1 Why Is Penelope Still Waiting? the Missing Feminist Reappraisal of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Construcción Histórica En La Cinematografía Norteamericana

Tesis doctoral Luis Laborda Oribes La construcción histórica en la cinematografía norteamericana Dirigida por Dr. Javier Antón Pelayo Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Departamento de Historia Moderna Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona 2007 La historia en la cinematografía norteamericana Luis Laborda Oribes Agradecimientos Transcurridos ya casi seis años desde que inicié esta aventura de conocimiento que ha supuesto el programa de doctorado en Humanidades, debo agradecer a todos aquellos que, en tan tortuoso y apasionante camino, me han acompañado con la mirada serena y una palabra de ánimo siempre que la situación la requiriera. En el ámbito estrictamente universitario, di mis primeros pasos hacia el trabajo de investigación que hoy les presento en la Universidad Pompeu Fabra, donde cursé, entre las calles Balmes y Ramon Trias Fargas, la licenciatura en Humanidades. El hado o mi más discreta voluntad quisieron que iniciara los cursos de doctorado en la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, donde hoy concluyo felizmente un camino repleto de encuentros. Entre la gente que he encontrado están aquellos que apenas cruzaron un amable saludo conmigo y aquellos otros que hicieron un alto en su camino y conversaron, apaciblemente, con el modesto autor de estas líneas. A todos ellos les agradezco cuanto me ofrecieron y confío en haber podido ofrecerles yo, a mi vez, algo más que hueros e intrascendentes vocablos o, como escribiera el gran bardo inglés, palabras, palabras, palabras,... Entre aquellos que me ayudaron a hacer camino se encuentra en lugar destacado el profesor Javier Antón Pelayo que siempre me atendió y escuchó serenamente mis propuestas, por muy extrañas que resultaran. -

The Humour of Homer

The Humour of Homer Samuel Butler A lecture delivered at the Working Men's College, Great Ormond Street 30th January, 1892 The first of the two great poems commonly ascribed to Homer is called the Iliad|a title which we may be sure was not given it by the author. It professes to treat of a quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles that broke out while the Greeks were besieging the city of Troy, and it does, indeed, deal largely with the consequences of this quarrel; whether, however, the ostensible subject did not conceal another that was nearer the poet's heart| I mean the last days, death, and burial of Hector|is a point that I cannot determine. Nor yet can I determine how much of the Iliadas we now have it is by Homer, and how much by a later writer or writers. This is a very vexed question, but I myself believe the Iliadto be entirely by a single poet. The second poem commonly ascribed to the same author is called the Odyssey. It deals with the adventures of Ulysses during his ten years of wandering after Troy had fallen. These two works have of late years been believed to be by different authors. The Iliadis now generally held to be the older work by some one or two hundred years. The leading ideas of the Iliadare love, war, and plunder, though this last is less insisted on than the other two. The key-note is struck with a woman's charms, and a quarrel among men for their possession. -

Ulysses Notes Joe Kelly Chapter 1: Telemachus Stephen Dedalus, A

Ulysses Notes Joe Kelly Chapter 1: Telemachus Stephen Dedalus, a young poet employed as a school teacher; Buck Mulligan, a med student; and an Englishman called Haines, who is in Ireland to study Celtic culture, spend their morning in their Martello Tower at the seaside resort town of Sandycove, south of Dublin. Stephen, who is mourning for his dead mother, watches Buck shave on the parapet, they discuss things, Buck goes inside to cook breakfast. They all eat while a local farm woman brings them their milk. Then they walk Martello (now called the "Joyce") Tower at down to the "Forty Foot Hole," where Buck Sandycove swims in Dublin Bay. Pay careful attention to what the swimmers say about the Odyssey, Odysseus was missing, Bannons and the photo girl. presumed dead by most, for ten years after the end of the Trojan War, and Look for parallels between Stephen and his palace and wife in Ithaca were Hamlet, on one hand, and Telemachus, the beset by "suitors" who wanted to son of Odysseus, on the other. In the become king. Ulysses is a sequel to Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which is a bildungsroman starring Stephen Dedalus. That novel ended with Stephen graduating from University College, Dublin and heading off for Paris to launch his literary career. Two years later, he's back in Dublin, having been summoned home by his mother's illness. So he's something of an Icarus figure also, having tried to fly out of the labyrinth of Ireland to freed om, but having fallen, so to speak. -

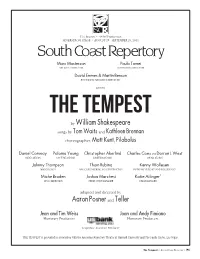

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

Sundance Institute Announces Casts for Summer Theatre Laboratory

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For more information contact: June 21, 2006 Irene Cho [email protected], 801.328.3456 SUNDANCE INSTITUTE ANNOUNCES CASTS FOR SUMMER THEATRE LABORATORY AWARD-WINNING ACTORS ANTHONY RAPP, RAÚL ESPARZA AND OTHERS TO WORKSHOP SEVEN NEW PLAYS AT JULY LAB IN UTAH Salt Lake City, UT – Today, Sundance Institute announced the acting ensemble for the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory, to be held July 10-30, 2006 at the Sundance Resort in Utah. The company includes: Bradford Anderson, Nancy Anderson, Whitney Bashor, Judy Blazer, Reg E. Cathey, Will Chase, Johanna Day, Raúl Esparza, Jordan Gelber, Kimberly Hebert Gregory, Carla Harting, Roderick Hill, Nicholas Hormann, Christina Kirk, Ezra Knight, Judy Kuhn, Anika Larsen, Piter Marek, Kelly McCreary, Chris Messina, Jennifer Mudge, Novella Nelson, Toi Perkins, Anthony Rapp, Gareth Saxe, Tregoney Shepherd, Michael Stuhlbarg and Price Waldman. The seven plays to be developed at the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory include: CITIZEN JOSH, by Josh Kornbluth, directed by David Dower, an improvisational solo show which strives to rescue “democracy” from the sloganeers in a personal autobiographical format; CURRENT NOBODY, by Melissa James Gibson, directed by Daniel Aukin, a modern reinterpretation of Homer’s The Odyssey; GEOMETRY OF FIRE, by Stephen Belber, directed by Lucie Tiberghien, which weaves the story of an American reservist just back from Iraq and a Saudi-American citizen investigating his father’s death; THE EVILDOERS, by David Adjmi, directed by Rebecca Taichman, a play in which the marriage of two couples unravel in a dark yet comedic context; …AND JESUS MOONWALKS THE MISSISSIPPI, by Marcus Gardley, directed by Matt August, a poetic retelling of the Demeter myth set during the Civil War; KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS, book by Robert L. -

Volume 19, No. 3, June 1958

Vol. 19, No. 3 Published by the SOCIALIST WORKERS PARTY .June, 1958 116 UNIVERSITY PLACE ~;m~m~~i! ::::::::::::: ::::mmm NEW YORK 3, N EW YORK. :::: :: :: ::~:. 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 CONTENTS 1. WEISS ARTICLE ON CLARK -- Letter to the Political and National Committee -- by Sam Marcy 1 2. HOWARD FAST -- Letter to the Political Comm itr,ee -- by Gross 11 3. A FOOTNOTE ON R EGR OUPI~ T -- by V. Grey 14 4. Letter to the Political Co mm ittee -- by Milton Alvi n 16 25¢ 1\1\11\1\1\~ll l llII11!1!!!I!1111 ~: The material in tilis bulletin has been previously circulated to members of the National Corami ttea as part of the discussion on the regroupment policy_ It is now published for the information of the party rr.embership. Tom Kerry Organization Secretary { September 25, 1957 Political Committee National Committee BgJ Weiss .4xticle on Clark Dear Comrade s: I note with satisfaction the proposal of the Secretariat to initiate a discussion in the PC on the regroupment develop ments, and to follow it up with a Plenum. This letter is intended to be a preli~inary contribution to the PC discussion. I ".Tant to protest most vigorously arainst the political line of the article by Comrade Murry 11eiss in the September 16th issue of the MILITANT regarding the resignation of Joseph Clark from the CP and as foreign editor of the DAILY tJuHKER. Comrade Weiss makes the following important points reE;arding Clark's letter of resignation. Clark has attacked the Stalinist versi)n of oroletarian internationalism as expressed by the Duclos ietter to the recent CP convention, and expressed solidarity with the Hungarian insurrection. -

Another Penelope: Margaret Atwood's the Penelopiad

Monica Bottez ANOTHER PENELOPE: MARGARET ATWOOD’S THE PENELOPIAD Keywords: epic; quest; hybrid genre; indeterminacy; postmodernism Abstract: The paper sets out to present The Penelopiad as a rewriting of Homer’s Odyssey with Penelope as the narrator. Using the Homeric intertext as well as other Greek sources collected by Robert Graves in his book The Greek Myths and Tennyson‟s “Ulysses,” it evidences the additions that the new narrative perspective has stimulated Atwood to imagine. The Penelopiad is read as propounding a new genre, the female epic or romance where the heroine’s quest is analysed on analogy with the traditional romance pattern. The paper dwells on the contradictory and parody- like versions of events and characters embedded in the text: has Penelope been the perfect patient devoted wife, a cunning lustful pretender, or the High Priestess of an Artemis cult? In conclusion, the reader can never know the truth, being tied up in the utterly puzzling indeterminacy of meaning specific to postmodernism. The title of Margaret Atwood‟s novella makes the reader expect a rewriting of Homer‟s Odyssey, which is precisely what the author does in order to enrich it with new interpretations; since myths and legends are the repository of our collective desires, fears and longings, their actuality can never be exhausted: Atwood has used mythology in much the same way she has used other intertexts like folk tales, fairy tales, and legends, replaying the old stories in new contexts and from different perspectives – frequently from a woman‟s point of view – so that the stories shimmer with new meanings. -

A Level Classical Civilisation Candidate Style Answers

Qualification Accredited A LEVEL Candidate style answers CLASSICAL CIVILISATION H408 For first assessment in 2019 H408/11: Homer’s Odyssey Version 1 www.ocr.org.uk/alevelclassicalcivilisation A Level Classical Civilisation Candidate style answers Contents Introduction 3 Question 3 4 Question 4 8 Essay question 12 2 © OCR 2019 A Level Classical Civilisation Candidate style answers Introduction OCR has produced this resource to support teachers in interpreting the assessment criteria for the new A Level Classical Civilisation specification and to bridge the gap between new specification’s release and the availability of exemplar candidate work following first examination in summer 2019. The questions in this resource have been taken from the H408/11 World of the Hero specimen question paper, which is available on the OCR website. The answers in this resource have been written by students in Year 12. They are supported by an examiner commentary. Please note that this resource is provided for advice and guidance only and does not in any way constitute an indication of grade boundaries or endorsed answers. Whilst a senior examiner has provided a possible mark/level for each response, when marking these answers in a live series the mark a response would get depends on the whole process of standardisation, which considers the big picture of the year’s scripts. Therefore the marks/levels awarded here should be considered to be only an estimation of what would be awarded. How levels and marks correspond to grade boundaries depends on the Awarding process that happens after all/most of the scripts are marked and depends on a number of factors, including candidate performance across the board. -

Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Dorothy Johnson GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los ANGELES For my parents, Alice and John Winter, and for Johnny Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748 — 1825). The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis, 1818 Benedicte Gilman, Editor (detail). Oil on canvas, 87.2 x 103 cm (34% x 40/2 in.). Elizabeth Burke Kahn, Production Coordinator Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum (87.PA.27). Jeffrey Cohen, Designer Lou Meluso, Photographer Frontispiece: (Getty objects, 87.PA.27, 86.PA.740) Jacques-Louis David. Self-Portrait, 1794. Oil on canvas, 81 x 64 cm (31/8 x 25/4 in.). Paris, © 1997 The J. Paul Getty Museum Musee du Louvre (3705). © Photo R.M.N. 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, California 90265-5799 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs Mailing address: provided) courtesy of the owners, unless otherwise P.O. Box 2112 indicated. Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 Typography by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Library of Congress Austin, Texas Cataloging-in-Publication Data Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., Hong Kong Johnson, Dorothy. Jacques-Louis David, the Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis / Dorothy Johnson, p. cm.—(Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references (p. — ). ISBN 0-89236-236-7 i. David, Jacques Louis, 1748 — 1825. Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis. 2. David, Jacques Louis, 1748-1825 Criticism and interpretation. 3. Telemachus (Greek mythology)—Art. 4. Eucharis (Greek mythology)—Art. I. Title. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. the Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making

New England Classical Journal Volume 40 Issue 3 Pages 213-216 11-2013 Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. The Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making. Anne Mahoney Tufts University Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/necj Recommended Citation Mahoney, Anne (2013) "Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. The Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making.," New England Classical Journal: Vol. 40 : Iss. 3 , 213-216. Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/necj/vol40/iss3/5 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Classical Journal by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. BOOK REVIEWS Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. The Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies, 2012. Distributed by Harvard University Press. Pp. 350. Paper (ISBN 978-0-674- 06062-3) $24.95. his is a linguistic study of a1h6s and related words in epic, particularly the Odyssey but also the Iliad. Bonifazi considers first Thow a11T6s and EKE'ivos are contrasted when they refer to Odysseus, then how all the various av- words are similar. Her main tool is pragmatics, building on work by many scholars on discourse grammar in both Greek and Latin. Because she goes through a lot of basic background in this area of linguistics, with a copious bibliography, 25 pages, the book seems accessible to non-linguist classicists, though this is not really an introduction to pragmatics. In the introduction, Bonifazi says that "the general aim of this work is to contribute to an update of the grammatical accounts of some words in accord with notions and concepts from contemporary linguistics that are applicable to Homer" (10), observing that this kind of study adds precision to our understanding of pronouns, particles, and similar words, and that attention to the dialogue context can "shed more light on the standpoint of either the author or the internal characters" (11). -

The Penelopiad

THE PENELOPIAD Margaret Atwood EDINBURGH • NEW YORK • MELBOURNE For my family ‘… Shrewd Odysseus! … You are a fortunate man to have won a wife of such pre-eminent virtue! How faithful was your flawless Penelope, Icarius’ daughter! How loyally she kept the memory of the husband of her youth! The glory of her virtue will not fade with the years, but the deathless gods themselves will make a beautiful song for mortal ears in honour of the constant Penelope.’ – The Odyssey, Book 24 (191–194) … he took a cable which had seen service on a blue-bowed ship, made one end fast to a high column in the portico, and threw the other over the round-house, high up, so that their feet would not touch the ground. As when long-winged thrushes or doves get entangled in a snare … so the women’s heads were held fast in a row, with nooses round their necks, to bring them to the most pitiable end. For a little while their feet twitched, but not for very long. – The Odyssey, Book 22 (470–473) CONTENTS Introduction i A Low Art ii The Chorus Line: A Rope-Jumping Rhyme iii My Childhood iv The Chorus Line: Kiddie Mourn, A Lament by the Maids v Asphodel vi My Marriage vii The Scar viii The Chorus Line: If I Was a Princess, A Popular Tune ix The Trusted Cackle-Hen x The Chorus Line: The Birth of Telemachus, An Idyll xi Helen Ruins My Life xii Waiting xiii The Chorus Line: The Wily Sea Captain, A Sea Shanty xiv The Suitors Stuff Their Faces xv The Shroud xvi Bad Dreams xvii The Chorus Line: Dreamboats, A Ballad xviii News of Helen xix Yelp of Joy xx Slanderous Gossip xxi The Chorus Line: The Perils of Penelope, A Drama xxii Helen Takes a Bath xxiii Odysseus and Telemachus Snuff the Maids xxiv The Chorus Line: An Anthropology Lecture xxv Heart of Flint xxvi The Chorus Line: The Trial of Odysseus, as Videotaped by the Maids xxvii Home Life in Hades xxviii The Chorus Line: We’re Walking Behind You, A Love Song xxix Envoi Notes Acknowledgements Introduction The story of Odysseus’ return to his home kingdom of Ithaca following an absence of twenty years is best known from Homer’s Odyssey.