Digital Media: an Emerging Barometer of Public Opinion in Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Najib's Fork-Tongue Shows Again: Umno Talks of Rejuvenation Yet Oldies Get Plum Jobs at Expense of New Blood

NAJIB'S FORK-TONGUE SHOWS AGAIN: UMNO TALKS OF REJUVENATION YET OLDIES GET PLUM JOBS AT EXPENSE OF NEW BLOOD 11 February 2016 - Malaysia Chronicle The recent appointments of Tan Sri Annuar Musa, 59, as Umno information chief, and Datuk Seri Ahmad Bashah Md Hanipah, 65, as Kedah menteri besar, have raised doubts whether one of the oldest parties in the country is truly committed to rejuvenating itself. The two stalwarts are taking over the duties of younger colleagues, Datuk Ahmad Maslan, 49, and Datuk Seri Mukhriz Mahathir, 51, respectively. Umno’s decision to replace both Ahmad and Mukhriz with older leaders indicates that internal politics trumps the changes it must make to stay relevant among the younger generation. In a party where the Youth chief himself is 40 and sporting a greying beard, Umno president Datuk Seri Najib Razak has time and again stressed the need to rejuvenate itself and attract the young. “Umno and Najib specifically have been saying about it (rejuvenation) for quite some time but they lack the political will to do so,” said Professor Dr Arnold Puyok, a political science lecturer from Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. “I don’t think Najib has totally abandoned the idea of ‘peremajaan Umno’ (rejuvenation). He is just being cautious as doing so will put him in a collision course with the old guards.” In fact, as far back as 2014, Umno Youth chief Khairy Jamaluddin said older Umno leaders were unhappy with Najib’s call for rejuvenation as they believed it would pit them against their younger counterparts. He said the “noble proposal” that would help Umno win elections could be a “ticking time- bomb” instead. -

Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom – a Malaysian Case Study on Blogging

20th BILETA Conference: Over-Commoditised; Over- Centralised; Over-Observed: the New Digital Legal World? Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom: A Malaysian Case Study on Blogging Towards a Democratic Culture Tang Hang Wu Assistant Professor, Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore. 1 Introduction Online personal diaries known as web logs or blogs have recently entered into mainstream consciousness.1 The U.S. dictionary, Merriam- Webster picked the word ‘blog’ as the word of the year in 2004 on the basis that it was the most looked up word.2 The advance of technology has enabled diarists to publish their writings on the Internet almost immediately and thereby reaching a worldwide audience. Anyone with access to a computer, from Baghdad to Beijing, from Kenya to Kuala Lumpur, can start a blog. The fact that blogs can be updated instantaneously made them exceedingly popular especially in times of crisis when people trawl the Internet for every scrap of news and information. It is unsurprising that the terror attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City on September 11, 2001 and the recent US led war in Iraq have caused traffic to several blogs to increase dramatically.3 Blogs with a political slant gained further prominence with the recent fiercely contested and deeply polarized 2004 U.S. elections as the candidates and their supporters used the Internet aggressively in their campaigns.4 Besides its effect on domestic US politics and providing an intensely personal coverage of significant events like September 11 and the Iraq 1 war, blogs maintained by people living under less democratic regimes have also started to make an impact.5 In countries where no independent media exists, blogs are beginning to act as an important medium of dissemination of information to the public as well as providing the outside world a glimpse into what actually goes on in these regimes.6 Quite apart from performing the role of spreading vital news and information, blogs are also changing the social conditions in these societies with regard to freedom of speech. -

Senarai Penuh Calon Majlis Tertinggi Bagi Pemilihan Umno 2013 Bernama 7 Oct, 2013

Senarai Penuh Calon Majlis Tertinggi Bagi Pemilihan Umno 2013 Bernama 7 Oct, 2013 KUALA LUMPUR, 7 Okt (Bernama) -- Berikut senarai muktamad calon Majlis Tertinggi untuk pemilihan Umno 19 Okt ini, bagi penggal 2013-2016 yang dikeluarkan Umno, Isnin. Pengerusi Tetap 1. Tan Sri Badruddin Amiruldin (Penyandang/Menang Tanpa Bertanding) Timbalan Pengerusi Tetap 1. Datuk Mohamad Aziz (Penyandang) 2. Ahmad Fariz Abdullah 3. Datuk Abd Rahman Palil Presiden 1. Datuk Seri Mohd Najib Tun Razak (Penyandang/Menang Tanpa Bertanding) Timbalan Presiden 1. Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin (Penyandang/Menang Tanpa Bertanding) Naib Presiden 1. Datuk Seri Dr Ahmad Zahid Hamidi (Penyandang) 2. Datuk Seri Hishammuddin Tun Hussein (Penyandang) 3. Datuk Seri Mohd Shafie Apdal (Penyandang) 4. Tan Sri Mohd Isa Abdul Samad 5. Datuk Mukhriz Tun Dr Mahathir 6. Datuk Seri Mohd Ali Rustam Majlis Tertinggi: (25 Jawatan Dipilih) 1. Datuk Seri Shahidan Kassim (Penyandang/dilantik) 2. Datuk Shamsul Anuar Nasarah 3. Datuk Dr Aziz Jamaludin Mhd Tahir 4. Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob (Penyandang) 5. Datuk Raja Nong Chik Raja Zainal Abidin (Penyandang/dilantik) 6. Tan Sri Annuar Musa 7. Datuk Zahidi Zainul Abidin 8. Datuk Tawfiq Abu Bakar Titingan 9. Datuk Misri Barham 10. Datuk Rosnah Abd Rashid Shirlin 12. Datuk Musa Sheikh Fadzir (Penyandang/dilantik) 13. Datuk Seri Ahmad Shabery Cheek (Penyandang) 4. Datuk Ab Aziz Kaprawi 15. Datuk Abdul Azeez Abdul Rahim (Penyandang) 16. Datuk Seri Mustapa Mohamed 17. Datuk Sohaimi Shahadan 18. Datuk Seri Idris Jusoh (Penyandang) 19. Datuk Seri Mahdzir Khalid 20. Datuk Razali Ibrahim (Penyandang/dilantik) 21. Dr Mohd Puad Zarkashi (Penyandang) 22. Datuk Halimah Mohamed Sadique 23. -

Annuar Reappointed

Headline Annuar reappointed as Mara chairman MediaTitle New Straits Times Date 13 Aug 2015 Color Full Color Section Local News Circulation 74,711 Page No 20 Readership 240,000 Language English ArticleSize 136 cm² Journalist N/A AdValue RM 4,688 Frequency Daily PR Value RM 14,064 Annuar reappointed as Mara chairman PUTRAJAYA: The Majlis Amanah Rakyat implementing policies and plans by the min (Mara) has reappointed Tan Sri Annuar Musa istry and achieving the objectives of the Na as chairman effective yesterday. tional Transformation Plan," he said yester His contract ended on July 17 after day. holding the post for two years since Annuar, 59, is also Ketereh mem July 19,2013. ber of parliament and has been an His reappointment was an Urn no supreme council member nounced by Rural and Regional De since 2013. velopment Minister Datuk Seri Is He holds a Master's in Construc mail Sabri Yaakob, who also an tion Management from University nounced the appointment of Datuk College of London, and a Bachelor's Zahidi Zainul Abidin as Rubber In degree in Town and Country Plan dustry Smallholders Authority (Ris ning from Universiti Teknologi da) chairman. Zahidi's chairmanship will begin He has also served as youth and on Sept 1. sports minister from 1990 to 1993 and Ismail believed the appointments rural development minister from of Annuar and Zahidi would help 1993 to 1999. Mara and Risda achieve the min Zahidi, 54 who is Padang Besar istry's objective. MP, received his diploma in Public "I believe that both their appoint Administration from Universiti ments will lead Mara and Risda in effectively Teknologi Mara.. -

WHY ALL the FUSS? House Seller Issues SD, Debunks Opposition Claims

沙布丁缺席一对一会晤 PENANG HAS 首长临时邀请媒体参观私邸无隐瞒 THE LOWEST DEBTS pg pg 3 1 FREE buletin Competency Accountability Transparency http:www.facebook.com/buletinmutiara March 16 - 31, 2016 http:www.facebook.com/cmlimguaneng WHY ALL THE FUSS? House seller issues SD, debunks opposition claims Story by Chan Lilian will be taken against those mak- Pix by Shum Jian-Wei ing accusations. “I also wish to clarify here that PHANG Li Koon, who sold her I am not a director nor share- house to Chief Minister Lim holder of KLIDC company I have no business Guan Eng, issued a statutory which has successfully bid for dealings with the state declaration (SD) on March 22 the Taman Manggis land under government where she debunked allegations an open tender. I am also not by certain quarters. involved in the management of - PHANG “CM and his family have been the company. I reserve my right my good tenants for the last six to legal action against any party years. To me, CM is a respectable should they try to make unneces- leader and I feel very honoured sary connection to complicate the to sell my property to him. I think matter and drag me into this Betty, a former lawyer and Penang has done well under his controversy,” Phang warned. assemblymember, had shown the administration. Most important- Phang’s explanation that the media members her kitchen, liv- ly, I have sold my property to a price was fixed in 2012 has al- ing room and the array of her person I respect. I have no regret layed all doubts. -

BMJ in the News Is a Weekly Digest of BMJ Stories, Plus Any Other News

BMJ in the News is a weekly digest of BMJ stories, plus any other news about the company that has appeared in the national and a selection of English-speaking international media. This week’s (14 Nov-20 Dec) highlights include: The BMJ Christmas Research: Do heads of government age more quickly? Christmas Research: Parliamentary privilege—mortality in members of the Houses of Parliament compared with the UK general population In presidential politics, to the victors go the spoiled life expectancy - Reuters 15/12/2015 Leading a Nation Takes Years Off Life, Study Suggests - New York Times 14/12/2015 New study: Heads of state live shorter lifespans - CNN 14/12/2015 Over 200 articles listed on Google News, including: US/Canada - Washington Post, Washington Times, Fox News, U.S. News & World Report, USA TODAY, CTV News, Vox, Huffington Post Canada, National Post Canada, Business Insider, The Chronicle Journal, STAT, HealthDay, Discovery News, Newsmax, Inquirer.net India - The Times of India, Business Standard, New Kerala, The Indian Express, Asian New International ROW: The Australian (blog), Sydney Morning Herald, Herald Sun, NEWS.com.au, South China Morning Post, The Times of Israel, Arab News (Saudi Arabia), Gulf News (UAE), Straits Times (Singapore), Star Malaysia, The Manila Times, Economy Lead, Science Codex, Medical Daily, Medical Xpress, Medical News Today Christmas Research: “Gunslinger’s gait”: a new cause of unilaterally reduced arm swing Putin walks with KGB-trained 'gunslinger's gait': study - CTV News 14/12/2015 -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Download Download

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN BUSINESS AND SOCIAL SCIENCE 9(6)(2020) 12-23 Research in Business & Social Science IJRBS VOL 9 NO 6 ISSN: 2147-4478 Available online at www.ssbfnet.com Journal homepage: https://www.ssbfnet.com/ojs/index.php/ijrbs Key adaptations of SME restaurants in Malaysia amidst the COVID- 19 Pandemic Hao Bin Jack Lai (a), Muhammad Rezza Zainal Abidin (b), Muhamad Zulfikri Hasni (c), Muhammad Shahrim Ab Karim (d), Farah Adibah Che Ishak (e) (a) Department of Food Service and Management, Faculty of Food Science and Technology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: SME restaurants have reported declined earnings and faced challenges to remain open during the Movement Control Order (MCO) period imposed by the Malaysian government due to the Coronavirus Received 05 October 2020 (COVID-19) outbreak. SME decision-makers were observed to be making changes regarding their Received in rev. form 14 Oct. 2020 day-to-day operations and management strategies to mitigate MCO restrictions. This paper reviewed Accepted 18 October 2020 the significant adaptations made by SME restaurants in Malaysia throughout the MCO period through multiple primary and secondary literature utilizing a pragmatic approach. Three (3) prominent areas of adaptations made by decision-makers have been identified based upon ceaseless news reports and Keywords: media contents. The adaptations made commonly depict actions to (i) Nurture Creativity, (ii) Sustain Reputation, and (iii) Maintain Profitability. The outcomes of this paper provide essential survival COVID-19; SME restaurants; guides for SME restauranteurs to embrace the COVID-19 outbreak. -

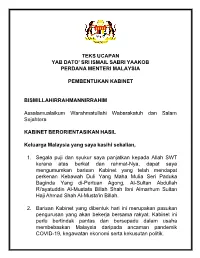

Teks-Ucapan-Pengumuman-Kabinet

TEKS UCAPAN YAB DATO’ SRI ISMAIL SABRI YAAKOB PERDANA MENTERI MALAYSIA PEMBENTUKAN KABINET BISMILLAHIRRAHMANNIRRAHIM Assalamualaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh dan Salam Sejahtera KABINET BERORIENTASIKAN HASIL Keluarga Malaysia yang saya kasihi sekalian, 1. Segala puji dan syukur saya panjatkan kepada Allah SWT kerana atas berkat dan rahmat-Nya, dapat saya mengumumkan barisan Kabinet yang telah mendapat perkenan Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Al-Sultan Abdullah Ri'ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah Ibni Almarhum Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Al-Musta'in Billah. 2. Barisan Kabinet yang dibentuk hari ini merupakan pasukan pengurusan yang akan bekerja bersama rakyat. Kabinet ini perlu bertindak pantas dan bersepadu dalam usaha membebaskan Malaysia daripada ancaman pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi serta kekusutan politik. 3. Umum mengetahui saya menerima kerajaan ini dalam keadaan seadanya. Justeru, pembentukan Kabinet ini merupakan satu formulasi semula berdasarkan situasi semasa, demi mengekalkan kestabilan dan meletakkan kepentingan serta keselamatan Keluarga Malaysia lebih daripada segala-galanya. 4. Saya akui bahawa kita sedang berada dalam keadaan yang getir akibat pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi dan diburukkan lagi dengan ketidakstabilan politik negara. 5. Berdasarkan ramalan Pertubuhan Kesihatan Sedunia (WHO), kita akan hidup bersama COVID-19 sebagai endemik, yang bersifat kekal dan menjadi sebahagian daripada kehidupan manusia. 6. Dunia mencatatkan kemunculan Variant of Concern (VOC) yang lebih agresif dan rekod di seluruh dunia menunjukkan mereka yang telah divaksinasi masih boleh dijangkiti COVID- 19. 7. Oleh itu, kerajaan akan memperkasa Agenda Nasional Malaysia Sihat (ANMS) dalam mendidik Keluarga Malaysia untuk hidup bersama virus ini. Kita perlu terus mengawal segala risiko COVID-19 dan mengamalkan norma baharu dalam kehidupan seharian. -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

5 April 2014 MH370 PRESS BRIEFING by HISHAMMUDDIN HUSSEIN, MINISTER of DEFENCE and ACTING MINISTER of TRANSPORT 1. Introduction

5 April 2014 MH370 PRESS BRIEFING BY HISHAMMUDDIN HUSSEIN, MINISTER OF DEFENCE AND ACTING MINISTER OF TRANSPORT 1. Introduction It’s been almost a month since MH370 went missing. The search operation has been difficult, challenging and complex. In spite of all this, our determination remains undiminished. We will continue the search with the same level of vigour and intensity. We owe this to the families of those on board, and to the wider world. We will continue to focus, with all our efforts, on finding the aircraft. 2. Investigation into MH370 As per the requirements set out by the ICAO in Annex 13 of the International Standards and Recommended Practices, Malaysia will continue to lead the investigation into MH370. As per the ICAO standards, Malaysia will also appoint an independent ‘Investigator In Charge’ to lead an investigation team. The investigation team will include three groups: an airworthiness group, to look at issues such as maintenance records, structures and systems; an operations group, to examine things such as flight recorders, operations and meteorology; and a medical and human factors group, to investigate issues such as psychology, pathology and survival factors. The investigation team will also include accredited countries. Malaysia has already asked Australia to be accredited to the investigation team, and they have accepted. We will also include China, the United States, the United Kingdom and France as accredited representatives to the investigation team, along with other countries that we feel are in a position to help. 3. Formation of committees In addition to the new investigation team mentioned above, the Government - in order to streamline and strengthen our on-going efforts - has established three ministerial committees. -

How the Pandemic Is Keeping Malaysia's Politics Messy

How the Pandemic Is Keeping Malaysia’s Politics Messy Malaysia’s first transfer of power in six decades was hailed as a milestone for transparency, free speech and racial tolerance in the multiethnic Southeast Asian country. But the new coalition collapsed amid an all-too-familiar mix of political intrigue and horse trading. Elements of the old regime were brought into a new government that also proved short-lived. The turmoil stems in part from an entrenched system of affirmative-action policies that critics say fosters cronyism and identity-based politics, while a state of emergency declared due to the coronavirus pandemic has hampered plans for fresh elections. 1. How did this start? Two veteran politicians, Mahathir Mohamad and Anwar Ibrahim, won a surprising election victory in 2018 that ousted then-Prime Minister Najib Razak, who was enmeshed in a massive money-laundering scandal linked to the state investment firm 1MDB. Mahathir, 96, became prime minister again (he had held the post from 1981 to 2003), with the understanding that he would hand over to Anwar at some point. Delays in setting a date and policy disputes led to tensions that boiled over in 2020. Mahathir stepped down and sought to strengthen his hand by forming a unity government outside party politics. But the king pre-empted his efforts by naming Mahathir’s erstwhile right-hand man, Muhyiddin Yassin, as prime minister, the eighth since Malaysia’s independence from the U.K. in 1957. Mahathir formed a new party to take on the government but failed to get it registered.