Emerson. Four films follow his lecture:Arabesque for Kenneth Anger Ulrike Ottinger in person (Marie Menken); Visions in Meditation #2 — Mesa Verde (Stan Brakhage); Gloria Washington premiere (Hollis Frampton); and Gently Down the Stream (Su Friedrich). (Approximate Sunday October 4 at 4:30 total running time, 120 minutes) This program is made possible by funds given in memory of Rajiv Vaidya.