Myplace Evaluation – Final Report Durham University YMCA George Williams College | April 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

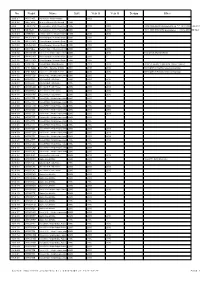

No. Regist Name Built Year O Year O Scrapp Other

No. Regist Name Built Year O Year O Scrapp Other 20527 WV 53 KTL Volvo B12M / Plaxton Paragon ? 2002 51556 M857 XHY Mercedes-Benz 811 D / Marshall 1994 ? 655 TOS 31YW Mercedes-Benz 609 D / Frank Guy 1995 2000 2008 24.08.1995 N613 GAH pierwsza rej. 28.02.2008 TOS 31YW 31.01.2018 zgłoszenie sprzedaży 52574 SBI 56J4 Mercedes-Benz 814 D / Plaxton Beaver1998 2 ? 2010 10.11.1998 S864 LRU pierwsza rej. 30.12.2010 SBI 56J4 32859 V859 HBY Dennis Trident 2 / Plaxton President 1999 2015 2016 34108 W435 CWX Volvo Olympian / Alexander Royale 2000 2000 ? 34110 W437 CWX Volvo Olympian / Alexander Royale 2000 2000 ? 34109 W436 CWX Volvo Olympian / Alexander Royale 2000 2000 ? 32947 W947 ULL Dennis Trident 2 / Alexander ALX400 2000 2014 2016 10036 W119 CWR Volvo B7LA / Wright Eclipse Fusion 2000 ? 2016 First Leeds (Hunslet Park) 34114 W434 CWX Volvo Olympian / Alexander Royale 2000 2000 ? 34112 W432 CWX Volvo Olympian / Alexander Royale 2000 2000 ? 62245 Y938 CSF Volvo B10BLE / Wright Renown 2001 2001 2018 2018 > Leicester CityBus Ltd. (Driver Trainer) 32075 KP51 WAO Volvo B7TL / Alexander ALX400 2001 2015 2016 08.10.2015 > First Somerset & Avon Ltd. 32076 KP51 WAU Volvo B7TL / Alexander ALX400 2001 2015 2016 08.10.2015 > First Somerset & Avon Ltd. 66952 WX55 TZO Volvo B7RLE / Wright Eclipse Urban 2005 2005 42898 WX05 RVC ADL Dart SLF / ADL Pointer 2005 2005 2016 42903 WX05 RVL ADL Dart SLF / ADL Pointer 2005 2005 2016 42557 WX05 UAO ADL Dart SLF / ADL Pointer 2005 2005 2015 42906 WX05 RVO ADL Dart SLF / ADL Pointer 2005 2005 2016 42916 WX05 RWF ADL Dart -

The Leicestershire Historian

the Leicestershire Historian 1975 40p ERRATA The Book Reviews should be read in the order of pages 32, 34, 33, & 35. THE LEICESTERSHIRE HISTORIAN Vol 2 No 6 CONTENTS Page Editorial 3 Richard Weston and the First Leicester Directory 5 J D Bennett Loughborough's First School Board Election 10 31 March 1875 B Elliott Some Recollections of Belvoir Street, 15 Leicester, in 1865 H Hackett Bauthumley the Ranter 18 E Welch The Day of the Year - November 14th 1902 25 C S Dean Chartists in Loughborough 27 P A Smith Book Reviews 32 Mrs G K Long, J Goodacre The Leicestershire Historian, which is published annually is the magazine of the Leicestershire Local History Council, and is distributed free to members. The Council exists to bring local history to the doorstep of all interested people in Leicester and Leicestershire, to provide for them opportunities of meeting together, to act as a co-ordinating body between the various Societies in the County and to promote the advancement of local history studies. A series of local history meetings is arranged throughout the year and the programme is varied to include talks, film meetings, outdoor excursions and an annual Members' Evening held near Christmas. The Council also encourages and supports local history exhibitions; a leaflet giving advice on the promotion of such an exhibition is available from the Secretary. The different categories of membership and the subscriptions are set out below. If you wish to become a member, please contact the Secretary, who will also be pleased to supply further information about membership and the Annual Programme. -

Leicester Environment City: Learning How to Make Local Agenda 21, Partnerships and Participation Deliver

Leicester environment city: learning how to make Local Agenda 21, partnerships and participation deliver Ian Roberts Ian Roberts is Director of SUMMARY: This paper describes the pioneering experience of the city of Leices- Environ Sustainability. The ter (in the UK) over the last 10 years in developing its Local Agenda 21, and other early part of his career was spent in the private sector aspects of its work towards environmental improvement and sustainable develop- working in the oil industry ment. It includes details of measures to improve public transport and to reduce and, following an MBA, as congestion, traffic accidents, car use and air pollution. It also describes measures to a management consultant. In the late 1980s, he acted improve housing quality for low-income households, to reduce fossil fuel use and as chief executive of an increase renewable energy use and to make the city council's own operations a investment company, at the model for reducing resource use and waste. It also describes how this was done – the time New Zealand’s specialist working groups that sought to make partnerships work (and their sixteenth largest company. In 1990, he was appointed strengths and limitations), the information programmes to win hearts and minds, director of Environment the many measures to encourage widespread participation (and the difficulties in City Trust with involving under-represented groups) and the measures to make local governments, responsibility for management of the businesses and other groups develop the ability and habit of responding to the local Leicester Environment City needs identified in participatory consultations. initiative. -

INSTITUTE of TRANSPORT and LOGISTICS STUDIES WORKING

WORKING PAPER ITLS-WP-19-05 Collaboration as a service (CaaS) to fully integrate public transportation – lessons from long distance travel to reimagine Mobility as a Service By Rico Merkert, James Bushell and Matthew Beck Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies (ITLS), The University of Sydney Business School, Australia March 2019 ISSN 1832-570X INSTITUTE of TRANSPORT and LOGISTICS STUDIES The Australian Key Centre in Transport and Logistics Management The University of Sydney Established under the Australian Research Council’s Key Centre Program. NUMBER: Working Paper ITLS-WP-19-05 TITLE: Collaboration as a service (CaaS) to fully integrate public transportation – lessons from long distance travel to reimagine Mobility as a Service Integrated mobility aims to improve multimodal integration to ABSTRACT: make public transport an attractive alternative to private transport. This paper critically reviews extant literature and current public transport governance frameworks of both macro and micro transport operators. Our aim is to extent the concept of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS), a proposed coordination mechanism for public transport that in our view is yet to prove its commercial viability and general acceptance. Drawing from the airline experience, we propose that smart ticketing systems, providing Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) can be extended with governance and operational processes that enhance their ability to facilitate Collaboration-as-a-Service (CaaS) to offer a reimagined MaaS 2.0 = CaaS + SaaS. Rather than using the traditional MaaS broker, CaaS incorporates operators more fully and utilises their commercial self-interest to deliver commercially viable and attractive integrated public transport solutions to consumers. This would also facilitate more collaboration of private sector operators into public transport with potentially new opportunities for taxi/rideshare/bikeshare operators and cross geographical transport providers (i.e. -

Notices and Proceedings for West Midlands

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (WEST MIDLANDS) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2445 PUBLICATION DATE: 24/04/2020 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 15/05/2020 PLEASE NOTE THE PUBLIC COUNTER IS CLOSED AND TELEPHONE CALLS WILL NO LONGER BE TAKEN AT HILLCREST HOUSE UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE The Office of the Traffic Commissioner is currently running an adapted service as all staff are currently working from home in line with Government guidance on Coronavirus (COVID-19). Most correspondence from the Office of the Traffic Commissioner will now be sent to you by email. There will be a reduction and possible delays on correspondence sent by post. The best way to reach us at the moment is digitally. Please upload documents through your VOL user account or email us. There may be delays if you send correspondence to us by post. At the moment we cannot be reached by phone. If you wish to make an objection to an application it is recommended you send the details to [email protected]. If you have an urgent query related to dealing with coronavirus (COVID-19) response please email [email protected] with COVID-19 clearly stated in the subject line and a member of staff will contact you. If you are an existing operator without a VOL user account, and you would like one, please email [email protected] and a member of staff will contact you as soon as possible to arrange this. You will need to answer some security questions. Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West Midlands) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 24/04/2020 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. -

170 'Lao T.Rades. Cleioi8ter8e1ire

170 'LAO T.RADES. CLEIOI8TER8E1IRE LACE & LENO CURTAIN Flet1!her William Frederick (sub- eaton; (H. Chapman, mana~er) DRESSERS. agent to the Duke of Rutland), Bel- ~Iarkfield, Leice- ter; (G. H. Hip- Grantham well, mana,g~l') Measham, Leicester Calow Mrs. L. 2 Biddulph st. Leicstr voir, Clarke C. & A. 93 Dorothy rd. North Garratt Charles Thomas (to Mrs. & (J. J. St:.ltlhulll, manager) New- Evington, Leicester Katherine H. V. Grey), Newtown bold-de·Venlull, Le~ce.,t-eI Mason Mrs. Emma, 24 Edward road, Linford, Leice"ter Hincldf'Y Permamnt Building Society Clarendon park, Leicester Hamerley W. H. (to Mrs. Perry-Her- (1'. Kiddle, manageI'), 36a, Castle st. rick), 'Yoodhouse. Loughborough Hinckley; (GEO! ge .harry Hewes, Saunders Mrs. E. 21 Kate st. Leicestr Harvey Charles Stephen (to John branch manager), Lundon rd. Coal- LADDER MAKERS. Gretton esg. M.P.), Wymondham villI', Leicester; & (W. J. NOl'man~ Wain W. S. 40 Percival st. Leicester house, Wymondham, Oakham branch manJger), Cosby, Leicester Watts Bros. 75 Loughborough road, Hough John (to Sir G. H. 'Y. Beau- Hinckley & Suuth Lancashire Per- mont, bart.), Coleorton, Ashby-de- mallent Building .Society (William Belgrave, Leicester la-Zouch Pickering, Iranager), 17 Borough. LADIES' OUTFITTERS. Kin~ George (to the Earl of Dysart), Hincklt'y Spe also Outfitters-Ladies'. Buckminster, Grantham Lejce·~ter Lan{l Co. Ltd.; (James Little Robert (to Thomas Augustus Thomas, sec.); leg. office, Rowton Robinson & Clf'aver Ltd. (of Belfast), Hardcastle esg.), Horninghold, Up- bu~ldinqs, II Bowling Green street, 156 to 170 Regent street W; I to pingham ~PICester.. 13 Beak street W; 61 to 70 Kingly Nelson Hon. -

Cultural Exchanges Is Generously Dmu.Ac.Uk/Culturalexchanges Supported by Unite Students

27 FEB–3 MARCH FESTIVAL 2017 FEATURING: Wayne Hemingway Kanya King Nina Stibbe Martin Bell Box Office (0116) 250 6229 Cultural eXchanges is generously dmu.ac.uk/culturalexchanges supported by Unite Students LAUNCH PARTY JONATHAN MONK The Font THE SOUND OF LAUGHTER ISN’T WELCOME TO THE 16TH 52, Gateway Street, LE2 7DP NECESSARILY FUNNY Friday 24 February 6–9pm The Gallery, Vijay Patel Building Everyone is invited to the Launch Party for the Friday 27 January–Saturday 11 March 2017 Cultural eXchanges Festival 2017! This event Jonathan Monk is one of the world’s leading will see us joined by a host of guests to celebrate contemporary artists. His work has been the 16th year of our student-led festival. All are collected by The Tate, Guggenheim and Moderna welcome, please contact us to join the guestlist Museet, Stockholm. For his exhibition ‘The Sound and find out more on (0116) 250 6229. of Laughter Isn’t Necessarily Funny’, his first in Leicester, he has developed new works that look at our experience of time in different ways. FESTIVAL 2017 ARTS & HERITAGE ON CAMPUS DMU ART COLLECTIONS We are delighted to welcome a host of national and THE MONSTERS OF HAMMER international guests to the festival. These include the Explore DMU’s Art Collections on campus using DMU Heritage Centre renowned former BBC War correspondent, Martin Bell, our Art Trail leaflets available from Clephan November 2016–May 2017 celebrated designer Wayne Hemingway, best-selling Building, Vijay Patel Building and Kimberlin novelist Nina Stibbe and legendary USA investigative Terror! Horror! Blood! Famed for its gruesome Library receptions. -

Gender Pay Gap Report 2017 Introduction Our Headline Figures

Gender Pay Gap report 2017 Introduction Our headline figures Our median gender pay gap is -9.1% This means women’s median hourly pay is 9.1% higher than men’s. We are a leading transport operator in the UK and North America. “ FirstGroup is committed Our mean gender Each year, two billion passengers rely on us to get to work, school or to equality of opportunity, college, to visit family and friends and much more. pay gap is diversity and inclusion at -2.2% In our increasingly urban and global world, the transport links we provide are more essential than ever. every level, both in our Boardroom and across The unique scale and the breadth of FirstGroup’s global expertise is Explaining our results our key strength. But to truly capitalise on this, and provide the best our wider business. services for our customers, we recognise that the diversity between The number of UK employees covered by our report at 5 April We have made this and within all the communities we serve must be reflected in our 2017 is 22,236. workforce. commitment because We recognise that women have traditionally been under-represented we believe diverse This comprises 19,407 men and 2,829 women. in the UK transport sector, but as the industry evolves to meet rising experiences and Although only 13% of UK employees are female, more than customer expectations, and environmental challenges like congestion and air pollution, we need a much broader range of skills. This attitudes help us better 61% of these women are in the upper and upper middle pay transformation is creating many more opportunities for women with understand the needs quartiles, whereas 52% of men are in the lower and lower backgrounds outside the transport sector to bring a variety of skills of our customers and middle quartiles. -

The First Leicester Thesis in English Local History William Farrell 14 July 2017 Url

The first Leicester thesis in English Local History William Farrell 14 July 2017 Url: https://elhleics.omeka.net/firstthesis For the first blog post, it seemed appropriate to look at the first thesis in the collection L. A. Parker’s Enclosure in Leicestershire, 1485-1607 awarded in 1948. Leslie Arthur Parker (1917-2005) studied History at University College Leicester from 1936 to 1948. He was clearly a good student, winning the honours prize in 1938 and 1939. Like many current students, he lived around the Narborough Road area, first on Cambridge Street and then on Mavis Avenue. He registered for an MA in Economic History in 1939, but he was not awarded the second degree until 1946/47. His doctorate came the following year. This quick succession of awards is unusual - researching a PhD in a year seems impossible! Perhaps Parker was working on this research through the Second World War, even if he was not formally registered with the University. Parker's choice of subject suggests that W.G. Hoskins was his supervisor, although this is not recorded on the bibliographic record, or on the thesis itself. His topic - enclosure - was the process by which open fields were converted into pasture by landholders, and the common rights of villagers were eroded. It has long been seen as a key development in the agriculture and landscape of England. Hoskins was also working on the history of rural Leicestershire through the 1940s and 1950s, culminating in his famous study of Wigston Magna. Both cited each other’s work and Hoskins thanked Parker in the acknowledgements to The Midlands Peasant. -

Bus Operators in the British Isles

BUS OPERATORS IN THE BRITISH ISLES UPDATED 21/09/21 Please email any comments regarding this page to: [email protected] GREAT BRITAIN Please note that all details shown regarding timetables, maps or other publicity, refer only to PRINTED material and not to any other publications that an operator might be showing on its web site. A & M GROUP Uses Warwickshire CC publications Fleetname: Flexibus Unit 2, Churchlands Farm Industrial Estate, Bascote Road, Harbury CV33 9PL Tel: 01926 612487 Fax: 01926 614952 Email: [email protected] www.flexi-bus.co.uk A2B TRAVEL Uses Merseyside PTE 5 Preton Way, Prenton, Birkenhead CH43 3DU publications Tel: 0151 609 0600 www.a2b-travel.com ABELLIO LONDON No publications 301 Camberwell Road, London SE5 0TF Tel: 020 7805 3535 Fax: 020 7805 3502 Email: [email protected] www.abellio.co.uk ACKLAMS COACHES Leaflets Free Barmaston Close, Beverley HU17 0LA Tel: 01482 887666 Fax: 01482 874949 Email: [email protected],uk www.acklamscoaches.co.uk/local-service AIMÉE’S TRAVEL Leaflets Free Unit 1, Off Sunnyhill's Road, Barnfields Industrial Estate, Leek ST13 5RJ Tel: 01538 385050 Email: [email protected] www.aimeestravel.com/Services AINTREE COACHES Ltd Leaflets Free Unit 13, Sefton Industrial Estate, Sefton Lane, Maghull L31 8BX Tel: 0151 526 7405 Fax: 0151 520 0836 Email: [email protected] www.aintreecoachline.com (PHIL) ANSLOW & SONS COACHES Leaflets Free Unit 1, Varteg Industrial Estate, Varteg Road, Varteg, Pontypool NP4 7PZ Tel: 01495 775599 Email: [email protected] -

Operator Section

BUS OPERATORS IN THE BRITISH ISLES UPDATED 21/05/18 Please email any comments regarding this page to: [email protected] GREAT BRITAIN Please note that all details shown regarding timetables, maps or other publicity, refer only to PRINTED material and not to any other publications that an operator might be showing on its web site. A-LINE COACHES Leaflets Free Brandon Road, Binley, Coventry CV3 2JD Tel: 024 7645 0808 Fax: 024 7645 6434 Email: [email protected] www.a-linecoachescoventry.com A & M GROUP Uses Warwickshire CC publications Fleetname: Flexibus Unit 2, Churchlands Farm Industrial Estate, Bascote Road, Harbury CV33 9PL Tel: 01926 612487 Fax: 01926 614952 Email: [email protected] www.flexi-bus.co.uk A2B TRAVEL Uses Merseyside PTE 5 Preton Way, Prenton, Birkenhead CH43 3DU publications Tel: 0151 609 0600 www.a2b-travel.com ABELLIO LONDON No publications for Greater London, Fleetnames: Abellio London; Abellio Surrey but has leaflets for Surrey Free 301 Camberwell Road, London SE5 0TF Tel: 020 7805 3535 Fax: 020 7805 3502 Email: [email protected] www.abellio.co.uk ABUS Leaflets Free 104 Winchester Road, Brislington, Bristol BS4 3NL Tel: 0117 977 6126 Email: [email protected] www.abus.co.uk ACKLAMS COACHES Leaflets Free Barmaston Close, Beverley HU17 0LA Tel: 01482 887666 Fax: 01482 874949 Email: [email protected],uk www.acklamscoaches.co.uk/local-service AIMÉE’S TRAVEL Leaflets Free Unit 1, Off Sunnyhill's Road, Barnfields Industrial Estate, Leek ST13 5RJ Tel: 01538 385050 Email: [email protected] -

Leicester Environment City: Learning How to Make Local Agenda 21, Partnerships and Participation Deliver

LEICESTER’S LOCAL AGENDA 21 Leicester environment city: learning how to make Local Agenda 21, partnerships and participation deliver Ian Roberts Ian Roberts is Director of SUMMARY: This paper describes the pioneering experience of the city of Leices- Environ Sustainability. The ter (in the UK) over the last 10 years in developing its Local Agenda 21, and other early part of his career was spent in the private sector aspects of its work towards environmental improvement and sustainable develop- working in the oil industry ment. It includes details of measures to improve public transport and to reduce and, following an MBA, as congestion, traffic accidents, car use and air pollution. It also describes measures to a management consultant. In the late 1980s, he acted improve housing quality for low-income households, to reduce fossil fuel use and as chief executive of an increase renewable energy use and to make the city council’s own operations a investment company, at the model for reducing resource use and waste. It also describes how this was done – the time New Zealand’s specialist working groups that sought to make partnerships work (and their sixteenth largest company. In 1990, he was appointed strengths and limitations), the information programmes to win hearts and minds, director of Environment the many measures to encourage widespread participation (and the difficulties in City Trust with involving under-represented groups) and the measures to make local governments, responsibility for management of the businesses and other groups develop the ability and habit of responding to the local Leicester Environment City needs identified in participatory consultations.