The Law of Contract Damages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELA Annual Report 2012-2013

The Honourable Mr Justice Langsta President Employment Appeal Tribunal England & Wales David Latham President Employment Tribunals England & Wales Shona Simon President Employment Tribunals Scotland Lady Anne Smith (to March 2013) Chair Employment Appeal Tribunal Scotland Lady Valerie Stacey (from March 2013) Chair Employment Appeal Tribunal Scotland ELA Management Committee 2012 - 2014 Chair Richard Fox Deputy Chair Richard Linskell Treasurer Damian Phillips Secretary Fiona Bolton Editor, ELA Briefing Anna Henderson Chair, Training Committee Gareth Brahams Chair, Legislative & Policy Committee Bronwyn McKenna ELA Management Committee 2012 - 2014 Chair, International Committee Juliet Carp Chair, Pro Bono Committee Paul Daniels Representative of the Bar Paul Epstein QC In-house Representative Alison Leitch (to January 2013) Mark Hunt (from February 2013) Regional Representatives London & South East – Betsan Criddle and Eleena Misra Midlands – Ranjit Dhindsa North East – Anjali Sharma North West – Naeema Choudry Scotland – Joan Cradden South Wales – Nick Cooksey South West – Sean McHugh Members at Large Merrill April Stuart Brittenden Yvette Budé Karen Mortenson Catherine Taylor ELA Law Society Council Seat Tom Flanagan Life Vice Presidents Dame Janet Gaymer DBE QC Jane Mann Fraser Younson Vice President Joanne Owers ELA Support Head of Operations Lindsey Woods ELA Administration - Byword Sandra Harris Charley Masarati Emily Masarati Jeanette Masarati Claire Paley Finance Administrator Angela Gordon Website Manager Cynthia Clerk Website Support and Maintenance Ian Piper, Tellura Information Service Ltd Bronwen Reid, BR Enterprises Ltd PR Consultants Clare Turnbull, Kysen PR Chair Richard Fox, Kingsley Napley LLP Deputy Chair Richard Linskell, Ogletree Deakins This has been an extraordinary year for ELA and not just because 2013 marks our 20th Anniversary! Until relatively recently, there was a view that employment law had “plateaued”, and that the rate of change had started to mellow. -

September 14, 2010

CROSS-BORDER DISPUTE RESOLUTION: THE PERSPECTIVE FOR RUSSIA AND THE CIS The Lotte Hotel, Moscow | 8 bld.2, Novinskiy Boulevard SEPTEMBER 14, 2010 Judicial Assistance and Enforcement Proceedings International Asset Recovery Business and Corporate Raiding Disputes Involving Russian State and State Entities Late-Breaking Developments CONFERENCE WITH SUPPORT OF: STRATEGIC PARTNER: SPONSORS CONFERENCE STRATEGIC PARTNER CONFERENCE PARTNERS LUNCHEON SPONSOR PRE-CONFERENCE SPEAKER DINNER SPONSOR CONFERENCE DELEGATE BAG SPONSOR THERMAL MUGS SPONSOR NETWORKING BREAK SPONSORS MEETING SUPPORTER COOPERATING ENTITIES Federal Chamber of Advocates COOPERATING ENTITIES Moscow City Chamber of Advocates MEDIA SPONSORS Cross-Border Dispute Resolution: The Perspective for Russia and the CIS PROGRAM AGENDA All events to be held at the Lotte Hotel, Moscow located at 8 bld.2, Novinskiy Boulevard, unless otherwise indicated. 7:30 AM Registration and Breakfast Maxim Kulkov, Goltsblat BLP, Moscow, Russia Charles D. Schmerler, Fulbright & Jaworski LLP, New York, New York USA 8:30 AM Opening Session Moderator & Program Chair: Glenn P. Hendrix, Arnall Golden Gregory LLP, Atlanta, Georgia USA Welcome: Glenn P. Hendrix, Immediate Past Chair, American Bar Association 10:30 AM Networking Break Section of International Law, Arnall Golden Gregory LLP, Atlanta, Georgia USA 11:00 AM – 12:30 PM Introductions: Show Me the Money: Recovering Assets Abroad Andrew Somers, President and Chief Executive Officer, American Chamber of Commerce in Russia, Moscow, Russia "Winning" the case is great, but did you prepare upfront for the hard part -- actually collecting the money? While never easy against a recalcitrant Opening Remarks: debtor, recovery is especially difficult if the assets are tucked away The Honorable Aleksander Vladimirovich Konovalov, Minister of offshore. -

The Great Spill in the Gulf . . . and a Sea of Pure Economic Loss: Reflections on the Boundaries of Civil Liability

The Great Spill in the Gulf . and a Sea of Pure Economic Loss: Reflections on the Boundaries of Civil Liability Vernon Valentine Palmer1 I. INTRODUCTION A. Event and Aftermath What has been called the greatest oil spill in history, and certainly the largest in United States history, began with an explosion on April 20, 2010, some 41 miles off the Louisiana coast. The accident occurred during the drilling of an exploratory well by the Deepwater Horizon, a mobile offshore drilling unit (MODU) under lease to BP (formerly British Petroleum) and owned by Transocean.2 The well-head blowout resulted in 11 dead, 17 injured, and oil spewing from the seabed 5,000 ft. below at an estimated rate of 25,000-30,000 barrels per day.3 The Deepwater Horizon is technically described as “a massive floating, dynamically positioned drilling rig” capable of operating in waters 8,000 ft. deep.4 In maritime law, such a rig qualifies as a vessel; yet, as a MODU, the rig also qualifies as an offshore facility that may attract higher liability limits under the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA).5 Under these provisions the double designation as vessel and/or MODU 1. Thomas Pickles Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Eason Weinmann Center for Comparative Law, Tulane University. This paper was presented in October 2010 in Hong Kong at a conference convened under the auspices of the Centre for Chinese and Comparative Law of the City University of Hong Kong. The conference theme was “Towards a Chinese Civil Code: Historical and Comparative Perspectives.” The conference papers will be published in a forthcoming volume edited by Professors Chen Lei and Remco van Rhee. -

Smarter Manufacturing for a Smarter Australia

FOR A SMARTER AUSTRALIA PRIME MINISTER’S MANUFACTURING TASKFORCE REPORT OF THE NON-GOVERNMENT MEMBERS AUGUST 2012 A report of the non-Government members of the Prime Minister's Taskforce on Manufacturing, with support from the Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education (DIISRTE) © Commonwealth of Australia 2012 This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes subject to the inclusion of the source and no commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above requires the written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education, GPO Box 9839, Canberra ACT 2601. PRIME MINISTER’S MANUFACTURING TASKFORCE REPORT OF THE NON-GOVERNMENT MEMBERS AUGUST 2012 SMARTER MANUFACTURINGCONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Australia’s economic prospects 35 Productivity growth 35 SECTION 1 Competitiveness 35 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 6 Innovation the Australian way 36 Smarter Manufacturing for a Smarter Australia 6 Priority policy directions 7 SECTION 4 Australian manufacturing 8 THE POLICY FRAMEWORK 39 The Australian economy 8 Section summary 39 Next steps 9 Key policy challenges 40 Key concepts 9 Applying knowledge: by value adding Background to this report 10 through innovation 40 Terms of reference 10 UK: TICs / Catapult Centres About this report 11 Singapore: Biopolis and Fusionopolis 42 Building businesses: -

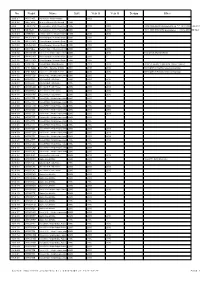

No. Regist Name Built Year O Year O Scrapp Other

No. Regist Name Built Year O Year O Scrapp Other 20527 WV 53 KTL Volvo B12M / Plaxton Paragon ? 2002 51556 M857 XHY Mercedes-Benz 811 D / Marshall 1994 ? 655 TOS 31YW Mercedes-Benz 609 D / Frank Guy 1995 2000 2008 24.08.1995 N613 GAH pierwsza rej. 28.02.2008 TOS 31YW 31.01.2018 zgłoszenie sprzedaży 52574 SBI 56J4 Mercedes-Benz 814 D / Plaxton Beaver1998 2 ? 2010 10.11.1998 S864 LRU pierwsza rej. 30.12.2010 SBI 56J4 32859 V859 HBY Dennis Trident 2 / Plaxton President 1999 2015 2016 34108 W435 CWX Volvo Olympian / Alexander Royale 2000 2000 ? 34110 W437 CWX Volvo Olympian / Alexander Royale 2000 2000 ? 34109 W436 CWX Volvo Olympian / Alexander Royale 2000 2000 ? 32947 W947 ULL Dennis Trident 2 / Alexander ALX400 2000 2014 2016 10036 W119 CWR Volvo B7LA / Wright Eclipse Fusion 2000 ? 2016 First Leeds (Hunslet Park) 34114 W434 CWX Volvo Olympian / Alexander Royale 2000 2000 ? 34112 W432 CWX Volvo Olympian / Alexander Royale 2000 2000 ? 62245 Y938 CSF Volvo B10BLE / Wright Renown 2001 2001 2018 2018 > Leicester CityBus Ltd. (Driver Trainer) 32075 KP51 WAO Volvo B7TL / Alexander ALX400 2001 2015 2016 08.10.2015 > First Somerset & Avon Ltd. 32076 KP51 WAU Volvo B7TL / Alexander ALX400 2001 2015 2016 08.10.2015 > First Somerset & Avon Ltd. 66952 WX55 TZO Volvo B7RLE / Wright Eclipse Urban 2005 2005 42898 WX05 RVC ADL Dart SLF / ADL Pointer 2005 2005 2016 42903 WX05 RVL ADL Dart SLF / ADL Pointer 2005 2005 2016 42557 WX05 UAO ADL Dart SLF / ADL Pointer 2005 2005 2015 42906 WX05 RVO ADL Dart SLF / ADL Pointer 2005 2005 2016 42916 WX05 RWF ADL Dart -

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

TORTS I PROFESSOR DEWOLF Summer 1994 July 8, 1994 MID-TERM SAMPLE ANSWER

TORTS I PROFESSOR DEWOLF Summer 1994 July 8, 1994 MID-TERM SAMPLE ANSWER QUESTION 1 I would consider claims against Larry Lacopo ("LL") and the Azure Shores Country Club. To establish liability, it would need to be proven that one of the parties breached a duty to Jason, either by being negligent or engaging in an activity for which strict liability is imposed, and that such a breach of duty was a proximate cause of injuries to him. Lacopo's Potential Liability We would argue that LL was negligent in striking the ball so hard without shouting "Fore!" To establish negligence, we would have to persuade the jury that a reasonably prudent person in the same or similar circumstances would have behaved differently. Perhaps reasonable golfers are aware of the need to avoid shots like the one that LL made; on the other hand, perhaps LL could convince the jury that he reasonably believed that the golf course had been designed so that shots would not pose a danger to anyone else. If the jury found LL negligent in hitting the ball so hard without having the skill to control it, then it would be easy to establish proximate cause. On the other hand, if the jury found that he should have shouted "Fore!" then it would still need to be shown that that failure was a proximate cause of injury. A jury would have to find that, more probably than not, the injury would not have occurred but for LL's negligence. Perhaps Jason or his grandfather would testify that, had someone shouted "Fore!" they would have at least kept an eye out for stray balls. -

The Leicestershire Historian

the Leicestershire Historian 1975 40p ERRATA The Book Reviews should be read in the order of pages 32, 34, 33, & 35. THE LEICESTERSHIRE HISTORIAN Vol 2 No 6 CONTENTS Page Editorial 3 Richard Weston and the First Leicester Directory 5 J D Bennett Loughborough's First School Board Election 10 31 March 1875 B Elliott Some Recollections of Belvoir Street, 15 Leicester, in 1865 H Hackett Bauthumley the Ranter 18 E Welch The Day of the Year - November 14th 1902 25 C S Dean Chartists in Loughborough 27 P A Smith Book Reviews 32 Mrs G K Long, J Goodacre The Leicestershire Historian, which is published annually is the magazine of the Leicestershire Local History Council, and is distributed free to members. The Council exists to bring local history to the doorstep of all interested people in Leicester and Leicestershire, to provide for them opportunities of meeting together, to act as a co-ordinating body between the various Societies in the County and to promote the advancement of local history studies. A series of local history meetings is arranged throughout the year and the programme is varied to include talks, film meetings, outdoor excursions and an annual Members' Evening held near Christmas. The Council also encourages and supports local history exhibitions; a leaflet giving advice on the promotion of such an exhibition is available from the Secretary. The different categories of membership and the subscriptions are set out below. If you wish to become a member, please contact the Secretary, who will also be pleased to supply further information about membership and the Annual Programme. -

Leicester Environment City: Learning How to Make Local Agenda 21, Partnerships and Participation Deliver

Leicester environment city: learning how to make Local Agenda 21, partnerships and participation deliver Ian Roberts Ian Roberts is Director of SUMMARY: This paper describes the pioneering experience of the city of Leices- Environ Sustainability. The ter (in the UK) over the last 10 years in developing its Local Agenda 21, and other early part of his career was spent in the private sector aspects of its work towards environmental improvement and sustainable develop- working in the oil industry ment. It includes details of measures to improve public transport and to reduce and, following an MBA, as congestion, traffic accidents, car use and air pollution. It also describes measures to a management consultant. In the late 1980s, he acted improve housing quality for low-income households, to reduce fossil fuel use and as chief executive of an increase renewable energy use and to make the city council's own operations a investment company, at the model for reducing resource use and waste. It also describes how this was done – the time New Zealand’s specialist working groups that sought to make partnerships work (and their sixteenth largest company. In 1990, he was appointed strengths and limitations), the information programmes to win hearts and minds, director of Environment the many measures to encourage widespread participation (and the difficulties in City Trust with involving under-represented groups) and the measures to make local governments, responsibility for management of the businesses and other groups develop the ability and habit of responding to the local Leicester Environment City needs identified in participatory consultations. initiative. -

CS Group Buys AIM for £5.3M Earlier This Month the AIM-Listed Computer Software Group Bought Hull-Based Legal Systems Supplier AIM for £5.3 Million in Cash

www.legaltechnology.com CS Group buys AIM for £5.3m Earlier this month the AIM-listed Computer Software Group bought Hull-based legal systems supplier AIM for £5.3 million in cash. AIM’s audited accounts to 30 April 2005 show a pre-tax loss from continuing operations of £107k and gross assets of £7.5 million. Since then AIM has disposed of another division and consequently pre-tax losses for the year to 30 April 2006 are expected to increase. However the CS Group says it is confident that “cost savings and synergies resulting from the acquisition CPL expect £850k IT will result in a significant increase in future profitability”. Currently income from recurring support contracts account payback in year one for approximately 51% of AIM’s annual sales. Europe’s largest conveyancing operation Countrywide Property Lawyers is investing Following the acquisition Jim Chase is to continue as £850,000 in an upgrade of their Visualfiles managing director of AIM’s legal software business unit case management and SOS practice within the CS Group. All other AIM Group directors have management software. CPL, who resigned. Commenting on the deal, CS Group chief originally went with a Visualfiles/SOS executive Vin Murria said she was “confident AIM, with its solution in 1997 but then flirted with and strong and stable client base, will steadily grow in sales subsequently abandoned a bespoke and profits. It will provide a sound base from which CS project called Fusion, say they are Group can develop a significant position in the legal confident the upgrade will pay for itself sector, in which we intend to become a leading supplier.” within the first year of implementation. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS (ALPHABETICALLY) 7-Eleven Stores Amcor A.P. MOLLER- MAERSK A/S AMEC Mining & Metals ABB Australia AMEC Oil & Gas Abbott Australasia Amgen Australia AbbVie Australia AMP Services Accolade Wines AMT Group Acrux DDS Amway of Australia Actavis Australia Anglican Retirement Villages Diocese of Sydney Actelion Pharmaceuticals ANL Container Line Adelaide Brighton APL Co Adidas Australia Apotex AECOM Australia APT Management Services (APA Group) Afton Chemical Asia Pacific Arch Wood Protection (Aust) AGC Arts Centre Melbourne AGL Energy ASC AIA Australia Ashland Hercules Water Technologies (Australia) Aimia Association of Professionals, Engineers, Scientists and Managers Australia Air Liquide Australia Astellas Pharma Alcon Laboratories Australia AstraZeneca Alfa Laval Australia ATCO Australia Alinta Servco (Alinta Energy) Aurora Energy Allergan Australia AUSCOAL Services Allianz Global Assistance Auscript Australasia Allied Mills Ausenco Alpha Flight Services Aussie Farmers Direct Alphapharm Aussie Home Loans Alstom Australand Property Group Ambulance Victoria Australian Agricultural Company © March 2013 Mercer Consulting (Australia) Pty Ltd Quarterly Salary Review 1.5 INTRODUCTION Australian Catholic University Billabong Australian Football League Biogen Idec Australia Australian Institute of Company Directors BioMerieux Australia Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Bio-Rad Laboratories Organistaion (ANSTO) Biota Holdings Australian Pharmaceutical Industries (Priceline, Soul Pattinson Chemist) BISSELL -

Why Firms Still Need to Be Careful in Good Markets 21St September 2015 Authors: Tony Williams; Steve Cottee

Beware of the upturn – why firms still need to be careful in good markets 21st September 2015 Authors: Tony Williams; Steve Cottee As the results for 2014-15 show a sustained if gradual improvement in law firms financial performance, together with the news of Gateley's successful IPO it is tempting to assume that the worst is now behind law firms after a gruelling period following the financial crisis. However, law firms need to be wary of the upturn and ensure that their firm is well placed to weather the storms that will buffet the legal market for many years to come. In our view there are six factors that law firms need to pay particular attention to if they are going to survive and thrive over the next few years. Cash Firms have increased their long term debt (over one year) from £5.75bn in 2010 to £7.35bn in 2014. Conversely short term debt, mostly overdrafts, has reduced from £2.4bn in 2011 to £1.8bn in 2014. Firms have however received a very significant cash infusion by way of the estimated £1bn of capital injected by fixed share partners to meet the recent requirements of HMRC. Banks still see law firms as a relatively good risk but a few high profile failures may see credit committees becoming far less accommodating and the cost of facilities rise. Crucially the capital injection from fixed share partners many firms benefitted from last year will not be available this year, at a time when arguably there will be an even greater need for cash than before.